Published online Nov 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8047

Revised: August 26, 2013

Accepted: September 3, 2013

Published online: November 28, 2013

Processing time: 291 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate single balloon enteroscopy in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunoanastomosis (HJA).

METHODS: The study took place from January 2009 to December 2011 and we retrospectively assessed 15 patients with Roux-en-Y HJA who had signs of biliary obstruction. In total, 23 ERC procedures were performed in these patients and a single balloon videoenteroscope (Olympus SIF Q 180) was used in all of the cases. A transparent overtube was drawn over the videoenteroscope and it freely moved on the working part of the enteroscope. Its distal end was equipped with a silicone balloon that was inflated by air from an external pump at a pressure of ≤ 5.4 kPa. The technical limitations or rather the parameters of the single balloon enteroscope (working length - 200 cm, diameter of the working channel - 2.8 mm, absence of Albarran bridge) showed the need for special endoscopic instrumentation.

RESULTS: Cannulation success was reached in diagnostic ERC in 12 of 15 patients. ERC findings were normal in 1 of 12 patients. ERC in the remaining 11 patients showed some pathological changes. One of these (cystic bile duct dilation) was subsequently resolved surgically. Endoscopic treatment was initialized in the remaining 10 patients (5 with HJA stenosis, 2 with choledocholithiasis, and 3 with both). This treatment was successful in 9 of 10 patients. The endoscopic therapeutic procedures included: balloon dilatation of HJA stenosis - 11 times (7 patients); choledocholitiasis extraction - five times (5 patients); biliary plastic stent placement - six times (4 patients); and removal of biliary stents placed by us - six times (4 patients). The mean time of performing a single ERC was 72 min. The longest procedure took 110 min and the shortest took 34 min. This shows that it is necessary to allow for more time in individual procedures. Furthermore, these procedures require the presence of an anesthesiologist. We did not observe any complications in these 15 patients.

CONCLUSION: This method is more demanding than standard endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography due to altered postsurgical anatomy. However, it is effective, safe, and widens the possibilities of resolving biliary pathology.

Core tip: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) represents a demanding method even in a normal anatomical situation. When a surgically altered gastrointestinal or pancreatobiliary anatomy is present, ERCP becomes even more demanding. Our retrospective study assessed diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) using a single balloon enteroscope in 15 patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunoanastomosis. A comparatively high success rate was achieved in both diagnostic (80%) and therapeutic (90%) ERC. This method is both time-consuming and technically demanding. However, it is an effective and safe method that widens the possibilities of resolving biliary pathology in these conditions.

- Citation: Kianička B, Lata J, Novotný I, Dítě P, Vaníček J. Single balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunoanastomosis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(44): 8047-8055

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i44/8047.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8047

Hepaticojejunoanastomosis (HJA) construction is a frequent method of surgical bypass for resolution of pathological conditions of the extrahepatic bile ducts, which enables bile drainage into the small intestine. These are the main groups of indications for HJA construction: (1) benign pathological processes in the papilla of Vater (VP) and terminal common bile duct, which cannot be resolved by endoscopy or surgical resection; (2) local inoperable pathological processes in the VP and distal part of the hepatocholedoch that cannot be resolved radically in patients who are able to undergo surgery; (3) stenoses of the distal part of the hepatocholedoch during expansion of the pancreas (both malignant and benign) stenosing the common bile duct; (4) iatrogenic or traumatic damage of the hepatocholedoch (e.g., after laparoscopic cholecystectomy) leading to bile leak or stenosis that cannot be resolved by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), leaving a proximal section of the hepatic duct long enough to enable anastomosis; (5) HJA stenosis; and (6) congenital bile duct anomaly with proximal section of the extrahepatic bile ducts in good condition.

Bile duct injuries during laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy belong to the most serious iatrogenic injuries, with high morbidity and mortality. The increasing number of laparoscopic cholecystectomies has led to an increase in the number of bile duct injuries. Early perioperative detection of these injuries serves as the basis of successful reconstruction of the bile duct where HJA on Roux loop is the gold standard[1]. This procedure is nowadays a standard way of treating injuries of the bile duct and its consequences in the form of stenoses. HJA performed using Roux-en-Y loop (less frequently using omega loop) can be used universally. In general, using this method of bile duct reconstruction for any indication does not lead to mistakes. In contrast to simple end-to-end anastomosis, HJA can be used at any time, in the case of loss-making injury of the bile duct (e.g., excision of its part) or in the case of thin and fine bile duct. HJA can be used in all recent injuries to the bile duct as well as in all adjustments of its stenoses (i.e., in chronic conditions)[2]. It is controversial to perform reoperations for complications of laparoscopic procedures of the bile duct. For reoperations, it is possible to use the da Vinci robotic system, which offers a wide range of visualizing possibilities (fluoroscopy) and movability of instruments (endowrist)[3-5]. The main condition necessary for long-term successful diagnostic results and results of treatment of hepatobiliary diseases is the multidisciplinary approach of surgeons, endoscopists, and interventional radiologists.

One of the serious postoperative complications of HJA is stenosis, with the possible development of cholangitis. Surgery is frequently performed in the unfavorable conditions of inflammatory changes. It is therefore clear that the percentage of restenosis in the area of HJA is comparatively high and reaches about 7% even in the best institutions[6].

The HJA construction (mainly on Roux-en-Y or less frequently on the omega intestinal loop) causes the bile duct orifice into the small intestine to become unreachable by ERCP performed in the standard way (i.e., by lateroscope). That is why biliary drainage used to be provided using the transhepatic approach (i.e., PTC) or surgically.

These patients with Roux-en-Y HJA and with signs of biliary obstruction have therefore in the past been a challenge for endoscopists due to the absence of endoscopic access to enterobiliary anastomosis[7,8].

Single balloon enteroscopy has proved to be effective for deep intubation of the small intestine. The basic technique of performing single balloon enteroscopy has been described extensively in the literature[9,10].

The use of a balloon enteroscope (initially a double balloon and recently also a single balloon) has resulted in achievement of enteroenteroanastomosis, and then bilioenteral anastomosis at the distal end of the afferent intestinal loop[11]. ERC was performed in our group of patients with Roux-en-Y HJA by single balloon enteroscopy. Using standard ERCP, in comparison with a lateroscope, one has to take account of certain technical limitations caused by the current balloon enteroscopes: (1) extreme working length of a single balloon enteroscope - 200 cm; (2) small diameter of the working channel of the single balloon enteroscope - 2.8 mm; and (3) absence of Albarran bridge in a single balloon enteroscope. These technical limitations or parameters show the necessity to use suitable endoscopic instrumentation.

ERCP is considered to be a technically demanding procedure of digestive endoscopy and the presence of surgically altered gastrointestinal or pancreatobiliary anatomy makes it even more difficult[12,13].

The aim of this retrospective study was to analyze and evaluate our experience in using single balloon enteroscopy in diagnostic and therapeutic ERC in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA.

The study took place from January 2009 to December 2011 and we retrospectively assessed 15 patients (7 men, average age: 55 years; 8 women, average age: 53 years) with Roux-en-Y HJA, who had signs of biliary obstruction.

Altogether 23 ERC procedures were performed in these 15 patients with Roux-en-Y HJA using a single balloon videoenteroscope (Olympus SIF Q 180). Its working length was 200 cm, the outer diameter was 9.2 mm, and the diameter of the working channel was 2.8 mm. A transparent overtube was drawn over a single balloon enteroscope and it freely moved on the working part of the enteroscope. The overtube was 13.2 mm in diameter and 140 cm long. The distal end was equipped with a silicon balloon that was filled with air from an external pump up to a maximum pressure of 5.4 kPa. Inflation and deflation of this silicon balloon were performed by means of the external pump control.

The examination was performed after a 12-h fast. This endoscopic procedure was both time consuming and technically demanding and required the presence of an anesthesiologist. The mean time to perform the procedure was 72 min. The longest procedure took 110 min and the shortest took 34 min.

During the procedure, the patient lay on the left side and received intravenous sedation (mainly in various combinations) with: midazolam 1-5 mg, sufentanil 5-10 µg, and propofol 20-40 mg repeatedly, to a maximum dose of 200 mg. Buscopan was used after reaching the blind end of the afferent intestinal loop when looking for the HJA orifice.

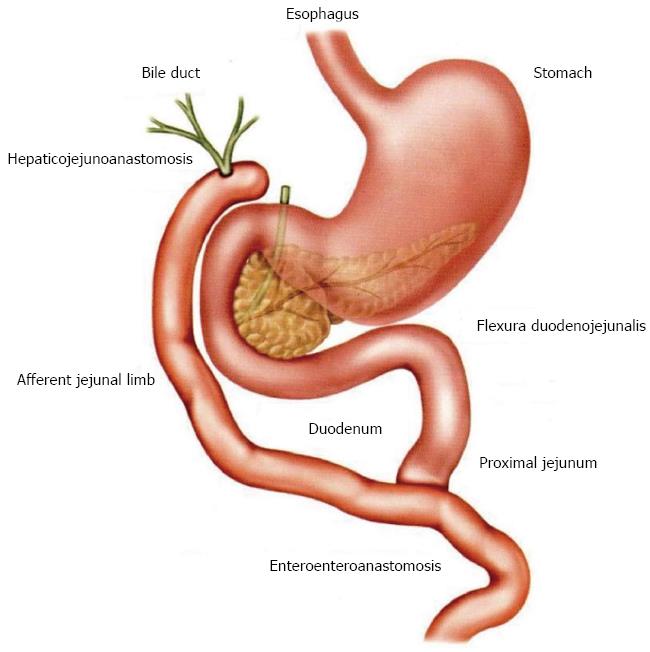

As can be seen in the schematic image with Roux-en-Y HJA (Figure 1), if an endoscopist wishes to reach the target location, that is, the orifice of the HJA, he/she needs to cover a long distance using a single balloon enteroscope - namely the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, duodenojejunal flexure, proximal jejunum, enteroenteroanastomosis, and afferent intestinal loop, where, at its distal end, 5-6 cm before the blind end of the intestinal loop, lies the orifice of the HJA. Non-ionic iodinated contrast medium (Omnipaque 300) was used for X-ray imaging of the biliary system.

As already mentioned above, the technical limitations or parameters of the single balloon enteroscope (working length - 200 cm, diameter of the working channel - 2.8 mm, absence of Albarran bridge) necessitate the use of special endoscopic instrumentation.

First, a cannula (width 6 Fr and length 330 cm, or width 7 Fr and length 312 cm; Cook Co., Bloomington, IN, United States) was used for cannulation of the orifice of the HJA and the adjoining bile ducts. Later, a triple-lumen extraction balloon was used more frequently for cannulation of the orifice of the HJA, which enabled simultaneous application of the contrast medium and insertion of the guidewire, which made cannulation significantly more effective. This triple-lumen extraction balloon is described below, and it is used, in addition to cannulation of the orifice of the HJA, for endoscopic extraction of choledocholithiasis.

An especially long guidewire of 600 cm (width 0.035 inches; Cook) was used specifically for this type of procedure using a single balloon enteroscope. HJA stenosis was endoscopically dilated by a bougie dilator (7 Fr) and by a balloon dilator (Cook Co., dilatation balloon type QBD, diameter 10 mm, balloon length 3 cm, designated for 2.8 mm diameter working channel, total length of instrument 320 cm). This balloon dilator was used for dilation under a pressure of 3 atm for 2 min.

Choledocholithiasis was endoscopically extracted using the above mentioned triple-lumen extraction balloon (Cook, TXR- HE, width 6.6 Fr, length 275 cm). Plastic biliary drains - width 7 Fr (and in 1 patient also 8.5 Fr), length 3-5 cm (Medinet or Cook or MSA) - were inserted endoscopically. Apart from others, Cook pusher, width 7 Fr, length 320 cm, was used. In cases of biliary obstruction, these inserted biliary drains were endoscopically removed using a polypectomy loop (Olympus).

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of St. Anne’s University Hospital Brno. Written informed consent to perform diagnostic and therapeutic ERC using a single balloon enteroscope was obtained from all the patients.

In the majority of patients (12/15), HJA construction was required for iatrogenic lesions of the common bile duct after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In the remaining three patients HJA was required: (1) after resection of the head of the pancreas for chronic pancreatitis; (2) congenital malformation of the common bile duct; and (3) after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) for primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Our patients are described in Table 1 and a detailed description of each patient follows below.

| n | Age/sex | Cause of HJA | Success of diagnostic ERC | Finding on diagnostic ERC | No. of ERC | Characteristics and No. of endoscopic therapeutic procedures |

| 1 | 49/F | ILC after LCE | Yes | HJA stenosis | 3 | BD-3x, EBD-2x |

| 2 | 64/F | Condition after RHP (CHP) | Yes | HJA stenosis | 1 | BD-1x |

| 3 | 26/F | Congenital malformation choledochus (CBD) | Yes | Cystic dilatation choledochus (CBD) | 1 | Surgical solution |

| 4 | 60/M | ILC after LCE | No | HJA found but not probed into | 1 (SBE) | Solved by PTC and PTD |

| 5 | 67/M | ILC after LCE | Yes | CDL | 1 | ECDL-1x |

| 6 | 57/F | ILC after LCE | Yes | HJA stenosis + CDL | 2 | BD-1x, ECDL-1x |

| 7 | 52/M | ILC after LCE | Yes | HJA stenosis + CDL | 2 | BD-1x, ECDL-1x |

| 8 | 29/M | Condition after OLT (PSC) | Yes | HJA stenosis | 3 | BD-2x, EBD-2x |

| 9 | 64/M | ILC after LCE | Yes | Normal ERC results | 1 | Without endoscopic treatment |

| 10 | 48/F | ILC after LCE | Yes | HJA stenosis + CDL | 2 | BD-1x, ECDL-1x, EBD-1x |

| 11 | 56/F | ILC after LCE | Yes | too narrow HJA stenosis | 1 | Therapeut. ERC impossible, condition solved by PTC and PTD |

| 12 | 59/F | ILC after LCE | Yes | CDL | 1 | ECDL-1x |

| 13 | 63/F | ILC after LCE | No | HJA not found at all | 1 (SBE) | Solved by PTC and PTD |

| 14 | 59/M | ILC after LCE | No | HJA found but not probed into | 1 (SBE) | Solved by PTC and PTD |

| 15 | 54/M | ILC after LCE | Yes | HJA stenosis | 2 | BD-2x, EBD-1x |

ERC was performed three times in patient 1 (49-year-old woman). A narrow HJA stenosis was found during the first ERC procedure. Endoscopic balloon dilation of this HJA stenosis was subsequently performed, followed by endoscopic insertion of an 8.5 Fr plastic biliary drain into the bile duct, which completely bridged the HJA stenosis. Another ERC procedure was performed under the same conditions 1 mo later. No complications occurred during this month. Initially, an 8.5 Fr biliary drain was endoscopically extracted. After that, a control ERC was performed, showing that the original HJA stenosis was less prominent. Subsequently, repeat endoscopic balloon dilation of the HJA stenosis was performed. At the end of the second ERC session, an 8.5 Fr plastic biliary drain was repeatedly inserted into the bile duct. A third ERC was performed under the same conditions 1 mo later. An 8.5 Fr biliary drain was endoscopically extracted and a control ERC was performed, which showed a smaller HJA stenosis compared with the previous ERC. Another endoscopic balloon dilation of the small HJA stenosis was performed followed by control ERC. The results were satisfactory, showing almost no HJA stenosis. The procedure was then finished. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC in this patient were therefore successful. The patient had no complications after the first ERC.

ERC was performed once in patient 2 (64-year-old woman) and there was only a slight manifestation of HJA stenosis. Endoscopic balloon dilation of this HJA stenosis was subsequently performed followed by control ERC, with satisfactory results and absence of HJA stenosis. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

Successful diagnostic ERC was performed once in patient 3 (26-year-old woman) and showed cystic dilation of the bile duct. The condition was primarily resolved surgically, that is, without any attempt to perform endoscopic therapy.

The orifice of the HJA was found in patient 4 (60-year-old man). However, the attempt to probe the orifice was not successful, therefore, ERC was not performed. This was a case of cannulation failure, thus, the condition had to be resolved by PTC and percutaneous transhepatic drainage (PTD).

ERC was performed once in patient 5 (67-year-old man) and it showed slight choledocholithiasis. Endoscopic extraction of the choledocholithiasis using a balloon followed. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

ERC was performed twice in patient 6 (57-year-old woman) and slight HJA stenosis and choledocholithiasis were found. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the HJA stenosis was performed during the first ERC, followed by endoscopic balloon extraction of the choledocholithiasis. Control ERC showed satisfactory results for the biliary tree. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

ERC was performed twice in patient 7 (52-year-old man). The first ERC showed slight HJA stenosis and choledocholithiasis. Balloon dilation of the HJA stenosis was performed first, followed by endoscopic extraction of the choledocholithiasis using an extraction balloon. Control ERC showed satisfactory results in the biliary tree. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

Patient 8 (29-year-old man) underwent HJA construction for a condition that developed after OLT for PSC. ERC was performed three times. The first ERC showed a narrow HJA stenosis. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the stenosis was subsequently performed, followed by endoscopic insertion of a 7 Fr plastic biliary drain into the bile duct, which completely bridged the HJA stenosis. The second ERC was performed under the same conditions 1 mo later. No complications occurred during that month. First, a 7 Fr biliary drain was endoscopically extracted. After that, control ERC was performed, showing that the original HJA stenosis was less prominent. Repeated endoscopic balloon dilation of the HJA stenosis was performed. At the end of the second ERC session, a 7 Fr plastic biliary drain was inserted into the bile duct. Third, control ERC was performed under the same conditions 6 wk later. A 7 Fr biliary drain was endoscopically extracted and control ERC was performed, showing significant improvement of the HJA stenosis, which was in fact unnoticeable. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC in this patient were therefore successful.

Successful diagnostic ERC was performed once in patient 9 (64-year-old man) and showed normal findings.

ERC was performed twice in patient 10 (48-year-old woman). The first ERC showed HJA stenosis and slight choledocholithiasis. Balloon dilation of the HJA stenosis was performed first, followed by endoscopic extraction of the choledocholithiasis using an extraction balloon. A 7 Fr plastic biliary drain was subsequently inserted into the bile duct, completely bridging the HJA stenosis. Control ERC in 4 wk (i.e., during the second ERC session) showed satisfactory findings in the bile duct. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

ERC was performed once in patient 11 (56-year-old woman) and prominent HJA stenosis was found. Therapeutic ERC, that is, insertion of a balloon or biliary drain into the HJA stenosis, was not possible because the stenosis was too narrow. This led to PTC and PTD. Successful diagnostic ERC was therefore performed once in this patient.

ERC was performed once in patient 12 (59-year-old woman) and slight choledocholithiasis was found. Endoscopic extraction of the choledocholithiasis using an extraction balloon was subsequently performed. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC were therefore successful.

The area of the distal end of the afferent intestinal loop was reached by single balloon enteroscopy in patient 13 (63-year-old woman), nevertheless the HJA was not found. ERC was therefore not performed. This was a case of cannulation failure, thus, the condition had to be resolved by PTC and PTD.

The orifice of the HJA was found in patient 14 (59-year-old woman), nevertheless, the attempt to probe the orifice was not successful. ERC was therefore not performed. This was a case of cannulation failure, thus, the condition had to be resolved by PTC and PTD.

ERC was performed once in patient 15 (54-year-old man). The first ERC showed HJA stenosis. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the stenosis was performed, followed by endoscopic insertion of a 7 Fr plastic biliary drain into the bile duct, which completely bridged the HJA stenosis. The second ERC was performed under the same conditions 1 mo later. No complications occurred during that month. First, a 7 Fr biliary drain was endoscopically extracted. After that, control ERC was performed, showing marked improvement, with the original HJA stenosis being almost unnoticeable. In spite of that, endoscopic balloon dilation of the area of the HJA stenosis was performed. At the end of the second ERC session, control ERC was performed, showing almost normal findings, which means that the original HJA stenosis was no longer noticeable. Both the diagnostic and therapeutic ERC in this patient were therefore successful.

The results clearly show that cannulation was successful in diagnostic ERC in 12 of 15 patients (80% diagnostic success rate). The diagnostic ERC findings in these patients are shown in Table 2. Normal ERC findings were present in one of the 12 patients. ERC in the remaining 11 patients showed some pathological findings. One of these cases (cystic dilation of the bile duct) was subsequently resolved by surgery.

| Results in ERC | No. of patients |

| Normal results | 1 |

| Cystic dilation of the bile duct | 1 |

| HJA stenosis | 5 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 2 |

| HJA stenosis + choledocholithiasis | 3 |

| Total | 12 |

Endoscopic treatment was started immediately after diagnostic ERC in the remaining 10 patients (5 with HJA stenosis, 2 with choledocholithiasis, and 3 with both conditions). This treatment was successful in nine patients (90% therapeutic success rate). Therapeutic ERC was not successful in the other patient due to an extremely narrow HJA stenosis. This condition was resolved by PTC and PTD.

Endoscopic therapeutic procedures were performed as follows. Balloon dilatation of HJA stenosis was performed a total of 11 times in seven patients; choledocholithiasis extraction was performed a total of five times in five patients; plastic biliary stent insertion was performed a total of six times in four patients; and removal of a biliary stent inserted by our team was performed a total of six times in four patients.

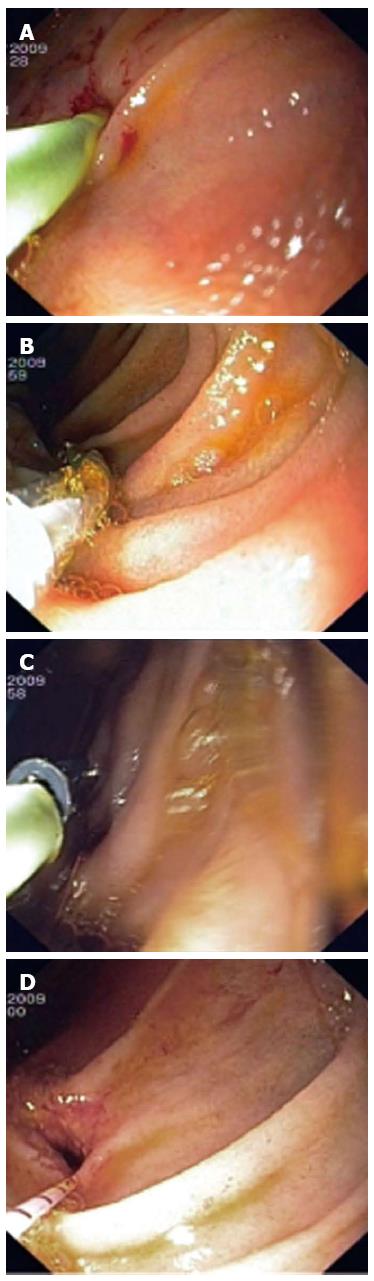

Some of these endoscopic procedures are presented in Figures 2 and 3.

Cannulation failure was recorded in three of 15 patients. Causes of failure were: one patient in whom HJA was not found at all; and two cases in which HJA was found but not probed. All three cases were resolved using PTC and PTD.

There were no complications in our group of 15 patients.

It is also important to draw attention to some of the pitfalls that we encountered and resolved when performing ERC. (1) Fixing an overtube closely in front of the anastomosis in the area of an enteroenteroanastomosis is not recommended because the overtube, in case of the entrance to the afferent intestinal tube being at an acute angle, made insertion of the enteroscope harder; (2) The afferent intestinal loop could be identified by finding its blind end, and bilioenteral anastomosis can be found a few (5-6) centimeters before this blind end; (3) We suggest using endoscopic accessorium of diameter no larger than 7 Fr in the working channel of the single balloon enteroscope (2.8 cm diameter). Based on our personal experience, the use of an 8.5 Fr dilator and biliary drain, or their insertion via the working channel, was difficult. A 7 Fr dilator was much easier to use for dilation and was followed by the use of a dilation balloon. Biliary drainage was, in indicated cases, easier to perform using two 7 Fr drains; and (4) It is advised to straighten the overtube during extraction of the enteroscope from the overtube by manipulation under skiascopic control but, at the same time, it is necessary to prevent the creation of curves that are small in diameter because they tend to break after the removal of the enteroscope, and make repeated insertion complicated.

Single or double balloon enteroscopy enables us to reach even the more distant parts of the small intestine. It is therefore reasonable that this examination method began to be used also for reaching the orifice of the bile duct under conditions of altered anatomy after surgical procedures, when the bile ducts become unreachable by standard lateroscopy (i.e., using conventional ERCP). Previously, pathological conditions (or biliary obstruction) had to be resolved surgically or using PTC[14].

One of these most frequently resolved problems is bile duct pathology in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA (HJA stenosis, choledocholithiasis in the bile duct above the HJA, or both). If we know the type of surgical procedure, ERC using single balloon enteroscopy can be attempted in these cases[14]. Balloon enteroscopy can enable one to reach the afferent intestinal loop, identify the orifice of the HJA[15-17], perform diagnostic ERC, and if indicated, also perform therapeutic ERC. Originally, the procedure was carried out with double balloon enteroscopy[7,18] and later also with single balloon enteroscopy[13,19-21]. There was a wide range of endoscopic therapeutic procedures performed. These procedures are also being performed in standard ERCP[11]. We used single balloon enteroscopy for diagnostic and therapeutic ERC in our group of 15 patients with Roux-en-Y HJA.

The results of diagnostic and therapeutic ERC using single balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA in other endoscopic centers show that Dellon et al[20] were successful when performing ERC in three of four patients. Neumann et al[21] worked with 13 patients in whom the diagnostic success rate was 62% and the therapeutic success rate 54%. The largest study to date was by Saleem et al[12] who achieved a success rate of 78% (32 of 41 patients) in diagnostic ERC. Wang et al[13] have recently described a group of 13 patients (16 procedures in total). Cannulation success rate was 81% (13 of 16 cases) for diagnostic ERC. Therapeutic ERC was necessary in 10 of these 13 patients and was successful in nine patients (90% therapeutic ERC success rate).

The diagnostic and therapeutic ERC success rates in our study were comparatively high and, at the same time, there were no procedure-related complications. Cannulation success was achieved in 12 of 15 patients (80% diagnostic ERC success rate). Endoscopic treatment was successful in nine of 10 patients (90% therapeutic ERC success rate). Our results in diagnostic and therapeutic ERC are comparable to those of other endoscopic centers dealing with this issue[12,13,20].

As mentioned above, we encountered some pitfalls when performing ERC, which are not addressed in detail by other authors[7,12,19,20]. Nevertheless, they do consider the following: (1) avoidance of fixing an overtube closely in front of an enteroenteroanastomosis at the entrance of the enteroscope into the afferent loop; (2) identification of the afferent loop and the bilioenteral anastomosis; (3) using an endoscopic accessorium of diameter no larger than 7 Fr in the working channel of the single balloon enteroscope (diameter 2.8 cm) - a suggestion based on our own experience; and (4) straightening the overtube during extraction of the enteroscope from the overtube, by manipulation under skiascopic control, and at the same time, preventing creation of curves that are small in diameter, because they tend to break after removal of the enteroscope and make repeated insertion complicated.

No complications, not even acute pancreatitis, appeared in our group of 15 patients. It might be that the altered anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract decreases the risk of complications associated with balloon enteroscopy[7].

In conclusion, it can be stated that ERC using single balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA is more difficult than standard ERCP, due to altered postoperative anatomy, and considerable endoscopic skill and experience is needed in order to perform ERC successfully. CRE requires a lot of time for individual procedures and the presence of an anesthesiologist is essential. The cannulation success rate reached in our group of patients was 80% (12 of 15 patients). Endoscopic treatment was successful in 90% (9 of 10 patients). Most ERC procedures in our group of patients were therapeutic (10 of 12 patients - i.e., 83%). There were no complications in our patients. This method is highly demanding but, at the same time, effective and safe, significantly widening the possibilities of resolving biliary tract diseases.

Single balloon enteroscopy (SBE) was originally and still is used for endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of diseases of the small intestine. It was also introduced in endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunoanastomosis (HJA), especially in cases in which standard ERC (by lateroscopy) was unsuccessful, because it was impossible to reach the area of the HJA.

The need to continue developing and possibly improving equipment (both endoscopes and endoscopic accessories) is still present. They should be better adjusted to the needs of the ERC procedures in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA (enteroscopes with sideways or oblique optics with an elevator, shorter enteroscopes with wider channels specially designed for these procedures, and development of endoscopic accessories of greater length).

When surgically altered gastrointestinal or pancreatobiliary anatomy is present, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography becomes even more demanding than in a normal anatomical situation. In spite of that, we managed to achieve a comparatively high success in diagnostic (80%) and therapeutic (90%) ERC using single balloon enteroscopy in our cohort of 15 patients with Roux-en-Y HJA, and there were no complications after ERC.

ERC using single balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA is time consuming and technically demanding. Nevertheless, it is also an effective and safe method that widens the possibilities of resolving biliary tract diseases. Previously, the only possibility of resolution was using percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography or a surgical approach.

The study reported high-quality results of diagnostic and therapeutic ERC using single balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y HJA. The study retrospectively evaluated 15 patients with Roux-en-Y HJA with signs of biliary obstruction. Altogether, 23 ERC procedures were performed without any complications.

P- Reviewer: Domagk D S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Treska V, Skalický T, Safránek J, Kreuzberg B. [Injuries to the biliary tract during cholecystectomy]. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84:13-18. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Král V, Havlík R, Neoral Č. Hepaticojejunoanastomosis: "golden standard" in the reconstruction of the injured biled duct. Bulletin HPB. 2003;11:66-68. |

| 3. | Vlček P, Korbička J, Jedlička V, Čapov I, Chalupnik S, Dolezel J, Veverkova L, Vlckova P, Dolina J, Bartusek D. Robot-assisted colorectal surgery. Br J Sur. 2009;96:48. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vlček P, Čapov I, Korbička J. Comparison of laparoscopy and robotic assisted procedures on the colorectum. Endoskopie. 2011;20:21. |

| 5. | Vlcek P, Capov I, Jedlicka V, Chalupník S, Korbicka J, Veverková L, Dolezel J, Jerábek J, Wechsler J. [Robotic procedures in the colorectal surgery]. Rozhl Chir. 2008;87:135-137. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ehrmann J, Hůlek P. Hepatologie. 1st ed. Praha: Grada 2010; . |

| 7. | Aabakken L, Bretthauer M, Line PD. Double-balloon enteroscopy for endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with a Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2007;39:1068-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP with the double balloon enteroscope in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1961-1967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tsujikawa T, Saitoh Y, Andoh A, Imaeda H, Hata K, Minematsu H, Senoh K, Hayafuji K, Ogawa A, Nakahara T. Novel single-balloon enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of the small intestine: preliminary experiences. Endoscopy. 2008;40:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Machková N, Bortlík M, Bouzková E, Ďuričová D, Hrdlička L, Lukáš M. Single-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Crohn’s disease – experience of a centre. Gastroent Hepatol. 2011;65:215-219. |

| 11. | Koornstra JJ, Fry L, Mönkemüller K. ERCP with the balloon-assisted enteroscopy technique: a systematic review. Dig Dis. 2008;26:324-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Saleem A, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Petersen BT, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using a single-balloon enteroscope in patients with altered Roux-en-Y anatomy. Endoscopy. 2010;42:656-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang AY, Sauer BG, Behm BW, Ramanath M, Cox DG, Ellen KL, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Single-balloon enteroscopy effectively enables diagnostic and therapeutic retrograde cholangiography in patients with surgically altered anatomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:641-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Haber GB. Double balloon endoscopy for pancreatic and biliary access in altered anatomy (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:S47-S50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mönkemüller K, Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P. ERCP using single-balloon instead of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Endoscopy. 2008;40 Suppl 2:E19-E20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kuga R, Furuya CK, Hondo FY, Ide E, Ishioka S, Sakai P. ERCP using double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Dig Dis. 2008;26:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parlak E, Ciçek B, Dişibeyaz S, Cengiz C, Yurdakul M, Akdoğan M, Kiliç MZ, Saşmaz N, Cumhur T, Sahin B. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography by double balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:466-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mönkemüller K, Weigt J, Treiber G, Kolfenbach S, Kahl S, Röcken C, Ebert M, Fry LC, Malfertheiner P. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Tsuchiya T, Kurihara T, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Umeda J, Moriyasu F. Single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y anastomosis (with video). Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:93-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dellon ES, Kohn GP, Morgan DR, Grimm IS. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with single-balloon enteroscopy is feasible in patients with a prior Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1798-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Neumann H, Fry LC, Meyer F, Malfertheiner P, Monkemuller K. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography using the single balloon enteroscope technique in patients with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Digestion. 2009;80:52-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |