Published online Oct 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6472

Revised: August 13, 2013

Accepted: August 28, 2013

Published online: October 14, 2013

Processing time: 134 Days and 23.7 Hours

AIM: To assess midterm results of stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) and predictive factors for outcome.

METHODS: From May 2007 to May 2009, 75 female patients underwent STARR and were included in the present study. Preoperative and postoperative workup consisted of standardized interview and physical examination including proctoscopy, colonoscopy, anorectal manometry, and defecography. Clinical and functional results were assessed by standardized questionnaires for the assessment of constipation constipation scoring system (CSS), Longo’s ODS score, and symptom severity score (SSS), incontinence Wexner incontinence score (WS), quality of life Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAC-QOL), and patient satisfaction visual analog scale (VAS). Data were collected prospectively at baseline, 12 and 30 mo.

RESULTS: The median follow-up was 30 mo (range, 30-46 mo). Late postoperative complications occurred in 11 (14.7%) patients. Three of these patients required procedure-related reintervention (one diverticulectomy and two excision of staple granuloma). Although the recurrence rate was 10.7%, constipation scores (CSS, ODS score and SSS) significantly improved after STARR (P < 0.0001). Significant reduction in ODS symptoms was matched by an improvement in the PAC-QOL and VAS (P < 0.0001), and the satisfaction index was excellent in 25 (33.3%) patients, good in 23 (30.7%), fairly good in 14 (18.7%), and poor in 13 (17.3%). Nevertheless, the WS increased after STARR (P = 0.0169). Incontinence was present or deteriorated in 8 (10.7%) patients; 6 (8%) of whom were new onsets. Univariate analysis revealed that the occurrence of fecal incontinence (preoperative, postoperative or new-onset incontinence; P = 0.028, 0.000, and 0.007, respectively) was associated with the success of the operation.

CONCLUSION: STARR is an acceptable procedure for the surgical correction of ODS. However, its impact on symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence may be problematic.

Core tip: As a less-invasive surgical procedure, stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) is becoming an important option in the treatment of obstructive defecation syndrome. However, its clinical and functional outcomes are still conflicting and controversial. The present study assessed the midterm results after STARR performed by the same team in our department to identify factors for predicting outcome. Our data provide evidence to attest the clinic benefits of this procedure, but its impact on symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence may be problematic.

- Citation: Zhang B, Ding JH, Zhao YJ, Zhang M, Yin SH, Feng YY, Zhao K. Midterm outcome of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome: A single-institution experience in China. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(38): 6472-6478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i38/6472.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6472

Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) is defined as the normal desire to defecate but with an impaired ability to evacuate the rectum satisfactorily[1]. The anatomical and physiological disturbances underlying ODS are complex and only partly understood, but rectocele and intussusception have been identified as the two most important organic causes of ODS[2].

Although a variety of surgical approaches has been described in the literature for correction of ODS, most of these have high recurrence and complication rates. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) was introduced in 2003 by Longo[3] as a minimally invasive transanal operation for ODS associated with rectocele and intussusception. The novel procedure is carried out using double circular stapler devices to resect a full-thickness segment of rectal wall and subsequently to restore normal rectal anatomy. In contrast to traditional techniques, STARR addresses correction of both rectocele and intussusception.

Several multicenter trials have demonstrated that STARR significantly improves constipation with low morbidity and high comfort for patients[4-8]. In addition, the procedure could even offer long-term clinical benefits[9-11]. Nevertheless, worrisome complications and unsatisfactory functional results have been described[12,13]. There are also reports of high rates of reintervention for both symptomatic recurrence and procedure-related complications after this surgery[14,15]. As a consequence, although STARR is increasingly being accepted as an important option for surgical treatment of ODS, its clinical and functional outcomes are still conflicting and controversial.

We have shown previously that STARR can be performed safely and is effective for eligible patients with ODS secondary to rectocele and intussusceptions[16,17]. The objective of this study was to assess midterm clinical and functional results and to identify factors for predicting outcome after STARR.

From May 2007 to May 2009, a consecutive series of 86 female patients was treated with STARR for ODS in our Department of Colorectal Surgery at the Second Artillery General Hospital, Beijing, China. A total of 75 (87.2%) patients completed the scheduled follow-up and formed the study population. All patients were prospectively included in a database. Study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee of our hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study. Preoperative assessment included symptom evaluation, clinical and gynecological examinations, and investigations with proctoscopy, colonoscopy, colonic transit time study, anorectal manometry, and defecography. Anorectal manometry was performed as previously described[17]. Patients were carefully selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria for STARR proposed by the consensus recommendations[18] and the decision-making algorithm[2].

Polyethylene glycol electrolyte solutions were preoperatively prescribed for bowel preparation. Patients received routine broad-spectrum antibiotics immediately after anesthesia induction. Under spinal anesthesia, patients were placed in the lithotomy position with a catheter in the bladder. The STARR procedure was performed using the circular stapler (PPH-01; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., New Brunswick, NJ, United States) as described previously[4]. Subsequent bleeding from the staple line was controlled with full-thickness 2-0 Vicryl stitches (Ethicon Endo-Surgery). All STARR procedures were conducted by the same surgical team.

The severity of ODS was quantified by the validated constipation scoring system (CSS; range: 0-30 at increments of 1; no symptoms = 0)[19]; Longo’s ODS score (range: 0-40 at increments of 1; no symptoms = 0)[16]; and symptom severity score (SSS; range: 0-36 at increments of 1; no symptoms = 0)[7]. Patient’s fecal incontinence was assessed by the Wexner incontinence score (WS; range: 0-36 at increments of 1; perfect continence = 0)[20]. The validated Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life Questionnaire (PAC-QOL) was used to measure the quality of life in patients with ODS[21]. The first three subscales of the self-reported questionnaire were used to assess the patient dissatisfaction index, with an overall score ranging from 0 to 96 (lower scores corresponding to better quality of life). The satisfaction subscale included four items with a global score ranging from 0 to 16 (high scores corresponding to better quality of life)[22]. Moreover, the index of patient satisfaction was also measured by the visual analog scale (VAS) with scores from 0 to 10, and a higher score suggested an improvement in patient satisfaction with surgery.

The patients were followed up in our clinic at 3, 6, 12 and 30 mo postoperatively. At each visit, digital rectal examination was used to assess the anal sphincter, and proctoscopy or colonoscopy to evaluate the anastomosis and the presence or absence of local complications (stenosis, granulomas or mucosal prolapse). We also recorded the occurrence of postoperative complications, which were considered to be early if they occurred within 1 mo after surgery and late if they occurred after this period. A complete clinical reassessment including anorectal manometry and defecography was performed at 12 mo after surgery. Functional results were further updated at 30 mo of follow-up using the same standardized questionnaires (CSS, ODS score, SSS, WS, PAC-QOL and VAS). The STARR procedure was considered successful at 30 mo when PAC-QOL (satisfaction index) scores were classified as excellent, good, or fairly good, defined as follows: 13-16 classified as excellent, 9-12 as good, 5-8 as fairly good, and 0-4 as poor.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows XP (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, United States). The variation of total scores of the CSS, ODS, SSS, WS, PAC-QoL and VAS were expressed as mean values with 95%CI. Data were compared between groups using the two-sample t test, paired t test, Pearson’s χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, and Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as indicated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of the 75 female patients (mean age, 54.3 years; range, 29-75 years) included in this study, 60 (80%) had experienced vaginal delivery and 31 (41.3%) were multiparous. Sixty-four (61.3%) patients underwent previous anorectal/gynecological surgery, including episiotomy (18 patients), hemorrhoidectomy (14 patients), fistulectomy (3 patients), sphincterotomy (1 patient), and hysterectomy (10 patients). Defecographic and manometric findings are detailed in Table 1.

| Factors | Total (n = 75) | Successful (n = 62) | Unsuccessful (n = 13) | P value |

| Mean age (yr)1 | 54.30 | 53.80 | 56.50 | 0.287 |

| Multiparous/non-multiparous2 | 31/44 | 24/38 | 7/6 | 0.314 |

| Hysterectomy/no hysterectomy3 | 10/65 | 7/55 | 3/10 | 0.364 |

| Anorectal operation before STARR/no operation2 | 36/39 | 29/33 | 7/6 | 0.643 |

| Constipation scores1 | ||||

| CSS score | 15.57 | 15.60 | 15.46 | 0.569 |

| ODS score | 18.39 | 18.03 | 20.08 | 0.994 |

| SSS score | 13.69 | 13.55 | 14.38 | 0.537 |

| Manometric parameters1 | ||||

| Resting pressure (mmHg) | 54.13 | 54.27 | 53.46 | 0.497 |

| Squeeze pressure (mmHg) | 109.0 | 109.5 | 106.7 | 0.726 |

| First initial sensation (mL) | 87.05 | 86.53 | 89.54 | 0.649 |

| Maximum tolerable rectal volume (mL) | 238.2 | 238.2 | 238.0 | 0.248 |

| Defecographic parameters | ||||

| Rectocele (mm)1 | 35.12 | 34.62 | 37.46 | 0.220 |

| Intussuception/no intussuception3 | 65/10 | 56/6 | 9/4 | 0.064 |

| Increased perineal descent/no perineal descent3 | 21/54 | 15/47 | 6/7 | 0.171 |

| Sigmoidocele/no sigmoidocele3 | 9/66 | 7/55 | 2/11 | 0.650 |

| Fecal incontinence3 | ||||

| Preoperative incontinence/no incontinence | 2/73 | 0/62 | 2/11 | 0.028 |

| Postoperative incontinence/no incontinence | 8/67 | 2/60 | 6/7 | 0.000 |

| New-onset incontinence/no incontinence | 6/69 | 2/60 | 4/9 | 0.007 |

A staple-line dehiscence necessitating handsewn suturing was the only intraoperative complication that we observed. There were no major complications, rectovaginal fistula, pelvic sepsis, or deaths. The operative data, early postoperative complications, and short-term results were described in our previous studies[16,17].

A total of 12 late complications occurred in 11 patients, giving an overall morbidity rate of 14.7%. The most frequently reported complication was postoperative incontinence, which was present or deteriorated in eight (10.7%) patients. Although defecatory urgency vanished spontaneously in most patients within the first 3 mo postoperatively, one (1.3%) patient reported this complaint at the time of the latest interview. Two (2.7%) patients suffered from inflammatory granulomas on the staple line, which had to be removed because of chronic pain or bleeding. Additionally, there was one (1.3%) case of iatrogenic rectal diverticulum with impacted fecalith confirmed 34 mo after surgery. It presented as severe recurrence of obstructed defecation and was treated by transanal diverticulectomy[23]. Thus, 3 (4%) patients required transanal reintervention for procedure-related complications after STARR.

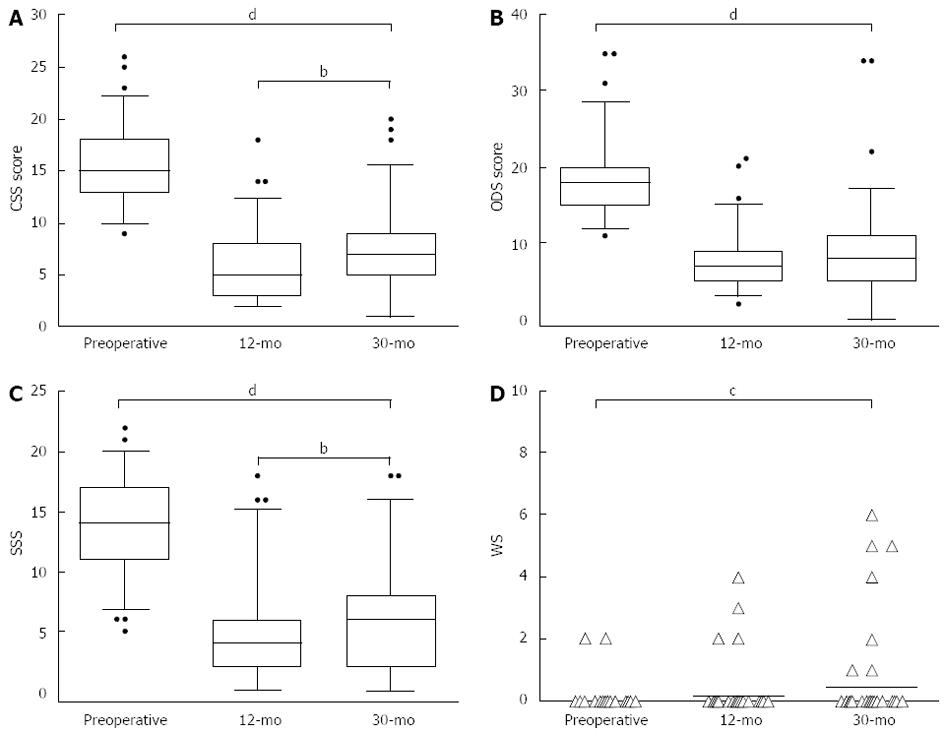

Changes in the constipation scores (CSS, ODS score and SSS) and the incontinence scores (WS) are presented in Figure 1. Globally, a significant reduction in the CSS, ODS score and SSS was observed at 12 mo as compared with baseline, and this reduction was maintained at 30 mo [CSS at baseline vs 30 mo: 15.57 (95%CI: 14.78-16.36) vs 7.07 (95%CI: 6.16-7.98); ODS score: 18.39 (95%CI: 17.27-19.51) vs 8.55 (95%CI: 7.12-9.97); SSS: 13.69 (95%CI: 12.74-14.64) vs 6.16 (95%CI: 5.12-7.20); P < 0.0001 in each group]. However, these scores started to increase slightly after 12 mo [CSS at 12 mo vs 30 mo: 5.99 (95%CI: 5.28-6.70) vs 7.07 (95%CI: 6.16-7.98); SSS: 4.59 (95%CI: 3.73-5.45) vs 6.16 (95%CI: 5.12-7.20), P < 0.01; ODS score: 7.49 (95%CI: 6.65-8.34) vs 8.55 (95%CI: 7.12-9.97), P = 0.07]. Overall, the symptoms of ODS had persisted or recurred in 8 (10.7%) patients with adequate follow-up. Two patients who had initial improvement presented with persistence of ODS symptoms 3 mo after surgery, and another 6 patients developed symptomatic recurrence after 12 mo.

Although the WS rose slightly after STARR, two cases of new-onset fecal incontinence and two of worsened incontinence were observed during 12 mo follow-up, there was no significant difference before and after surgery [WS at baseline vs at 12 mo: 0.05 (95%CI: -0.02-0.13) vs 0.15 (95%CI: -0.003-0.30), P = 0.052]. However, another four patients had new-onset incontinence after 12 mo and the WS increased significantly at 30 mo follow-up [WS at baseline vs at 30 mo: 0.05 (95%CI: -0.02-0.13) vs 0.43 (95%CI: 0.09-0.76), P = 0.017]. On the whole, incontinence was present or deteriorated in 8 (10.7%) patients, 6 (8%) of whom had new onset.

As shown in Table 2, improvement in the constipation scores was matched by an overall improvement in quality of life as assessed by the PAC-QOL and VAS scores at both 12 and 30 mo follow-up [PAC-QOL (dissatisfaction index) at baseline vs 30 mo: 44.45 (95%CI: 41.15-47.76) vs 13.21 (95%CI: 10.36-16.07); PAC-QOL (satisfaction index): 0 vs 10.12 (95%CI: 9.21-11.03); VAS: 3.83 (95%CI: 3.54-4.11) vs 7.07 (95%CI: 6.69-7.46); P < 0.0001]. At the end of follow-up, the self-reported definitive outcome was reported as excellent by 25 (33.3%) patients, good by 23 (30.7%), fairly good by 14 (18.7%), and poor by 13 (17.3%). Symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence were the main reasons for a poorer outcome.

In accordance with the patient’s assessment of the clinical outcome at 30 mo follow-up, 17 patient- and disease-related factors were used to compare 65 patients who acquired any improvement after STARR with 13 patients who considered an absence of success for further statistical analyses (Table 1). The result of the univariate analysis revealed that lack of improvement was more likely in patients with fecal incontinence (preoperative, postoperative or new-onset incontinence; P = 0.028, 0.000, and 0.007, respectively). However, multiparous, hysterectomy, previous anorectal operation, CSS, ODS score, SSS, and defecographic or manometric findings were not correlated with the functional success of the operation.

Controversy exists in the literature regarding the results after STARR, therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the midterm results and predictive factors for outcome. We assessed a series of 75 patients before and 30 mo after STARR, in which late postoperative complications were seen in 14.7% and reintervention was required in 4%. Despite the recurrence rate of 10.7%, clinical and functional outcome scores (CSS, ODS, SSS, PAC-QOL, and VAS) significantly improved after surgery. Nevertheless, the significant reduction in ODS symptoms was not matched by impairment of the WS. The success of the STARR procedure was associated with the occurrence of fecal incontinence, which was present or deteriorated in 10.7% of patients after surgery.

Several studies have indicated the midterm efficacy of STARR in relieving ODS symptoms with high patient satisfaction rates[4,5,24-27]. Similar clinic benefits were obtained in the present study; we were able to demonstrate that defecation difficulties were significantly improved after STARR. Improvement remained stable at 30 mo follow-up as compared with baseline, albeit the constipation scores started increase 12 mo after surgery. Meanwhile, the satisfaction index was reported as excellent in 25 (33.3%), good in 23 (30.7%), fairly good in 14 (18.7%), and poor in 13 (17.3%). Hence, our midterm follow-up suggests that early postoperative benefits were maintained. Other reports, however, showed that ODS symptoms may not improve or even deteriorate after STARR[13,14]. The main reason for these conflicting observations may be the patient selection criteria. Inadequate indications for this operation will necessarily result in poor outcome. The outcomes of an Italian multicenter study were worse in none-selected patients and improvement after STARR was noted in only 65% of the patients[14]. In our series, all patients were carefully selected on the basis of the consensus recommendations and the decision-making algorithm[2,18], but further observations should evaluate whether the midterm efficacy deteriorates with time.

Although STARR produced good midterm results, eight (10.7%) patients in our study presented with persistent or recurrent symptoms of ODS. In the literature, the incidence of midterm recurrences is between 4.3% and 17.1%[5,8,14,28]. More recently, however, it has been shown that none of the patients who underwent STARR by the curved Contour Transtar stapler had recurrence of ODS symptoms during a 36-mo follow-up[29]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the limited capacity of PPH-01 casing with risk of leaving residual disease, especially in patients with large rectocele and intussusception. It should also be stressed that rectocele and intussusception are only the emerging tip of the ODS iceberg syndrome; pelvic floor pathology caused by the “underwater rocks” or occult lesions are likely to persist and contribute to persistent or recurrent symptoms after surgery[30].

Some series therefore have been designed to define predictive factors for outcomes after STARR. Gagliardi et al[14] have suggested that the results were worse in patients with preoperative digitation, puborectalis dyssynergia, enterocele, larger rectocele, lower bowel frequency, and sense of incomplete evacuation. Contrary to this observation, a subsequent study showed that the number of pelvic floor changes was associated with the success of the operation[11]. Another study demonstrated that factors for an unfavorable outcome after STARR included small rectal diameter, low sphincter pressure, and increased pelvic floor descent[8]. In the present study, we only indicated that the occurrence of fecal incontinence, including preoperative, postoperative or new-onset incontinence, was associated with poorer midterm outcome. In addition, postoperative incontinence was one of the main reasons for patient dissatisfaction. No doubt more evidence is needed to clarify this issue.

Fecal incontinence after STARR is one of the main concerns of surgeons. Postoperative incontinence and urgency have been reported as being transient and disappeared within 6 mo[4], but were still present after 30 mo in some of our patients. Incontinence may be caused by reduced rectal volume or by muscle stretching and transient sphincter dysfunction secondary to the 36-mm dilator[4,31]. We did not systematically evaluate the anal sphincter using ultrasound, but there was no evidence of sphincter dysfunction according to our manometry results. Intriguingly, 6 (8%) patients in our study had new-onset incontinence after the STARR procedure. A possible explanation is that intussuception in the anal canal may function as a barrier with a subsequently beneficial effect on fecal continence. After its removal, fecal incontinence becomes uncovered[31]. Consequently, a careful patient selection with the awareness of occult incontinence is crucial. It is noteworthy that incontinence improves in some patients, which is attributed to improved internal sphincter function after STARR[6,7,25,28]. Few patients with preoperative incontinence were enrolled, thus, it could not be assessed in our study.

In the current study, STARR was confirmed as a safe procedure for the treatment of ODS. Nevertheless, an unexpected major complication was observed in one patient who developed an iatrogenic rectal diverticulum after STARR. Concordant with previous findings[12,32], the diverticulum was located along the lateral wall of the rectum, an area of weakness, where anterior and posterior suture lines cross over one another. Iatrogenic diverticulum may also occur as a consequence of technical failure in that the lateral part of the rectal wall remained outside the staple casing during the second resection, or an incomplete section of the mucosal band was retained after STARR[32]. To the best of our knowledge, no patient has developed rectal diverticulum after Transtar for the surgical correction of ODS; therefore, this major complication may be the inherent drawbacks of the PPH-01 stapler that could be avoided by using the new device.

We conclude that STARR may be an acceptable procedure for the treatment of patients with ODS caused by rectocele and intussusception, but its impact on symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence may be problematic. In this study, patients were strictly selected and systematically assessed prospectively. However, there were still some limitations such as the lack of a control group. Moreover, postoperative defecography or magnetic resonance imaging with longer follow-up is also crucial for providing more details on pelvic floor anatomy as well as physiology. Finally, this was a midterm follow-up study. Further studies are needed to assess long-term results and to optimize patient selection, which is required to enhance and maintain patient satisfaction after surgery.

Obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) is a frequent but multifactorial disease that usually afflicts middle-aged women. Although a variety of surgical procedures has been proposed to correct ODS, no one has found unanimous consensus. Stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) was recently introduced as a minimally invasive transanal procedure, the advantage of which is the simultaneous treatment of rectocele and rectal intussusception, both representing the main anatomical cause of ODS.

In recent years, STARR is increasingly being accepted as an important option for surgical treatment of ODS. However, the clinical and functional outcomes after STARR are still conflicting and controversial. In the area of treatment of ODS by the STARR procedure, the research hotspots are how to optimize patient selection and to predict the functional outcome after surgery.

The authors assessed midterm results and predictive factors for outcome after STARR. Even though the recurrence rate was 10.7%, the clinical and functional outcome scores significantly improved after surgery. In addition, symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence were the main reasons for a poorer outcome.

The study results suggest that STARR may be an acceptable procedure for the treatment of ODS, but its impact on symptomatic recurrence and postoperative incontinence may be problematic.

This study assessed the midterm outcome of STARR for ODS. This topic has been previously studied, and the results of several studies have been discordant. Nevertheless, the topic is interesting for the readers of the journal and suitable to be published.

P- Reviewer Trifan A S- Editor Qi Y L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Andromanakos N, Skandalakis P, Troupis T, Filippou D. Constipation of anorectal outlet obstruction: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:638-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schwandner O, Stuto A, Jayne D, Lenisa L, Pigot F, Tuech JJ, Scherer R, Nugent K, Corbisier F, Basany EE. Decision-making algorithm for the STARR procedure in obstructed defecation syndrome: position statement of the group of STARR Pioneers. Surg Innov. 2008;15:105-109. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Longo A. Obstructed defecation because of rectal pathologies. Novel surgical treatment: stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR). Annual Cleveland Clinic Florida colorectal disease symposium; 2004; . |

| 4. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Stuto A, Bottini C, Caviglia A, Carriero A, Mascagni D, Mauri R, Sofo L, Landolfi V. Stapled transanal rectal resection for outlet obstruction: a prospective, multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1285-196; discussion 1285-196;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arroyo A, González-Argenté FX, García-Domingo M, Espin-Basany E, De-la-Portilla F, Pérez-Vicente F, Calpena R. Prospective multicentre clinical trial of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructive defaecation syndrome. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1521-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jayne DG, Schwandner O, Stuto A. Stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome: one-year results of the European STARR Registry. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1205-112; discussion 1205-112;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schwandner O, Fürst A. Assessing the safety, effectiveness, and quality of life after the STARR procedure for obstructed defecation: results of the German STARR registry. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:505-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Boenicke L, Reibetanz J, Kim M, Schlegel N, Germer CT, Isbert C. Predictive factors for postoperative constipation and continence after stapled transanal rectal resection. Br J Surg. 2012;99:416-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zehler O, Vashist YK, Bogoevski D, Bockhorn M, Yekebas EF, Izbicki JR, Kutup A. Quo vadis STARR? A prospective long-term follow-up of stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1349-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ommer A, Rolfs TM, Walz MK. Long-term results of stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for obstructive defecation syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1287-1292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Köhler K, Stelzner S, Hellmich G, Lehmann D, Jackisch T, Fankhänel B, Witzigmann H. Results in the long-term course after stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR). Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:771-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pescatori M, Gagliardi G. Postoperative complications after procedure for prolapsed hemorrhoids (PPH) and stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedures. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:7-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Madbouly KM, Abbas KS, Hussein AM. Disappointing long-term outcomes after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. World J Surg. 2010;34:2191-2196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gagliardi G, Pescatori M, Altomare DF, Binda GA, Bottini C, Dodi G, Filingeri V, Milito G, Rinaldi M, Romano G. Results, outcome predictors, and complications after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:186-195; discussion 195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pescatori M, Zbar AP. Reinterventions after complicated or failed STARR procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang B, Ding JH, Yin SH, Zhang M, Zhao K. Stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome associated with rectocele and rectal intussusception. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2542-2548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ding JH, Zhang B, Bi LX, Yin SH, Zhao K. Functional and morphologic outcome after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Corman ML, Carriero A, Hager T, Herold A, Jayne DG, Lehur PA, Lomanto D, Longo A, Mellgren AF, Nicholls J. Consensus conference on the stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for disordered defaecation. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 1967] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D, McDermott A, Chassany O. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:540-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Reboa G, Gipponi M, Ligorio M, Marino P, Lantieri F. The impact of stapled transanal rectal resection on anorectal function in patients with obstructed defecation syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1598-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhang B, Ding JH, Zhang M, Yin SH, Zhao YJ, Zhao K. Iatrogenic Rectal Diverticulum After Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection. J Med Cases. 2012;3:312-314. |

| 24. | Frascio M, Stabilini C, Ricci B, Marino P, Fornaro R, De Salvo L, Mandolfino F, Lazzara F, Gianetta E. Stapled transanal rectal resection for outlet obstruction syndrome: results and follow-up. World J Surg. 2008;32:1110-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Titu LV, Riyad K, Carter H, Dixon AR. Stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation: a cautionary tale. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1716-1722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Patel CB, Ragupathi M, Bhoot NH, Pickron TB, Haas EM. Patient satisfaction and symptomatic outcomes following stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation syndrome. J Surg Res. 2011;165:e15-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Song KH, Lee du S, Shin JK, Lee SJ, Lee JB, Yook EG, Lee DH, Kim do S. Clinical outcomes of stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS): a single institution experience in South Korea. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Goede AC, Glancy D, Carter H, Mills A, Mabey K, Dixon AR. Medium-term results of stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) for obstructed defecation and symptomatic rectal-anal intussusception. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1052-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Roviaro G. What is the benefit of a new stapler device in the surgical treatment of obstructed defecation? Three-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pescatori M, Spyrou M, Pulvirenti d’Urso A. A prospective evaluation of occult disorders in obstructed defecation using the ‘iceberg diagram’. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lang RA, Buhmann S, Lautenschlager C, Müller MH, Lienemann A, Jauch KW, Kreis ME. Stapled transanal rectal resection for symptomatic intussusception: morphological and functional outcome. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1969-1975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Frascio M, Lazzara F, Stabilini C, Fornaro R, De Salvo L, Mandolfino F, Ricci B, Gianetta E. Pseudodiverticular defecographic image after STARR procedure for outlet obstruction syndrome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1115-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |