Published online Oct 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6408

Revised: March 26, 2013

Accepted: May 9, 2013

Published online: October 14, 2013

Processing time: 305 Days and 7.5 Hours

AIM: To assess the esophageal motility in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and to compare those with patients with autoimmune disorders.

METHODS: 15 patients with IBS, 22 with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 19 with systemic sclerosis (SSc) were prospectively selected from a total of 115 patients at a single university centre and esophageal motility was analysed using standard manometry (Mui Scientific PIP-4-8SS). All patients underwent esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy before entering the study so that only patients with normal endoscopic findings were included in the current study. All patients underwent a complete physical, blood biochemistry and urinary examination. The grade of dysphagia was determined for each patient in accordance to the intensity and frequency of the presented esophageal symptoms. Furthermore, disease activity scores (SLEDAI and modified Rodnan score) were obtained for patients with autoimmune diseases. Outcome parameter: A correlation coefficient was calculated between amplitudes, velocity and duration of the peristaltic waves throughout esophagus and patients’ dysphagia for all three groups.

RESULTS: There was no statistical difference in the standard blood biochemistry and urinary analysis in all three groups. Patients with IBS showed similar pathologic dysphagia scores compared to patients with SLE and SSc. The mean value of dysphagia score was in IBS group 7.3, in SLE group 6.73 and in SSc group 7.56 with a P-value > 0.05. However, the manometric patterns were different. IBS patients showed during esophageal manometry peristaltic amplitudes at the proximal part of esophagus greater than 60 mmHg in 46% of the patients, which was significant higher in comparison to the SLE (11.8%) and SSc-Group (0%, P = 0.003). Furthermore, IBS patients showed lower mean resting pressure of the distal esophagus sphincter (Lower esophageal sphincter, 22 mmHg) when compared with SLE (28 mmHg, P = 0.037) and SSc (26 mmHg, P = 0.052). 23.5% of patients with SLE showed amplitudes greater as 160 mmHg in the distal esophagus (IBS and SSc: 0%) whereas 29.4% amplitudes greater as 100 mmHg in the middle one (IBS: 16.7%, SSc: 5.9% respectively, P = 0.006). Patients with SSc demonstrated, as expected, in almost half of the cases reduced peristalsis or even aperistalsis in the lower two thirds of the esophagus. SSc patients demonstrated a negative correlation coefficient between dysphagia score, amplitude and velocity of peristaltic activity at middle and lower esophagus [r = -0.6, P < 0.05].

CONCLUSION: IBS patients have comparable dysphagia-scores as patients with autoimmune disorders. The different manometric patterns might allow differentiating esophageal symptoms based on IBS from other organic diseases.

Core tip: This is the first comparative study concerning esophageal motility among functional and autoimmune disorders. Patients in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-group showed comparable dysphagia-scores as patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. Nevertheless, different manometric patterns between the three examined groups were observed, which might allow differentiating esophageal symptoms based on IBS from other organic diseases.

- Citation: Thomaidis T, Goetz M, Gregor SP, Hoffman A, Kouroumalis E, Moehler M, Galle PR, Schwarting A, Kiesslich R. Irritable bowel syndrome and organic diseases: A comparative analysis of esophageal motility. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(38): 6408-6415

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i38/6408.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6408

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterized mainly by symptoms as diarrhoea, constipation and diffuse abdominal pain[1]. The prevalence of IBS in the western population varies between 15% and 20%[2-7] with an overall 2:1 female predominance[5]. In 2006 the Rome III criteria for diagnosis and classification of IBS were established[8]. According to these criteria IBS is defined as recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort associated with altered defecation.

Dyspepsia and dysphagia are commonly reported of IBS patients. However, there are no comparative data available dealing with esophagus motility in IBS patients compared to autoimmune disorders. Analyses of peristaltic changes of the esophagus in patients with IBS have led to controversial findings[9-13]. Reduced resting pressure and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES)[9,11], abnormal contractions up to 150 mmHg[10] as well as normal peristaltic motility in patients with IBS[12] have been described.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) show a variety of visceral manifestations. Skin, joints, lungs, nervous system and internal organs can be affected. Dysfunction of esophagus motility is reported in about 70%-90% of patients with SSc[14-18]. In patients with SLE the percentage varies between 1.5% and 25%[19]. Aim of the present study was to assess the esophageal motility function in patients with IBS compared to organic diseases (SLE and SSc).

Patients were prospectively invited to participate at this single centre study. Patients were identified based on the database of our outpatient clinic of gastroenterology and rheumatology at the University Mainz. Patients with IBS, SLE and SSc were able to participate. The database showed 115 patients with one of the mentioned diseases. 74 patients were screened and 56 patients agreed to participate in the study and were included (15 patients with IBS, 22 with SLE and 19 with SSc).

All SLE and SSc patients met the criteria established by the American Rheumatism Association for autoimmune diseases, whereas the patients in IBS group were included on the basis of Rome III process[8,20,21]. Patients with uncertain diagnosis, with known other severe diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract and pregnant and lactating women were excluded from the study. All patients gave their written consent. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Rheinland-Pfalz (No. 837.432.09).

Besides thorough history and physical examination, the following diagnostic methods were performed:

Blood biochemistry analysis: A complete blood biochemistry examination including blood count and biochemical analysis were performed in each patient. Furthermore, the following parameters were examined: Complement factors C3 and C4, ANA, ENA, dsDNA, CRP and ESR.

Upper endoscopy: All patients underwent esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) before entering the study. Only patients with normal endoscopic findings were included in the current study.

Esophageal manometry: Esophageal manometry was performed after 8 h of fasting. All medications which potentially could affect the esophageal motility were paused 48 h before manometry.

The measurements were performed using a 60 cm long, 8 channel lumen catheter (Sierra Scientific Instruments, Germany) with 5 distal openings separated 1 cm vertically and 3 proximal openings distributed at 5 cm distance apart.

Each of the catheter lumens was perfused with distilled water at a rate of 1.36 mL/min. The catheter was connected to an infusion system (Mui Scientific, Canada) with attached pressure converters. The catheter was initially inserted transnasally into the patient’s stomach. The patients remained in a sitting position during insertion of the catheter.

After the lumen reached the stomach, patients were brought to a horizontal position and then the pressure of the LES was measured by using the station and rapid pull-through technique[22,23].

Subsequently, the catheter was slowly withdrawn at 1 cm intervals with wet (10 mL water) and dry swallows at each level, so that a complete analysis of esophagus motility could be obtained. Ineffective swallows were not included in detailed measurements of manometric parameters.

The resulting esophageal parameters were: position, length, resting pressure and relaxation of the LES und upper esophageal sphincter (UES), mean peristaltic pressure, simultan or retrograde contractions, duration and velocity of the peristaltic waves at the proximal, medial and distal third of esophagus.

Patients were asked to complete the following questionnaires:

SLEDAI: The disease activity in patients of SLE was assessed via the SLEDAI-Index[24].

Rodnan score: The disease activity in patients with SSc was assessed via the modified Rodnan score[25].

Dysphagia score: The intensity and frequency of the esophageal symptoms was assessed as an accumulation score as described before[26]. Specifically all patients were evaluated for symptoms such as odynophagia, difficulty in swallowing, chest pain, dysphagia etc in relation to frequency, need for treatment and weight loss.

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS program (version 19.0). Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test to compare group means. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference. Sample size estimation: Distinct sample size estimation could not be performed because of lack of comparative data. However, we hypothesised that IBS patients have at least 30% different manometric outcome parameters compared to patients with autoimmune disorders, which lead to a sample size of 15 patients per group (Power 80%).

There was no statistical difference in the standard lab values in all three groups. Patients with SLE and SSc showed as expected higher incidence in expression of autoimmune antibodies such as ANA, ENA, dsDNA or altered complement concentrations.

Patients with IBS showed higher prevalence of diarrhoea compared to constipation or to the combination of diarrhoea and constipation (Table 1). Patients with SLE and SSc reported a great variety of symptoms including weakness, difficulty in swallowing or non-specific musculoskeletal tenderness that can be explained due to secondary fibromyalgia. Gender and age showed no statistical significant changes within the three groups (Table 1).

| IBS | SLE | SSc | |||

| Diarrhoea | Constipation | Diarrhoea + Constipation | |||

| Total | 8 (53.3) | 4 (26.7) | |||

| Male | 3 (100) | 0 | 0 | 2 (9.01) | 3 (15.8) |

| Female | 8 (66.7) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (25) | 20 (90.9) | 16 (84.2) |

| Age (yr) | 42 ± 16 | 56 ± 15 | 34 ± 18 | 48 ± 10 | 55 ± 9 |

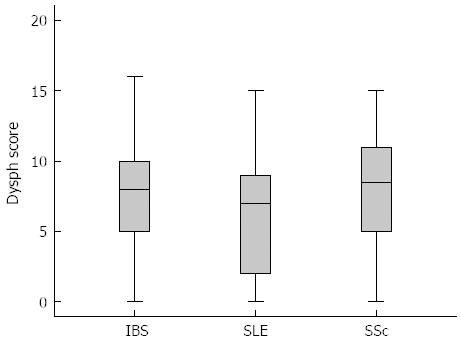

The disease activity of SLE and SSc are shown in Table 2. SSc patients tend to have a milder disease activity compared to SLE patients. However, dysphagia score was similar in all three groups without any statistical difference. The mean value of dysphagia score was in IBS group 7.3, in SLE group 6.73 and in SSc group 7.56 with a P-value > 0.05 (Figure 1).

| Modified Rodnan score | SLEDAI | |||||

| (average score) | (average score) | |||||

| Activity | No activity | 0 | 7 (39) | No activity | 0 | 4 (19) |

| Mild | 7.2 | 10 (55) | Mild | 3 | 10 (48) | |

| Moderate | 18 | 1 (6) | Moderate | 7.4 | 5 (24) | |

| Severe | - | - | Severe | 11 | 2 (9) | |

| Total | 5.2 | 18 (100) | Total | 4.2 | 21 (100) | |

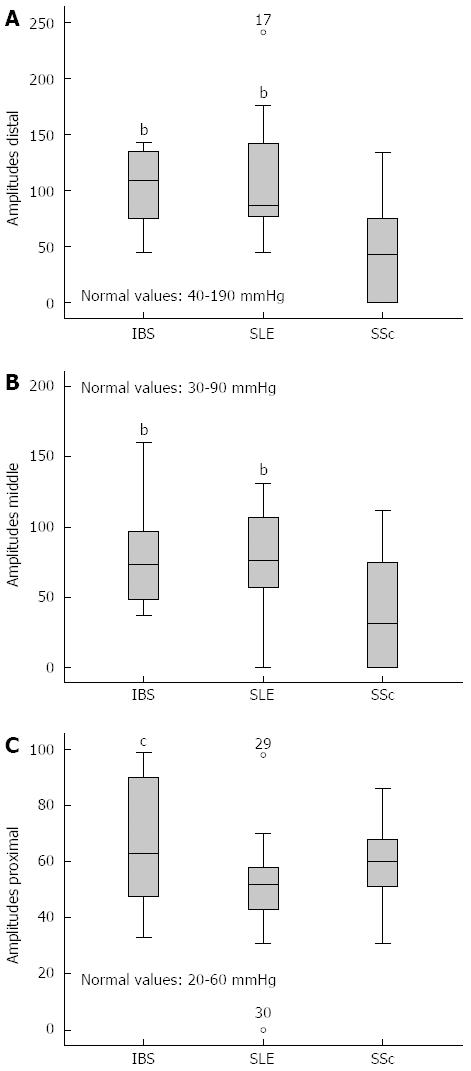

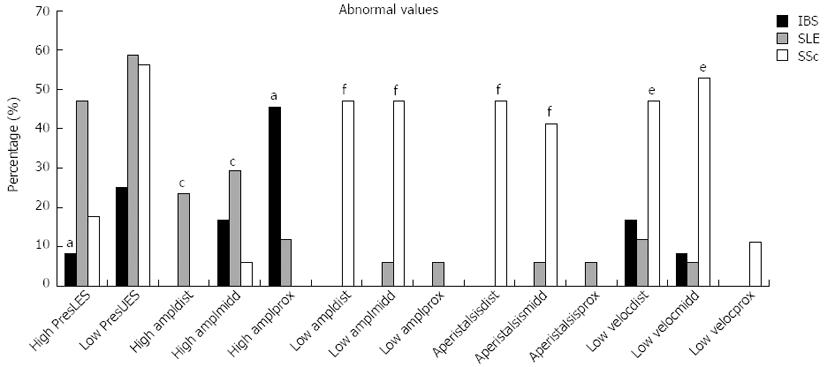

In the manometric studies we observed significant differences concerning the quality of the peristaltic waves (amplitude, duration and velocity) among the three groups (Figure 2). IBS patients showed increased peristalsis in the lower two thirds of esophagus in comparison to patients with SSc who in almost 50% of the cases manifested wide peristalsis with reduced amplitude and velocity (Figure 3). There was no significant difference between the amplitude, duration and velocity of the peristaltic movements in the lower two thirds of esophagus among patients with IBS and patients with SLE. Nevertheless 23.5% of patients with SLE showed distal amplitudes greater as 160 mmHg and 29.4% middle amplitudes greater as 100 mmHg. At the proximal esophageal part patients with IBS showed significant higher peristaltic waves also when compared with patients in the SLE group (Table 3, Figure 2). Particularly, 45.5% of IBS patients showed amplitudes greater as 60 mmHg whereas in the SLE and SSc group the rates were 11.8% and 0% respectively (Figure 3). Measurements concerning the LES showed that patients with IBS had significant lower resting pressure in comparison to patients with autoimmune disorders (Table 3). Though, no significant difference could be observed when other manometric measures between the 3 groups were examined, such as length and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter as well as duration of distal and middle peristalsis. Regarding the UES we found a significant higher resting pressure and length by patients in IBS group in comparison to SLE and SSc (Table 3). Interestingly, 58.8% of patients with SLE and 56.35% of patients with SSc showed resting pressure less than 40 mmHg (Figure 3).

| IBS | SLE | SSc | P value | |

| Lower esophageal sphincter | ||||

| Pressure (mmHg) | 22 ± 5 | 28 ± 8.9 | 26 ± 5.2 | P < 0.0512 |

| Length (cm) | 3.6 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 1 | |

| Relaxation (%) | 84.8 ± 15.4 | 89.5 ± 13.2 | 83.4 ± 10.4 | |

| Distal esophagus | ||||

| Amplitude (mmHg) | 103.6 ± 33.7 | 107.3 ± 53.3 | 43.3 ± 48.2 | P < 0.00123 |

| Duration (s) | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 1.4 | 2.9 ± 2.9 | |

| Velocity (cm/s) | 3 ± 1.6 | 2.6 ± 1 | 1.4 ± 2 | P < 0.0523 |

| Middle esophagus | ||||

| Amplitude (mmHg) | 78.3 ± 35.7 | 75.9 ± 35 | 39.2 ± 42.4 | P < 0.0123 |

| Duration (s) | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 2.2 | |

| Velocity (cm/s) | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 3.9 ± 3.4 | 1.3 ± 3.7 | P < 0.0523 |

| Proximal esophagus | ||||

| Amplitude (mmHg) | 67.3 ± 23.3 | 50.6 ± 19.8 | 58.3 ± 15.9 | P = 0.051 |

| Duration (s) | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | |

| Velocity (cm/s) | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 2.3 | 3.0 ± 2.4 | |

| Upper esophageal sphincter | ||||

| Pressure (mmHg) | 70.5 ± 22.3 | 52.7 ± 20 | 50.2 ± 17.8 | P < 0.0512 |

| Length (cm) | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | P < 0.0512 |

| Relaxation (%) | 94.7 ± 8.0 | 85.2 ± 12.7 | 87.1 ± 12 |

Correlation coefficient tests revealed a negative relation between dysphagia score, amplitude and velocity of peristaltic activity at middle and lower esophagus in SSc patients (r = -0,6, P < 0.05). A connection between dysphagia and peristaltic abnormality in IBS and SLE groups was not observed. Furthermore, there was no association between the three subgroups of IBS, the score of dysphagia and manometric findings, as well as between the presence auf autoantibodies and dysphagia among patients with SLE and SSc (data not shown).

We conducted a comparative analysis of the peristalsis of the esophagus between patients with IBS and patients with SLE and SSc. The groups consisted in 66.7% IBS, 91% SLE and 84.2% SSc of female patients mainly between 40 and 60 years, which is completely in accordance with the epidemiology of the examined diseases[27-29].

We found significant different manometric patterns in IBS patients compared to those with autoimmune disorders. It was interesting to notice that patients in the IBS group, as seen in the derived dysphagia scores, showed the same intensity and frequency of swallowing problematic as subjects in the two other categories. Specifically, patients with IBS complained about difficulties in swallowing, retrosternal sore and heartburn as frequent as patients with SLE and SSc (Figure 1). It was speculated that esophageal symptoms are mainly caused due to esophageal reflux[30,31]. However, in our study only patients with normal EGD were included and retrosternal burning was treated with PPI prior entering our study.

The most significant finding in our manometric study was that IBS patients showed very high peristaltic amplitudes in the proximal esophageal part and reduced resting pressure of the lower esophagus sphincter (Figure 3) which was statistically significant different to SSc and SLE patients.

The analysis of esophageal peristaltic activity in patients with IBS showed controversial results. Diffuse peristaltic dysfunction with amplitudes > 150 mmHg and duration > 7 s[10,32], simultan peristaltic[11] or also normal findings[12,33,34] have been reported. Reduced resting pressure of LES has already been confirmed by others studies[9,11,30]. A pathophysiologic explanation or underlying pathomechanism is not known to date, however a correlation between small bowel or colonic dysfunction has been suggested[33,35].

Our study clearly shows that IBS patients have pathologic motility patterns which are comparable to organic disorders (like SLE or SSc). However, the distribution of changes is different in IBS patients compared to SLE and SSc. A hypermotility of the proximal esophagous > 60 mmHg was seen in almost 50% of the patients. Our data suggest that altered esophageal motility is a common feature in IBS. Taken into consideration the small invasiveness of this method, esophageal manometry may have a place in the diagnostic work up of patients with suspected IBS, especially in the presence of dysphagic symptoms.

SLE patients showed significantly higher incidence of pathological manometric measurements concerning the resting pressure of LES (> 30 mmHg), the amplitudes of distal and middle peristalsis (> 160 mmHg and > 100 mmHg respectively) and the resting pressure of UES (< 40 mmHg) in comparison to IBS group. These findings, with exception to the resting pressure of the UES, are in contrast with the manometric findings in SSc, where most of the patients showed reduced peristaltic activity in the lower two thirds of esophagus (Figures 2 and 3).

Hyperperistalsis has been described from Peppercorn et al[36] reporting cases of SLE with manometric features similar to diffuse esophageal spasm. In our study, we noticed peristaltic motility similar to nutcracker esophagus with bipeaked waves and amplitudes up to 241 mmHg. Hypoperistalsis or aperistalsis, as previously described[37,38], even in a small percentage, were not observed. These findings are consistent with Gutierrez et al[38]. They described that such abnormalities are more often in SSc and mixed connective tissue diseases than in SLE.

In conclusion, this is - to the best of our knowledge - the first comparative study concerning esophageal motility among functional and autoimmune disorders. Although IBS, SLE and SSc patients showed different motility patterns, the intensity and frequency of dysphagia were comparable.

The esophageal peristalsis in patients with IBS appears to be more affected in the proximal part, where as in the autoimmune disorders in the middle and distal one. Thus, smooth muscle changes might be associated with autoimmune diseases whereas striated muscles might be more affected in patients with IBS as suggested previously[39,40]. However, the absence of direct correlation between dysphagia score and manometric parameters in patients with IBS implies that, apart from motor dysfunction, visceral hypersensitivity plays an additional role to the pathology in IBS. In deed, visceral hypersensitivity in IBS patients has been documented in older and recent studies[34,41-45] pointing various lines of evidence for its relevance in the pathophysiology of IBS. Future studies are needed to further verify our data and to evaluate whether different motility patterns can be used to diagnose IBS related motility changes of the esophagus.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract with a still unclear pathophysiology. Although patients with IBS complain predominantly about manifestations concerning the lower gastrointestinal tract, esophageal symptoms are not uncommon.

Esophageal dysmotility is frequent in patients with autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and systemic sclerosis (SSc). However, there is no comparative data available concerning esophageal motility between IBS patients and those with autoimmune disorders.

This is the first comparative study concerning esophageal motility among functional and autoimmune disorders. Patients with IBS appear to have similar grade of dysphagia in comparison to patients with autoimmune disorders such as SLE and SSc. This study shows that IBS patients have pathologic esophageal motility patterns which are comparable to organic disorders.

Esophageal manometry might have a place in the diagnostic work up of patients with suspected IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome: Functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterized mainly by symptoms as diarrhoea, constipation and diffuse abdominal pain. Systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis are autoimmune diseases with esophageal and multiple other visceral manifestations.

The authors compared the esophageal motility between patients with IBS and patients with autoimmune disorders, such as SLE and SSc, at a single university prospective study. The outcome was calculating correlation coefficient between amplitudes, velocity and duration of the peristaltic waves throughout esophagus and patients’ dysphagia for all three groups. It revealed that IBS patients showed similar pathologic dysphagia scores but were characterized from different motility patterns when compared to patients with autoimmune diseases. The results are interesting and suggest that esophageal manometry may have a place in the diagnostic work up of patients with suspected IBS, especially in the presence of dysphagic symptoms.

P- Reviewer Hu TH S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Morris AF. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2:653-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 966] [Cited by in RCA: 962] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G. Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:671-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 449] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Functional bowel disorders in apparently healthy people. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:283-288. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736-1741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM. An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 1:S1-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE, Janssens J, Funch-Jensen P, Corazziari E. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1502] [Cited by in RCA: 1426] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3381] [Article Influence: 177.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Bilić A, Jurcić D, Schwarz D, Marić N, Vcev A, Marusić M, Gabrić M, Spoljarić L. Impaired esophageal function in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Coll Antropol. 2008;32:747-753. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lanng C, Mortensen D, Friis M, Wallin L, Kay L, Boesby S, Jørgensen T. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in a community sample of subjects with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Digestion. 2003;67:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Whorwell PJ, Clouter C, Smith CL. Oesophageal motility in the irritable bowel syndrome. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981;282:1101-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Soffer EE, Scalabrini P, Pope CE, Wingate DL. Effect of stress on oesophageal motor function in normal subjects and in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1988;29:1591-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Alekseenko SA, Krapivnaia OV, Kamalova OK, Vasiaev VIu, Pyrkh AV. [Dynamics of clinical symptoms, indices of quality of life, and the state of motor function of the esophagus and rectum in patients with functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome after Helicobacter pylori eradication]. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2003;54-58, 115. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Akesson A, Wollheim FA. Organ manifestations in 100 patients with progressive systemic sclerosis: a comparison between the CREST syndrome and diffuse scleroderma. Br J Rheumatol. 1989;28:281-286. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sjogren RW. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1265-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Folwaczny C, Voderholzer W, Riepl RL, Schindlbeck N. [Clinical aspects, pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal manifestations of progressive systemic scleroderma]. Z Gastroenterol. 1996;34:497-508. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ebert EC. Esophageal disease in scleroderma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:769-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bassotti G, Battaglia E, Debernardi V, Germani U, Quiriconi F, Dughera L, Buonafede G, Puiatti P, Morelli A, Spinozzi F. Esophageal dysfunction in scleroderma: relationship with disease subsets. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2252-2259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hoffman BI, Katz WA. The gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1980;9:237-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3641] [Cited by in RCA: 3788] [Article Influence: 84.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, Schaller JG, Talal N, Winchester RJ. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9555] [Cited by in RCA: 10029] [Article Influence: 233.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hay DJ, Goodall RJ, Temple JG. The reproducibility of the station pullthrough technique for measuring lower oesophageal sphincter pressure. Br J Surg. 1979;66:93-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ, Stef JJ, Miller WN, Lydon SB, Arndorfer RC. A rapid pull-through technique for measuring lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:437-443. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3258] [Cited by in RCA: 3513] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Brennan P, Silman A, Black C, Bernstein R, Coppock J, Maddison P, Sheeran T, Stevens C, Wollheim F. Reliability of skin involvement measures in scleroderma. The UK Scleroderma Study Group. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pope CE. The quality of life following antireflux surgery. World J Surg. 1992;16:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mayes MD. Scleroderma epidemiology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29:239-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wilson S, Roberts L, Roalfe A, Bridge P, Singh S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:495-502. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Smart HL, Nicholson DA, Atkinson M. Gastro-oesophageal reflux in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1986;27:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee SY, Lee KJ, Kim SJ, Cho SW. Prevalence and risk factors for overlaps between gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia, and irritable bowel syndrome: a population-based study. Digestion. 2009;79:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Uścinowicz M, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Kaczmarski M. [Motility disorders in oesophageal manometry in children with chronic abdominal pain]. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2004;16:34-36. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Lind CD. Motility disorders in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:279-295. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Costantini M, Sturniolo GC, Zaninotto G, D’Incà R, Polo R, Naccarato R, Ancona E. Altered esophageal pain threshold in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:206-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Katiraei P, Bultron G. Need for a comprehensive medical approach to the neuro-immuno-gastroenterology of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2791-2800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Peppercorn MA, Docken WP, Rosenberg S. Esophageal motor dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Two cases with unusual features. JAMA. 1979;242:1895-1896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Castrucci G, Alimandi L, Fichera A, Altomonte L, Zoli A. [Changes in esophageal motility in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: an esophago-manometric study]. Minerva Dietol Gastroenterol. 1990;36:3-7. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Gutierrez F, Valenzuela JE, Ehresmann GR, Quismorio FP, Kitridou RC. Esophageal dysfunction in patients with mixed connective tissue diseases and systemic lupus erythematosus. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | White AM, Upton ARM, SM C. Generalised smooth muscle hyperresponsiveness in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Invest Med. 1988;11:C42. |

| 40. | Smart HL, Atkinson M. Abnormal vagal function in irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1987;2:475-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhou Q, Zhang B, Verne GN. Intestinal membrane permeability and hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2009;146:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ludidi S, Conchillo JM, Keszthelyi D, Van Avesaat M, Kruimel JW, Jonkers DM, Masclee AA. Rectal hypersensitivity as hallmark for irritable bowel syndrome: defining the optimal cutoff. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:729-33, e345-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | van der Veek PP, Van Rood YR, Masclee AA. Symptom severity but not psychopathology predicts visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, Tack J, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1113-1123. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Ritchie J. Pain from distension of the pelvic colon by inflating a balloon in the irritable colon syndrome. Gut. 1973;14:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |