Published online Nov 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7455

Revised: September 26, 2013

Accepted: September 29, 2013

Published online: November 14, 2013

Processing time: 118 Days and 12.2 Hours

AIM: To compare the efficacy and side effects of low-dose amitriptyline (AMT) with proton pump inhibitor treatment in patients with globus pharyngeus.

METHODS: Thirty-four patients who fulfilled the Rome III criteria for functional esophageal disorders were included in this study. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either 25 mg AMT before bedtime (AMT group) or 40 mg Pantoprazole once daily for 4 wk (conventional group). The main efficacy endpoint was assessed using the Glasgow Edinburgh Throat Scale (GETS). The secondary efficacy endpoints included the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short form health survey [social functioning (SF)-36] and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Treatment response was defined as a > 50% reduction in GETS scores. All patients entering this study recorded side effects at days 1, 8, 15, 22 and 29 using a visual analogue scale.

RESULTS: Thirty patients completed the study. After 4 wk of treatment, the AMT group had a greater response than the conventional group (75% vs 35.7%, P = 0.004). At day 3, the AMT group showed significantly more improvement than the Conventional group in GETS score (3.69 ± 1.14 vs 5.64 ± 1.28, P = 0.000). After 4 wk of treatment, the AMT group showed significantly greater improvement in GETS score and sleep quality than the Conventional group (1.25 ± 1.84 vs 3.79 ± 2.33, 4.19 ± 2.07 vs 8.5 ± 4.97; P < 0.01 for both). Additionally, the AMT group was more likely than the Conventional group to experience improvement in the SF-36, including general health, vitality, social functioning and mental health (P = 0.044, 0.024, 0.049 and 0.005). Dry mouth, sleepiness, dizziness and constipation were the most common side effects.

CONCLUSION: Low-dose AMT is well tolerated and can significantly improve patient symptoms, sleep and quality of life. Thus, low-dose AMT may be an effective treatment for globus pharyngeus.

Core tip: A literature review reveals that there is no single effective treatment for patients with globus pharyngeus. Low-dose amitriptyline (AMT) is extensively used to treat functional gastrointestinal disorders, especially in cases with prolonged severe symptoms and disorders that affect daily function. However, no data regarding the possible effects of AMT in patients with globus pharyngeus are available. In this study, we conclude that low-dose AMT is well tolerated and can significantly improve patient symptoms. Thus, we recommend the use of low-dose AMT for globus pharyngeus.

- Citation: You LQ, Liu J, Jia L, Jiang SM, Wang GQ. Effect of low-dose amitriptyline on globus pharyngeus and its side effects. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(42): 7455-7460

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i42/7455.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7455

Globus pharyngeus is a condition characterized by a nonpainful sensation of a lump in the throat in the absence of true dysphagia or odynophagia; the sensation frequently improves with eating[1]. It is a common condition that accounts for approximately 4% of otolaryngological referrals[2], and it is usually long-lasting, difficult to treat, recurrent and associated with a significant impairment in quality of life. Furthermore, due to the uncertain etiology of globus, it remains difficult to establish standard investigation and treatment strategies for affected patients.

Amitriptyline (AMT) is a tricyclic antidepressant with limited application due to the side effects caused by high doses (100 mg/d). In recent years, low-dose AMT has been shown to be well tolerated and significantly effective in improving the functional gastrointestinal disorders[3-5]. In 1994, Deary et al[6] were the first to attempt a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of AMT in patients with globus pharyngeus. Most patients could not tolerate the side effects of AMT at doses of 50 mg/d to 150 mg/d, resulting in treatment failure. To the best of our knowledge, evidence supporting the possible effects of low-dose AMT in patients with globus pharyngeus has not been reported.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the response rate, onset time, side effects and clinical predictors of symptom response to low-dose AMT treatment in patients with globus pharyngeus.

In this prospective study, we enrolled 34 patients who complained of globus symptoms between September 2011 and January 2013. All patients were between 12 and 65 years of age and were newly diagnosed as having functional esophageal disorders based on the following Rome III criteria[7]: (1) persistent or intermittent, nonpainful sensation of a lump or foreign body in the throat; (2) occurrence of the sensation between meals; (3) absence of dysphagia or odynophagia; (4) absence of evidence that gastroesophageal reflux is the cause of the symptom; and (5) absence of histopathology-based diagnosis of esophageal motility disorders. All included patients fulfilled the criteria for the last 3 mo, with symptom onset at least 6 mo before diagnosis. All patients underwent otolaryngological assessment with neck/thyroid palpation and gastroscopy or laryngoscopy, and none had any organic abnormality on assessment. The following exclusion criteria were adopted: hepatic or renal disease; prostatic disease; pregnancy or breast feeding; known glaucoma; history of seizures; history of thyroid or liver dysfunction; recent use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors; use of any proton pump inhibitor (PPI) or histamine type 2 receptor antagonist during the last 2 mo; use of tranquilizers or antidepressants that may affect esophageal motor function; and moderate to severe anxiety or depression (14-item Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale assessed from 0 to 13 points and 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale assessed from 0 to 17 points).

This study was a prospective, randomized controlled trial in globus pharyngeus patients and was approved by the hospital ethics committee (Clinical trial registration number: ChiCTR-TRC-12001968). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Thirty-four eligible patients were randomized to receive either 25 mg AMT once daily before bedtime or 40 mg Pantoprazole once daily for 4 wk. Treatment was allocated by a simple randomization method using a computer-generated randomization schedule. Ultimately, 17 patients received AMT, and 17 patients received Pantoprazole. The primary endpoint was assessed using the Glasgow Edinburgh Throat Scale (GETS) questionnaire[8]. We observed the onset time and the treatment efficiency on days 3 and 10 and week 4, and evaluated the social functioning (SF)-36 and Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) scores at baseline and at week 4 as secondary endpoints[9,10].

All patients entering this study recorded side effects. The severity of side effects was evaluated using a visual analogue scale (VAS) administered on days 1, 8, 15, 22 and 29 after medication.

The GETS questionnaire provided both the primary and secondary outcomes. It is a validated questionnaire used to rate globus pharyngeus symptoms. The globus symptom score component is based on 10 questions assessing various throat symptoms. Patients subjectively grade their symptoms for each question on a 7-point Likert scale, with 0 being “none” and 7 being “unbearable”. These compiled questions yield a score that represents the severity of the patient’s globus symptoms, with a maximum possible score of 70. The secondary outcome is the somatic distress score, which represents the psychological impact of the patient’s symptoms. This component of the questionnaire is also graded on a 7-point Likert scale, with 0 being ‘‘never’’ and 7 being ‘‘all of the time’’. This yields a maximum total score of 14. Both the overall symptom score and the somatic distress score can be used over time to assess the severity of the disease.

The SF-36 is the most commonly used scale for assessing patient quality of life, and it includes eight dimensions: physical functioning, role-physical (RP), bodily pain, general health (GH), vitality (VT), SF, role-emotional (RE), and mental health (MH). A higher score indicates a better quality of life.

Prepared by psychiatrist Buysse et al[9], the PSQI assesses seven areas, including sleep quality, the time to fall asleep, sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication and daytime dysfunction. In total, 18 items were used for the calculation of the PSQI score. Higher scores represent worse sleep quality, and a score > 7 points indicates the presence of a sleep disorder.

Treatment response was defined as a > 50% reduction in the GETS score. The response was calculated as: [(score at treatment - score at baseline)/score at baseline] × 100. The treatment responses of the two groups were calculated separately.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, United States), and the measurement data are reported as the mean ± SD; baseline parameters and differences between the two treatments were compared using Student’s t test. The scores at baseline and after AMT or Pantoprazole treatment were compared by paired t test. The VAS scores of side effects were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

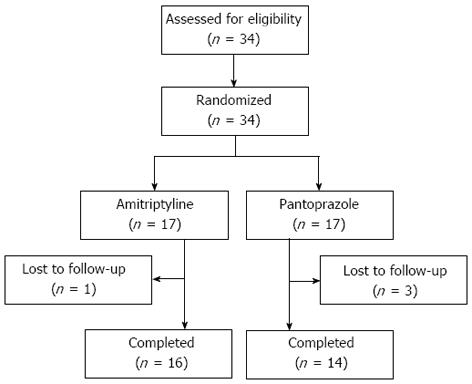

A total of 34 patients with globus symptom were enrolled in the study. All patients were randomized to receive either AMT or Pantoprazole. Of these patients, four were lost to follow-up. A total of 30 patients (AMT 16, Pantoprazole 14) completed the study (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. No differences were observed between the two groups in age, gender, body mass index, smoking habit, alcohol consumption, symptom duration, GETS score or PSQI score.

| Variable | AMT group | Conventional group | P value |

| n = 16 | n = 14 | ||

| Age (yr) | 43.19 ± 10.96 | 42.93 ± 13.1 | 0.953 |

| Gender (male/female) | 6/10 | 5/9 | 1.000 |

| BMI | 21.54 ± 2.09 | 23.01 ± 3.49 | 0.166 |

| Smoking habit | 4 (18.75%) | 3 (21.42%) | 1.000 |

| Alcohol consumption | 6 (37.5%) | 5 (35.71%) | 1.000 |

| Symptom duration (yr) | 1.44 ± 0.66 | 1.54 ± 0.89 | 0.731 |

| GETS | 5.44 ± 1.63 | 5.71 ± 1.38 | 0.623 |

| PSQI | 8.75 ± 4.68 | 8.71 ± 5.27 | 0.984 |

The rate of effectiveness was calculated in the two groups after 4 wk of treatment, the response rate of the AMT group was significantly higher than that of the Conventional group (75% vs 35.7%, P = 0.004, Table 2). Compared with the Conventional group, the GETS scores of the AMT group were significantly improved at days 3 and 10, and week 4 (all P < 0.01, Table 2). Compared with baseline, the GETS scores of the AMT group were significantly reduced at days 3 and 10 and week 4 (all P < 0.05). However, the GETS scores of the Conventional group were significantly reduced only after 4 wk of treatment. The onset time in the AMT group was significantly earlier than that in the Conventional group.

| Variable | AMT group | Conventional group | P value |

| n = 16 | n = 14 | ||

| GETS score | |||

| Baseline | 5.44 ± 1.63 | 5.71 ± 1.38 | 0.623 |

| 3 d | 3.69 ± 1.141 | 5.64 ± 1.28 | 0.000 |

| 10 d | 2 ± 1.711 | 5.36 ± 1.22 | 0.000 |

| 4 wk | 1.25 ± 1.841 | 3.79 ± 2.331 | 0.002 |

| Treatment response | 12 (75) | 5 (35.71) | 0.004 |

| PSQI | 4.19 ± 2.07 | 8.5 ± 4.97 | 0.008 |

| Adverse effect | |||

| Dry mouth | 12 (75) | 4 (28.5) | 0.026 |

| Sleepiness | 11 (68.8) | 2 (14.3) | 0.004 |

| Dizziness | 4 (25) | 1 (7.1) | 0.336 |

| Constipation | 3 (18.8) | 1 (7.1) | 0.602 |

| Palpitations | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Malaise | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

Compared with the Conventional group, the AMT group exhibited significant improvements in the GH, VT, SF, MH scales of the SF-36 (all P < 0.05, Table 3). Compared with baseline, the AMT group exhibited significant improvements in RP, GH, VT, SF, RE and MH (all P < 0.05). The Conventional group experienced significant improvements in only RP, GH and SF (all P < 0.05, Table 3).

| Variable | Baseline | Week 4 | P value | |

| PF | AMT | 95 ± 11.4 | 95.94 ± 11.14 | 0.945 |

| Conventional | 93.93 ± 7.12 | 95.71 ± 4.75 | ||

| RP | AMT | 64.06 ± 37.6 | 81.25 ± 26.611 | 0.929 |

| Conventional | 66.07 ± 37.48 | 80.36 ± 28.041 | ||

| BP | AMT | 89.38 ± 16.52 | 90.63 ± 14.55 | 0.498 |

| Conventional | 85.57 ± 20.68 | 86.29 ± 19.96 | ||

| GH | AMT | 56.75 ± 20.92 | 73 ± 17.571 | 0.044 |

| Conventional | 49.86 ± 22.49 | 58.71 ± 19.571 | ||

| VT | AMT | 70.63 ± 18.15 | 88.44 ± 7.011 | 0.024 |

| Conventional | 71.79 ± 24.7 | 73.21 ± 24.39 | ||

| SF | AMT | 75 ± 18.25 | 92.97 ± 13.671 | 0.049 |

| Conventional | 77.68 ± 18.46 | 81.25 ± 17.511 | ||

| RE | AMT | 68.76 ± 35.42 | 79.18 ± 23.961 | 0.384 |

| Conventional | 61.91 ± 41.05 | 69.05 ± 38.04 | ||

| MH | AMT | 68.75 ± 15.68 | 83.5 ± 101 | 0.005 |

| Conventional | 65.43 ± 19.32 | 69.14 ± 15.72 |

The AMT group also showed a significant improvement in PSQI compared with the Conventional group (4.19 ± 2.07 vs 8.5 ± 4.97, P = 0.008, Table 2). Compared with baseline, the AMT group exhibited significant improvement. However, there were no significant differences in PSQI at baseline and after pantoprazole treatment (P > 0.05).

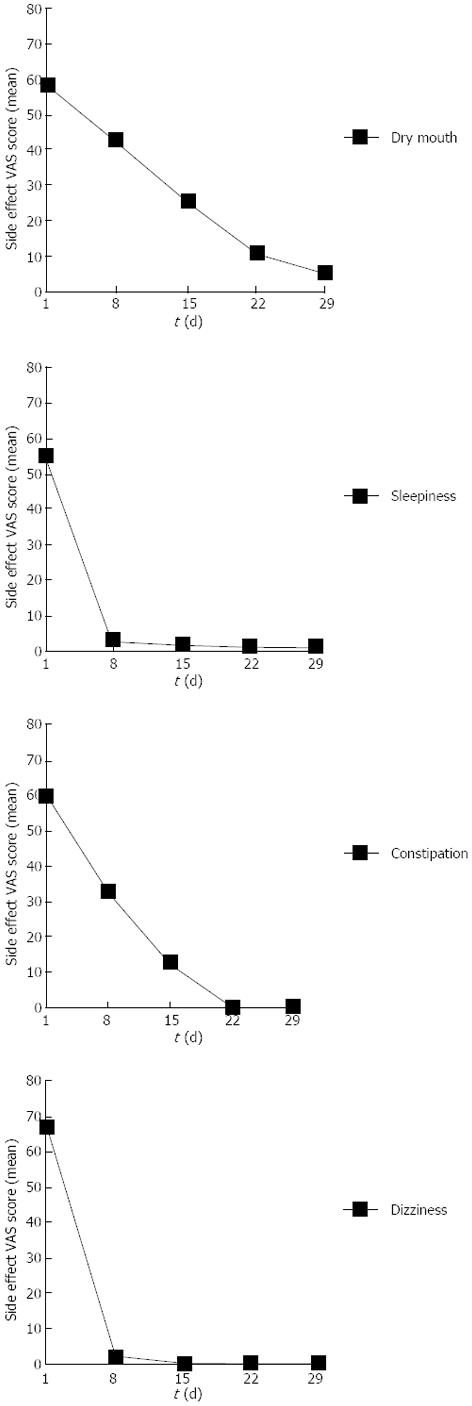

The various adverse events reported in the two treatment groups are shown in Table 2. The incidence rates of dry mouth and sleepiness in the AMT group were significantly higher than in the Conventional group (P = 0.026, P = 0.004, Table 2). The incidence rates of dizziness and constipation were also somewhat higher in the AMT group than in the Conventional group, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.336, P = 0.602, Table 2).

As shown in Figure 2, sleepiness and dizziness almost disappeared within 1 wk. Patients who had dry mouth and constipation symptoms experienced significant relief after receiving AMT for 2 wk. No serious adverse events occurred in either group.

There is no consistent evidence attributing globus to any specific anatomic abnormality, including the cricopharyngeal bar. Although it has been long since it was first described, the etiology of globus pharyngeus is poorly understood. Abnormal upper esophageal sphincter function, esophageal motility disorders, psychological factors, stress, and Helicobacter pylori infection of the cervical heterotopic gastric mucosa have all been suggested as potential causes of globus[11-15]. There is much controversy about the true etiology of globus pharyngeus, and it has been difficult to establish a causal relationship between globus and these other disorders[16]. In addition, esophageal balloon distention can simulate the sensation of globus at low distending thresholds, suggesting some degree of esophageal hypersensitivity[1]. Because there are few controlled studies on the treatment of globus, evidence-based treatment for this disorder is currently not available. Some studies have suggested that gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a major cause of globus[16,17-19]. Therefore, it seems practical to use anti-reflux methods as the first-line treatment for managing patients with globus[11], although this protocol remains under considerable debate. Other established treatment options include speech and language therapy, anti-depressants, and cognitive-behavioral therapy[11,20-22].

Low-dose AMT has been used widely in gastroenterologic practice. Morgan et al[23] demonstrated that the doses for the analgesic and neuromodulatory effects of AMT were below the effective doses of the antidepressant. Huang et al[24] observed that low-dose AMT could reduce visceral sensitivity using the noninvasive drinking-ultrasonography test in healthy volunteers. However, our understanding of the mechanism of action of this agent is limited. A commonly held hypothesis is that AMT, which indirectly stimulates norepinephrine and serotonin receptors by blocking the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, works as a neuromodulator, affecting the brain-gut axis by altering neurotransmitter systems within the limbic system and other pain centers of the brain[25]. In addition, one study showed that AMT can alter sleep patterns[25]. Our study also confirmed that the AMT group showed significantly greater improvement in sleep than the Conventional group. We hypothesize that the overall effects of amitriptyline in patients with globus arise from its central nervous system activity, as altering sleep patterns modulates the regulation of the noradrenergic system of the locus coeruleus (a brain center inhibited during sleep), which alters nociception.

In our study, 5 of 14 (35.7%) patients with globus pharyngeus receiving PPI treatment as a conventional therapy were classified as responders. Dumper et al[26] demonstrated that there was no clinically or statistically significant difference between lansoprazole and placebo at any time point during a 3-mo treatment period. Therefore, it is important to note that although GERD is a condition that is sometimes associated with globus, this does not mean that all globus is GERD-related or that all GERD patients have globus. Thus, PPI treatment in patients with globus may not achieve satisfactory results.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective, randomized controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of a therapeutic low dose of AMT in globus patients. The treatment efficiency of the AMT group was 75%, significantly greater than that of the Conventional group (35.7%). After 3 d of treatment, the symptoms, sleep, and quality of life of the AMT group improved more than those of the Conventional group. During treatment, average cost in the AMT group was also significantly lower than that in the Conventional group.

There are several limitations of this study. First, although many patients with globus symptoms and normal examinations were seen in our clinic, this study included only a small sample of patients with globus. A number of patients had recently started on PPI or were diagnosed with moderate to severe anxiety or depression, and excluding these patients resulted in a decreased number of cases in this study. Second, it is possible that the course of medication in our study was too short; the standard duration of AMT administration in the clinic is 4-12 wk[27]. We also evaluated only the response to short-term PPI treatment and did not investigate the response to long-term PPI treatment (3 or more months).

In conclusion, low-dose AMT is well tolerated and may be effective in reducing the symptoms of patients with globus pharyngeus while also significantly improving sleep and quality of life. However, further studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to verify our results.

We would like to thank Ming-Zhi Xu, Professor of the Guangdong Mental Disorder Research Institute, for his guidance in the use of SF-36 and the anxiety and depression scale. We also express our appreciation to Dr. Su of ENT for his assistance in diagnosing globus pharyngeus.

Low-dose amitriptyline (AMT) is extensively used for treating functional gastrointestinal disorders, although its precise mechanism of action is still not fully understood. In 1994, Deary et al performed the first study investigating the effectiveness of high-dose AMT (50-150 mg/d) in patients with globus pharyngeus. However, most patients could not tolerate the side effects of high doses of AMT, resulting in treatment failure. The effect of low-dose AMT in patients with globus pharyngeus has not been reported.

There is currently a lack of highly effective pharmacotherapy for globus pharyngeus. Low-dose AMT may be a good choice of treatment for patients with globus pharyngeus.

This is the first prospective, randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of a therapeutic low dose of AMT in globus patients. The results revealed that low-dose AMT is well tolerated and can significantly improve patient symptoms, sleep and quality of life.

Low-dose AMT can be significantly effective in improving the symptoms and quality of life of the patients, thereby supporting its clinical applicability for gastrointestinal disorders.

Globus pharyngeus is a physical sensation of a lump in the throat that causes difficulty or discomfort in swallowing. The sensation may also be choking or feeling as though there is a mass lodged in the esophagus. AMT is a tricyclic antidepressant that is extensively used to treat functional gastrointestinal diseases, especially in cases with prolonged severe symptoms and daily functional disorders.

This is an interesting paper evaluating the effect of low-dose AMT on globus pharyngeus. The study is reasonably well done, and the design and outcome assessment are standardized.

P- Reviewers: Sharara AI, Weijenborg PW S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: Ma JY E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Galmiche JP, Clouse RE, Bálint A, Cook IJ, Kahrilas PJ, Paterson WG, Smout AJ. Functional esophageal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1459-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moloy PJ, Charter R. The globus symptom. Incidence, therapeutic response, and age and sex relationships. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108:740-744. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1548-1553. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Teitelbaum JE, Arora R. Long-term efficacy of low-dose tricyclic antidepressants for children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:260-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thoua NM, Murray CD, Winchester WJ, Roy AJ, Pitcher MC, Kamm MA, Emmanuel AV. Amitriptyline modifies the visceral hypersensitivity response to acute stress in the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:552-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Deary IJ, Wilson JA. Problems in treating globus pharyngis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19:55-60. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377-1390. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Harris MB, MacDougall G. Globus pharyngis: development of a symptom assessment scale. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:203-213. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193-213. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lee BE, Kim GH. Globus pharyngeus: a review of its etiology, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2462-2471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Kwiatek MA, Mirza F, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Hyperdynamic upper esophageal sphincter pressure: a manometric observation in patients reporting globus sensation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:289-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Färkkilä MA, Ertama L, Katila H, Kuusi K, Paavolainen M, Varis K. Globus pharyngis, commonly associated with esophageal motility disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:503-508. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Harris MB, Deary IJ, Wilson JA. Life events and difficulties in relation to the onset of globus pharyngis. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:603-615. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Alagozlu H, Simsek Z, Unal S, Cindoruk M, Dumlu S, Dursun A. Is there an association between Helicobacter pylori in the inlet patch and globus sensation? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:42-47. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tsutsui H, Manabe N, Uno M, Imamura H, Kamada T, Kusunoki H, Shiotani A, Hata J, Harada T, Haruma K. Esophageal motor dysfunction plays a key role in GERD with globus sensation--analysis of factors promoting resistance to PPI therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tokashiki R, Yamaguchi H, Nakamura K, Suzuki M. Globus sensation caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002;29:347-351. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Chevalier JM, Brossard E, Monnier P. Globus sensation and gastroesophageal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:273-276. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tokashiki R, Funato N, Suzuki M. Globus sensation and increased upper esophageal sphincter pressure with distal esophageal acid perfusion. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:737-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Khalil HS, Bridger MW, Hilton-Pierce M, Vincent J. The use of speech therapy in the treatment of globus pharyngeus patients. A randomised controlled trial. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2003;124:187-190. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Cybulska EM. Globus hystericus--a somatic symptom of depression? The role of electroconvulsive therapy and antidepressants. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:67-69. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Burns P, O’Neill JP. The diagnosis and management of globus: a perspective from Ireland. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:503-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Morgan V, Pickens D, Gautam S, Kessler R, Mertz H. Amitriptyline reduces rectal pain related activation of the anterior cingulate cortex in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:601-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang W, Jiang SM, Jia L, You LQ, Huang YX, Gong YM, Wang GQ. Effect of amitriptyline on gastrointestinal function and brain-gut peptides: a double-blind trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4214-4220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mertz H, Fass R, Kodner A, Yan-Go F, Fullerton S, Mayer EA. Effect of amitriptyline on symptoms, sleep, and visceral perception in patients with functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:160-165. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Dumper J, Mechor B, Chau J, Allegretto M. Lansoprazole in globus pharyngeus: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;37:657-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rajagopalan M, Kurian G, John J. Symptom relief with amitriptyline in the irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:738-741. [PubMed] |