Published online Sep 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5759

Revised: July 1, 2013

Accepted: July 23, 2013

Published online: September 14, 2013

Processing time: 143 Days and 13.8 Hours

Variceal bleeding is the most serious complication of portal hypertension, and it accounts for approximately one fifth to one third of all deaths in liver cirrhosis patients. Currently, endoscopic treatment remains the predominant method for the prevention and treatment of variceal bleeding. Endoscopic treatments include band ligation and injection sclerotherapy. Injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate has been successfully used to treat variceal bleeding. Although injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate provides effective treatment for variceal bleeding, injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate is associated with a variety of complications, including systemic embolization. Herein, we report a case of cerebral and splenic infarctions after the injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate to treat esophageal variceal bleeding.

Core tip: Variceal bleeding is the most serious complication of portal hypertension, and it accounts for approximately one fifth to one third of all deaths in liver cirrhosis patients. Although injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate provides effective treatment for variceal bleeding, injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate is associated with a variety of complications including systemic embolization. Herein, we report a case of cerebral and splenic infarctions after the injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate to treat esophageal variceal bleeding.

-

Citation: Myung DS, Chung CY, Park HC, Kim JS, Cho SB, Lee WS, Choi SK, Joo YE. Cerebral and splenic infarctions after injection of

N -butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in esophageal variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(34): 5759-5762 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i34/5759.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5759

Variceal bleeding is a catastrophic complication of liver cirrhosis. Although the short-term mortality of variceal bleeding has improved due to recent advances in treatment, the long-term outcomes remain guarded.

Currently, endoscopic treatment remains the predominant method for prevention and treatment of variceal bleeding. Endoscopic treatments include band ligation and injection sclerotherapy. Injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl, B-Braun Surgical GmbH, Melsungen, Germany) has been successfully used for variceal bleeding, but Histoacryl injection is associated with a variety of complications, some of which can be disastrous[1].

Systemic embolization including the cerebrum, lung, spleen, and portal vein is a rare and serious complication of Histoacryl injection that has been principally described in the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding[2,3]. However, this complication following the esophageal variceal injection of Histoacryl is extremely rare. To date, few cases of this complication at one site have been reported in the English literature.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of multiple embolizations including the cerebrum and spleen after Histoacryl injection in esophageal variceal bleeding.

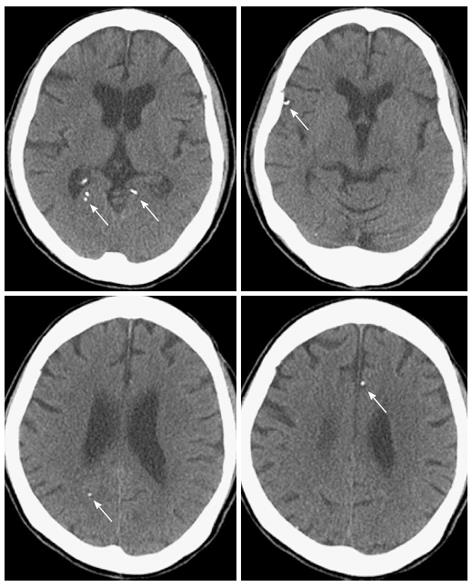

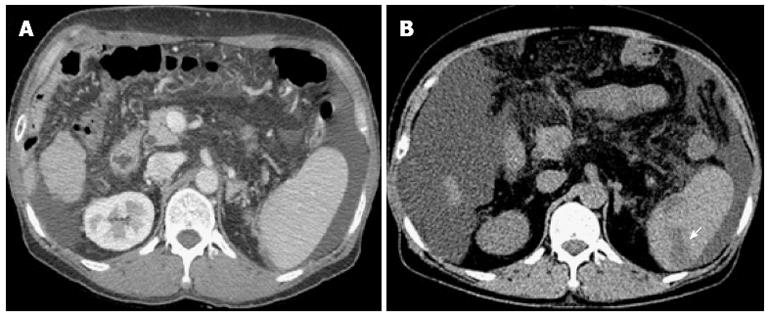

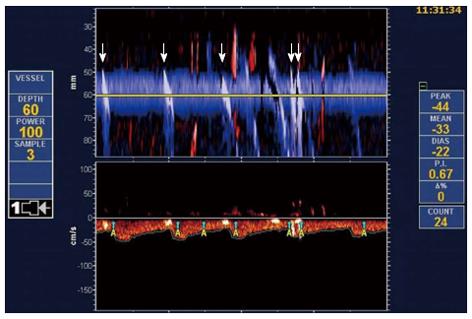

A 55-year-old woman with alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis of Child-Pugh class B was admitted to Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital (Jeonnam, South Korea) with a 1-d history of hematemesis. She denied prior gastrointestinal bleeding, peptic ulcer diseases, and use of ulcerogenic medications. On admission, she had a pulse of 90 beats/min, a blood pressure of 80/50 mmHg, and a respiratory rate of 30 breaths/min. The head and neck examination was normal, except for anemic conjunctiva. She had florid spider angiomata. The abdomen was nontender with ascites, and the spleen tip was slightly palpable. Rectal examination demonstrated the presence of maroon-colored, liquid stool. Laboratory studies revealed the following: hemoglobin, 8.2 g/dL (normal range, 12-18 g/dL); hematocrit, 24.8% (37%-52%); white blood cell count, 9300/mm3 (4000-10800/mm3); platelet count, 100000/mm3 (130000-450000/mm3); total protein, 5.1 g/dL (5.8-8.1 g/dL); albumin, 2.3 g/dL (3.1-5.2 g/dL); total bilirubin, 1.4 mg/dL (0.3-1.3 mg/dL); aspartate aminotransferase, 90 U/L (7-38 U/L); and alanine aminotransferase, 8 U/L (6-42 U/L). Her coagulation profiles were prothrombin time 19.6 s (11-14.9 s) and activeated partial thromboplastin time 34.5 s (28-40 s). Endoscopy showed a large esophageal varix with a fibrin plug (Figure 1). Because the bleeding esophageal varix was too large to apply band ligation, we performed injection sclerotherapy with a mixture of Histoacryl and Lipiodol (Laboratoire Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France). The mixture was injected intra-variceally using a 21-gauge needle injector (Injector Force, NM-200L-0821, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The mixture consisted of 0.5 mL of Histoacryl and 0.5 mL of Lipiodol. Because variceal bleeding was not controlled after the first injection, a second injection was performed in the same manner. After the second injection, variceal bleeding was controlled. The total injected volume was 2 mL. However, she developed dysarthria and right motor weakness (grade III/V) 1 h after the injection. Brain computed tomography (CT) showed multiple hyperdense foci in the frontal lobe and the parieto-occipital lobe (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed acute multifocal cortical infarctions. Abdominal CT revealed several wedge-shaped, low attenuation lesions in the spleen, indicating infarction (Figure 3). To evaluate the cause of the newly developed cerebral and splenic infarctions, a transcranial Doppler (TCD) bubble test was performed. The TCD bubble test is used to detect a right-to-left shunt. We used 2 MHz M-mode TCD (ST3, Spencer Technologies, Seattle, Washington, United States; SONARA, Viasys Healthcare, Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, United States) to detect microbubbles in the middle cerebral artery. TCD demonstrated the presence of a microbubble on the M-mode displays in the middle cerebral artery. TCD using Spencer Logarithmic Scale Grades was indicative of grade III during resting and grade IV during the Valsalva maneuver (Figure 4). In the Spencer Logarithmic Scale Grades, grade I and II are considered negative for patent foramen ovale, and grades III through V are considered positive. These findings indicate that the patient had a patent foramen ovale. Therefore, cerebral and splenic infarctions may develop due to emboli cause by a right-to-left shunt. At the follow-up examination, her neurologic symptoms were improved, but neurologic sequelae remained.

Endoscopic treatments, such as band ligation and injection sclerotherapy, became the cornerstone of the management of variceal bleeding. Endoscopic band ligation is the preferred form of endoscopic treatment for esophageal variceal bleeding, but its application in actively bleeding patients is still challenging because the bands at the endoscope tip limit the operator’s field of vision. Injection sclerotherapy with various sclerosants is recommended in patients in whom endoscopic band ligation is not technically feasible. Several sclerosants are available, including 5% sodium morrhuate, 1%-3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate, 5% ethanolamine oleate, and 0.5%-1% polidocanol[2]. Adhesives such as Histoacryl have been used successfully for the treatment of variceal bleeding.

Injection sclerotherapy provides effective treatment for variceal bleeding, but it has been associated with a variety of complications. Minor complications including chest pain, dysphagia, fever, and esophageal ulcer are common, although not typically serious. Uncommon and serious complications include bacteremia, esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and brain abscess. Rarely, systemic embolic complications have followed injection sclerotherapy, and these can be disastrous[4]. Systemic embolic complications following Histoacryl injection have been reported, and the common sites of embolic complications were the lung, spleen, cerebrum, and portal vein. Additionally, this complication has been principally described in the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding. Because most gastric varices are associated with a gastrorenal and splenorenal shunts[5], blood flow is abundant, and Histoacryl injection is likely to cause systemic embolization due to the migration of the agent through a shunt[6]. In contrast to gastric variceal injection, systemic embolic complications arising from esophageal variceal injection sclerotherapy are extremely rare; to date, only three cases of cerebral embolic complications following esophageal variceal injection sclerotherapy have been documented in the literature[7,8].

Because the bleeding esophageal varix was too large to apply band ligation, we performed injection sclerotherapy with Histoacryl. Cerebral and splenic infarctions followed the bleeding esophageal variceal injection sclerotherapy. Ours is an additional case of cerebral infarction caused by the esophageal variceal injection of Histoacryl, although it is the first report of a case of multiple embolizations including the cerebrum and spleen after the esophageal variceal injection of Histoacryl. The possible explanation for the development of systemic emboli may be the transient patent foramen ovale caused by the episodes of coughing, which induced a temporary right-to-left shunt.

Clearly, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is considered the gold standard for right-to-left shunt diagnosis, but it is poorly tolerated by patients and sometimes requires sedation. Additionally, TEE limits the patient’s ability to perform a Valsalva maneuver[9]. Because our case had a large esophageal varix, we performed a TCD bubble test rather than TEE. The TCD bubble test has proven to be a trustworthy and less invasive method for diagnosing a right-to-left shunt[10]. In our case, the ultrasound waves were reflected by microbubbles on the TCD bubble test, indicating the patent foramen ovale. Additionally, the TCD bubble test was grade III during resting and grade IV during the Valsalva maneuver, according to the Spencer Logarithmic Scale[8]. Therefore, the cerebral and splenic infarctions in our case may have been caused by emboli via the patent foramen ovale.

Factors that increase embolization risk include the size of varices, the presence of a collateral vessel, excessive dilution, rapid polymerization, large volume (> 1 mL/injection) and rapid Histoacryl injection. Our case had the three possible embolic risk factors including the large size of the varices, the large volume (> 1 mL) of the mixture injected, and rapid injection[6]. Because most embolization risks associated with Histoacryl, as described above, are preventable, proper injection technique may help minimize the risk of serious complications and improve the long-term outcome.

Taken together, although injection sclerotherapy with Histoacryl is a relatively safe and efficacious procedure for the treatment of variceal bleeding, serious complications such as systemic embolization can occur. Ours is the first report of a case of multiple embolizations including the cerebrum and spleen after Histoacryl injection to treat esophageal variceal bleeding. Systemic embolization, despite its rarity, should be considered among the serious complications of Histoacryl injection for the treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding.

P- Reviewers Higuchi K, Koulaouzidis A, Yang YS S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Schuman BM, Beckman JW, Tedesco FJ, Griffin JW, Assad RT. Complications of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:823-830. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Helmy A, Hayes PC. Review article: current endoscopic therapeutic options in the management of variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:575-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Habib SF, Muhammad R, Koulaouzidis A, Gasem J. Pulmonary embolism after sclerotherapy treatment of bleeding varices. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:91-93. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Habib A, Sanyal AJ. Acute variceal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:223-252, v. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ryan BM, Stockbrugger RW, Ryan JM. A pathophysiologic, gastroenterologic, and radiologic approach to the management of gastric varices. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1175-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matsumoto A, Takimoto K, Inokuchi H. Prevention of systemic embolization associated with treatment of gastric fundal varices. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abdullah A, Sachithanandan S, Tan OK, Chan YM, Khoo D, Mohamed Zawawi F, Omar H, Tan SS, Oemar H. Cerebral embolism following N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for esophageal postbanding ulcer bleed: a case report. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sée A, Florent C, Lamy P, Lévy VG, Bouvry M. Cerebrovascular accidents after endoscopic obturation of esophageal varices with isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate in 2 patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1986;10:604-607. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Spencer MP, Moehring MA, Jesurum J, Gray WA, Olsen JV, Reisman M. Power m-mode transcranial Doppler for diagnosis of patent foramen ovale and assessing transcatheter closure. J Neuroimaging. 2004;14:342-349. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sarkar S, Ghosh S, Ghosh SK, Collier A. Role of transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in stroke. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:683-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |