Published online Sep 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5877

Revised: May 24, 2013

Accepted: June 5, 2013

Published online: September 21, 2013

Processing time: 252 Days and 18 Hours

AIM: To find a non-invasive strategy for detecting choledocholithiasis before cholecystectomy, with an acceptable negative rate of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

METHODS: All patients with symptomatic gallstones were included in the study. Patients with abnormal liver functions and common bile duct abnormalities on ultrasound were referred for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Patients with normal ultrasound were referred to magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. All those who had a negative magnetic resonance or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography.

RESULTS: Seventy-eight point five percent of patients had laparoscopic cholecystectomy directly with no further investigations. Twenty-one point five percent had abnormal liver function tests, of which 52.8% had normal ultrasound results. This strategy avoided unnecessary magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in 47.2% of patients with abnormal liver function tests with a negative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography rate of 10%. It also avoided un-necessary endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in 35.2% of patients with abnormal liver function.

CONCLUSION: This strategy reduces the cost of the routine use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, in the diagnosis and treatment of common bile duct stones before laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Core tip: This strategy reduces the cost of the routine use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, in the diagnosis and treatment of common bile duct stones before laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

- Citation: Al-Jiffry BO, Elfateh A, Chundrigar T, Othman B, AlMalki O, Rayza F, Niyaz H, Elmakhzangy H, Hatem M. Non-invasive assessment of choledocholithiasis in patients with gallstones and abnormal liver function. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(35): 5877-5882

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i35/5877.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5877

Gallstone disease is one of the most common surgical problems worldwide. Both environmental and genetic factors are known to contribute to susceptibility to the disease[1]. It has been reported that in Saudi Arabia there is an increasing incidence of gallstone disease[2], especially in the high altitude provinces in the Asir[3] and Taif regions[4], and similar findings have been reported for other countries that have similar environmental and nutritional factors[5,6]. Complications of gallstone disease vary from simple recurrent biliary colic to life-threatening conditions such as ascending cholangitis and pancreatitis. In addition, the disease is thought to be a risk factor for developing pancreaticobiliary cancer, particularly in patients with choledocholithiasis [common bile duct stones (CBDS)], approximately 10% of patients with symptomatic gallstones[7].

Since symptomatic gallstone is a common indication for surgery, an accurate preoperative detection of CBDS is imperative in order to decrease operative risks and health care costs[7-9]. Better detection and treatment of CBDS before laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) would help deliver an appropriate, fast, and cost effective treatment[10]. Liver function tests (LFTs) and abdominal ultrasonography (USG), combined with medical history and clinical examinations are currently the standard preoperative methods used to diagnose patients with gallstones[9-14]. However, this approach is often not accurate enough to establish a firm diagnosis of CBDS[4,8,9].

Imaging tests are routinely used to confirm a choledocholithiasis diagnosis. While abdominal USG is the most commonly used screening modality, other imaging tests used for this purpose include endoscopic and laparoscopic USG, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

ERCP was the gold standard for diagnosing and treating CBDS; however, it is invasive, has associated morbidity and mortality, and has been shown to have a negative rate up to 75% in some studies[5]. Therefore, it was abandoned as a diagnosing method and used only for stone extraction.

MRCP is a noninvasive procedure with no associated morbidity that has become the gold standard in diagnosing CBDS; however, it should only be used when proper indications are observed[9-14] due to its high cost and limited availability[11,15,16]. Many authors have proposed its routine use[17-19] in all patients with suspected CBDS, however, in high probability patients, its cost and the need for ERCP to remove the stones makes it questionable.

IOC is particularly valuable in patients with unclear anatomy and those with preoperative predictors of choledocholithiasis but negative findings on MRCP[20,21]. Many scoring indices and guidelines have been developed to determine acceptable preoperative indications for IOC, but none so far have proved satisfactory[9,22-24]. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to find a non-invasive preoperative approach, using MRCP, ERCP, and IOC, to diagnose and treat CBDS prior to performing LC.

We conducted a prospective study on all patients with symptomatic gallstones who presented at Al Hada Armed Forces Hospital in Taif, Saudi Arabia from April 2006 to April 2010. Patients not fit for surgery were excluded from the study. In addition, patients who presented with acute pancreatitis were excluded since we have a different protocol for them in our center. The study was approved by the local committee on human research, and all patients gave written informed consent. All patients underwent detailed preoperative evaluations consisting of clinical history, laboratory testing including LFT, (serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase), and USG examination.

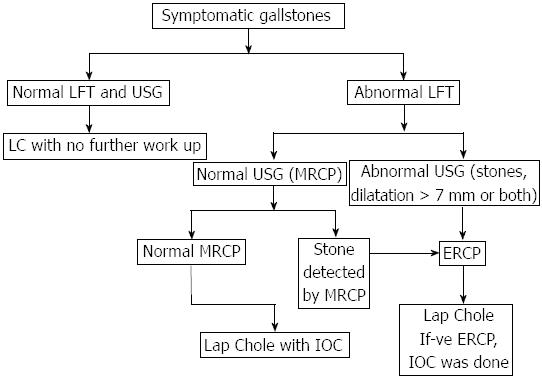

An algorithm was designed (Figure 1). Patients with normal LFT and no bile duct abnormalities were referred for LC without further work-up. Patients with abnormal LFT and USG proven CBDS and/or bile duct dilatation > 7 mm were referred for ERCP for stone removal, followed by LC. Patients with abnormal LFT and normal bile ducts (determined by USG) were referred for MRCP, and if CBDS were detected, they were referred for ERCP for stone removal, followed by LC. MRCP and ERCP negative cases underwent LC with IOC to detect false negative cases and avoid retained stones. For these patients, intraoperative discovery of CBDS would indicate stone removal by ERCP in the same sitting with the LC.

SPSS 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago Illinois) was used for carrying out statistical analysis. Group differences were further analyzed by χ2 and difference between means of continuous variables was tested by Student’s t test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was adopted to control for confounders and level of significance was determined at P < 0.05.

A total of 896 patients were included in the study. Table 1 shows the patient demographic information. Out of these, 703 (78.5%) patients underwent LC without any further workup. Patients who had abnormal LFTs [193 (21.5%)] were older and there were more males in this group.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Total number of patients | 896 |

| Female patients | 717 (80) |

| Male patients | 179 (20) |

| Mean age of females (yr) | 41.4 ± 21.3 |

| Mean age of males (yr) | 45.0 ± 21.6 |

| Number of patients underwent LC without MRCP or/and ERCP | 703 (78.5) |

| Number of patients with abnormal liver functions. | 193 (21.5) |

| Female patients | 116 (60) |

| Male patients | 77 (40) |

| Mean age of females (yr) | 55.6 ± 19.6 |

| Mean age of males (yr) | 60.7 ± 19.8 |

Table 2 demonstrates the breakdown of all the patients with abnormal LFT. CBD abnormalities were detected on USG in 91 (47.2%) patients and ERCP was used to extract stones in 90% of them. Abnormal LFT results, in which USG found dilatation but no stones were observed in 28 patients. The mean CBD diameter was 8.8 mm in these patients, with stones being extracted by ERCP in 85.7%. In 40 patients with abnormal LFT results and for whom USG detected both dilatation and stones, the mean CBD diameter was 9 mm, with stones being extracted by ERCP in 90%.

| Findings | Patient | Stones | Mean T.Bili | Mean Al-P |

| removed | (mg/dL) | (ratio to | ||

| by ERCP | normal) | |||

| Total | 193 | 109 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| Abnormal CBD on USG (percent of total) | 91 (47.2) | 82 (90) | 4.2 | 2 |

| CBD dilatation | 28 (30.8) | 24 (85.7) | 4.5 | 2 |

| CBD stones | 23 (25.3) | 20 (87) | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| Both | 40 (43.9) | 38 (90) | 4 | 1.8 |

| Normal CBD on USG, | 102 (52.8) | 27 (26.5) | 3.3 | 1.4 |

| MRCP findings (percent of total) | ||||

| Normal MRCP | 70 (68.6) | 2 (2.9) | 3.2 | 1.3 |

| Stones on MRCP | 32 (31.4) | 25 (78.2) | 3.4 | 1.7 |

Normal bile ducts were detected by USG in 102 (52.8%) patients and ERCP was used to extract stones in 26.5% of them. IOC detected two patients with CBDS in the MRCP negative group (false negative 2.9%) and none in the ERCP negative group. There were seven patients with false positive MRCP where the ERCP did not detect any stones (false positive of 21%). This high percentage could be explained by the time between the MRCP and the ERCP that is about 2-3 d because of which the stones could have passed.

More importantly when looking at this group, 29/102 (28.4%) patients had a total bilirubin > 4 mg/dL which is counted as a high risk in recent guide lines (9); out these 17 (58.6%) patients did not have stones on IOC and ERCP was not conducted in this group of patients.

Stones were confirmed in 90% of the patients with an abnormal LFT and USG findings. ERCP detected stones in 24.5% of the patients with normal findings. This strategy avoided the use of MRCP in 47.2% of patients with abnormal LFT with a negative rate for the ERCP of 10% only. It also helped avoid unnecessary ERCP in 17 (58.6%) patients with total bilirubin > 4 mg/dL.

Statistical findings are shown in Table 3, where patients with abnormal USG, total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase had a significant stone prediction in a univariate analysis. After controlling for confounders in multivariate Logistic regression analysis Alkaline phosphatase and USG findings were found to be significant predictors for CBDS. However, total bilirubin was found not to be a significant predictor (Table 4).

| Presence of | Patient | US abnormal | Mean T.Bili | Mean Al-P |

| stones | (mg/dL) | (ratio to normal) | ||

| Stones | 109 (56.5) | 82 (90) | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| No stones | 84 (43.5) | 9 (10) | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 0.6 |

| P value | < 0.0001 | < 0.01 | < 0.001 | |

| Total | 193 | 91 | 3.7 | 1.7 |

| Findings | Common bile duct stones | OR1 | 95%CI1 | |

| Present | Absent | |||

| Alkaline phosphatase | ||||

| < 151 U | 10 (23.3) | 33 (76.7) | 1 | |

| 151-225 U | 37 (54.4) | 31 (45.6) | 3.1 | 7.00-9.88 |

| 226-300 U | 21 (58.0) | 15 (42.0) | 4.5 | 1.23-16.49 |

| > 300 U | 41 (89.0) | 5 (11.0) | 29.8 | 7.28-121.54 |

| Ultrasound findings | ||||

| Normal | 27 (26.5) | 75 (73.5) | 1 | |

| Dilatation | 24 (86.0) | 4 (14.0) | 19.8 | 5.41-72.42 |

| Stones | 20 (87.0) | 3 (13.0) | 14.3 | 3.53-58.17 |

| Both | 38 (95.0) | 2 (5.0) | 61 | 13.03-285.1 |

Multivariate statistical analysis found that the rise in alkaline phosphatase was a significant predictor for CBDS. It became highly significant when double the normal alkaline phosphatase value. In this case, the probability of stone detection by ERCP increased 30-fold when this enzyme level was within the normal range.

In addition, in USG findings that detected CBD dilatation and those that detected stones were both significant predictors for the presence of CBDS found by ERCP. Detection of both dilation and stones concurrently was a highly significant predictor of the presence of CBDS, which were about 60 times more likely than when USG results were normal.

CBDS can remain hidden for years, frequently passing undetected into the duodenum. When the symptoms become apparent, the presentation will likely include obstructive jaundice or more serious complications such as acute pancreatitis or cholangitis[7,25]. Preoperative detection and intervention to remove these stones is vital[8]. An increase in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels may be the only evidence of choledocholithiasis[10-12]. USG examination may confirm the presence of CBDS but cannot definitively exclude them when not detected[10]. The gold standard for treating these stones is ERCP, which has sensitivity and specificity rates both around 95%[8,11,14,26,27]. However, if the clinical, radiological, and laboratory testing indicates a low probability of choledocholithiasis, less invasive method such as MRCP should be performed first[9].

The sensitivity of transabdominal USG is low for detecting CBDS (22%-55%), but it is better at detecting CBD dilatation (sensitivity 77%-87%). For patients with abnormal LFT which USG detects CBDS, successful diagnosis of choledocholithiasis has been reported to be above 80%. Negative CBDS detection by ERCP in such patients may be related to the passage of these stones into the duodenum before the procedure[4,28,29].

The diameter of a normal bile duct is 3-6 mm. it increases by one mm every 10 years after the age of 60, causing mild dilatation in the elderly[30]. CBD greater than 8 mm in patients with an intact gallbladder is usually indicative of biliary obstruction[9]. Although no single factor strongly predicts choledocholithiasis in patients with symptomatic gallstones, many studies have shown that the probability of CBDS is higher in the presence of multiple abnormal prognostic signs. Patients with such markers are considered to be at high risk, and preoperative ERCP is indicated when there are no available facilities for performing CBD laparoscopic exploration[9-13,31-34].

In the present study, abnormal LFT results were observed in 21.5% in patients with symptomatic gallstones, a higher incidence than previously reported in the literature (15%)[35]. This discrepancy may be related to environmental (Taif is a high-altitude province), cultural or social factors[2-4,6,7]. Our facility is a tertiary hospital serving a widespread rural area.

Therefore, the routine use of MRCP as has been recommended by others for patients with abnormal LFT[17-19] is not practical or cost effective.

Among the patients involved in the study, there were 78.5% patients with normal LFT results and no CBD abnormalities detected by USG. They were therefore referred for LC without further workup, consistent with the recommendations made by the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (SPC-ASGE)[9]. The results of our study, which concluded before the publication of the 2010 guidelines, were similar, patients with symptomatic gallstones but normal LFT and USG are considered to be at low risk for choledocholithiasis. For these patients, they recommend, as we do, cholecystectomy, without further evaluation to avoid the cost and risks of additional preoperative biliary evaluation, which are not justified by the low probability of CBDS[9]. Whether or not to perform routine IOC or laparoscopic US during LC remains an area of controversy[20,21].

We found (52.8%) patients with abnormal LFT but normal CBD USG results, who were sent for MRCP examination. This group of patients is considered by the SPC-ASGE to be at intermediate risk of choledocholithiasis, and their guidelines recommend further evaluation with preoperative EUS or MRC or an IOC[9], as we do. However, they do recommend that a total bilirubin higher than 4 mg/dL, should be considered as a high probability of CBDS. In our study, we found total bilirubin to be not a significant predictor on multivariant analysis. Also, in 17 (58.6%) of the patients with high total bilirubin (> 4 mg/dL) and normal USG, CBDS was not detected by IOC in the operating room. Therefore, as per their recommendation ERCP was avoided in this group in our study.

Statistical findings revealed that a rise in bilirubin level was not a significant predictor for detecting CBDS. However, this finding should be reevaluated considering the higher incidences of hepatitis, sickle cell anemia, and secondary polycythemia (related to the high altitude) in our province. Yang et al[36] found that among the components of the LFTs, alkaline phosphatase was a better indicator for choledocholithiasis than bilirubin. However, the SPC-ASGE reported modestly better CBDS positive predictive values for bilirubin. They found cholestatic liver biochemical tests, in particular alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, increases progressively with the duration and severity of biliary obstruction.

In the present study, MRCP helped avoid unnecessary ERCP in 58.6% of patients with high total bilirubin and normal CBD USG results. It was associated with a false negative rate of 2.96% and false positive rate of 21%, similar to those reported in other studies[16,37].

Patients with abnormal LFT and USG were classified as a high risk for CBDS. By applying this algorithm, we diagnosed and treated these patients directly with ERCP and avoided the cost of MRCP and stones were extracted in 90%, with a low negative incidence of ERCP of 10%. This led to a shorter hospital stay and was even far better when some patients had the ERCP and the LC in the same sitting.

IOC has multiple advantages, as some centers use it routinely to identify the biliary anatomy and others use it for stone detection[15,16]. Its routine use is still controversial; however, in selective cases it is widely adopted. In cases where CBDS are thought of, it can be used with less cost and in the same time as the LC where it will take few minutes. However, not many general surgeons are familiar with this use, making it a less popular procedure. Therefore, its use in selective cases has been accepted. We have recommended its use in patients with negative MRCP or ERCP since these procedures have a false negative rate and discharging these patients with retained CBDS can lead to delayed acute presentation like acute pancreatitis, cholangitis and cystic duct leak[25,38].

In conclusion, we recommend the use of this simple algorithm to stratify patients into low risk when LFT and USG are normal. These patients can go for LC with no further work-up. Patients with abnormal LFT or US are stratified as intermediate risk regardless of the total bilirubin level and should undergo MRCP as the risk of ERCP is not justified. Patients with abnormal LFT and USG are stratified as high risk and should undergo ERCP and stone extraction with LC in the same sitting if possible, as the cost of MRCP and the time needed is not justified.

Symptomatic gallstones with abnormal liver function tests are seen in higher percentages in higher altitude areas. Choledocholithiasis is the commonest cause; however, it is a challenge to diagnose and treat these cases while maintaining a low cost and minimum hospital stay. In this study the authors tried to design a simple pathway to diagnose and treat this problem without the over use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatagrophy that is costly or the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography that has major side effects.

In the past all patients with common bile duct stones (CBDS) were subjected to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). This was the best way to diagnose these patients, however, there were complications like bleeding, perforation or even death with this procedure. Then magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was developed and became widely used. However, it is very costly and after the diagnosis of CBDS an ERCP was needed to remove the stone. Recently some authors have advocated the routine use of MRCP without looking in the cost or even its availability. The authors believe that it is time to reach a balance between the uses of both procedures to get the best of both when needed.

The authors have developed a simple pathway for the treatment of CBDS which has the least cost and requiring a minimal hospital stay. The authors have also found that the total bilirubin level does not play a part in the pathway as mentioned by the American Endoscopy Society.

This simple pathway can be applied in any patient care facility even if it is not very advanced. The pathway does not have any special requirements.

The manuscript is quite well written. The methods are adequate. The results justify the conclusions drawn.

P- Reviewers D'Elios MM, Malnick S S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Nakeeb A, Comuzzie AG, Martin L, Sonnenberg GE, Swartz-Basile D, Kissebah AH, Pitt HA. Gallstones: genetics versus environment. Ann Surg. 2002;235:842-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alsaif MA. Variations in dietary intake between newly diagnosed gallstone patients and controls. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition. 2005;4:1-7. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abu-Eshy SA, Mahfouz AA, Badr A, El Gamal MN, Al-Shehri MY, Salati MI, Rabie ME. Prevalence and risk factors of gallstone disease in a high altitude Saudi population. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:794-802. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Alam MK. Assessment of indicators for predicting choledocholithiasis before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;18:511-513. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Moro PL, Checkley W, Gilman RH, Cabrera L, Lescano AG, Bonilla JJ, Silva B. Gallstone disease in Peruvian coastal natives and highland migrants. Gut. 2000;46:569-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Spathis A, Heaton KW, Emmett PM, Norboo T, Hunt L. Gallstones in a community free of obesity but prone to slow intestinal transit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Browning JD, Horton JD. Gallstone disease and its complications. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003;14:165-177. [PubMed] |

| 8. | O’Neill CJ, Gillies DM, Gani JS. Choledocholithiasis: overdiagnosed endoscopically and undertreated laparoscopically. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:487-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Cash BD, Fisher L, Harrison ME, Fanelli RD, Fukami N. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Freitas ML, Bell RL, Duffy AJ. Choledocholithiasis: evolving standards for diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3162-3167. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Dumot JA. ERCP: current uses and less-invasive options. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:418, 421, 424-425 passim. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grande M, Torquati A, Tucci G, Rulli F, Adorisio O, Farinon AM. Preoperative risk factors for common bile duct stones: defining the patient at high risk in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Sattawatthamrong Y, Manatsathit S, Tanwandee T, Leelakusolvong S, Kachintorn U, Leungrojanakul P, Boonyapisit S, Pongprasobchai S. Predictive factors for synchronous common bile duct stone in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:131-136. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mori T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Gallstone disease: Management of intrahepatic stones. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1117-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Romagnuolo J, Bardou M, Rahme E, Joseph L, Reinhold C, Barkun AN. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected biliary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:547-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Verma D, Kapadia A, Eisen GM, Adler DG. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jendresen MB, Thorbøll JE, Adamsen S, Nielsen H, Grønvall S, Hart-Hansen O. Preoperative routine magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography before laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective study. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:690-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nebiker CA, Baierlein SA, Beck S, von Flüe M, Ackermann C, Peterli R. Is routine MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) justified prior to cholecystectomy? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:1005-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dalton SJ, Balupuri S, Guest J. Routine magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and intra-operative cholangiogram in the evaluation of common bile duct stones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2005;87:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Van Lith HA, Van Zutphen LF, Beynen AC. Butyrylcholinesterase activity in plasma of rats and rabbits fed high-fat diets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1991;98:339-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Massarweh NN, Flum DR. Role of intraoperative cholangiography in avoiding bile duct injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:656-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bose SM, Mazumdar A, Prakash VS, Kocher R, Katariya S, Pathak CM. Evaluation of the predictors of choledocholithiasis: comparative analysis of clinical, biochemical, radiological, radionuclear, and intraoperative parameters. Surg Today. 2001;31:117-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khalfallah M, Dougaz W, Bedoui R, Bouasker I, Chaker Y, Nouira R, Dziri C. Validation of the Lacaine-Huguier predictive score for choledocholithiasis: prospective study of 380 patients. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e66-e72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sarli L, Costi R, Gobbi S, Iusco D, Sgobba G, Roncoroni L. Scoring system to predict asymptomatic choledocholithiasis before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A matched case-control study. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1396-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chang JH, Lee IS, Lim YS, Jung SH, Paik CN, Kim HK, Kim TH, Kim CW, Han SW, Choi MG. Role of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis: analysis of patients with negative MRCP. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Christensen M, Matzen P, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Complications of ERCP: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:721-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Caddy GR, Tham TC. Gallstone disease: Symptoms, diagnosis and endoscopic management of common bile duct stones. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1085-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Contractor QQ, Boujemla M, Contractor TQ, el-Essawy OM. Abnormal common bile duct sonography. The best predictor of choledocholithiasis before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:429-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Costi R, Sarli L, Caruso G, Iusco D, Gobbi S, Violi V, Roncoroni L. Preoperative ultrasonographic assessment of the number and size of gallbladder stones: is it a useful predictor of asymptomatic choledochal lithiasis? J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:971-976. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bachar GN, Cohen M, Belenky A, Atar E, Gideon S. Effect of aging on the adult extrahepatic bile duct: a sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:879-882; quiz 883-885. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Onken JE, Brazer SR, Eisen GM, Williams DM, Bouras EP, DeLong ER, Long TT, Pancotto FS, Rhodes DL, Cotton PB. Predicting the presence of choledocholithiasis in patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:762-767. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Sugiyama E. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte-mediated effects on human oral keratinocytes by periodontopathic bacterial extracts. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;59:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 33. | Notash AY, Salimi J, Golfam F, Habibi G, Alizadeh K. Preoperative clinical and paraclinical predictors of choledocholithiasis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:304-307. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Prat F, Meduri B, Ducot B, Chiche R, Salimbeni-Bartolini R, Pelletier G. Prediction of common bile duct stones by noninvasive tests. Ann Surg. 1999;229:362-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Habib L, Mirza MR, Ali Channa M, Wasty WH. Role of liver function tests in symptomatic cholelithiasis. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009;21:117-119. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Yang MH, Chen TH, Wang SE, Tsai YF, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY, Shyr YM. Biochemical predictors for absence of common bile duct stones in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1620-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hallal AH, Amortegui JD, Jeroukhimov IM, Casillas J, Schulman CI, Manning RJ, Habib FA, Lopez PP, Cohn SM, Sleeman D. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography accurately detects common bile duct stones in resolving gallstone pancreatitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:869-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Srinivasa S, Sammour T, McEntee B, Davis N, Hill AG. Selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in clinical practice may miss choledocholithiasis in gallstone pancreatitis. Can J Surg. 2010;53:403-407. [PubMed] |