Published online Oct 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6193

Revised: July 14, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: October 7, 2013

Processing time: 127 Days and 10.8 Hours

AIM: To determine whether an increased number and duration of non-acid reflux events as measured using the multichannel intraluminal impedance pH (MII-pH) is linked to gastroparesis (GP).

METHODS: A case control study was conducted in which 42 patients undergoing clinical evaluation for continued symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (both typical and atypical symptoms) despite acid suppression therapy. MII-pH technology was used over 24 h to detect reflux episodes and record patients’ symptoms. Parameters evaluated in patients with documented GP and controls without GP by scintigraphy included total, upright, and supine number of acid and non-acid reflux episodes (pH < 4 and pH > 4, respectively), the duration of acid and non-acid reflux in a 24-h period, and the number of reflux episodes lasting longer than 5 min.

RESULTS: No statistical difference was seen between the patients with GP and controls with respect to the total number or duration of acid reflux events, total number and duration of non-acid reflux events or the duration of longest reflux episodes. The number of non-acid reflux episodes with a pH > 7 was higher in subjects with GP than in controls. In addition, acid reflux episodes were more prolonged (lasting longer than 5 min) in the GP patients than in controls; however, these values did not reach statistical significance. Thirty-five patients had recorded symptoms during the 24 h study and of the 35 subjects, only 9% (n = 3) had a positive symptom association probability (SAP) for acid/non-acid reflux and 91% had a negative SAP.

CONCLUSION: The evaluation of patients with a documented history of GP did not show an association between GP and more frequent episodes of non-acid reflux based on MII-pH testing.

Core tip: Gastroparesis (GP) has been thought to occur in about 8%-10% of patients who suffer from refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). There have been no formal studies to date that have evaluated whether patients with refractory GERD additionally suffer from GP. Our study aimed to investigate whether patients who experience continued symptoms of GERD despite acid suppression therapy also concurrently have gastroparesis. By using multichannel intraluminal impedance pH technology, we were not able to find an association between patients with refractory GERD and gastroparesis.

- Citation: Tavakkoli A, Sayed BA, Talley NJ, Moshiree B. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients refractory to proton pump inhibitor therapy: Is gastroparesis a factor? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(37): 6193-6198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i37/6193.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i37.6193

Gastroparesis (GP) is a chronic gastrointestinal (GI) motility disorder characterized by delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical outlet obstruction[1]. The most common etiologies of GP include those secondary to chronic disease states such as diabetes mellitus and collagen-vascular diseases, post-surgical causes, medication induced, and idiopathic causes[1,2]. Symptoms of GP include early satiety, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, and gastroesophageal reflux[1-3]. Notably, GP has been rising in prevalence across the United States, which as a result, has led to an increase in GP related hospitalizations and increasing health care costs[1,4].

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a very common disease in the United States and has recently been show to be the most common GI diagnosis among clinical visits in the United States[5]. The mainstay of treatment for GERD includes proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) but several studies have shown that upwards of 40% of patients who suffer from heartburn have either a partial or complete lack of response to PPIs taken once a day[6-8]. A number of causes for PPI failure have been investigated, including medication non-compliance, undiagnosed functional bowel disorders, and GP[9].

GP has been reported to be present in a variable subset of patients who suffer from refractory GERD and studies have shown that anywhere between 8%-10% of patients with refractory GERD additionally suffer from GP[10-14]. It is unknown whether the hypothesized link between GP and refractory GERD actually exists in clinical practice. The aim of our study was to determine whether there is an increased number and duration of non-acid reflux events when comparing patients with GP and without GP using multichannel intraluminal impedance pH (MII-pH). Given the delayed gastric emptying of food in patients with GP, we hypothesized that patients with GP will experience a greater number of non-acid reflux episodes for a longer duration of time when compared to controls without GP.

The University of Florida Health Science Center Institutional Review Board approved the collection and analysis of MII-pH data obtained in this study.

From July 2009 to September 2010, all patients who underwent MII-pH analysis for continued symptoms of GERD despite PPI therapy were enrolled after signing informed consent (n = 66). The patients’ health records were reviewed for evidence of a prior gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) done at the University of Florida (n = 39) or the results were documented in a recent clinic note from a prior GES done at an outside institution (n = 3). Patients were then included in this study if a GES was previously done (abnormal at University of Florida if t1/2 > 90 min) and they were scheduled to or had undergone a MII-pH study at the gastric motility laboratory at University of Florida. Patients were excluded from the study if they had no prior GES or history of one documented in a recent clinical note. However, patients were not excluded if they were currently on anti-acid therapy. All patients underwent a physical examination and upper endoscopy prior to undergoing the ambulatory MII-pH testing to exclude any mechanical obstruction.

Patients were considered refractory to PPI therapy at the discretion of the clinician who had referred them to receive MII-pH analysis. Patients were defined as “refractory” if they continued to have symptoms of GERD despite anti-acid therapy. All patients remained on their previously prescribed PPI therapy during the duration of the study.

Subjects presented to the motility laboratory after an overnight fast. The Sleuth ambulatory system (Sandhill Scientific, Inc; Highlands Ranch, CO, United States) was used to perform the impedance testing. The catheter has an antimony pH electrode measuring the pH 5 cm from the distal tip and 6 impedance electrodes that measures impedance at 3, 5, 7, 9, 15 and 17 cm above the distal tip. The catheter was placed transnasally with its tip 5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter.

Subjects then underwent a 24-h monitoring in which their symptoms were electronically recorded and the patients kept a diary of their food intake. All 42 subjects were continued on their current acid suppression therapy for the entire duration of the study. All prokinetic agents, including bethanechol, domperidone, metoclopramide, and azithromycin were discontinued.

Symptoms recorded in the electrical diaries included both typical GERD symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, and chest pain) and atypical GERD symptoms (cough, hoarseness, abdominal discomfort, nausea, belching, globus sensation, and dysphagia). After the 24-h ambulatory period, subjects returned to the motility laboratory where the data was transferred and analyzed using a single investigatory dedicated software (BioView Analysis; Sandhill Scientific, Inc.). Two investigators in the motility laboratory manually reviewed tracings and electronic diary entry of symptoms. Meal periods were marked and excluded from the analysis. Only liquid and mixed liquid/gas reflux episodes were evaluated for this study.

The parameters obtained from the MII-pH device included the total, upright, and supine number of acid and non-acid reflux episodes, the duration of acid and non-acid reflux in a 24-h period, and the number of reflux episodes lasting longer than 5 min. The MII-pH detected reflux episodes that were classified as acidic when the esophageal pH fell below 4, non-acidic if the pH was between 4-7, and alkaline if the pH rose above 7.

Based on the MII-pH data, we evaluated each separate symptom and determined their association with a reflux episode. The symptom association probability (SAP) was electronically calculated using the BioView Analysis Software. The 24-h pH data was divided into 2-min segments and each of the 2 min segments were studied to determine whether a reflux event and a symptom occurred during that segment. A 2 × 2 table was made in which the number of two minute segments with and without reflux and with and without symptoms were tabulated. A χ2 test was then used to determine whether the occurrence of the symptoms and reflux could have occurred by chance. The SAP was then calculated using the formula SAP = (1 - P) × 100% and it was considered positive if > 95%[15].

The impedance pH data was compared using the Wilcoxon non-parametric analysis of variance for means and the 2-sided Fisher exact test for proportions. All values are expressed as a mean ± SD. The null hypothesis assumes that no significant difference in the number of non-acid reflux events will be seen when comparing impedance pH data between the GP group and the control group.

The study included 42 participants chosen based on their GES results and then divided into two groups: subjects with gastroparesis and subjects with normal GES both undergoing MII-pH for continued symptoms of GERD despite PPI therapy.

The GP group included 16 patients with a mean age of 54 ± 14 years (age range: 24-76 years) with a mean GES half-time (t1/2) of 134 ± 59 min (normal defined at UF as t1/2 between 45-90 min). The control group consisted of 26 patients with a mean age of 51 ± 13 years (age range: 24-77 years) with a mean GES (t1/2) of 65 ± 13 min (Table 1). Among the GP group, 6 patients had a normal esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and 7 patients had biopsy proven Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) negative gastritis (Table 1). In the control group, 11 patients had a normal EGD and 6 patients had biopsy proven H. pylori negative gastritis (Table 1).

| Result | GP | Controls | P value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 54 ± 14 | 51 ± 13 | 0.620 |

| Female (n) | 12 | 19 | |

| Males (n) | 4 | 7 | |

| Gastric emptying scintigraphy | |||

| t1/2 time (mean ± SD, min) | 134 ± 59 | 65 ± 13 | 0.0003 |

| Comorbidities (n) | |||

| GERD | 16 | 26 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 2 | 1 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | 2 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | 4 | |

| Chronic constipation | 3 | 2 | |

| Hepatitis C | 1 | 1 | |

| IBD | 1 | 0 | |

| Previous surgical procedures (n) | |||

| Cholecystectomy | 4 | 6 | |

| Nissen Fundoplication | 3 | 1 | |

| EGD status (n) | |||

| Normal EGD | 6 | 11 | |

| Gastritis (H. pylori negative) | 7 | 6 | |

| Atrophic gastritis | 1 | 0 | |

| Fundic gland polyp | 2 | 0 | |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 0 | 1 | |

| Antacid usage (n) | |||

| H2 blocker therapy | 2 | 5 | |

| Daily | 1 | 3 | |

| Bid | 1 | 1 | |

| Tid | 0 | 1 | |

| PPI therapy (n) | 14 | 15 | |

| Daily | 4 | 4 | |

| Bid | 9 | 10 | |

| Tid | 1 | 1 | |

| Sucralfate (n) | 2 | 3 | |

| Antacids (n) | 1 | 1 | |

| No therapy (n) | 0 | 3 | |

Symptoms on presentation among both the GP and control group included heartburn, bloating, nausea/vomiting chest pain, and hoarseness. Concurrent medical diagnoses included GERD, irritable bowel syndrome, type II diabetes mellitus, and chronic constipation. Prior surgical procedures in both populations included cholecystectomy and Nissen fundoplication.

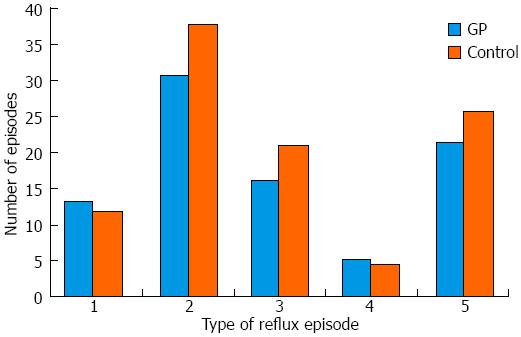

No statistical difference was seen between subjects with GP and controls with respect to the total number and duration of acid reflux events [13.3 ± 17.1 (95%CI: 4.2-22.4) in GP vs 12.0 ± 14.8 (95%CI: 6.0-18.0) in controls, P < 0.79], total number and duration of non-acid reflux events [21.6 ± 24.6 (95%CI: 8.5-34.7) in GP vs 25.7 ± 29.3 (95%CI: 13.9-37.5) in controls, P < 0.64], or the total number and duration of reflux events [30.8 ± 36.5 (95%CI: 11.3-50.2) in GP vs 37.9 ± 35.7 (95%CI: 23.48-52.29) in controls, P < 0.54] (Figure 1). The number of non-acid reflux episodes with a pH > 7 were higher in subjects with GP [5.3 ± 5 (95%CI: 2.6-8.0) vs 4.5 ± 5.6 (95%CI: 2.3-6.9) in controls, P < 0.67] and the acid reflux episodes were more prolonged (lasting longer than 5 min) in the GP group [0.95 ± 2.0 (95%CI: -1.1-2.0) vs 0.25 ± 0.7 (95%CI: -1.1-0.5) in controls], but these values did not reach statistical significance (P < 0.12) (Figure 1).

Of the 42 subjects who were evaluated, 35 subjects (83%) recorded symptoms during the 24-h study period and 7 patients did not have any recorded symptoms. There were 87 total symptoms recorded by the 35 subjects and 33% were typical symptoms and 67% were atypical symptoms of GERD. The GP group accounted for 38% (n = 11) of the total typical symptoms reported and the control group accounted for 62% (n = 18) of typical symptoms. Atypical symptoms of GERD were also more commonly recorded in the control group than the GP group (59% vs 41% respectively) (Table 2).

| MII-pH symptoms | Gastroparesis (n) | Controls (n) | Positive SAP (n) | Negative SAP (n) |

| Chest pain | 3 | 5 | 1 | 7 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| Regurgitation | 3 | 4 | 0 | 14 |

| Hoarseness | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Heartburn | 5 | 9 | 0 | 4 |

| Globus sensation | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Dysphagia | 4 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| Cough | 3 | 7 | 1 | 9 |

| Abdominal pain | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Belching | 6 | 8 | 0 | 14 |

| Bloating | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Of the 35 subjects who had recorded symptoms during their MII-pH testing, only 9% (n = 3) had a positive SAP for acid/non-acid reflux and 91% (n = 32) had a negative SAP. Similarly, of the total typical symptoms that were recorded, 7% (n = 2) had a positive SAP and 93% (n = 27) had a negative SAP. Of the 58 atypical symptoms recorded, 3% (n = 2) had a positive SAP and 97% (n = 56) had a negative SAP. Among the 16 subjects with GP, a total of 35 symptoms were recorded and all had a negative SAP. Among the 26 controls, 52 symptoms were recorded, and 8% of those had a positive SAP with the majority (92%) having a negative SAP.

Resistance to acid suppression therapy such as PPIs is the most common presentation of GERD in the tertiary care GI practices[16]. A survey of GERD patients receiving PPI therapy shows that 25%-42% of patients are refractory to a once-daily PPI dose, of which only 25% would respond to an increase in PPI dosing to twice daily[17,18]. In addition, 42% of GERD patients surveyed are dissatisfied with their PPI treatment outcomes[19]. GP has long been thought of as a risk factor for refractory GERD due to the impaired gastric accommodation, delayed gastric emptying and the subsequent loss of lower esophageal sphincter tone. Furthermore, as our study shows, symptoms of GP and GERD often overlap as both patients can complain of epigastric pain, abdominal bloating, nausea, and vomiting making it difficult to distinguish between the two disease processes. Given this observed overlap of symptoms, our study aimed to determine whether patients with GP and concurrent symptoms of reflux despite concurrent PPI therapy have an increased frequency and duration of non-acid reflux using impedance pH technology, as compared to those with normal gastric emptying.

Our results indicate that the total number and duration of acid, non-acid, and total reflux events was similar in GP and non-GP cases. While the number of alkaline events was slightly higher in the GP group, these alkaline reflux events represented a small percentage of the total non-acid reflux events observed (20%). Moreover, among the 35 patients who recorded symptoms during the 24 h MII-pH study, only 3 patients had a positive SAP for acid/non-acid reflux. Our findings do not support some prior studies indicating up to 40%-50% of patients with GERD have GP[12,20], and we believe that GP likely accounts for a small percentage of refractory GERD cases than previously evaluated based on conventional pH testing. Our findings based on MII-pH testing indicate that neither acid nor non-acid reflux occur more frequently in patients with GP than those without.

Since only 3 of 35 patients had a positive SAP for acid and non-acid reflux, and given our lack of statistical correlation between GP and acid or non-acid reflux, other causes of refractory GERD need to be explored to explain patients’ persistent symptoms. Notably, even the control group with refractory GERD symptoms had a poor symptom correlation with acid and non-acid reflux events. One possible explanation may be the presence of esophageal hypersensitivity, which has been proposed previously as an underlying mechanism in this patient population[16,18,21]. Esophageal distention occurs due to increased reflux volume exposing the esophagus to acidic/non-acid components of the refluxate, which in turn leads to persistent impairment of esophageal mucosa and thus results in esophageal hypersensitivity[21]. In our study, 67% of the reflux events recorded were non-acid with no correlation to patients’ symptoms, making esophageal hypersensitivity a plausible explanation for their continued symptoms.

Our study has some limitations. First, this study was limited to one tertiary care center and the small sample size (n = 42 total with 16 subjects with GP) compromised the overall generalizability of the study, leading to a statistical type II error. This may account for our negative findings indicating a lack of difference in acid and non-acid reflux in patients with and without GP. Based on the mean number of acid reflux events in GP and control groups (P = 0.09), the statistical power in the current study is 8%. Post hoc power analysis suggests that to achieve 90% statistical power, a sample size of 2592 for each group is necessary. In addition, the GES testing done was not based on the current national standard protocol for obtaining GES and some of the GES studies were not obtained at our institution therefore the accuracy of the measurements may influence our results[22]. This lack of uniformity of GES testing across multiple centers introduces a potential area for error, as patients with or without GP might have been misdiagnosed given lack of standardization. Furthermore, performing the MII-pH study on PPI therapy, as done in our study, may have affected our results in terms of delaying gastric emptying as shown in several studies which could lead to a type II error. By delaying acid-dependent peptic activity, PPIs impair hydrolytic digestion and therefore delay gastric emptying[23]. This finding may have clinical implications in the management of GERD in our subjects. Future studies evaluating the effect of GP on acid and non-acid reflux should be done with subjects strictly off PPI therapy 5 d prior to testing. Another limitation is that not all patients were maxed out on PPI therapy prior to the MII-pH study, making continued reflux a potential cause of their continued symptoms. Lastly, GES and MII-pH studies were completed on separate days and in most cases months apart and as a considerable intra-individual variability exists with gastric motility, this may also have contributed to achieving the negative results seen in this study[22].

Our study has several important strengths. This is the first study evaluating whether an association exists between GP and non-acid reflux analyzed by MII-pH monitoring. While GP may have been thought to be associated with refractory GERD, studies have not validated this finding using MII-pH to diagnose acid and non-acid reflux. In addition, the idea that delayed gastric emptying is associated with GERD has been the basis of using prokinetic drugs for the treatment of GERD[20]. Considering our results, it might not be necessary to start these patients on prokinetic agents in addition to acid suppression therapy, unless evidence of esophageal dysmotility is found on esophageal manometry testing, given these drugs have significant side effects and drug-drug interactions. Other medications that improve LES pressure or decrease transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter may be more beneficial for patients with any type of reflux, acid or nonacid, than perhaps improving their gastric emptying. Moreover, our study illustrates that patients with weakly acidic and alkaline reflux likely suffer from esophageal hypersensitivity rather than continued reflux or GP as the main cause of their typical and atypical GERD symptoms. Finally, our study justifies a larger study in which a population of patients with refractory GERD off PPI therapy is evaluated for GP in close proximity to their initial MII-pH analysis combined with manometric esophageal testing. A larger study using the MII-pH as the gold standard for diagnosing non-acid reflux would better delineate whether GP and non-acid reflux are clearly associated.

In conclusion, whether gastroparesis contributes to refractory reflux remains to be established. However, based on our pilot study, a clear relationship does not exist but further studies using larger populations of patients undergoing impedance testing for refractory reflux would help to delineate this relationship.

Up to 40% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) have either a partial or incomplete response to proton-pump inhibitors. Gastroparesis has been hypothesized to be a potential cause of refractory GERD in a subset of patients.

In a case-control study, 42 patients undergoing clinical evaluation for continued heartburn and regurgitation despite acid suppression therapy were evaluated with multi-channel intraluminal impedance pH monitoring and for evidence of gastroparesis.

Their results did not show a difference between acid and non-acid reflux events among patients with gastroparesis and those without the disease process.

While a clear relationship between gastroparesis and refractory GERD was not shown in their study, the results could be used to conduct further studies using larger populations of patients to help further delineate the relationship.

Multi-channel intraluminal impedance pH monitoring is a new technology that can detect intraluminal bolus movement without radiation. When it is combined with pH testing, it can detect both acid and non-acid reflux.

The current study is a relevant paper dealing with a difficult to treat and often poorly assessed patient population.

P- Reviewers Chiarioni G, Savarino E, Tosetti C, Van Rensburg C S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-37; quiz 38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Camilleri M, Grover M, Farrugia G. What are the important subsets of gastroparesis? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:597-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hyett B, Martinez FJ, Gill BM, Mehra S, Lembo A, Kelly CP, Leffler DA. Delayed radionucleotide gastric emptying studies predict morbidity in diabetics with symptoms of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:445-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang YR, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis-related hospitalizations in the United States: trends, characteristics, and outcomes, 1995-2004. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:313-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in RCA: 1466] [Article Influence: 112.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Hershcovici T, Fass R. An algorithm for diagnosis and treatment of refractory GERD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:923-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fass R. Proton pump inhibitor failure--what are the therapeutic options? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 2:S33-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hershcovici T, Fass R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease that does not respond well to proton pump inhibitors. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:367-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fass R. Therapeutic options for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27 Suppl 3:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galindo G, Vassalle J, Marcus SN, Triadafilopoulos G. Multimodality evaluation of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms who have failed empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:443-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Keshavarzian A, Bushnell DL, Sontag S, Yegelwel EJ, Smid K. Gastric emptying in patients with severe reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:738-742. [PubMed] |

| 12. | McCallum RW, Berkowitz DM, Lerner E. Gastric emptying in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:285-291. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Stacher G, Lenglinger J, Bergmann H, Schneider C, Hoffmann M, Wölfl G, Stacher-Janotta G. Gastric emptying: a contributory factor in gastro-oesophageal reflux activity? Gut. 2000;47:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Richter JE. How to manage refractory GERD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:658-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Weusten BL, Roelofs JM, Akkermans LM, Van Berge-Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. The symptom-association probability: an improved method for symptom analysis of 24-hour esophageal pH data. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1741-1745. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Tsoukali E, Sifrim D. The role of weakly acidic reflux in proton pump inhibitor failure, has dust settled? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:258-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bardhan KD. The role of proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9 Suppl 1:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)--acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Revicki DA, Crawley JA, Zodet MW, Levine DS, Joelsson BO. Complete resolution of heartburn symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1621-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cunningham KM, Horowitz M, Riddell PS, Maddern GJ, Myers JC, Holloway RH, Wishart JM, Jamieson GG. Relations among autonomic nerve dysfunction, oesophageal motility, and gastric emptying in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1991;32:1436-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Emerenziani S, Sifrim D, Habib FI, Ribolsi M, Guarino MP, Rizzi M, Caviglia R, Petitti T, Cicala M. Presence of gas in the refluxate enhances reflux perception in non-erosive patients with physiological acid exposure of the oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57:443-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tougas G, Chen Y, Coates G, Paterson W, Dallaire C, Paré P, Boivin M, Watier A, Daniels S, Diamant N. Standardization of a simplified scintigraphic methodology for the assessment of gastric emptying in a multicenter setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rasmussen L, Oster-Jørgensen E, Qvist N, Pedersen SA. The effects of omeprazole on intragastric pH, intestinal motility, and gastric emptying rate. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |