Published online Nov 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7447

Revised: August 1, 2013

Accepted: August 28, 2013

Published online: November 14, 2013

Processing time: 164 Days and 23.9 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the outcome of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma and to determine the predictors for survival.

METHODS: Between July 2002 and June 2010, we retrospectively enrolled all consecutive patients admitted to our department with a diagnosis of portal cavernoma without abdominal malignancy or liver cirrhosis. The primary endpoint of this observational study was death and cause of death. Independent predictors of survival were identified using the Cox regression model.

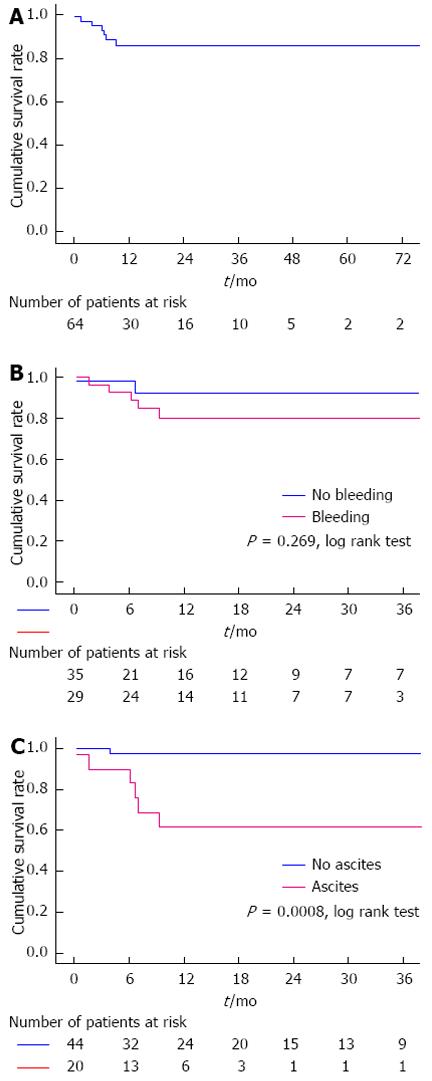

RESULTS: A total of 64 patients were enrolled in the study. During a mean follow-up period of 18 ± 2.41 mo, 7 patients died. Causes of death were pulmonary embolism (n = 1), acute leukemia (n = 1), massive esophageal variceal hemorrhage (n = 1), progressive liver failure (n = 2), severe systemic infection secondary to multiple liver abscesses (n = 1) and accident (n = 1). The cumulative 6-, 12- and 36-mo survival rates were 94.9%, 86% and 86%, respectively. Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the presence of ascites (HR = 10.729, 95%CI: 1.209-95.183, P = 0.033) and elevated white blood cell count (HR = 1.072, 95%CI: 1.014-1.133, P = 0.015) were independent prognostic factors of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma. The cumulative 6-, 12- and 36-mo survival rates were significantly different between patients with and without ascites (90%, 61.5% and 61.5% vs 97.3%, 97.3% and 97.3%, respectively, P = 0.0008).

CONCLUSION: The presence of ascites and elevated white blood cell count were significantly associated with poor prognosis in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma.

Core tip: Little is known regarding the prognostic factors of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma. We conducted a retrospective single-center study of 64 patients admitted to our department between July 2002 and June 2010 to evaluate this issue. Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the presence of ascites was an independent prognostic factor of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma.

- Citation: Qi XS, Bai M, He CY, Yin ZX, Guo WG, Niu J, Wu FF, Han GH. Prognostic factors in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma: An 8-year retrospective single-center study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(42): 7447-7454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i42/7447.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i42.7447

Portal cavernoma, also known as cavernous transformation of the portal vein, is a rare entity, which is characterized by a tangle of tortuous hepatopetal collateral veins in the hilum[1]. It is traditionally considered a sequela of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) to compensate for the interrupted portal blood flow[2,3]. Current treatment strategies for portal cavernoma focus on the prevention and treatment of variceal hemorrhage, prevention of recurrent thrombosis, and treatment of symptomatic portal biliopathy[4-6]. Given the rarity of portal cavernoma, controlled studies are unavailable, and therapeutic options vary in different centers. Previous studies, in which malignancy and cirrhosis were not excluded, have revealed that the increased mortality in EHPVO patients is closely associated with advanced age, presence of malignancy and cirrhosis, high bilirubin and deterioration of liver function[7-9]. However, little information is known regarding the prognostic factors in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma due to its low morbidity and mortality.

We conducted a retrospective study to determine the predictors for survival of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma managed by a uniform therapeutic strategy at our center.

Between July 2002 and June 2010, all consecutive patients with a diagnosis of portal cavernoma without abdominal malignancy or liver cirrhosis who were admitted to our department were enrolled in this observational study[10-12], regardless of age. Baseline data were collected upon admission or referral. Regular blood tests, hepatic and renal function tests, prothrombin time, internationalized normalized ratio (INR), color Doppler ultrasound (CDUS), computed tomography (CT) and endoscopy were performed in all patients. Thrombotic risk factors of EHPVO, including JAK2 V617F mutation, CD55 and CD59 deficiencies, anti-cardiolipin IgG antibodies, and factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene G20210A mutation, were detected at our department after September 2009[13,14]. Additionally, we recorded the date of diagnosis of portal cavernoma at our own hospital or an outside facility. Follow-up data were obtained every six months through outpatient or phone conversations with the patient or his or her family members. The primary endpoint was death. Follow-up continued either until death or July 2010. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of our hospital.

Portal cavernoma was characterized by a tangle of tortuous hepatopetal collateral veins in the hilum. An acute thrombotic episode was defined as fulfillment of both of the following criteria: (1) recent onset of abdominal pain; and (2) a high intraluminal density within the portal vein on non-enhanced CT scans, while contrast-enhanced CT scans displayed cavernous vessels around the obstructed portal vein[15,16].

As previously described, the degree of portal venous obstruction was classified as partial obstruction, complete obstruction and fibrotic cord instead of original main portal vein[12,17,18]. The extent of obstruction within the portal venous system was also evaluated.

Liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma were excluded on the basis of a history of chronic liver disease, clinical presentation, liver function, alpha-fetoprotein and positive findings on imaging (i.e., ultrasound and CT scans)[18]. A liver biopsy was obtained, if a diagnosis of cirrhosis was inconclusive or if hepatocellular carcinoma was suspected. Other abdominal malignancy was excluded by imaging.

The degree of variceal size was based on the general rules established by the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension (low-risk varices: F1 or F2 with negative red color sign; high-risk: F1 or F2 with positive red color sign, or F3 irrespective of red color sign)[19]. The presence of ascites was diagnosed by physical examination, ultrasound and CT scans. The grade of ascites was based on the definitions of the International Ascites Club (grade I: mild ascites only detectable by ultrasound; grade II: moderate symmetrical abdominal distension; grade III: marked abdominal distension)[20].

Our therapeutic strategy was aimed at minimal invasiveness and maximal beneficial effects through symptom resolution.

After diagnosis of an acute thrombotic episode, the patients received a continuous intravenous infusion of unfractionated heparin followed by oral warfarin. Initially, heparin was regularly administered intravenously at a starting dose of 1000-1400 U/h for 5 d. Subsequently, oral warfarin was prescribed at the dosage of 2.5-5 mg/d for at least 6 mo and was adjusted to maintain the INR at a target of 2.5 (range 2.0-3.0)[21]. A three-day overlap between intravenous and oral anticoagulation was required. Life-long oral anticoagulants were prescribed to patients with thrombophilia. If abdominal pain was progressive, we either indirectly infused thrombolytic agents into the superior mesenteric artery or performed direct thrombolysis in the portal vein by a percutaneous transhepatic approach. If ischemic intestinal infarction was diagnosed, emergency bowel resection was performed.

Once acute variceal bleeding was diagnosed, medical or endoscopic therapy was adopted as the first-line treatment option. If active bleeding was uncontrolled or if repeated hospitalizations were necessary to control recurrent variceal bleeding, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) insertion was performed through a transjugular approach alone or in combination with a transhepatic or transsplenic approach, as previously described[12,18,22]. If a TIPS procedure failed or was refused, splenectomy and devascularization were considered.

Other symptomatic treatments included anticoagulation for prevention of recurrent thrombosis, diuretics and/or paracentesis plus albumin for grade II and III ascites, splenectomy for hypersplenism and massive splenomegaly and prophylactic endoscopic therapy for high-risk varices. Additionally, if patients presented with a long history of repeated gastrointestinal syndromes unresponsive to conservative therapies, the TIPS procedure was considered.

Quantitative data were reported as mean ± SE and were compared with the independent sample t test or one-way analysis of variance; qualitative data were reported as frequencies and were compared with the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Cumulative survival rates were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier curves and were compared with a log-rank test. Independent predictors of survival were identified using the Cox regression model. The covariates incorporated into the multivariate analysis were the variables that reached statistical significance (P < 0.05) in univariate analysis. Two-tailed P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were performed with SPSS 12.0 (Chicago, IL, United States).

A total of 64 patients diagnosed with portal cavernoma without liver cirrhosis or abdominal malignancy were enrolled in the study. Notably, 5 patients presented with cavernous collateral veins around a patent main portal vein[10]. Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Sex (female/male ) | 26/38 |

| Age at admission (yr) | 32.05 ± 2.00 |

| Age at first diagnosis of portal cavernoma ( ≤ 18 yr/> 18 yr) | 26/38 |

| History of portal cavernoma (yr) | 3.68 ± 0.78 |

| Clinical presentations | |

| Abdominal distension | 37 |

| Abdominal pain | 26 |

| Variceal bleeding | 29 |

| Degree of varices (high risk/low risk/no varices) | 6/12/1946 |

| Ascites | 20 |

| Degree of ascites (grade III/grade II/grade I/no ascites) | 3/1/16/44 |

| Hydrothorax | 10 |

| Laboratory tests | |

| RBC (1012/L) | 3.95 ± 0.11 |

| Hb (g/L) | 106.25 ± 4.00 |

| WBC (109/L) | 8.11 ± 1.03 |

| PLT (109/L) | 298.73 ± 33.67 |

| PT (s) | 14.14 ± 0.24 |

| INR | 1.15 ± 0.02 |

| ALT (U/L ) | 29.97 ± 3.31 |

| AST (U/L) | 30.28 ± 2.64 |

| ALP (U/L) | 107.21 ± 7.68 |

| GGT (U/L) | 41.16 ± 5.96 |

| ALB (g/L) | 38.25 ± 0.58 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 16.05 ± 1.32 |

| Serum Cr (μmol/L) | 70.65 ± 2.48 |

| Serum Na (mmol/L) | 139.54 ± 0.45 |

| Child-Pugh class (A/B/C) | 12/1/1951 |

| Child-Pugh score | 5.70 ± 0.13 |

| MELD score | 4.25 ± 0.53 |

| Location and degree of obstruction | |

| Main portal vein (patent/partial/complete/fibrotic cord) | 5/5/12/42 |

| Right portal vein obstruction | 49 |

| Left portal vein obstruction | 51 |

| Splenic vein obstruction and splenectomy | 39 |

| Superior mesenteric vein obstruction | 34 |

Thrombotic risk factors of EHPVO were detected in 33 patients. Among them, 11 had positive JAK2 V617F mutation, none had both CD55 and CD59 deficiencies, two had weakly positive anti-cardiolipin IgG antibodies, and none had positive factor V Leiden or prothrombin gene G20210A mutation. Previous history of infection before admission included colitis (n = 1), pelvic infection (n = 1), appendicitis (n = 1), intra-abdominal infection secondary to duodenal ulcer perforation (n = 1), umbilical cord infection (n = 2), megacolon disease of newborn (n = 1), bacterial dysentery (n = 1), and pancreatitis (n = 4). Previous history of abdominal surgery before admission included splenectomy and devascularization for variceal bleeding (n = 11), splenectomy for hypersplenism and/or splenomegaly (n = 8), splenectomy for traumatic spleen rupture (n = 1), partial splenic artery embolization for hypersplenism (n = 1), cholecystectomy (n = 4), surgical repair of peptic ulcer perforation (n = 1), total hysterectomy for hysteromyoma (n = 1), and cesarean delivery (n = 1). Notably, 7 and 13 patients underwent splenectomy before and after the diagnosis of portal cavernoma, respectively.

Compared to patients without variceal bleeding, those with variceal bleeding were younger at admission (37.54 ± 2.56 years in the non-bleeding group vs 25.41 ± 2.74 years in the bleeding group, P = 0.002) and had a longer history of portal cavernoma (1.86 ± 0.66 years in the non-bleeding group vs 5.89 ± 1.44 years in the bleeding group, P = 0.009). A fibrotic cord replacing the main portal vein was more frequently found on CT scans in patients with variceal bleeding than those without (27/29 vs 15/35, P < 0.001). In contrast, superior mesenteric vein obstruction was less frequently observed in patients with variceal bleeding than those without (11/29 vs 23/35, P = 0.027). No significant relationship between Child-Pugh score and variceal bleeding was observed (Table 2).

| Variables | Variceal bleeding (n= 29) | No variceal bleeding (n= 35) | Pvalue |

| Age at admission (yr) | 25.41 ± 2.74 | 37.54 ± 2.56 | 0.002 |

| Sex (female/male) | 14/15 | 12/23 | 0.257 |

| History of portal cavernoma (yr) | 5.89 ± 1.44 | 1.86 ± 0.66 | 0.009 |

| Abdominal distension (yes/no) | 11/18 | 26/9 | 0.003 |

| Abdominal pain (yes/no) | 3/26 | 23/12 | < 0.001 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 8/21 | 12/23 | 0.565 |

| Hydrothorax (yes/no) | 4/25 | 6/29 | 0.713 |

| Jaundice (yes/no) | 2/27 | 2/33 | 0.846 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 3.36 ± 0.12 | 4.44 ± 0.12 | < 0.001 |

| Hb (g/L) | 87.21 ± 4.60 | 122.03 ± 4.86 | < 0.001 |

| WBC (109/L) | 7.47 ± 1.82 | 8.65 ± 1.16 | 0.574 |

| PLT (109/L) | 317.07 ± 50.27 | 283.53 ± 45.84 | 0.624 |

| PT (s) | 14.08 ± 0.35 | 14.18 ± 0.34 | 0.838 |

| INR | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 0.946 |

| ALT (U/L ) | 26.38 ± 4.87 | 32.94 ± 4.51 | 0.327 |

| AST (U/L ) | 28.85 ± 4.28 | 30.93 ± 3.33 | 0.388 |

| AST/ALT | 1.23 ± 0.08 | 1.21 ± 0.11 | 0.874 |

| ALP (U/L ) | 115.98 ± 13.43 | 99.94 ± 8.57 | 0.302 |

| GGT (U/L ) | 31.69 ± 8.60 | 49.00 ± 8.12 | 0.150 |

| ALB (g/L ) | 37.23 ± 0.79 | 39.09 ± 0.82 | 0.111 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 15.54 ± 2.13 | 16.48 ± 1.66 | 0.724 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 7.07 ± 1.54 | 7.43 ± 0.98 | 0.838 |

| Serum Cr (μmol/L) | 70.17 ± 3.88 | 71.06 ± 3.26 | 0.860 |

| Serum Na (mmol/L) | 139.26 ± 0.55 | 139.77 ± 0.70 | 0.577 |

| Child-Pugh class (A/B/C) | 23/5/1 | 28/7/0 | 0.529 |

| Child-Pugh score | 5.69 ± 0.21 | 5.71 ± 0.18 | 0.928 |

| MELD score | 3.93 ± 0.88 | 4.51 ± 0.65 | 0.593 |

| Main portal vein (fibrotic cord/complete obstruction/partial obstruction/patency) | 27/0/1/1 | 15/12/3/4 | < 0.001 |

| Right portal vein (obstruction/patency) | 19/10 | 30/5 | 0.058 |

| Left portal vein (obstruction/patency) | 21/8 | 30/5 | 0.188 |

| Splenic vein (obstruction and splenectomy/patency) | 14/15 | 25/10 | 0.059 |

| Superior mesenteric vein (obstruction/patency) | 11/18 | 23/12 | 0.027 |

The white blood cell (WBC) count, prothrombin time and INR were significantly higher, and albumin and serum sodium were significantly lower in patients with ascites than in those without (Table 3). A higher Child-Pugh score was also present in patients with ascites than in those without (6.85 ± 0.26 vs 5.18 ± 0.07, P < 0.001). Additionally, superior mesenteric vein obstruction was more frequently observed in patients with ascites than in those without (15/20 vs 19/44, P = 0.027).

| Variables | Ascites (n= 20) | No ascites (n= 44) | Pvalue |

| Age at admission (yr) | 36.60 ± 3.99 | 29.98 ± 2.25 | 0.127 |

| Sex (female/male) | 7/13 | 19/25 | 0.537 |

| History of portal cavernoma (yr) | 2.38 ± 0.89 | 4.28 ± 1.06 | 0.264 |

| Variceal bleeding (yes/no) | 12/8 | 21/23 | 0.565 |

| Varices (high risk/low risk/no varices) | 32/3/9 | 14/3/3 | 0.545 |

| Abdominal distension (yes/no) | 17/3 | 20/24 | 0.003 |

| Abdominal pain (yes/no) | 9/11 | 17/27 | 0.631 |

| Hydrothorax (yes/no) | 10/10 | 0/44 | < 0.001 |

| Jaundice (yes/no) | 2/18 | 2/42 | 0.403 |

| RBC (1012/L) | 3.94 ± 0.21 | 3.96 ± 0.13 | 0.944 |

| Hb (g/L) | 104.60 ± 6.55 | 107.00 ± 5.04 | 0.783 |

| WBC (109/L) | 12.28 ± 2.83 | 6.22 ± 0.62 | 0.006 |

| PLT (109/L) | 275.45 ± 53.28 | 309.30 ± 42.86 | 0.645 |

| PT (s) | 15.08 ± 0.41 | 13.71 ± 0.28 | 0.007 |

| INR | 1.23 ± 0.03 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 0.006 |

| ALT (U/L) | 24.65 ± 3.36 | 32.39 ± 4.54 | 0.282 |

| AST (U/L) | 28.85 ± 4.28 | 30.93 ± 3.33 | 0.717 |

| AST/ALT | 1.33 ± 0.18 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 0.305 |

| ALP (U/L) | 103.55 ± 10.29 | 108.88 ± 10.21 | 0.751 |

| GGT (U/L) | 46.70 ± 10.00 | 38.64 ± 7.43 | 0.535 |

| ALB (g/L) | 35.17 ± 0.91 | 39.65 ± 0.64 | < 0.001 |

| TBIL (μmol/L) | 17.79 ± 2.92 | 15.27 ± 1.39 | 0.379 |

| DBIL (μmol/L) | 8.35 ± 1.57 | 6.78 ± 1.05 | 0.409 |

| Serum Cr (μmol/L) | 73.40 ± 5.16 | 69.40 ± 2.77 | 0.460 |

| Serum Na (mmol/L) | 138.01 ± 1.00 | 140.24 ± 0.45 | 0.021 |

| Child-Pugh class (A/B/C) | 8/11/1 | 43/1/0 | < 0.001 |

| Child-Pugh score | 6.85 ± 0.26 | 5.18 ± 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| MELD score | 5.60 ± 0.93 | 3.64 ± 0.63 | 0.086 |

| Main portal vein (obstruction/patency) | 18/2 | 40/3 | 0.908 |

| Right portal vein (obstruction/patency) | 15/5 | 34/10 | 0.842 |

| Left portal vein (obstruction/patency) | 16/4 | 35/9 | 0.967 |

| Splenic vein (obstruction and splenectomy/patency) | 11/9 | 28/16 | 0.512 |

| Superior mesenteric vein (obstruction/patency) | 15/5 | 19/25 | 0.018 |

Ten patients were diagnosed with acute thrombotic episodes. None presented with variceal bleeding, but four had high-risk varices detected by endoscopy. Mild ascites was found by CDUS in three patients. The main portal vein was completely (n = 9) or partially (n = 1) obstructed. After intravenous anticoagulation was administered for 2-5 d, abdominal pain was alleviated in 5 patients and aggravated in another 5 patients. For the 5 patients with improved abdominal pain, oral anticoagulation was continued. During follow-up, partial recanalization of the main portal vein was found in 1 patient, while the main portal vein became unidentifiable and was replaced by cavernous collateral vessels in the remaining 4 patients. One patient with high-risk varices experienced melena 2 wk after anticoagulation. Anticoagulants were discontinued in this patient and were not resumed. For the 5 patients with increased abdominal pain, thrombolytics were indirectly infused via the superior mesenteric artery in 3 patients and directly via the portal vein in two patients. Of the 3 patients who received indirect thrombolysis, one became asymptomatic, while the other 2 patients underwent intestinal resection for ischemic intestinal infarction. One of the 2 patients died of pulmonary embolism 5 d after surgery. Of the 2 patients receiving direct thrombolysis for 3-5 d, abdominal pain completely resolved. During follow-up, partial recanalization of the main portal vein was found in 2 patients, while the main portal vein was replaced by cavernous collateral vessels in the remaining 3 patients. No adverse events were recorded.

Twenty-nine patients presented with acute (n = 7) and recurrent variceal bleeding (n = 22). Of the patients with acute variceal bleeding, 5 received pharmacological treatment, 1 had emergency endoscopic sclerotherapy and one underwent embolization of the gastric varices via a percutaneous trans-splenic approach. Active bleeding was controlled in these patients. One patient died of massive variceal rebleeding 49 d after discharge. Of the patients with recurrent variceal bleeding, TIPS placement was attempted after admission and was technically successful in eight patients. Of the remaining 14 patients with TIPS failure, 13 experienced at least one episode of rebleeding within 6 mo, and 1 was lost to follow-up. Three of these 13 patients underwent splenectomy and devascularization, and 10 had repeated endoscopic treatments.

Additionally, TIPS procedures were attempted in 4 patients who presented with repeated episodes of abdominal distension over more than 4 years, and these were technically successful in three patients. After successful TIPS insertions, two patients with SMV thrombosis developed shunt occlusions, and one of them presented with variceal hemorrhage that was controlled by endoscopic sclerotherapy. The shunt was patent in another patient. Preoperatively, his spleen was palpably enlarged 10 cm below the left costal margin. The size of the spleen was reduced, but the spleen remained clinically palpable at 20 mo after surgery. After TIPS failure, one patient underwent splenectomy for splenomegaly (6 cm below the left costal margin) and hypersplenism (a low WBC count of 1520 cells/mm3 and a low platelet count of 32000/mm3).

After a mean follow-up of 18 ± 2.41 mo, a total of seven patients had died. Causes of death were pulmonary embolism (n = 1), acute leukemia (n = 1), massive esophageal variceal hemorrhage (n = 1), progressive liver failure (n = 2), multiple liver abscesses (n = 1) and accident (n = 1). Overall, 6-, 12- and 36-mo cumulative survival rates were 94.9%, 86% and 86%, respectively (Figure 1A). Cumulative 6-, 12- and 36-mo survival rates were similar between patients with and without variceal bleeding (92.8%, 80.2% and 80.2% vs 97.1%, 92.5% and 92.5%, respectively, P = 0.269, Log-rank test) (Figure 1B). Cumulative 6-, 12- and 36-mo survival rates were significantly different between patients with and without ascites (90%, 61.5% and 61.5% vs 97.3%, 97.3% and 97.3%, respectively, P = 0.0008, Log-rank test, Figure 1C).

Given that the risk factors of EHPVO were detected in only half of the patients, they were not included in the prognostic analysis. In the univariate analysis, variables that were significantly associated with reduced survival included the presence of ascites and hydrothorax, a low level of serum sodium, an elevated WBC count and a high Child-Pugh class (Table 4). Multivariate backward stepwise Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the presence of ascites (HR = 10.729, 95%CI: 1.209-95.183, P = 0.033) and an elevated WBC count (HR = 1.072, 95%CI: 1.014-1.133, P = 0.015) were independent predictors of increased mortality in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma.

| Variables | HR | 95%CI | Pvalue |

| Sex (female/male) | 0.559 | 0.108-2.883 | 0.487 |

| Age at admission | 1.032 | 0.984-1.083 | 0.194 |

| Age at first diagnosis ( ≤ 18 yr/> 18 yr) | 0.840 | 0.187-3.772 | 0.820 |

| History of portal cavernoma | 0.989 | 0.878-1.114 | 0.857 |

| Varices (yes/no) | 0.428 | 0.083-2.213 | 0.311 |

| Variceal bleeding (yes/no) | 2.450 | 0.475-12.653 | 0.285 |

| Abdominal distension (yes/no) | 2.253 | 0.435-11.657 | 0.333 |

| Abdominal pain (yes/no) | 2.010 | 0.450-8.989 | 0.361 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 15.066 | 1.811-125.337 | 0.012 |

| Hydrothorax (yes/no) | 6.638 | 1.452-30.346 | 0.015 |

| RBC | 0.681 | 0.288-1.614 | 0.383 |

| Hb | 0.987 | 0.964-1.011 | 0.302 |

| PLT | 1.000 | 0.997-1.003 | 0.900 |

| WBC | 1.099 | 1.040-1.162 | 0.001 |

| PT | 1.083 | 0.751-1.562 | 0.668 |

| INR | 5.253 | 0.057-480.003 | 0.471 |

| ALT | 0.970 | 0.915-1.029 | 0.312 |

| AST | 0.966 | 0.905-1.032 | 0.305 |

| AST/ALT | 2.328 | 0.891-6.083 | 0.085 |

| ALP | 1.003 | 0.993-1.013 | 0.558 |

| GGT | 1.003 | 0.989-1.017 | 0.684 |

| ALB | 0.932 | 0.795-1.094 | 0.392 |

| TBIL | 1.028 | 0.969-1.091 | 0.358 |

| DBIL | 1.036 | 0.941-1.140 | 0.470 |

| Serum Cr | 1.007 | 0.971-1.045 | 0.704 |

| Serum Na | 0.764 | 0.635-0.918 | 0.004 |

| Child-Pugh score | 1.573 | 0.976-2.535 | 0.063 |

| Child-Pugh class (class A/class B and C) | 0.083 | 0.009-0.763 | 0.028 |

| MELD score | 1.067 | 0.899-1.267 | 0.459 |

| TIPS insertion (failure/success) | 0.677 | 0.095-4.806 | 0.696 |

| Main portal vein (patency/obstruction) | 0.042 | 0.0001-1720.16 | 0.558 |

| Main portal vein (no fibrotic cord/fibrotic cord) | 0.798 | 0.155-4.113 | 0.787 |

| Right portal vein (patency/obstruction) | 2.269 | 0.507-10.151 | 0.284 |

| Left portal vein (patency/obstruction) | 1.639 | 0.318-8.455 | 0.555 |

| Splenic vein (patency/obstruction and splenectomy) | 0.533 | 0.103-2.766 | 0.454 |

| Superior mesenteric vein (patency/obstruction) | 0.159 | 0.019-1.330 | 0.090 |

This study was primarily designed to evaluate the outcome of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma and to determine prognostic factors. Our study demonstrated that most patients with portal cavernoma in the absence of cirrhosis or malignancy had a relatively benign course (overall cumulative survival rate was 86% at 60 mo), which is similar to the excellent outcomes of non-cirrhotic patients with portal vein or splanchnic vein thrombosis reported by previous studies[23-25]. However, it should be noted that all deaths occurred within the first year after admission, which is explained by the following points. First, a long history of portal cavernoma was recorded in some patients. It is possible that the underlying disease or liver dysfunction had already become severe in these patients, warranting referral to our highly specialized center. Second, as shown previously, the overall mortality of splanchnic vein thrombosis patients with intestinal infarction is high[23]. As a primary cause of death, intestinal infarction and its secondary severe complications often occur at the early stage. In our study, one of two patients who underwent bowel resection for intestinal infarction died 5 d after surgery.

Despite the high prevalence of variceal bleeding in our patients, the incidence of death was not significant (only one patient died of massive variceal bleeding), mainly due to advances in treatment modalities for controlling bleeding and well-preserved liver function in these patients. More importantly, we found that the presence of ascites might act as the most important prognostic factor for death. This finding could be explained by the higher incidence of liver dysfunction in patients with ascites. Indeed, the deterioration of liver function is caused not only by the presence of ascites itself, but also by a higher prothrombin time and INR and a lower level of serum albumin and sodium, which are closely correlated with the presence of ascites. Based on the prognostic significance of ascites in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma, therapeutic decision making needs to be further altered. Once ascites is detected, we should pay more attention to early diagnosis and treatment of underlying comorbidities and liver dysfunction. Accordingly, we hypothesize that the prevention and treatment of liver dysfunction should be incorporated into the treatment strategy for portal cavernoma[4].

We also found that an elevated WBC count was an independent predictor of survival. This might be explained by the fact that comorbidities, such as acute leukemia (n = 1) and multiple liver abscesses (n = 1) could be more common in patients with an elevated WBC count. However, it should be noted that the effect size was very small (hazard ratio was very close to 1). Therefore, the significance of WBC count on patient survival might be clinically slight.

Our study has several limitations. First, only patients diagnosed with portal cavernoma were included in this study. The inclusion criteria may influence the application of prognostic factors in patients with acute EHPVO. However, we believe that it was important to differentiate between the outcomes of acute EHPVO and portal cavernoma, because of their dissimilar clinical presentations and natural history. Second, the prevalence and significance of underlying etiological factors in patients with EHPVO are discussed elsewhere[13,14,26,27], but not in this study. Therefore, we can not demonstrate the association between survival and prothrombotic factors, including acquired and inherited factors. Further work is warranted to explore the effect of etiological factors on survival. Third, given the excellent outcome of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma, mean follow-up time was relatively short and a low proportion of patients met the endpoints in our study. This bias might miss other potential prognostic factors. An extended follow-up should be carried out in future studies. Fourth, the laboratory analysis of ascitic fluids was not performed. We could not exclude the possibility of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, especially in cases with an elevated WBC. Finally, given that the number of deaths was only 7, the multivariate Cox regression analysis might be inappropriate. Indeed, the number of variables included in the multivariate analysis might introduce the risk of overfitting the data, thereby leading to a high risk of false positive results. Therefore, the conclusions of this analysis should be taken with caution and further confirmed in larger studies.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the presence of ascites and an elevated WBC count are significantly associated with increased mortality in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma. Further studies are needed to confirm the prognostic significance of ascites in these patients and to establish a new therapeutic strategy based on the presence of ascites.

Portal cavernoma is traditionally considered a sequela of extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) to compensate for the interrupted portal blood flow. Due to its low morbidity and mortality in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients, little information is known regarding the prognostic factors of portal cavernoma.

Previous studies, in which malignancy and cirrhosis were not excluded, have revealed that the increased mortality in EHPVO patients is closely associated with advanced age, presence of malignancy and cirrhosis, high bilirubin and deterioration of liver function.

The authors conducted an 8-year retrospective single-center study to determine the predictors for survival of non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma managed by a uniform therapeutic strategy at our center.

The authors found that the presence of ascites might act as the most important prognostic factor for death in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma. Based on the prognostic significance of ascites in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma, therapeutic decision making needs to be further altered.

Portal cavernoma, also known as cavernous transformation of the portal vein, is a rare entity, which is characterized by a tangle of tortuous hepatopetal collateral veins in the hilum.

It is an interesting review of portal cavernoma evolution. In this study, the authors investigated the prognostic factors for portal cavernoma in non-malignant and non-cirrhotic patients. They were able to show that the presence of ascites and an elevated white blood cell count were strongly associated with poor prognosis in non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma.

P- Reviewers: Castellote J, Raziorrouh B S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Ohnishi K, Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Nakayama T, Hiyama Y, Iwama S, Goto N, Nakajima Y, Musha N, Nakashima T. Formation of hilar collaterals or cavernous transformation after portal vein obstruction by hepatocellular carcinoma. Observations in ten patients. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1150-1153. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Valla DC, Condat B. Portal vein thrombosis in adults: pathophysiology, pathogenesis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;32:865-871. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Campanale C, Rinninella E, Tortora A, Di Maurizio L, Bombardieri G, De Cristofaro R, De Gaetano AM, Landolfi R. Portal vein thrombosis: insight into physiopathology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:143-155. [PubMed] |

| 4. | DeLeve LD, Valla DC, Garcia-Tsao G. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology. 2009;49:1729-1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 40.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [PubMed] |

| 6. | De Stefano V, Martinelli I. Splanchnic vein thrombosis: clinical presentation, risk factors and treatment. Intern Emerg Med. 2010;5:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rajani R, Björnsson E, Bergquist A, Danielsson A, Gustavsson A, Grip O, Melin T, Sangfelt P, Wallerstedt S, Almer S. The epidemiology and clinical features of portal vein thrombosis: a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1154-1162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Janssen HL, Wijnhoud A, Haagsma EB, van Uum SH, van Nieuwkerk CM, Adang RP, Chamuleau RA, van Hattum J, Vleggaar FP, Hansen BE. Extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis: aetiology and determinants of survival. Gut. 2001;49:720-724. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Orr DW, Harrison PM, Devlin J, Karani JB, Kane PA, Heaton ND, O’Grady JG, Heneghan MA. Chronic mesenteric venous thrombosis: evaluation and determinants of survival during long-term follow-up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:80-86. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Qi X, Han G, Yin Z, He C, Guo W, Niu J, Wu K, Fan D. Cavernous vessels around a patent portal trunk in the liver hilum. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qi X, Han G, Yin Z, He C, Bai M, Yang Z, Guo W, Niu J, Wu K, Fan D. A large portal vein: a rare finding of recent portal vein thrombosis. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011;5:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Qi X, Han G, Yin Z, He C, Wang J, Guo W, Niu J, Zhang W, Bai M, Fan D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal cavernoma with symptomatic portal hypertension in non-cirrhotic patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1072-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Qi X, He C, Han G, Yin Z, Wu F, Zhang Q, Niu J, Wu K, Fan D. Prevalence of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in Chinese patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome or portal vein thrombosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Qi X, Zhang C, Han G, Zhang W, He C, Yin Z, Liu Z, Bai W, Li R, Bai M. Prevalence of the JAK2V617F mutation in Chinese patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis: a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1036-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Qi X, Han G, He C, Yin Z, Guo W, Niu J, Fan D. CT features of non-malignant portal vein thrombosis: a pictorial review. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36:561-568. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Qi X, Han G, Bai M, Fan D. Stage of portal vein thrombosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:1080-102; author reply 1080-102. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Qi X, Han G, Wang J, Wu K, Fan D. Degree of portal vein thrombosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1089-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Han G, Qi X, He C, Yin Z, Wang J, Xia J, Yang Z, Bai M, Meng X, Niu J. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis with symptomatic portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:78-88. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Idezuki Y. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (1991). Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension. World J Surg. 1995;19:420-422; discussion 423. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, Angeli P, Porayko M, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 611] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Qi X, Han G, Wu K, Fan D. Anticoagulation for portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. Am J Med. 2010;123:e19-20; author reply e21. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Qi X, Han G. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of portal vein thrombosis: a critical review of literature. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:576-590. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Scaglione M, Pezzullo L, Sangiuliano N, Armellino MF, Manguso F, Margaglione M, Ames PR, Iannaccone L. Prognostic factors in noncirrhotic patients with splanchnic vein thromboses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2464-2470. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Webb LJ, Sherlock S. The aetiology, presentation and natural history of extra-hepatic portal venous obstruction. Q J Med. 1979;48:627-639. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Spaander MC, van Buuren HR, Hansen BE, Janssen HL. Ascites in patients with noncirrhotic nonmalignant extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:529-534. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Qi X, De Stefano V, Wang J, Bai M, Yang Z, Han G, Fan D. Prevalence of inherited antithrombin, protein C, and protein S deficiencies in portal vein system thrombosis and Budd-Chiari syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:432-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Qi X, Yang Z, Bai M, Shi X, Han G, Fan D. Meta-analysis: the significance of screening for JAK2V617F mutation in Budd-Chiari syndrome and portal venous system thrombosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1087-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |