Published online Sep 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5750

Revised: March 7, 2013

Accepted: March 22, 2013

Published online: September 14, 2013

Processing time: 237 Days and 8.4 Hours

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a systemic granulomatous disease caused by fungus, and must be considered in the differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal tumors in endemic areas. We report a rare case of paracoccidioidomycosis in the pancreas. A 45-year-old man was referred to our institution with a 2-mo history of epigastric abdominal pain that was not diet-related, with night sweating, inappetence, weight loss, jaundice, pruritus, choluria, and acholic feces, without signs of sepsis or palpable tumors. Abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed a solid mass of approximately 7 cm × 5.5 cm on the pancreas head. Abdominal computerized tomography showed dilation of the biliary tract, an enlarged pancreas (up to 4.5 in the head region), with dilation of the major pancreatic duct. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, and the surgical description consisted of a tumor, measuring 7 to 8 cm with a poorly-defined margin, adhering to posterior planes and mesenteric vessels, showing an enlarged bile duct. External drainage of the biliary tract, Roux-en-Y gastroenteroanastomosis, lymph node excision, and biopsies were performed, but malignant neoplasia was not found. Microscopic analysis showed chronic pancreatitis and a granulomatous chronic inflammatory process in the choledochal lymph node. Acid-alcohol resistant bacillus and fungus screening were negative. Fine-needle aspiration of the pancreas was performed under US guidance. The smear was compatible with infection by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. We report a rare case of paracoccidioidomycosis simulating a malignant neoplasia in the pancreas head.

Core tip: This is a report of a rare case of pancreatic paracoccidioidomycosis, which shows its importance in the differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal tumors in endemic areas. This is apparently the first such report written in English. The patient had a pancreatic mass adhering to vessels and deep planes, with enlargement of satellite lymph nodes; but malignant neoplasia was not found. The ultrasonography-guided pancreas fine-needle aspiration defined the diagnosis and successfully directed the therapy. Remarkably, although the patient had abdominal lymph node enlargement, he did not present peripheral lymphadenopathy, which is usually the major complaint in patients with the juvenile form of paracoccidioidomycosis.

- Citation: Lima TB, Domingues MAC, Caramori CA, Silva GF, Oliveira CV, Yamashiro FDS, Franzoni LC, Sassaki LY, Romeiro FG. Pancreatic paracoccidioidomycosis simulating malignant neoplasia: Case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(34): 5750-5753

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i34/5750.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5750

Paracoccidioidomycosis (also known as Pb mycosis or South American blastomycosis) is a systemic granulomatous disease caused by the fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis[1], which is autochthonous in Latin America. It was described by Lutz[2], and its incidence ranges from 3 to 4 cases per million, up to 1 to 3 cases per one hundred thousand inhabitants per year in endemic areas, with an annual mortality of 1.45 per million inhabitants, which is the highest rate observed among systemic mycoses[1]. It affects 10 to 15 adult males per one female case, mostly between the 3rd and 6th decades of life, and has two main forms: the juvenile form, constituting 3%-5% of cases, which compromises the reticuloendothelial system, and the somewhat more common chronic form that comprises 90% of cases, mainly affecting the skin and the lungs[1]. Paracoccidioidomycosis can mimic neoplasias, such as periampullary[3] or colon[4] cancer. Therefore, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal tumors in endemic areas[5]. This case illustrates a rare case of paracoccidioidomycosis simulating a malignant neoplasia in the pancreas head.

A 45-year-old white adult male from São Paulo state was referred to our institution with a 2-mo history of epigastric pain that was not diet-related. It was intermittent, of strong intensity, with radiation to the back and relieved by the use of omeprazole. Additionally, the patient had night sweating and a weight loss of 13 kg in 45 d, and lacked vomiting, diarrhea, or fever. Twenty days before admission, the patient reported jaundice, pruritus over the whole body, choluria, and acholic feces. The patient was a current smoker and alcohol user, while his physical examination revealed jaundice and pain after deep abdominal palpation, without signs of sepsis or palpable tumors. Pulmonary auscultation showed no alterations, and laboratory exams confirmed cholestatic syndrome (Table 1).

| Admission | 3 mo | 12 mo | Normal range | |

| GGT (U/L) | 646 | 677 | 632 | 15-73 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 1047 | 600 | 262 | 36-126 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) | 58 | 147 | 68 | 30-110 |

| Alanine transferase (U/L) | 53 | 184 | 173 | 21-75 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.5 | 4.3 | 4.8 | 3.5-5 |

| INR | 1.04 | 1.17 | 1.12 | < 1.25 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.8 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.2-1.3 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0-1.1 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0-0.3 |

| Platelets (× 103/mm3) | 278 | 177 | 138 | 140-440 |

| Leukocytes (× 103/mm3) | 6.2 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 4-11 |

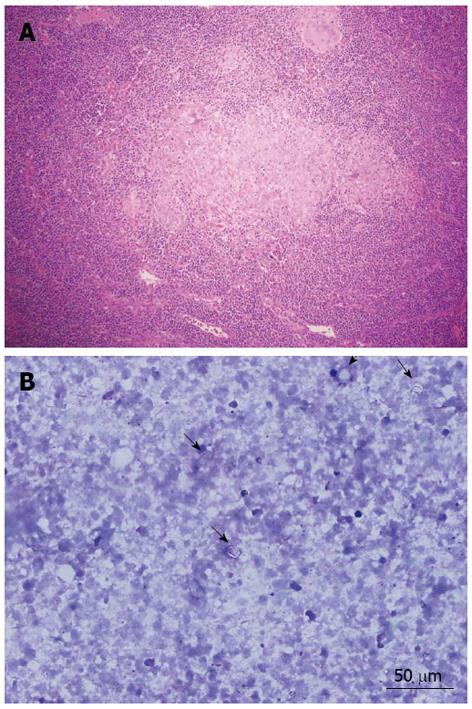

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) showed a solid mass of approximately 7 cm × 5.5 cm on the pancreas head, with a small tumor of 1 to 2 cm juxtaposed with the mass, suggesting local metastases. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) showed dilation of the biliary tract, an enlarged pancreas (up to 4.5 in the region of the head) with a poorly-defined margin and two hypodense areas without significant enhancement after intravenous contrast, leading to dilation of the major pancreatic duct, but without retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Due to the momentary unavailability of the necessary equipment at our institution to perform a puncture guided by CT or US, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. The surgical description consisted of a pancreatic tumor measuring 7 to 8 cm with a poorly-defined margin, adhering to posterior planes and to mesenteric vessels, and showing an enlarged bile duct. Transcystic cholangiography showed obstruction of the passage of contrast through the distal bile duct, which was compatible with extrinsic compression. External drainage of the biliary tract, Roux-en-Y gastroenteroanastomosis, lymph node excision, and biopsies were performed. Malignant neoplasia was not found at the intraoperative frozen section analysis. Microscopic analysis showed chronic pancreatitis and a granulomatous chronic inflammatory process in the choledochal lymph node. The presence of granulomas without caseous necrosis in the lymph node would suggest a diagnosis of sarcoidosis; however, at that time it was not possible to definitively discard the diagnosis of tuberculosis (Figure 2A). Acid-alcohol resistant bacillus and fungus screening by Ziehl-Neelsen, PAS, and Gömöri staining were negative. The biopsies were reviewed, and a cohesive granuloma without caseous necrosis was found attached to peripancreatic fat. The abdominal pain and the jaundice worsened, and the patient developed fever, leukocytosis, and drainage of purulent secretion by a surgical drain located near the pancreas. Upper digestive endoscopy showed esophageal varices. Plain chest X-ray and thoracic CT scan were normal. Metronidazole and ciprofloxacin were prescribed due to the hypothesis of bacterial cholangitis, and clinical improvement was observed. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the pancreas was performed with US guidance. The obtained smear was compatible with infection by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Figure 2B). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests, employed for the detection of anti-Paracoccidioides brasiliensis antibodies, produced positive results (titers of 1/8 and 1/16). Intravenous sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (800/160 mg two times per day) was introduced, after which the patient showed clinical and laboratory improvement (Table 1).

Pancreatic paracoccidioidomycosis simulating pancreatic neoplasia has been infrequently reported in the literature[6]. Clinical findings include weight loss, weakness, dizziness, repletion, pruritus, jaundice, choluria, and fecal acholia, as in the reported case. Signs of cholestatic disease are the most reported abnormalities, with an increase in alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transferase. Jaundice is usually observed in the late stage of the disease, and is associated with differential diagnoses of greater severity[7], such as malignant pancreatic neoplasia. The findings of pancreatic tumor adhering to vessels and deep planes, as well as satellite nodules and obstruction of the biliary tract with secondary portal hypertension (diagnosed through the esophageal varices), suggested a diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic cancer. As shown in this report, abdominal lymphatic compromise may give rise to such clinical conditions as abdominal tension and pain, which may even simulate acute abdomen affections[8]. The granulomatous involvement of lymph nodes initially led to the hypothesis of sarcoidosis, which may affect multiple organs, particularly the lungs (90%) and lymph nodes (75%)[9]. But sarcoidosis rarely affects the pancreas[10,11], and when it does, it is usually asymptomatic[12]. The type of granuloma found in the lymph node, characteristically epithelioid, without necrosis or bacilli, favored this diagnosis. On the other hand, immunosuppression with corticoids, which would be recommended in a case of sarcoidosis, may be harmful if the patient has had an infectious disease. At that time, the second pancreatic tissue sample obtained by FNA defined the paracoccidioidomycosis diagnosis and successfully directed the therapy. Interestingly, although the patient had had an abdominal lymph node enlargement, he did not have peripheral lymphadenopathy, which is usually the major complaint in patients with the juvenile form of paracoccidioidomycosis. Additionally, there were none of the pulmonary manifestations that occur in 90% of patients with the chronic form[1]. Although it is rare, pancreatic paracoccidioidomycosis must be considered in the differential diagnosis of intra-abdominal tumors in endemic areas, even without peripheral lymphadenopathy.

P- Reviewer Sumi S S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Telles Filho Fde Q, Mendes RP, Colombo AL, Moretti ML. [Guidelines in paracoccidioidomycosis]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:297-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lutz A. Uma mycose pseudococcidica localizada na bocca e observada no Brazil. Contribuição ao conhecimento das hyphoblastomycoses americanas. Brasil Med. 1908;22:121-124, 141-144. |

| 3. | Paganini CB, Ferreira AB, Minanni CA, Lopes de Pontes FE, Ribeiro C, Silva RA, Pacheco AM, de Moricz A, De Campos T. Blastomycosis: a differential diagnosis of periampullary tumors. Pancreas. 2010;39:1120-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chojniak R, Vieira RA, Lopes A, Silva JC, Godoy CE. Intestinal paracoccidioidomycosis simulating colon cancer. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:309-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prado FL, Prado R, Gontijo CC, Freitas RM, Pereira MC, Paula IB, Pedroso ER. Lymphoabdominal paracoccidioidomycosis simulating primary neoplasia of the biliary tract. Mycopathologia. 2005;160:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Trad HS, Trad CS, Elias Junior J, Muglia VF. Revisão radiológica de 173 casos consecutivos de paracoccidioidomicose. Radiol Bras. 2006;39:175-179. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chaib E, de Oliveira CM, Prado PS, Santana LL, Toloi Júnior N, de Mello JB. Obstructive jaundice caused by blastomycosis of the lymph nodes around the common bile duct. Arq Gastroenterol. 1988;25:198-202. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Grossklaus Dde A, Tadano T, Breder SA, Hahn RC. Acute disseminated paracoccidioidomycosis in a 3 year-old child. Braz J Infect Dis. 2009;13:242-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sharma OP. Sarcoidosis: clinical, laboratory, and immunologic aspects. Semin Roentgenol. 1985;20:340-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wijkstrom M, Bechara RI, Sarmiento JM. A rare nonmalignant mass of the pancreas: case report and review of pancreatic sarcoidosis. Am Surg. 2010;76:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Harder H, Büchler MW, Fröhlich B, Ströbel P, Bergmann F, Neff W, Singer MV. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis of liver and pancreas: a case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2504-2509. [PubMed] |