Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8301

Revised: July 11, 2013

Accepted: July 18, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

Processing time: 209 Days and 10.9 Hours

AIM: To explore associations between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and benign gastrointestinal and pancreato-biliary disorders.

METHODS: Patient demographics, diagnoses, and hospital outcomes from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample were analyzed. Chronic liver diseases were identified using International Classification of Diseases, the 9th Revision, Clinical Modification codes. Patients with NAFLD were compared to those with other chronic liver diseases for the endpoints of total hospital charges, disease severity, and hospital mortality. Multivariable stepwise logistic regression analyses to assess for the independent association of demographic, comorbidity, and diagnosis variables with the event of NAFLD (vs other chronic liver diseases) were also performed.

RESULTS: Of 7800441 discharge records, 32347 (0.4%) and 271049 (3.5%) included diagnoses of NAFLD and other chronic liver diseases, respectively. NAFLD patients were younger (average 52.3 years vs 55.3 years), more often female (58.8% vs 41.6%), less often black (9.6% vs 18.6%), and were from higher income areas (23.7% vs 17.7%) compared to counterparts with other chronic liver diseases (all P < 0.0001). Diabetes mellitus (43.4% vs 28.9%), hypertension (56.9% vs 47.6%), morbid obesity (36.9% vs 8.0%), dyslipidemia (37.9% vs 15.6%), and the metabolic syndrome (28.75% vs 8.8%) were all more common among NAFLD patients (all P < 0.0001). The average total hospital charge ($39607 vs $51665), disease severity scores, and intra-hospital mortality (0.9% vs 6.0%) were lower among NALFD patients compared to those with other chronic liver diseases (all P < 0.0001).Compared with other chronic liver diseases, NAFLD was significantly associated with diverticular disorders [OR = 4.26 (3.89-4.67)], inflammatory bowel diseases [OR = 3.64 (3.10-4.28)], gallstone related diseases [OR = 3.59 (3.40-3.79)], and benign pancreatitis [OR = 2.95 (2.79-3.12)] on multivariable logistic regression (all P < 0.0001) when the latter disorders were the principal diagnoses on hospital discharge. Similar relationships were observed when the latter disorders were associated diagnoses on hospital discharge.

CONCLUSION: NAFLD is associated with diverticular, inflammatory bowel, gallstone, and benign pancreatitis disorders. Compared with other liver diseases, patients with NAFLD have lower hospital charges and mortality.

Core tip: This study analyzed the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample to compare outcomes and associations between patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and other chronic liver diseases. Compared with other liver diseases, NAFLD is associated with diverticular, inflammatory bowel, gallstone, and benign pancreatitis disorders when these latter disorders are considered as either the principal or associated diagnoses on discharge. These associations suggest shared mechanisms of pathology between NAFLD and these benign gastrointestinal disorders. Furthermore, patients with NAFLD have lower hospital mortality and consume fewer healthcare resources compared to patients with other chronic liver diseases.

- Citation: Reddy SK, Zhan M, Alexander HR, El-Kamary SS. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with benign gastrointestinal disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8301-8311

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8301.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8301

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the United States[1].Outpatient primary care and specialist cohort series report prevalence proportions of 25%-46%[2-4]. Yet the proportion of hospitalized patients diagnosed with NAFLD is unknown. The prevalence of NAFLD in hospitalized patients maybe similar to outpatient cohorts given the associations between NAFLD and disorders common among hospitalized patients--including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, venous thromboembolism, colorectal cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease[5-13]. Conversely, NAFLD may comprise a small percentage of chronic liver disease among hospitalized patients because hepatic complications (such as ascites, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular carcinoma) are less common with NAFLD compared to hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and alcohol associated liver diseases[10,14-19]. Finally, it is unclear if NAFLD is widely recognized by health care providers. This knowledge gap is important given recent small, single institutional studies suggesting relationships between NAFLD and benign digestive and pancreato-biliary disorders including diverticular disease, gallstone disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease[20-23]. Recognition of associations between NAFLD and these conditions may reveal insights into the pathologic mechanisms of all disorders.

The objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of the diagnosis of NAFLD among hospitalized patients in the United States and to explore associations between NAFLD and benign gastrointestinal and pancreato-biliary disorders.

Data were abstracted from the 2010 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The 2010 NIS contains discharge information from 1051 non-Federal, short-term, general, and specialty hospitals located in 45 states; approximating a 20% stratified sample of United States community hospitals[24]. This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

This study comprised patients with a diagnosis of chronic liver disease and compared patients with NAFLD vs any other chronic liver disease. All 25 diagnoses listed in each record were searched in creating each subsample in this study. The International Classification of Diseases, the 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code of 571.8 (“other chronic nonalcoholic liver disease”) was used to identify the NAFLD subsample. The “other chronic liver disease” subsample was identified using diagnosis codes describing other recognized etiologies of chronic liver disease, chronic liver disease of unknown etiology, and viral infections and errors in mineral metabolism which may lead to chronic liver disease (Table 1). Patient discharge records with diagnoses representing other liver diseases were eliminated from the NAFLD subsample. To eliminate records with possible alcoholic liver disease from the NAFLD subsample, records which included diagnoses pertaining to ethanol abuse, dependence, and/or overdose (Table 1) were removed from the NAFLD subsample. Similarly, records with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code of 571.8 were eliminated from the “other chronic liver disease”subsample. Nationwide prevalence estimates were calculated using both unweighted and discharge weights, which account for the number of calendar quarters for which each hospital contributed discharges to the NIS[24,25].

| ICD-9-CM diagnosis | Diagnosis | |

| The “other liver disease” cohort | 571 | Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis |

| 571 | Alcoholic fatty liver | |

| 571.1 | Acute alcoholic hepatitis | |

| 571.2 | Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver | |

| 571.3 | Alcoholic liver damage, unspecified | |

| 571.4 | Chronic hepatitis | |

| 571.4 | Chronic hepatitis unspecified | |

| 571.41 | Chronic persistent hepatitis | |

| 571.42 | Autoimmune hepatitis | |

| 571.49 | Other chronic hepatitis | |

| 571.5 | Cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol | |

| 571.6 | Biliary cirrhosis | |

| 571.9 | Other unspecified chronic liver disease without mention of alcohol | |

| 573 | Other disorders of liver | |

| 573.1 | Hepatitis in viral diseases classified elsewhere | |

| 573.2 | Hepatitis in other infectious diseases classified elsewhere | |

| 573.3 | Hepatitis, unspecified | |

| 573.8 | Other specified disorders of liver | |

| 573.9 | Unspecified disorder of liver | |

| 70 | Viral hepatitis | |

| 70 | Viral hepatitis A with hepatic coma | |

| 70.1 | Viral hepatitis A without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.2 | Viral hepatitis B with hepatic coma | |

| 70.2 | Viral hepatitis B with hepatic coma, acute or unspecified without hepatitis delta | |

| 70.21 | Viral hepatitis B with hepatic coma, acute or unspecified with hepatitis delta | |

| 70.22 | Chronic viral hepatitis B with hepatic coma without hepatitis delta | |

| 70.23 | Chronic viral hepatitis B with hepatic coma with hepatitis delta | |

| 70.3 | Viral hepatitis b without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.3 | Viral hepatitis B without mention of hepatic coma, acute or unspecified, without mention of hepatitis delta | |

| 70.31 | Viral hepatitis B without mention of hepatic coma, acute or unspecified, with hepatitis delta | |

| 70.32 | Chronic viral hepatitis B without mention of hepatic coma without mention of hepatitis delta | |

| 70.33 | Chronic viral hepatitis B without mention of hepatic coma with hepatitis delta | |

| 70.4 | Other specified viral hepatitis with hepatic coma | |

| 70.41 | Acute hepatitis C with hepatic coma | |

| 70.42 | Hepatitis delta without mention of active hepatitis B disease with hepatic coma | |

| 70.43 | Hepatitis E with hepatic coma | |

| 70.44 | Chronic hepatitis C with hepatic coma | |

| 70.49 | Other specified viral hepatitis with hepatic coma | |

| 70.5 | Other specified viral hepatitis without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.51 | Acute hepatitis C without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.52 | Hepatitis delta without mention of active hepatitis B disease or hepatic coma | |

| 70.53 | Hepatitis E without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.54 | Chronic hepatitis C without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.59 | Other specified viral hepatitis without mention of hepatic coma | |

| 70.6 | Unspecified viral hepatitis with hepatic coma | |

| 70.7 | Unspecified viral hepatitis c | |

| 70.7 | Unspecified viral hepatitis C without hepatic coma | |

| 70.71 | Unspecified viral hepatitis C with hepatic coma | |

| 70.9 | Unspecified viral hepatitis without mention of hepatic coma | |

| V02.6 | Carrier or suspected carrier of viral hepatitis | |

| V02.60 | Viral hepatitis carrier, unspecified | |

| V02.61 | Hepatitis B carrier | |

| V02.62 | Hepatitis C carrier | |

| V02.69 | Other viral hepatitis carrier | |

| 275 | Disorders of iron metabolism | |

| 275.01 | Hereditary hemochromatosis | |

| 275.02 | Hemochromatosis due to repeated red blood cell transfusions | |

| 275.03 | Other hemochromatosis | |

| 275.09 | Other disorders of iron metabolism | |

| 275.1 | Disorders of copper metabolism | |

| Alcohol abuse, dependence, and/or overdose | 291 | Alcohol-induced mental disorders |

| 291 | Alcohol withdrawal delirium | |

| 291.1 | Alcohol-induced persisting amnestic disorder | |

| 291.2 | Alcohol-induced persisting dementia | |

| 291.3 | Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations | |

| 291.4 | Idiosyncratic alcohol intoxication | |

| 291.5 | Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions | |

| 291.8 | Other specified alcohol-induced mental disorders | |

| 291.81 | Alcohol withdrawal | |

| 291.82 | Alcohol-induced sleep disorder | |

| 291.89 | Other alcoholic psychosis | |

| 291.9 | Unspecified alcohol-induced mental disorders | |

| 303 | Alcohol dependence syndrome | |

| 303 | Acute alcoholic intoxication | |

| 303 | Acute alcoholic intoxication in alcoholism unspecified drinking behavior | |

| 303.01 | Acute alcoholic intoxication in alcoholism continuous drinking behavior | |

| 303.02 | Acute alcoholic intoxication in alcoholism episodic drinking behavior | |

| 303.03 | Acute alcoholic intoxication in alcoholism in remission | |

| 303.9 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence | |

| 303.9 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence unspecified drinking behavior | |

| 303.91 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence continuous drinking behavior | |

| 303.92 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence episodic drinking behavior | |

| 303.93 | Other and unspecified alcohol dependence in remission |

The location of patient’s residence included central counties of greater than one million population, fringe counties of metropolitan areas of greater than one million population, counties in metropolitan areas of 250000-999999 population, counties in metropolitan areas of 50000-249999 population, and micropolitan counties in areas of less than 50000 population. The reported median income is the median income for the population in the zip code from which the patient pertaining to that particular discharge record resides[25].

All diagnoses were searched to determine the presence of obesity (ICD-9-CM codes 278, 278.0, 278.00, 278.01, 278.02, or 278.03) and dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272, 272.0, 272.1, 272.2, 272.3, 272.4, 272.5, 272.8, or 272.9). The presence of associated diagnoses (principal or secondary) were determined using the clinical classification software provided by the AHRQ[26] (Table 2). Criteria for the metabolic syndrome include the presence of any three of obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia[27,28]. Principal discharge diagnoses were also identified by the Disease Staging© (Thomson Reuters) classification system[29] (Table 3). The all patient refined diagnosis related group (APR-DRG© 3M) assesses severity of illness and mortality risk of the DRG pertaining to each patient discharge record[30].

| CCS Category | Diagnosis |

| 98 and 99 | Hypertension |

| 49 and 50 | Diabetes mellitus |

| 138 | Esophageal disorders (excluding ICD-9-CM diagnoses f.or varices) |

| 139 | Gastroduodenal ulcer |

| 140 | Gastritis and/or duodenitis |

| 141 | Other disorders of stomach and duodenum |

| 142 | Appendicitis |

| 143 | Abdmoninal and groin hernia |

| 144 | Inflammatory bowel diseases |

| 145 | Intestinal obstruction |

| 146 | Diverticular disease |

| 147 | Anal and rectal conditions |

| 148 | Peritonitis and intestinal abscess |

| 149 | Benign biliary tract disease |

| 152 | Benign pancreatic disorders excluding diabetes mellitus |

| 153 | Gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| 154 | Noninfectious gastroenteritis |

| Discharge category | Description |

| GIS03, GIS04, GIS18 | Benign anal-rectal disorders |

| GIS05 | Appendicitis |

| GIS09 or GIS37 | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| GIS10 | Diverticular disease |

| GIS17 or GIS84 | Gastroduodenitis |

| GIS19 | Hernia |

| GIS20 | Esophagitis |

| GIS25-30, HEP11, GIS82-83 | Upper gastrointestinal cancers |

| GIS31 | Gastroduodenal ulcer |

| HEP01 or HEP 84 | Gallstone related disorders |

| HEP12 or HEP85 | Non-malignant pancreatitis |

| HEP81 or HEP82 | Hepatobiliary malignancies |

Discrete and continuous variables were compared using χ2 and Student’s t tests with two-sided P values. Multivariable stepwise logistic regression analyses to assess for the independent association of each variable with the event of NAFLD were performed. The P value for variable entry and stay was 0.05. OR point estimates with 95% Wald confidence limits are reported. Results for those variables that did not stay in each model were not reported. Two multivariable analyses were performed-one using associated diagnoses and another using principal diagnoses. SAS© Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, United States) was used to perform all analyses.

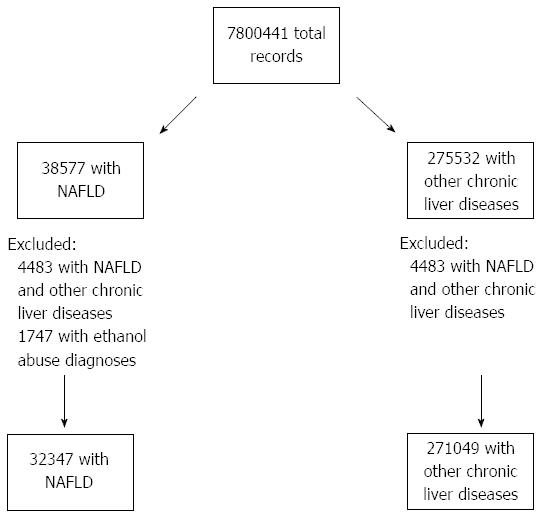

Of the 7800441 discharge records in the 2010 NIS, 314109 (4.0%) included a diagnosis describing any chronic liver disease (Figure 1). After excluding patients with diagnoses describing ethanol abuse, dependence, and/or overdose and those with other chronic liver diseases in addition to NAFLD, 32347 (0.4%) records contained the NAFLD diagnosis. Similarly, 271049 (3.5%) records included diagnosis codes describing other chronic liver diseasesand did not include NAFLD. When using discharge weighted analyses, 3.9% of all discharge records included a principal or secondary diagnosis describing any chronic liver disease. 0.4% and 3.4% records included diagnoses describing NAFLD and other chronic liver diseases excluding NAFLD, respectively.

NAFLD patients were younger, more often female, and less often black compared to counterparts with other chronic liver diseases (Table 4). Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia were all more common among NAFLD patients. Nearly 29% of the patients in the NAFLD subsample had the metabolic syndrome. NAFLD patients were from higher income areas and more often had private health insurance. The average total hospital charge and length of hospital stay were significantly shorter than among patients with other chronic liver diseases. Rates of NAFLD intra-hospital mortality and advanced APRDRG mortality and disease severity scores were all significantly lower than among patients with other chronic liver diseases.

| NAFLD (n = 32347) | Other liver diseases (n = 271049) | P value | Missing | |

| Average age (yr) | 52.3 ± 16.5 | 55.3 ± 15.4 | < 0.0001 | 0 |

| Female gender | 19027 (58.8) | 112788 (41.6) | < 0.0001 | 78 (0.0003) |

| Non-elective admission | 25291 (78.4) | 231024 (85.4) | < 0.0001 | 521 (0.2) |

| Ethnicity | < 0.0001 | 29349 (9.7) | ||

| White | 20536 (70.7) | 152778 (62.4) | ||

| Black | 2798 (9.6) | 45634 (18.6) | ||

| Hispanic | 4135 (14.2) | 32124 (13.1) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 592 (2.0) | 5720 (2.3) | ||

| Native American | 191 (0.7) | 2075 (0.9) | ||

| Other | 797 (2.7) | 6667 (2.7) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 14027 (43.4) | 78011 (28.9) | < 0.0001 | |

| Hypertension | 18413 (56.9) | 129031 (47.6) | < 0.0001 | |

| Obesity | 11920 (36.9) | 21677 (8.0) | < 0.0001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 12262 (37.9) | 42299 (15.6) | < 0.0001 | |

| Metabolic syndrome | 9286 (28.7) | 23888 (8.8) | < 0.0001 | |

| Location | < 0.0001 | 13512 (4.4) | ||

| Central Metropolitan | 9115 (28.8) | 91426 (35.4) | ||

| Fringe Metropolitan | 8540 (27.0) | 58794 (22.8) | ||

| Metro below one million | 6003 (19.0) | 48308 (18.7) | ||

| 50000-250000 population | 2563 (8.1) | 19519 (7.6) | ||

| Micropolitan | 3482 (11.0) | 24641 (9.5) | ||

| Other | 1948 (6.2) | 15545 (6.0) | ||

| Median zip code income ($) | < 0.0001 | 13104 (4.3) | ||

| < 39000 | 8003 (25.3) | 89265 (34.5) | ||

| 39000-47999 | 8140 (25.7) | 65082 (25.2) | ||

| 48000-62999 | 8006 (25.3) | 58595 (22.7) | ||

| ≥ 63000 | 7488 (23.7) | 45713 (17.7) | ||

| Primary payer | < 0.0001 | 870 (0.3) | ||

| Medicare | 10429 (32.3) | 104892 (38.8) | ||

| Medicaid | 4461 (13.8) | 65829 (24.4) | ||

| Private | 13602 (42.1) | 59410 (22.0) | ||

| Self-pay | 2454 (7.6) | 24729 (9.2) | ||

| No charge | 244 (0.8) | 2917 (1.1) | ||

| Other | 1107 (3.4) | 12452 (4.6) | ||

| Major operative procedure | 9804 (30.3) | 47187 (17.4) | < 0.0001 | 0 |

| Average total hospital charges ($) | 39607.3 ± 52512 | 51665 ± 90685 | < 0.0001 | 0 |

| Average length of hospital stay (d) | 4.7 ± 6.0 | 6.6 ± 9.7 | < 0.0001 | 0 |

| Discharge disposition | < 0.0001 | 420 (0.001) | ||

| Routine | 25703 (79.5) | 167545 (61.9) | ||

| Acute care | 660 (2.0) | 9190 (3.4) | ||

| Another health facility | 2273 (7.0) | 39311 (14.5) | ||

| Home Health | 3114 (9.6) | 30276 (11.2) | ||

| AMA | 269 (0.8) | 7691 (2.8) | ||

| Other | 10 (0.03) | 479 (0.2) | ||

| Died in hospital | 301 (0.9) | 16154 (6.0) | < 0.0001 | 571 (0.2) |

| Aprdrg mortality risk | < 0.0001 | 347 (0.1) | ||

| Minor | 14347 (44.4) | 82849 (30.4) | ||

| Moderate | 11678 (36.1) | 84343 (31.1) | ||

| Major | 4921 (15.2) | 63614 (23.5) | ||

| Extreme | 1377 (4.3) | 40280 (14.9) | ||

| Aprdrg severity | < 0.0001 | 347 (0.1) | ||

| Minor functional loss | 814 (2.5) | 12242 (4.5) | ||

| Moderate functional loss | 18105 (56.0) | 88446 (32.6) | ||

| Major functional loss | 11156 (35.0) | 116365 (43.0) | ||

| Extreme functional loss | 2248 (7.0) | 53673 (19.8) | ||

| Associated Diagnoses | ||||

| Abdominal Hernia | 3459 (10.7) | 12755 (4.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Appendiceal disorders | 254 (0.8) | 728 (0.3) | < 0.0001 | |

| Benign anus-rectum disorders | 174 (0.5) | 1401 (0.5) | 0.62 | |

| Benign biliary disorders | 5421 (16.8) | 19306 (7.1) | < 0.0001 | |

| Benign pancreatic disorders | 3379 (10.5) | 15898 (5.9) | < 0.0001 | |

| Diverticular disease | 2845 (8.8) | 8697 (3.2) | < 0.0001 | |

| Esophageal disorders (non-variceal) | 9114 (28.2) | 41835 (15.4) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastritis/duodenitis | 2163 (6.7) | 11220 (4.1) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | 1011 (3.1) | 7477 (2.8) | 0.002 | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1119 (3.5) | 23651 (8.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastrointestinal malignancies | 688 (2.1) | 6871 (2.5) | < 0.0001 | |

| Hepatobiliary malignancies | 84 (0.3) | 7903 (2.9) | < 0.0001 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 555 (1.7) | 2659 (1.0) | < 0.0001 | |

| Intestinal infection | 886 (2.7) | 5904 (2.2) | < 0.0001 | |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1346 (4.2) | 7898 (2.9) | < 0.0001 | |

| Peritonitis-abscess | 326 (1.0) | 5772 (2.1) | < 0.0001 | |

| Principal discharge diagnoses | ||||

| Appendicitis | 217 (0.7) | 554 (0.2) | < 0.0001 | |

| Benign anus-rectal disorders | 163 (0.5) | 1694 (0.6) | 0.008 | |

| Benign pancreatitis | 2224 (6.9) | 7074 (2.6) | < 0.0001 | |

| Diverticular disease | 898 (2.8) | 1805 (0.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Esophagitis | 306 (1.0) | 1762 (0.7) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gallstone disorders | 2622 (8.1) | 5978 (2.2) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | 232 (0.7) | 2572 (1.0) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastroduodenitis | 713 (2.2) | 3481 (1.3) | < 0.0001 | |

| Gastrointestinal malignancies | 338 (1.0) | 3017 (1.1) | 0.27 | |

| Hepatobiliary malignancies | 68 (0.2) | 2837 (1.1) | < 0.0001 | |

| Hernia | 204 (0.6) | 1497 (0.6) | 0.07 | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 242 (0.8) | 696 (0.3) | < 0.0001 | |

| Intestinal Infection | 235 (0.7) | 1999 (0.7) | 0.83 |

As a principal or secondary (e.g., associated) diagnoses, abdominal hernia, appendiceal disorders, benign biliary and pancreatic disorders, diverticular disease, non-variceal esophageal disorders, gastritis/duodenitits, gastroduodenal ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease, and intestinal infection were all significantly more common among NAFLD patients (Table 5). Conversely, gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary malignancies, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, and peritonitis/intra-abdominal abscess were all more common among patients with other chronic liver diseases. NAFLD patients were more likely to have a principal diagnosis on discharge of appendicitis, benign pancreatitis, diverticular disease, esophagitis, gallstone disorders, gastroduodenitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. In contrast, benign ano-rectal disorders, gastroduodenal ulcers, and hepatobiliary cancers were more common among patients with other chronic liver diseases.

| Variable | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age (reference ≤ 70 yr) | < 0.0001 | 0.79 (0.76-0.83) |

| Gender (reference female) | < 0.0001 | 0.58 (0.57-0.60) |

| Diabetes | < 0.0001 | 1.41 (1.37-1.45) |

| Hypertension | 0.05 | 0.97 (0.94-1.0) |

| Obesity | < 0.0001 | 4.47 (4.34-4.61) |

| Dyslipidemia | < 0.0001 | 2.35 (2.28-2.42) |

| Location (reference central metropolitan) | < 0.0001 | |

| 50000-250000 population | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | |

| Fringe metropolitan | 1.1 (1.1-1.2) | |

| Metro 250000 - one million population | 1.2 (1.1-1.2) | |

| Micropolitan | 1.4 (1.4-1.5) | |

| Other | 1.4 (1.3-1.4) | |

| Income (reference ≥ $63000) | < 0.0001 | |

| $39000-$47999 | 0.80 (0.77-0.83) | |

| $48000-$62999 | 0.86 (0.82-0.89) | |

| < $39000 | 0.64 (0.62-0.67) | |

| Payer (reference private insurance) | < 0.0001 | |

| Medicaid | 0.42 (0.41-0.43) | |

| Medicare | 0.46 (0.44-0.47) | |

| No charge | 0.61 (0.53-0.70) | |

| Other | 0.55 (0.51-0.59) | |

| Self-pay | 0.65 (0.62-0.68) | |

| Associated diagnoses | ||

| Abdominal hernia | < 0.0001 | 1.70 (1.63-1.79) |

| Appendiceal disorders | < 0.0001 | 2.58 (2.19-3.04) |

| Benign biliary disorders | < 0.0001 | 2.11 (2.03-2.19) |

| Benign pancreatic disorders | < 0.0001 | 1.57 (1.50-1.64) |

| Diverticular disease | < 0.0001 | 2.22 (2.11-2.34) |

| Esophageal disorders (non-variceal) | < 0.0001 | 1.52 (1.48-1.57) |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | < 0.0001 | 1.41(1.33-1.49) |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | < 0.0001 | 0.41 (0.38-0.44) |

| Gastrointestinal malignancies | < 0.0001 | 0.83 (0.76-0.91) |

| Hepatobiliary malignancies | < 0.0001 | 0.12 (0.10-0.15) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | < 0.0001 | 1.68 (1.52-1.86) |

| Intestinal infection | < 0.0001 | 1.29 (1.19-1.40) |

| Intestinal obstruction | < 0.0001 | 1.30 (1.22-1.39) |

| Peritonitis-abscess | < 0.0001 | 0.47 (0.42-0.53) |

All variables with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) on univariable analysis (Table 4) were included in multivariable logistic regression models. When considering each gastrointestinal, hepatic, or pancreato-biliary diagnosis as an associated diagnosis, the patterns of association observed on univariable comparisons were maintained on multivariable logistic regression (Table 5). When considering each disorder as the principal diagnosis, appendicitis, benign pancreatitis, diverticular disease, esophagitis, gallstone disorders, Gastroduodenitis, and hernia were all associated with NAFLD on multivariable logistic regression (Table 6). Hepatobiliary cancers were independently associated with other liver diseases. In both analyses, female gender, younger patient age, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia, higher income, and private health insurance were independently associated with NAFLD.

| Variable | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Age (reference ≤ 70 yr) | < 0.0001 | 0.84 (0.81-0.88) |

| Gender (reference female) | < 0.0001 | 0.55 (0.53-0.56) |

| Diabetes | < 0.0001 | 1.38 (1.35-1.42) |

| Obesity | < 0.0001 | 4.75 (4.61-4.89) |

| Dyslipidemia | < 0.0001 | 2.51 (2.44-2.58) |

| Location (reference central metropolitan) | < 0.0001 | |

| 50000-250000 population | 1.21 (1.14-1.27) | |

| Fringe metropolitan | 1.12 (1.09-1.17) | |

| Metro 250000 - one million population | 1.15 (1.11-1.20) | |

| Micropolitan | 1.44 (1.37-1.51) | |

| Other | 1.37 (1.29-1.45) | |

| Income (reference > $63000) | < 0.0001 | |

| $39000-$47999 | 0.80 (0.77-0.83) | |

| $48000-$63000 | 0.86 (0.83-0.89) | |

| < $39000 | 0.64 (0.62-0.67) | |

| Payer (reference private insurance) | < 0.0001 | |

| Medicaid | 0.42 (0.40-0.43) | |

| Medicare | 0.47 (0.46-0.49) | |

| No charge | 0.60 (0.52-0.69) | |

| Other | 0.54 (0.50-0.58) | |

| Self-pay | 0.62(0.59-0.65) | |

| Principal discharge diagnosis | ||

| Appendicitis | < 0.0001 | 3.53 (2.96-4.22) |

| Benign pancreatitis | < 0.0001 | 2.95 (2.79-3.12) |

| Diverticular disease | < 0.0001 | 4.26 (3.89-4.67) |

| Esophagitis | < 0.0001 | 1.69 (1.48-1.93) |

| Gallstone disorders | < 0.0001 | 3.59 (3.40-3.79) |

| Gastroduodenitis | < 0.0001 | 2.09 (1.91-2.29) |

| Hepatobiliary malignancies | < 0.0001 | 0.29 (0.22-0.37) |

| Hernia | 0.01 | 1.23 (1.04-1.45) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | < 0.0001 | 3.64 (3.10-4.28) |

We performed subgroup analyses of records with a principal discharge diagnosis of diverticular disease, gallstone related disordersor benign pancreatitis. We chose these disorders because of their high prevalence in our sample. When stratified by type of background liver disease, similar differences in ethnicity, gender, comorbidities, health insurance payer, age, hospital charges, and income existed for each subgroupas in the overall sample (Table 7). As in the overall sample, total hospital charges, length of hospital stay, discharge disposition, rates of hospital death and APRDRG mortality and disease severity scores were all greater among patients with other chronic liver diseases in each subgroup.

| Diverticular disease (n = 2703) | Gallstone disease (n = 8600) | Benign pancreatitis (n = 9298) | |||||||

| NAFLD (n = 898) | OLD (n = 1805) | P value | NAFLD (n = 2622) | OLD (n = 5978) | P value | NAFLD (n = 2224) | OLD (n = 7074) | P value | |

| Average age (yr) | 55.1 ± 13.5 | 62.7 ± 14.2 | < 0.0001 | 50.5 ± 16.7 | 57.7 ± 17.4 | < 0.0001 | 47.8 ± 15.5 | 51.9 ± 14.0 | < 0.0001 |

| Female Gender | 501 (55.8) | 897 (49.7) | < 0.003 | 1606 (61.3) | 3056 (51.2) | < 0.0001 | 1058 (47.6) | 2796 (39.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Non-elective admission | 791 (88.3) | 1612 (89.5) | 0.36 | 2305 (88.4) | 5137 (86.0) | < 0.0001 | 2110 (95.1) | 6680 (94.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Ethnicity | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| White | 610 (74.5) | 1174 (72.1) | 1575 (65.3) | 3532 (65.5) | 1376 (67.8) | 3910 (60.8) | |||

| Black | 48 (5.9) | 236 (14.5) | 166 (6.9) | 633 (11.7) | 196 (9.7) | 1355 (21.1) | |||

| Hispanic | 128 (15.7) | 159 (9.8) | 519 (21.5%) | 882 (16.4) | 339 (16.7) | 854 (13.3) | |||

| Other | 33 (4.0) | 60 (3.7) | 152 (6.3) | 344 (6.4) | 119 (5.9) | 313 (4.9) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 276 (30.7) | 440 (24.4) | 0.0004 | 816 (31.1) | 1603 (26.8) | < 0.0001 | 984 (44.2) | 1974 (27.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 490 (54.6) | 1021 (56.6) | 0.32 | 1285 (49.0) | 2892 (48.4) | < 0.0001 | 1222 (55.0) | 3524 (49.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Obesity | 252 (28.1) | 200 (11.1) | < 0.0001 | 1010 (38.5) | 770 (12.9) | < 0.0001 | 680 (30.6) | 561 (7.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 319 (35.5) | 451 (25.0) | < 0.0001 | 818 (31.2) | 1233 (20.6) | < 0.0001 | 1093 (49.2) | 1359 (19.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 178 (19.8) | 195 (10.8) | < 0.0001 | 567 (21.6) | 638 (10.7) | < 0.0001 | 662 (29.8) | 721 (10.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Location | 0.02 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Central Metro | 268 (30.6) | 537 (30.7) | 835 (32.5) | 1775 (30.7) | 603 (27.8) | 2184 (32.6) | |||

| Fringe Metro | 247 (28.2) | 436 (24.9) | 707 (27.5) | 1379 (23.9) | 600 (27.6) | 1554 (23.2) | |||

| Metro below one million | 185 (21.1) | 322 (18.4) | 505(19.7) | 1132 (19.6) | 406 (18.7) | 1373 (20.5) | |||

| 50000-250000 | 53 (6.1) | 147 (8.4) | 160 (6.2) | 427 (7.4) | 185 (8.5) | 536 (8.0) | |||

| Micropolitan | 81 (9.3) | 187 (10.7) | 237 (9.2) | 651 (11.3) | 238 (11.0) | 626 (9.3) | |||

| Other | 42 (4.8) | 119 (6.8) | 124 (4.8) | 411 (7.1) | 140 (6.5) | 437 (6.5) | |||

| Median zip code income ($) | 0.0008 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| < 39000 | 202 (22.8) | 502 (28.5) | 632 (24.6) | 166 (28.9) | 556 (25.6) | 2334 (34.4) | |||

| 39000-47999 | 209 (23.5) | 437 (24.8) | 640 (24.9) | 1550 (26.9) | 534 (24.6) | 1734 (25.5) | |||

| 48000-63000 | 233 (26.2) | 445 (25.2) | 676 (26.3) | 1446 (25.1) | 564 (25.9) | 1527 (22.5) | |||

| > 63000 | 244 (27.5) | 380 (21.5) | 618 (24.1) | 1107 (19.2) | 520 (23.9) | 1196 (17.6) | |||

| Primary payer | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Medicare | 256 (28.5) | 866 (48.1) | 659 (25.2) | 2461 (41.2) | 523 (23.6) | 2028 (28.8) | |||

| Medicaid | 60 (6.7) | 181 (10.1) | 382 (14.6) | 1016 (17.0) | 320 (14.4) | 1682 (23.9) | |||

| Private | 469 (52.2) | 562 (31.2) | 1229 (46.9) | 1687 (28.3) | 971 (43.7) | 1742 (24.7) | |||

| Self-pay | 75 (8.4) | 119 (6.6) | 215 (8.2) | 531 (8.9) | 295 (13.3) | 1054 (15.0) | |||

| No charge | 6 (0.7) | 15 (0.8) | 27 (1.0) | 53 (0.9) | 24 (1.1) | 128 (1.8) | |||

| Other | 32 (3.6) | 58 (3.2) | 106 (4.1) | 219 (3.7) | 87 (3.9) | 418 (5.9) | |||

| Major operative procedure | 109 (12.1) | 333 (18.5) | < 0.0001 | 2002 (76.4) | 3327 (55.7) | < 0.0001 | 294 (13.2) | 652 (9.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Average total hospital charges ($) | 26868.7 ± 26364.6 | 46666.9 ± 80222.8 | < 0.0001 | 40016.5 ± 32898.6 | 49682.8 ± 65425.9 | < 0.0001 | 32680.5 ± 42691.0 | 45115.5 ± 83193.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Average length of hospital stay (d) | 4.2 ± 3.4 | 6.0 ± 8.3 | < 0.0001 | 4.0 ± 3.4 | 5.6 ± 6.1 | < 0.0001 | 4.9 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 8.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Discharge Disposition | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Routine | 821 (91.4) | 1355 (75.2) | 2403 (91.8) | 4492 (75.3) | 2013 (90.5) | 5396 (76.3) | |||

| Acute care | 2 (0.2) | 33 (1.8) | 32 (1.2) | 240 (4.0) | 45 (2.0) | 209 (3.0) | |||

| Another health facility | 25 (2.8) | 158 (8.8) | 66 (2.5) | 503 (8.4) | 47 (2.1) | 480 (6.8) | |||

| Home Health | 44 (4.9) | 184 (10.2) | 101 (3.9) | 487 (8.2) | 86 (3.9) | 361 (5.1) | |||

| AMA | 5 (0.6) | 17 (0.9) | 14 (0.5) | 81 (1.4) | 22 (1.0) | 325 (4.6) | |||

| Other | 0 | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 7 (0.1) | 0 | 4 (0.1) | |||

| Died in hospital | 1 (0.1) | 53 (2.9) | < 0.0001 | 3 (0.1) | 157 (2.6) | < 0.0001 | 11 (0.5) | 296 (4.2) | < 0.0001 |

| APRDRG Mortality risk | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Minor | 530 (59.0) | 783 (43.4) | 1457 (55.6) | 2123 (35.5) | 1177 (52.9) | 2658 (37.6) | |||

| Moderate | 278 (31.0) | 563 (31.2) | 936 (35.7) | 2095 (35.1) | 746 (33.5) | 2308 (32.6) | |||

| Major | 82 (9.1) | 291 (16.1) | 188 (7.2) | 1187 (19.9) | 238 (10.7) | 1318 (18.6) | |||

| Extreme | 8 (0.9) | 167 (9.3) | 37 (1.4) | 571 (9.6) | 61 (2.7) | 785 (11.1) | |||

| APRDRG Severity | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | ||||||

| Minor functional loss | 0 | 163 (9.0) | 1 (0.04%) | 377 (6.3) | 1 (0.04) | 347 (4.9) | |||

| Moderate functional loss | 645 (71.8) | 747 (41.4) | 1828 (69.7) | 2371 (39.7) | 1318 (59.3) | 2721 (38.5) | |||

| Major functional loss | 231 (25.7) | 697 (38.6) | 715 (27.3) | 2393 (40.0) | 791 (35.6) | 2855 (40.4) | |||

| Extreme functional loss | 22 | 197 (10.9) | 74 | 835 (14.0) | 112 (5.0) | 1146 (16.2) | |||

| -2.5 | -2.8 | ||||||||

The diagnosis of NAFLD among hospitalized patients is much less common compared to that noted in outpatient cohort studies[2-4]. Our findings that patients with NAFLD were more likely to be female, obese, and non-Black and more likely have diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome compared to patients with other chronic liver diseases is in agreement with other studies[10,14-19]-suggesting that our methods to identify these patients were accurate. Similarly, patients with other liver diseases were more frequently from low-income regions and less likely to have private insurance as the primary health care payer; reflecting the higher prevalence of hepatitis C viral infections and alcohol abuse in low-income areas. The discrepancy in prevalence of NAFLD in outpatient series compared with hospitalized patients shows that NAFLD is under-recognized in hospital patients and that the impact of NAFLD on clinical outcomes and health care resource utilizationis unrecognized.

NAFLD is associated with several benign gastrointestinal and pancreato-biliary disorders. The exceptions were gastrointestinal hemorrhage and peritonitis, which are expected to occur in patients with decompensated liver disease and thus are less likely in NAFLD patients compared to those with other chronic liver diseases[10,14-19]. Several studies have established the role of bacterial translocation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and severe steatosis[20,21,31-33]. This could be a potential mechanism for which diverticular disorders in particular are more commonly associated with NAFLD compared to other chronic liver diseases[21].Our finding of the association between NAFLD and gallstone disease is in agreement that a recent Italian study which noted a high prevalence of gallstone disease among patients with NAFLD[22]. Other series have noted similar findings[23,34].

Patients with NAFLD have better hospital outcomes, less severe disease severity and mortality risk, and utilize fewer health care resources compared to patients with other chronic liver diseases (Table 4). These relationships occurred despite the fact that more NAFLD patients underwent major operations, and were maintained in subgroup analysis of diverticular disease, gallstone disease, and benign pancreatitis (Table 7). Given that hepatic related morbidity more often occurs with other chronic liver diseases (such as hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease) compared to NAFLD[10,14-19], these findings suggest that the type and severity of background liver disease plays a vital role in determining overall patient outcomes and health care resource utilization.

There are several limitations to this study. It is unknown how background liver disease diagnoses were derived. Thus, the accuracy of NAFLD in this sample cannot be verified-especially when discharge abstracts used to construct this database were intended for reimbursement and not clinical research purposes. Similar problems regarding the accuracy of entered codes may exist when using ICD-9 diagnosis codes for elements of the metabolic syndrome, gastrointestinal disorders, and pancreato-biliary diseases. Distinctions between simple hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis, and degrees of fibrosis cannot be made in the NIS. Because medications were not included in the NIS, we were not able to account for drug induced fatty liver disease. This limitation has minimal influence on our conclusions since less than 2% of steatohepatitis is drug induced[9]. We attempted to homogenize the NAFLD subsample by using only one ICD-9-DM identifier and eliminating any records listing any other major potential etiology of background liver disease. We focused on patients with any diagnosis of chronic liver disease and postulated that these patients are the most likely to have undergone evaluation for NAFLD. NAFLD may coexist with other chronic liver diseases in a minority of patients[35-37]. It is therefore possible that we may have included patients with undiagnosed NAFLD in the “other liver disease”sample. The NIS is a discharge level database where each entry represents a hospital admission and not an individual patient-thus multiple readmissions for a single patient may have biased our results.

In conclusion, NAFLD is widely under diagnosed among hospitalized patients in the United States. NAFLD is associated with diverticular, gallstone, and benign pancreatic disorders. The type of background liver disease is a key factor in hospital outcomes and healthcare resource utilization among hospitalized patients.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease in the developed world. While prevalence proportions among outpatient series are well described, the proportion of hospitalized patients diagnosed with NAFLD is unknown. Moreover, associations of NAFLD to other gastrointestinal disorders are not well established.

The important research hotspots related to this article include (1) the prevalence of NAFLD diagnosis among hospitalized patients; (2) outcomes among hospitalized patients with NAFLD; and (3) relationships between NAFLD and other gastrointestinal disorders.

Most prior reports examining the prevalence of NAFLD are based on outpatient or cohort registry studies-data regarding the prevalence of NAFLD among hospitalized patients are sparse. Few studies have examined hospital outcomes among patients with NAFLD-most focus on long-term survival related to hepatic or cardiovascular complications. Previous studies looking at associations between NAFLD and other gastrointestinal disorders are small, single institution based, and often biased by patient selection and particular care settings. To overcome these obstacles, the authors used a large database that provides an accurate estimate of the prevalence of NALFD diagnosis among hospitalized patients across the United States. Analyses of these data show that patients with NAFLD have a lower frequency of hospital mortality and consume fewer healthcare resources compared to those with other chronic liver diseases. Finally, authors’ study demonstrates that NAFLD is associated with diverticular, inflammatory bowel, gallstone, and benign pancreatitis disorders independent of demographics or other comorbidities.

The study results suggest that suggest that the type of background liver disease plays a vital role in determining overall patient outcomes and health care resource utilization among hospitalized patients. The results also suggest shared mechanisms of disease pathology between NAFLD and diverticular, inflammatory bowel, gallstone, and benign pancreatitis disorders.

A principal diagnosis is the one diagnosis describing the main indication for admission and/or the condition which was the central focus of management during hospitalization. Associated diagnoses include the principal diagnosis, comorbid conditions, and disorders previously managed but not the focus of the particular hospitalization.

The authors mentioned the prevalence of NAFLD and the associations between NAFLD and other common gastrointestinal and pancreato-biliary disorders among hospitalized patients. The authors also discussed the impact of NAFLD on healthcare resource utilization.

P- Reviewer: Celikbilek M S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor:A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524-530.e1; quiz e60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 790] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, Harrison SA. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1522] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, Shaw JC, Cramb R, Olliff S, Gill PS, Neuberger JM, Lilford RJ, Newsome PN. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol. 2012;56:234-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387-1395. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Treeprasertsuk S, Leverage S, Adams LA, Lindor KD, St Sauver J, Angulo P. The Framingham risk score and heart disease in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2012;32:945-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bhatia LS, Curzen NP, Calder PC, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1190-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Di Minno MN, Tufano A, Rusolillo A, Di Minno G, Tarantino G. High prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver in patients with idiopathic venous thromboembolism. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6119-6122. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Muhidin SO, Magan AA, Osman KA, Syed S, Ahmed MH. The relationship between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and colorectal cancer: the future challenges and outcomes of the metabolic syndrome. J Obes. 2012;2012:637538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Larrain S, Rinella ME. A myriad of pathways to NASH. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:525-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Eguchi Y, Hyogo H, Ono M, Mizuta T, Ono N, Fujimoto K, Chayama K, Saibara T. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:586-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:460-468. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Leite NC, Villela-Nogueira CA, Pannain VL, Bottino AC, Rezende GF, Cardoso CR, Salles GF. Histopathological stages of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes: prevalences and correlated factors. Liver Int. 2011;31:700-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loomba R, Abraham M, Unalp A, Wilson L, Lavine J, Doo E, Bass NM. Association between diabetes, family history of diabetes, and risk of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:943-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanyal AJ, Banas C, Sargeant C, Luketic VA, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Shiffman ML, Heuman D, Coterrell A, Fisher RA. Similarities and differences in outcomes of cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2006;43:682-689. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Charlton MR, Burns JM, Pedersen RA, Watt KD, Heimbach JK, Dierkhising RA. Frequency and outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1249-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 835] [Cited by in RCA: 855] [Article Influence: 61.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Clark JM, Bass NM, Van Natta ML, Unalp-Arida A, Tonascia J, Zein CO, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, McCullough AJ. Clinical, laboratory and histological associations in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;52:913-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bhala N, Angulo P, van der Poorten D, Lee E, Hui JM, Saracco G, Adams LA, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Topping JH, Bugianesi E. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis: an international collaborative study. Hepatology. 2011;54:1208-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hui JM, Kench JG, Chitturi S, Sud A, Farrell GC, Byth K, Hall P, Khan M, George J. Long-term outcomes of cirrhosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis compared with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:420-427. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Reddy SK, Steel JL, Chen HW, DeMateo DJ, Cardinal J, Behari J, Humar A, Marsh JW, Geller DA, Tsung A. Outcomes of curative treatment for hepatocellular cancer in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:1809-1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sabaté JM, Jouët P, Harnois F, Mechler C, Msika S, Grossin M, Coffin B. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with morbid obesity: a contributor to severe hepatic steatosis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:371-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nazim M, Stamp G, Hodgson HJ. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis associated with small intestinal diverticulosis and bacterial overgrowth. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:349-351. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Fracanzani AL, Valenti L, Russello M, Miele L, Bertelli C, Bellia A, Masetti C, Cefalo C, Grieco A, Marchesini G. Gallstone disease is associated with more severe liver damage in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Loria P, Lonardo A, Lombardini S, Carulli L, Verrone A, Ganazzi D, Rudilosso A, D’Amico R, Bertolotti M, Carulli N. Gallstone disease in non-alcoholic fatty liver: prevalence and associated factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1176-1184. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Overview of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). HCUP Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2012; Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jspAccessed January 8, 2013. |

| 25. | Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2010. HCUP. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2012; Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2010.jspAccessed January 8, 2013. |

| 26. | Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. HCUP Databases. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2012; Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jspAccessed January 9, 2013. |

| 27. | Eckel RH, Alberti KG, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2010;375:181-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 791] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith SC. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8720] [Cited by in RCA: 10567] [Article Influence: 660.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gonnella JS, Louis DZ, Gozum MVE, Callahan CA, Barnes CA. Disease Staging: Clinical Criteria. Thomson Reuters. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/Disease%20Staging%20V5.22%20Clinical%20Criteria.pdfAccessed January 9, 2013. |

| 30. | Averill RF, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, Bonazelli J, McCullough EC, Steinbeck BA. All patient refined diagnosis related groups. 3M. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/ARP-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdfAccessed January 9, 2013. |

| 31. | Ilan Y. Leaky gut and the liver: a role for bacterial translocation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2609-2618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, Fearnside J, Tatoud R, Blanc V, Lindon JC. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12511-12516. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, Montalto M, Cammarota G, Ricci R, Mascianà R, Forgione A, Gabrieli ML, Perotti G. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877-1887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1133] [Cited by in RCA: 1102] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Ramos-De la Medina A, Remes-Troche JM, Roesch-Dietlen FB, Pérez-Morales AG, Martinez S, Cid-Juarez S. Routine liver biopsy to screen for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) during cholecystectomy for gallstone disease: is it justified? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:2097-102; discussion 2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Patel A, Harrison SA. Hepatitis C virus infection and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2012;8:305-312. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Bedossa P, Moucari R, Chelbi E, Asselah T, Paradis V, Vidaud M, Cazals-Hatem D, Boyer N, Valla D, Marcellin P. Evidence for a role of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in hepatitis C: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2007;46:380-387. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Brunt EM, Ramrakhiani S, Cordes BG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Janney CG, Bacon BR, Di Bisceglie AM. Concurrence of histologic features of steatohepatitis with other forms of chronic liver disease. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:49-56. [PubMed] |