INTRODUCTION

Most small cell carcinomas occur in the lung, and extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma comprises only 2.5%-4% of all small cell carcinoma cases[1,2]. These malignancies are now considered to be distinct clinicopathological entities from small cell lung cancer, and there is little consensus regarding the optimal treatment strategy in such cases. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas are rarely found in the trachea, larynx, thymus, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, prostate, gallbladder, skin, breast, and uterine cervix, and they are even rarer in the liver or biliary tract[3]. To the best of our knowledge, only 10 cases of primary small cell carcinomas of the liver have been reported in the English literature[4-10].

Here, we report the case of a patient with small cell carcinoma of the liver and biliary tract initially presenting with atypical chest pain without jaundice.

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with a 7-d history of anorexia and chest pain. On admission, she was afebrile, her blood pressure and pulse rate were normal, and she appeared well nourished despite the recent anorexia. During the work-up for chest pain, an electrocardiogram showed a normal sinus rhythm and an echocardiogram showed no significant functional abnormality. The scleras were not icteric. The abdomen was mildly distended, with tenderness in the right upper quadrant. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4500/mm3 (normal range, 6000-10000/mm3); hemoglobin, 12.1 g/dL (normal range, 12-16 g/dL); platelet count, 199000/mm3 (normal range, 130000-450000/mm3); serum albumin, 3.8 g/dL (normal range, 3.0-5.0 g/dL); aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 101 U/L (normal range, 5-37 U/L); alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 64 U/L (normal range, 5-40 U/L); alkaline phosphatase, 720 U/L (normal range, 39-117 U/L); gamma-guanosine-5’-triphosphate, 215 U/L (normal range, 7-49 U/L); total bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL (normal range, 0.2-1.2 mg/dL); and proBNP, 170.6 pg/mL (normal range, 0-125 pg/mL). Coagulation profiles were within normal limits. After confirming the absence of a significant cardiac problem, we performed esophagogastroscopy and colonoscopy; however, these investigations also yielded no significant findings, except for that of chronic atrophic gastritis. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a lobulated soft tissue mass measuring 10.1 cm and located in the liver, common hepatic duct, common bile duct, gall bladder, and hepatoduodenal ligament. The intrahepatic duct was dilated, and the tumor had invaded both the common hepatic artery and main portal vein (Figure 1); multiple enlarged lymph nodes were present near the celiac and common hepatic arteries and in the left gastric and aortocaval spaces. Additional laboratory studies showed that CA19-9 concentration was 12.57 U/mL (normal range, 0-37 U/mL) and α-fetoprotein (AFP) concentration was 2.19 ng/mL (normal range, 0-10.9 ng/mL). Concentrations of carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) and PIVKAII were not assessed.

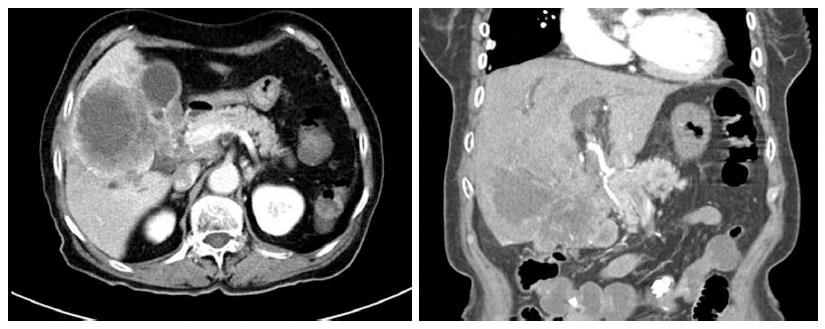

Figure 1 Findings of initial abdominal computed tomography.

Computed tomography showed a large mass located in the liver, common hepatic duct, and common bile duct.

These findings led to clinical suspicion of cholangiocarcinoma, but the patient refused to undergo a biopsy and was discharged. However, four weeks later, the patient visited the hospital with jaundice. At this second visit, laboratory analysis of the patient’s blood provided the following results: AST, 566 U/L; ALT, 261 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 6783 U/L; gamma-GTP, 476 U/L; total bilirubin, 25.8 mg/dL; and direct bilirubin, 19.8 mg/dL. A CT scan of the pancreas and biliary duct revealed a large mass in the right lobe of the liver as well as an obstruction of the hilar duct (Figure 2). An ultrasonography-guided gun biopsy was performed, and pathological analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a tumor consisting of tightly packed nests and diffuse irregularly shaped sheets of cells with areas of necrosis (Figure 3). The tumor cells were of small-to-intermediate size with hyperchromatic, round-to-oval nuclei and scanty, poorly defined cytoplasm. The nuclear chromatin was finely granular, and nucleoli were absent or inconspicuous. Very few cell borders were visible, and there was frequent nuclear molding (Figure 3). The tumor cells were immunoreactive for synaptophysin and CD 56, but negative for hepatocyte-specific antigen (HSA) and thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1. The Ki-67 index was high (more than 80%), and approximately 5 mitotic cells/10 HPF were observed. Taken together, these findings led us to diagnose small cell carcinoma (Figure 4). On the basis of the World Health Organization 2010 classification for neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)/neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), we identified the carcinoma as a grade 3 (G3) NEC (small cell type).

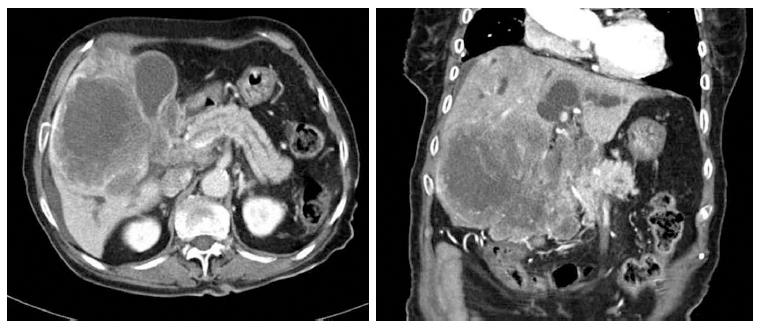

Figure 2 Computed tomography scan obtained before biopsy.

One month after the first visit, a computed tomography scan of the pancreas and biliary duct revealed that the large mass in the right lobe of the liver had grown and that there was an obstruction of the hilar duct.

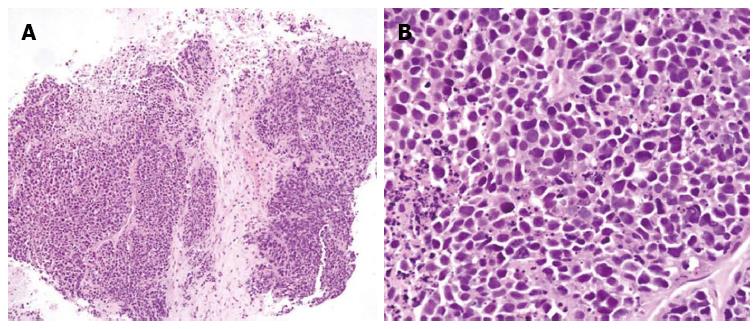

Figure 3 Tumor consisted of tightly packed nests and diffuse, irregularly shaped sheets of cells with necrotic areas.

A: The tumor cells were of small-to-intermediate size with hyperchromatic, round-to-oval nuclei and scanty, poorly defined cytoplasm (HE, × 100); B: The nuclear chromatin was finely granular, and nucleoli were absent or inconspicuous. Cell borders were rarely seen, and nuclear molding was common (HE, × 400).

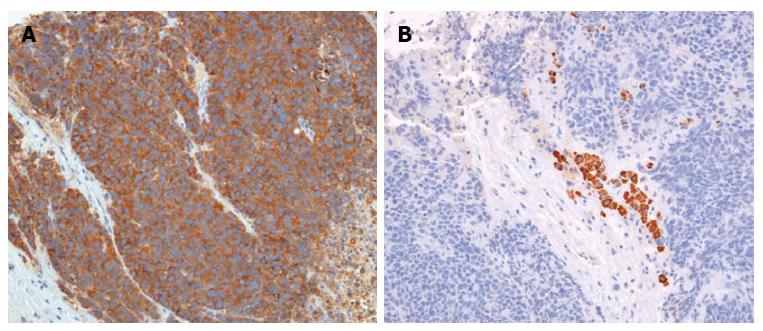

Figure 4 Immunohistochemical findings (× 200).

The tumor cells were immunoreactive for synaptophysin (A) and negative for hepatocyte-specific antigen (B).

The tumor was unresectable; therefore, palliative chemotherapy was considered to be the best treatment option. However, the patient refused chemotherapy because of her advanced age and poor health. Hence, only supportive care, including percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, was provided, and the patient died 8 wk after the diagnosis was confirmed.

DISCUSSION

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas represent only 0.1%-0.4% of all cancer cases[11,12]. Most small cell carcinomas arise in the lung or bronchial trees as small cell lung cancers (SCLCs). However, cases of extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas are gradually becoming more common, and there have been reports of small cell carcinomas in both the gall bladder[13] and pancreas[14]. A few studies have reported small cell NEC of the ampulla of Vater[15,16]. However, reports of small cell carcinoma of the liver or common bile duct, as in the present case, are extremely rare.

Differential diagnosis is important to exclude pulmonary small cell carcinoma. In most cases, a finding of occult extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is subsequently found to be a distant metastasis from an undetected small cell lung cancer. To exclude this possibility, chest radiography and CT, and/or bronchoscopic examination with appropriate biopsies and sputum cytology are required. In addition, growing evidence suggests that positron emission tomography (PET) is also sufficiently sensitive to rule out SCLC[17-19]. In the present case, results of sputum cytology were negative for malignancy, and there was no evidence of lung cancer on chest CT, making bronchoscopy unnecessary.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas shows structural features of both primitive epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation[17]. Neuroendocrine carcinoma arises from embryonic neural crest cells, which migrate to the bronchopulmonary system and gastrointestinal tracts during development. However, these cells do not usually migrate to the liver and bile duct; this may be the reason for the rare occurrence of neuroendocrine tumors of the liver and bile duct[1,20].

Small cell carcinoma can be distinguished from other carcinomas or lymphomas that have cells of a similar size. Under light microscopy, the diameter of small cell carcinoma cells is generally 2 or 3 times greater than that of a small lymphocyte. In addition, small cell carcinoma cells are spindle-like, have a fusiform or polygonal shape, and tend to grow in sheets or ribbon- or rosette-like patterns. Extensive necrosis and high mitotic rates are also typical features that differentiate small cell carcinoma from atypical carcinoid tumors[5].

Furthermore, several distinct immunohistochemical features associated with extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma are potentially important in distinguishing it from hepatic metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma[21-24]; unfortunately, the results of previous studies are somewhat inconsistent in this respect. Ryu et al[4] reported an 8 cm-sized small cell carcinoma of the liver that was positive for CD56/C-kit/synaptophysin and negative for TTF-1. Zanconati et al[7] studied 3 cases and found that all of the tumors were positive for AE1/AE3, CK8, CK18, CK19, and NSE and negative for S-100/CEA, and that 2 of them were AFP positive. Frazier et al[25] reported a case of small cell carcinoma of the liver in which the patient underwent hepatic segmentectomy and adjuvant etoposide/cisplatin therapy. The tumor in this case was positive for CD56/NSE/c-kit/synaptophysin/mixed CK/EMA and negative for CK7, CK8, CK19, CK20, AFP, CEA, vimentin, and desmin/TTF-1/AFP. In the present case, the tumor was positive for both CK and synaptophysin, weakly positive for CD56, and negative for HSA. These tumor cells originate from multipotent stem cells that can differentiate into various cell types; this may explain the frequent coexistence of mixed tumors with various immunohistochemical features.

Small cell carcinoma frequently shows distant metastasis and consequently has a poor prognosis. Correspondingly, patients with small cell lung cancer generally have poor long-term survival. However, some cases of good long-term survival have been reported in patients with extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Little is known about the survival of patients with small cell carcinoma of the liver; generally, the clinical course of this condition is not well described, and reports of patient survival vary. Zanconati et al[7] reported two cases in which the patients died soon after diagnosis, and treatment could not be initiated. In contrast, Sengoz et al[6] reported two cases of extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma of the liver, in which one patient survived for 13 mo after chemotherapy and the other survived 67 mo after receiving right hemihepatectomy. Choi et al[10] reported the case of a patient who survived more than 18 mo after receiving treatment with oral etoposide alone.

It is often not possible to effectively treat small cell carcinoma of the biliary system with surgical resection alone. As an alternative, Hazama et al[26] performed surgical resection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of the common bile duct, and Okamura et al[27] suggested that multimodality treatment including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection, and adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with small cell carcinoma of the biliary system. The generally accepted optimal treatment for extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is appropriate surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. However, Levenson asserted that there is no survival benefit from using surgery to treat either small cell lung cancer or extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. This may be because the most important prognostic factor is the extent of disease at diagnosis, when most patients with extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma already have occult metastasis[1].

In the present case, we could not administer palliative chemotherapy because of the patient’s advanced age and very poor performance status. Although there is no established standard treatment for extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma, chemotherapy should be tried if the patient can tolerate it, because this malignancy is often chemosensitive[28]. The recommended chemotherapy regimen for extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is the same as that for small cell lung cancer[10]. Furthermore, for patients who are able to undergo surgical resection, platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy is also advisable, because it can reduce the chance of systemic recurrence[29-31].

In previous reports of primary small cell carcinoma of the liver or bile duct, patients usually presented with jaundice, a palpable mass, or abdominal discomfort as their first symptom. Despite its rarity, liver and bile duct small cell carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of atypical chest pain as this symptom might indicate the presence of an abdominal malignancy.