Published online Sep 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5738

Revised: July 28, 2013

Accepted: August 16, 2013

Published online: September 14, 2013

Processing time: 86 Days and 8.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) by conducting a meta-analysis.

METHODS: Electronic databases were searched for studies investigating efficacy and/or tolerability of herbal medicines in the management of different types of IBD. The search terms were: “herb” or “plant” or “herbal” and “inflammatory bowel disease”. Data were collected from 1966 to 2013 (up to Feb). The “clinical response”, “clinical remission”, “endoscopic response”, “endoscopic remission”, “histological response”, “histological remission”, “relapse”, “any adverse events”, and “serious adverse events” were the key outcomes of interest. We used the Mantel-Haenszel, Rothman-Boice method for fixed effects and DerSimonian-Laird method for random-effects. For subgroup analyses, we separated the studies by type of IBD and type of herbal medicine to determine confounding factors and reliability.

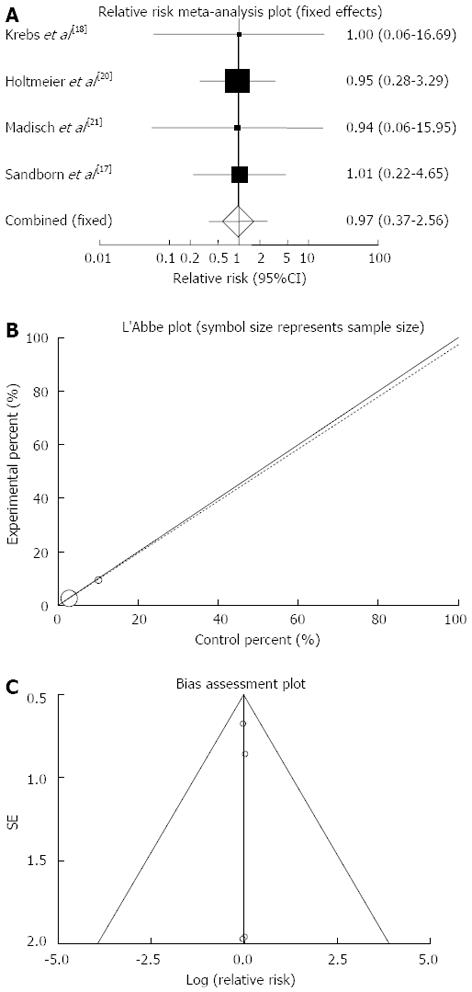

RESULTS: Seven placebo controlled clinical trials met our criteria and were included (474 patients). Comparison of herbal medicine with placebo yielded a significant RR of 2.07 (95%CI: 1.41-3.03, P = 0.0002) for clinical remission; a significant RR of 2.59 (95%CI: 1.24-5.42, P = 0.01) for clinical response; a non-significant RR of 1.33 (95%CI: 0.93-1.9, P = 0.12) for endoscopic remission; a non-significant RR of 1.69 (95%CI: 0.69-5.04) for endoscopic response; a non-significant RR of 0.64 (95%CI: 0.25-1.81) for histological remission; a non-significant RR of 0.86 (95%CI: 0.55-1.55) for histological response; a non-significant RR of 0.95 (95%CI: 0.52-1.73) for relapse; a non-significant RR of 0.89 (95%CI: 0.75-1.06, P = 0.2) for any adverse events; and a non-significant RR of 0.97 (95%CI: 0.37-2.56, P = 0.96) for serious adverse events.

CONCLUSION: The results showed that herbal medicines may safely induce clinical response and remission in patients with IBD without significant effects on endoscopic and histological outcomes, but the number of studies is limited to make a strong conclusion.

Core tip: Meta-analysis of seven controlled trials involving 474 patients demonstrated that herbal medicines may safely induce clinical response and remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease without significant effects on endoscopic and histological outcomes. The results of sub-analyses based on plant type demonstrated that induction of clinical remission was obtained only by Artemisia absinthium and Boswellia serrata and induction of clinical response was gained by only Aloe vera and Triticum Aestivum. Boswellia serrata in one study evaluating recurrence rate did not cause prevention of relapse. Induction of adverse events by none of the plants was significant compared to that of placebo.

- Citation: Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Induction of clinical response and remission of inflammatory bowel disease by use of herbal medicines: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(34): 5738-5749

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i34/5738.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5738

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of gastrointestinal tract with two major types including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) and some atypical forms like collagenous colitis and intractable colitis. Many etiological factors have been implicated to play role in IBD; the most important one is immunological disturbances. Different drug categories are used for the management of IBD like aminosalicylates[1], corticosteroids[2], anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs[3,4], antibiotics[5,6], probiotics[7,8], and immunosuppressants[9]. Because of lack of desirable efficacy and poor tolerability of these drugs, approach toward complementary and alternative medicines especially herbal medicines for the management of IBD are increasing[10,11]. Besides many in vivo studies[12-14], the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines in IBD have been investigated through several clinical trials. In this paper, all of these clinical trials were retrieved and a meta-analysis was performed to obtain conclusive results about efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines for the management of IBD.

The procedures performed in this meta-analysis are in accordance with recent guidelines for the reporting of meta-analysis (PRISMA guidelines).

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched for studies evaluating efficacy and/or tolerability of herbal medicines in any types of IBD. Data were collected from 1966 to 2013 (up to Feb). The search terms were: “herb” or “plant” or “herbal” and “inflammatory bowel disease”. There was no language restriction. The reference list from retrieved articles was also reviewed for additional applicable studies.

Controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and/or tolerability of herbal medicines in patients with any types of IBD were considered. The “clinical response”, “clinical remission”, “endoscopic response”, “endoscopic remission”, “histological response”, “histological remission”, “relapse”, “any adverse events”, and “serious adverse events” were the key outcomes of interest. All published studies as well as abstracts presented at meetings were evaluated. Two reviewers independently examined the title and abstract of each article to eliminate duplicates, reviews, case studies, and uncontrolled trials.

The reviewers independently extracted data on patients’ characteristics, therapeutic regimens, dosage, trial duration, and outcome measures. There was no disagreement between reviewers.

Jadad score, which indicates the quality of the studies based on their description of randomization, blinding, and dropouts (withdrawals) was used to assess the methodological quality of trials[15]. The quality scale ranges from 0 to 5 points with a low quality report of score 2 or less and a high quality report of score at least 3.

Data from selected studies were extracted in the form of 2 × 2 tables by study characteristics. Included studies were weighted and pooled. Data were analyzed using StatsDirect software version 2.7.9. RR and 95%CI were calculated using Mantel-Haenszel, Rothman-Boice (for fixed effects) or Der Simonian-Laird (for random effects) methods. The Cochran Q test was used to test heterogeneity and P < 0.05 considered significant. In case of heterogeneity or few included studies, the random effects model was used. Funnel plot was used as publication bias indicator.

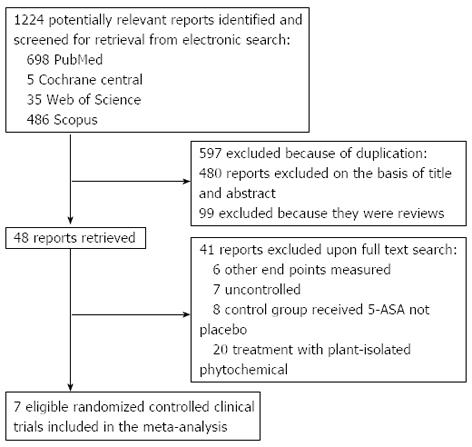

The electronic searches yielded 1224 items; 698 from PubMed, 5 from Cochrane Central, 35 from Web of Science, and 355 from Scopus. Of those, 41 trials were scrutinized in full text.

Thirty four reports were considered ineligible. Thus, 7 trials were included in the analysis represented 474 patients (Figure 1)[16-22]. From these 7 studies, 5 obtained Jadad score of 4 or more[16,17,20-22] and remaining two gained Jadad score of 2[18,19] (Table 1). Among studies included, 3 investigated the efficacy and/or tolerability of herbal medicines in CD[18-20], 3 in UC[16,17,22] and 1 in collagenous colitis[21]. Five plants were investigated in 7 included studies: Aloe vera[16], Andrographis paniculata[17], Artemisia absinthium[18,19], and Boswellia serrata[20,21], and Triticum aestivum[22]. Induction of treatment was investigated in six studies and duration of these studies is between 4 and 10 wk[16-19,21,22]. Maintenance of remission was evaluated in one study and duration of this study was 52 wk[20]. Scientific name of plant(s) used in herbal medicine, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, interventions, concomitant medications, patients’ characteristics, duration of study and definition of outcomes investigated in each included study have been shown in Table 1. Results of investigated outcomes for each included study have been demonstrated in Table 2.

| Study | Scientific name of plant(s) | Study design | Method of randomization | Blindness | Withdrawal | Jadad score | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Interventions | Concomitant medications | Duration | Outcomes |

| Sandborn et al[17] | Andrographis paniculata | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | Block randomization schedule | Double-blind | 32 patients in Andrographis group and 11 in placebo group | 4 | Patients with at least 18 yr of age and confirmed diagnosis of mildly to moderately active UC (Mayo Score of 4-10 points and endoscopic subscore of at least 1) while receiving either oral mesalamine (or equivalent medications sulfasalazine, balsalazide, and olsalazine) for at least 4 wk or no medical therapy | Patients with CD or indeterminate colitis, severe UC (Mayo Score of 11 or 12 points, toxic mega-colon, toxic colitis), previous colonic surgery or probable requirement for intestinal surgery within 12 wk, enteric infection within 2 wk, a history of tuberculosis, a positive chest X-ray or tuberculin protein-purified derivative skin test, active infection with hepatitis B or any infection with hepatitis C, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, cancer within 5 yr, inadequate bone marrow, hepatic, or renal function, a history of alcohol or drug abuse that would interfere with the study, significant concurrent medical diseases, allergy to plants in the Acanthacea family, women who were pregnant or breastfeeding , receiving oral or rectal steroids within 1 mo, rectal mesalamine within 1 wk, antibiotics within 2 wk, or azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, anti-tumor necrosis factor agents, or immunosuppressive therapy within 6 wk | Group 1: Capsules containing 1200 or 1800 mg Andrographis paniculata ethanol extract. [n = 149 (male/female: 81/68)]. 1 cap tds | Mesalazine | 8 wk | (1) Clinical response (a decrease from baseline in the total Mayo Score by at least 3 points and at least 30% with an accompanying decrease in rectal bleeding subscore of at least 1 point or a absolute rectal bleeding subscore of 0 or 1 point ); (2) Clinical remission (a total Mayo Score of 2 points or lower, with no individual subscore exceeding 1 point); (3) Mucosal healing (a decrease from baseline in the endoscopy subscore by at least 1 point and an absolute endoscopy subscore of 0 or 1 point) |

| Group 2: The same capsules without herbal extract. [n = 75 (male/female: 41/34)]. 1 cap tds | ||||||||||||

| Holtmeier et al[20] | Boswellia serrata | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | A computer generated randomization scheme: In blocks of four | Double-blind | 9 patients in Boswellia group and 7 in control group | 4 | Outpatients between 18 and 75 yr with a history of CD currently in remission with at least two documented relapses during the last 4 yr, one within the last 18 mo, or a recent resection (fibrotic strictures without inflammation were not considered a relapse); CDAI < 150 and no symptoms suspicious of activity for the previous 28 d | CDAI of > 150 at screening and at baseline visit (≥ 28 d apart); severe fistulizing CD; abscesses; symptomatic stenoses; any condition that places the patient at an undue risk; surgical bowel resections within 3 mo, short bowel syndrome; total proctocolectomy; serious infections, nutritionally compromised patients requiring enteral or parenteral therapy; severe hypertension, chronic liver disorder; impaired renal function; myocardial infarction < 3 mo, cerebral blood flow disturbances or cerebral infarction < 6 mo; any history of malignancy within the past 5 yr (except for squamous or basal cell carcinoma of the skin); subjects with severe psychiatric illnesses, inability to give informed consent; and history of severe alcoholism and drug abuse; taken monoclonal antibody therapy (e.g., infliximab) within 12 mo, immunosuppressives (azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, methotrexate) within 4 mo, or corticosteroids, mesalamine/sulfasalazine, or Boswellia serrata within 6 wk prior to randomization | Group 1: Capsules containing 400 mg 8% ethanol extract of Boswellia serrata resin. [n = 42 (male/female: 13/29)]. 2 caps tds | ND | 52 wk | (1) Maintenance of remission (maintenance of CDAI < 150 throughout study); (2) Relapse (relapse was defined as both a CDAI score > 150 points and an increase in the CDAI score of ≥ 70 points) |

| Group 2: The same capsules without herbal extract. [n = 40 (male/female: 15/25)]. 2 caps tds | ||||||||||||

| Krebs et al[18] | Artemisia absinthium | Randomized, open label | ND | Unblinded | Not any | 2 | Patients between 18 and 80 yr with CDAI ≥ 200 at least for 3 mo receiving CD treatments with 5-aminosalicylates stable dose for at least 4 wk, azathioprine stable dose for 8 wk, methotrexate stable dose for 6 wk or steroids with stable dose in the range of 20-30 mg (equivalent to dexamethasone) | Treatment with TNF-α inhibitors such as infliximab; Patients with serious pathological findings in ECG, liver, kidney and heart functions, or coexisting organic diseases such as a history of cancer, asthma or other autoimmune disease, or pregnancy; any condition that in the investigators opinion placed the patient at undue risk by participating in the study; parasites in the patient’s stools, positive Clostridium difficile toxin test and active fungal or viral infection | Group 1: Capsules containing 250 mg leave and stem powder of Artemisia bsinthium. [n = 10 (male/female: 6/4)]. 3 caps tds | Azathioprine, mesalazine | 6 wk | Response: a decrease in the CDAI score of at least 70 points from the qualifying score, or a decrease in 30% of CDAI score from the baseline score |

| Group 2: No medication. [n = 10 (male/female: 3/7)] | ||||||||||||

| Madisch et al[21] | Boswellia serrata | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind | Groups of four patients according to a central computer-generated randomization list | Double-blind | 5 patients in Boswellia group | 5 | Patients, aged between 18 and 80 yr were eligible for the study if they had at least five liquid or soft stools per day on average per week, a complete colonoscopy performed within the last 4 wk before randomization, and a histologically confirmed diagnosis of collagenous colitis | Treatment with budesonide, salicylates, steroids, prokinetics, antibiotics, ketoconazole, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs within 4 wk before randomization, other endoscopically or histologically verified causes for diarrhea, infectious diarrhea, pregnancy or lactation, previous colonic surgery, and known intolerance to Boswellia extract | Group 1: 400 mg capsules containing boswellia serrata extract standardized to 80% boswellic acids, 1 capsule tid | Loperamide was allowed for the first 3 wk but was not allowed for the last 3 wk of the study. Patients were allowed to use butylscopolamine in case of abdominal pain | 6 wk | Clinical remission (stool frequency equal to or less than three soft or solid stools per day on average during the last week of treatment) |

| Group 2: Identical placebo capsules, 1 capsule tid | ||||||||||||

| Omer et al[19] | Artemisia absinthium | Double-blind, placebo-controlled | ND | Double-blind | ND | 2 | Patients between 18 and 80 yr with CDAI ≥ 200 at least for 3 mo receiving CD treatments with 5-aminosalicylates stable dose for at least 4 wk, azathioprine stable dose for 8 wk, methotrexate stable dose for 6 wk or corticosteroids (prednisolone, prednisone or budesonide) at the equivalent of 40 mg/d of prednisone or Less stable dose for 3 wk | Treatment with infliximab; patients with serious pathological findings in ECG, liver, kidney and heart functions, or coexisting organic diseases such as a history of cancer, asthma or other autoimmune disease, or pregnancy; any condition that in the investigators opinion placed the patient at undue risk by participating in the study; parasites in the patient’s stools, positive Clostridium difficile toxin test and active fungal or viral infection | Group 1: Capsules containing 250 mg leave and stem powder of Artemisia bsinthium. [n = 20 (male/female: 12/8)]. 3 caps bid | Glucocorticoids, 5-aminosalicylates, azathioprines, methotrexate | 10 wk | A decrease in the CDAI score of at least 70 points from the qualifying score, or a decrease in 30% of CDAI score from the baseline score |

| Group 2: The same capsules without Artemisia absinthium. [n = 20 (male/female: 11/9)]. 3 caps bid | ||||||||||||

| Langmead et al[16] | Aloe vera | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Computer-generated, block-design, in 2:1 ratio | Double-blind | 6 patients in aloe group and 3 in the placebo group | 4 | Age of 18-80 yr, mildly to moderately active UC (as defined by a modified SCCAI ≥ 3) and no recent changes in conventional prophylactic therapy | Acute severe UC requiring hospital admission (SCCAI > 12); inactive disease (SCCAI < 3); positive stool examination for pathogens; CD or indeterminate colitis; use of antibiotics, warfarin, cholestyramine, sucralfate, anti-diarrhoeal drugs (loperamide, codeine phosphate, diphenoxylate), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin > 75 mg/d, aloe vera or other herbal remedies; alcohol or drug abuse; pregnancy or breast feeding; female of child-bearing age not taking adequate contraception; participation in another drug trial in the previous 3 mo; and serious liver, renal, cardiac, respiratory, endocrine, neurological or psychiatric illness, alteration in their dosage of aminosalicylates in the previous 4 wk, had taken > 10 mg/d or had altered oral prednisolone dosage in the previous 4 wk, changed their dose of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine in the previous 3 mo, or had used more than five corticosteroid or aminosalicylate enemas in the previous 2 wk | Group 1: Aloe vera gel. [n = 30 (male/female: 16/14)]. 100 mL bid | 5-ASA, prednisolone, azathioprine, topical 5-ASA, topical steroid | 4 wk | (1) Clinical remission (SCCAI ≤2); (2) Sigmoidoscopic remission [Baron score of zero (normal-looking mucosa) or one (mucosal oedema as indicated by loss of the normal vascular pattern)]; (3) Histological remission (Savery-muttu score of ≤ 1, i.e., no loss of colonocytes, absence of crypt inflammation, and normal lamina propria content of mononuclear cells and neutrophils); (4) Clinical improvement (a reduction in SCCAI of ≥ 3 points); (5) Clinical response (remission or improvement); (6) Sigmoidoscopic improvement (decrease in Baron score of ≥ 2 points; and (7) Histological improvement (decrease in Savery-muttu score of ≥ 3 points) |

| Group 2: The same lipqiud product without Aloe vera gel. [n = 14 (male/female: 6/8)] | ||||||||||||

| Ben-Arye et al[22] | Triticum aestivum | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | ND | Double blind; both the true juice and the placebo were packaged in coded, identical, sealed, opaque containers. A driver, blinded to the allocation scheme and given only the addresses for each package, then distributed all the packages | 2 patients in triticum group and 1 in the placebo group | 4 | Age > 18 yr; sigmoidoscopic finding of active UC that involves the left colon; clinical activity comparable with UC; no change in drug treatment (type and dosage) in the month prior to entry; lack of serious systemic involvement–fever > 38 °C, erythema nodosum, arthritis; blood hemoglobin > 11 g%; negative stool culture and test for ova and parasites | ND | Group 1: 100 mL of Triticum aestivum seed juice. [n = 11 (male/female: 6/5)] | - | 1 mo | Improvement (larger than 0.4 in an analog scale where -3 designates the lowest score of aggravation, 0 no change, and +3 highest score of improvement) |

| Group 2: 100 mL of matching placebo. [n = 12 (male/female: 9/3)] |

| Herbal product | IBD type | Study | Patients reported AE | Clinical efficacy | Endoscopic efficacy | Histological efficacy | Recurrence relapse | ||||

| Any AE | Serious AE | Clinical remission | Clinical response | Endoscopic remission | Endoscopic response | Histological remission | Histological response | ||||

| Aloe vera | UC | 16 | H: 6/30 | - | H: 9/ 30 | H: 14/30 | H: 7/26 | H: 12/26 | H: 6/21 | H: 14/21 | - |

| C: 4/14 | C: 1/14 | C: 2/14 | C: 2/11 | C: 3/11 | C: 4/9 | C: 7/9 | |||||

| Andrographis paniculata | UC | 17 | H: 84/149 | H: 4/149 | H: 53/148 | H: 78/148 | H: 65/148 | - | - | - | - |

| C: 45/75 | C: 2/75 | C: 19/75 | C: 30/75 | C: 25/75 | |||||||

| Artemisia absinthium | CD | 18 | - | H: 0/10 | - | H: 8/10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C: 0/10 | C: 2/10 | ||||||||||

| Artemisia absinthium | CD | 19 | - | - | H: 13/20 | H: 18/20 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C: 0/20 | C: 0/20 | ||||||||||

| Boswellia serrata | CD | 20 | H: 29/42 | H: 4/42 | - | - | - | - | - | - | H: 14/42 |

| C: 34/40 | C: 4/40 | C: 14/40 | |||||||||

| Boswellia serrata | Collagenous colitis | 21 | H: 2/16 | H: 0/16 | H: 10/16 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| C: 1/15 | C: 0/15 | C: 4/15 | |||||||||

| Triticum aestivum | UC | 22 | - | - | - | H: 10/11 | - | - | - | - | - |

| C: 5/12 | |||||||||||

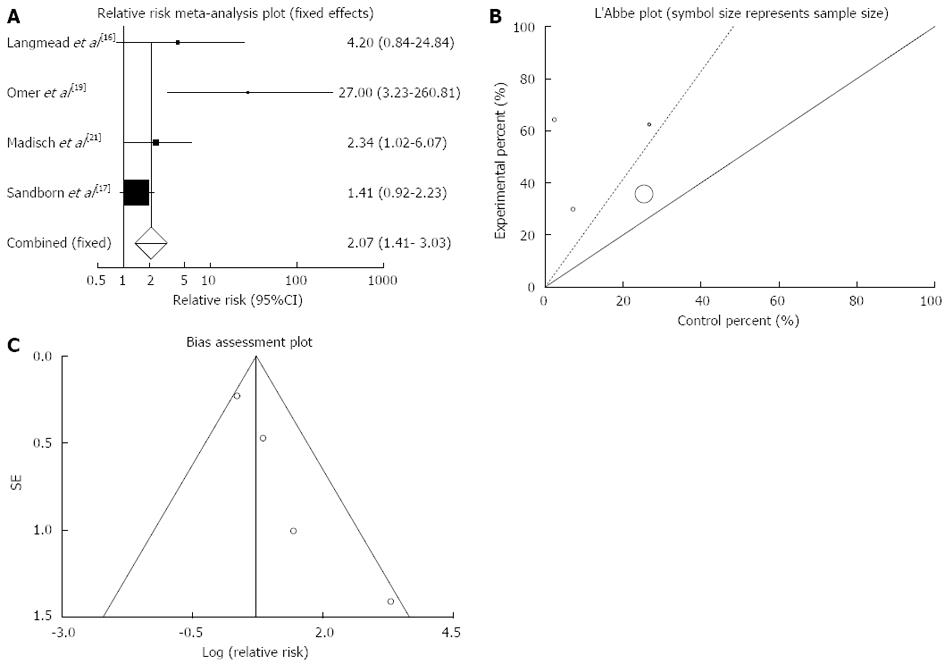

Clinical remission: The summary for RR of clinical remission in IBD patients for four included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16,17,19,21] was 2.07 with 95%CI: 1.41-3.03 (P = 0.0002, Figure 2A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.08, Figure 2B) and could be combined, thus fixed effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical remission in IBD patients among herbal medicines vs placebo therapy was 2.02 (95%CI: 0.37-3.67, P = 0.03 and Kendall’s tau = 1, P = 0.08 (Figure 2C).

The RR of clinical remission in patients with CD[19] was 27 with 95%CI: 3.23-260.81, a significant RR.

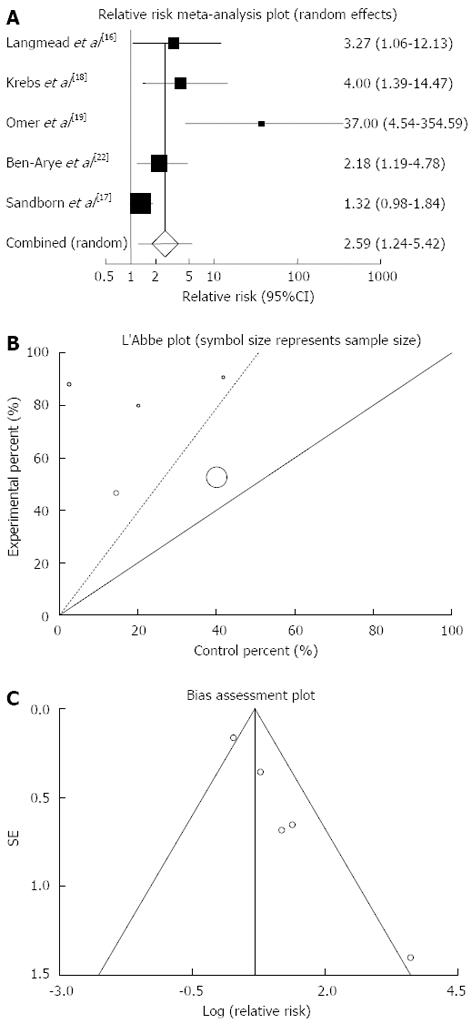

The summary for RR of clinical remission in UC patients for two included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16,17] was 1.59 with 95%CI: 0.8-3.15 (P = 0.18, Figure 3A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.28, Figure 3B) and could be combined but because of few included studies random effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical remission in UC patients could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Based on plant type, RR of clinical remission was significant for Artemisia absinthium (27.00; 95%CI: 3.23-260.81) and Boswellia serrata (2.34; 95%CI: 1.02-6.07) and non-significant for Aloe vera and Andrographis paniculata (Table 3).

| Plant | IBD type | Study | Patients reported AE | Clinical efficacy | Endoscopic efficacy | Histological efficacy | Recurrence relapse | ||||

| Any AE | Serious AE | Clinical remission | Clinical response | Endoscopic remission | Endoscopic response | Histological remission | Histological response | ||||

| Aloe vera | UC | 16 | 0.70 (0.25-2.08) | - | 4.20 (0.84-24.84) | 3.27 (1.06-12.13) | 1.48 (0.44-5.84) | 1.69 (0.69-5.04) | 0.64 (0.25-1.81) | 0.86 (0.55-1.55) | - |

| Andrographis paniculata | UC | 17 | 0.94 (0.75-1.20) | 1.01 (0.22-4.65) | 1.41 (0.92-2.23) | 1.32 (0.98-1.84) | 1.32 (0.93-1.93) | - | - | - | - |

| Artemisia absinthium | CD | 18 | - | 1.00 (0.06-16.69) | - | 9.61 (0.73-126.15), P = 0.09 | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD | 19 | - | - | 27.00 (3.23-260.81) | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Boswellia serrata | CD | 20 | 0.82 (0.66-1.04), P = 0.11 | 0.95 (0.27-3.31), P = 0.94 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.95 (0.52-1.73) |

| Collagenous colitis | 21 | 2.34 (1.02-6.07) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| Triticum aestivum | UC | 22 | - | - | - | 2.18 (1.19-4.78) | - | - | - | - | - |

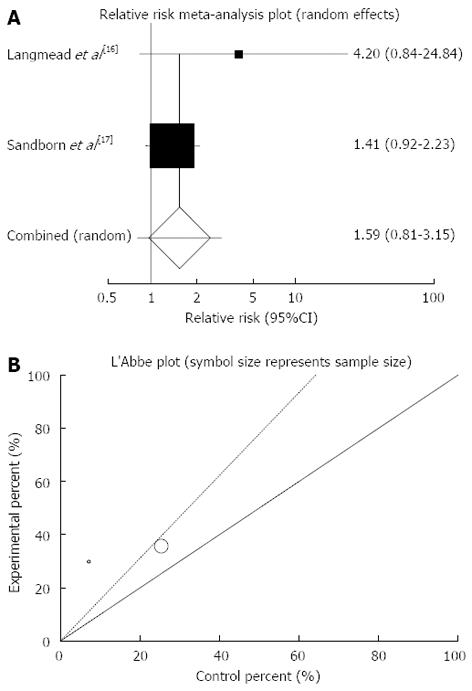

Clinical response: The summary for RR of clinical response in IBD patients for five included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16-19,22] was 2.59 with 95%CI: 1.24-5.42 (P = 0.01, Figure 4A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are heterogeneous (P = 0.08, Figure 4B) and could not be combined, thus the random effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response in IBD patients was 2.33 (95%CI: 1.55-3.11, P = 0.003) and Kendall’s tau = 0.8, P = 0.08 (Figure 4C).

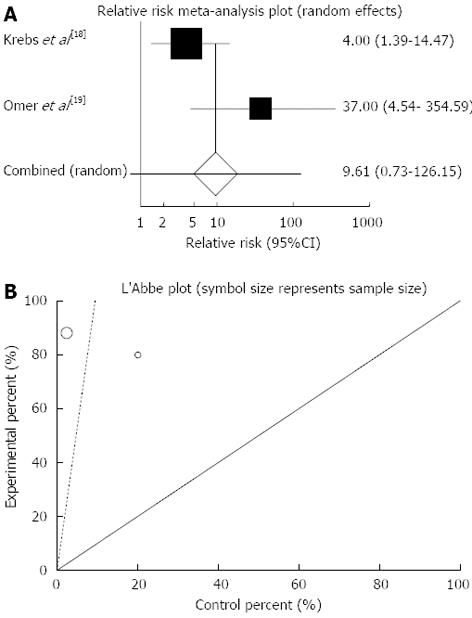

The summary for RR of clinical response in CD patients for two included trials[18,19] was 9.61 with 95%CI: 0.73-126.15 (P = 0.09, Figure 5A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.08, Figure 5B) and could be combined but because of few included studies the random effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response in CD patients could not be calculated because of too few strata.

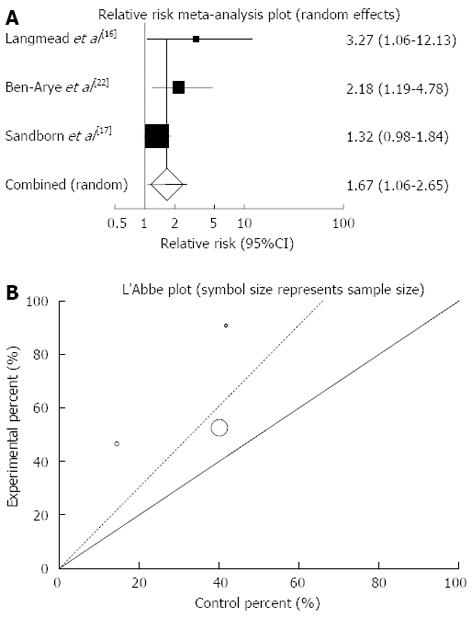

The summary for RR of clinical response in UC patients for three included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16,17,22] was 1.67 with 95%CI: 1.06-2.65 (P = 0.03, Figure 6A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.22, Figure 6B) and could be combined but because of few included studies the random effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for clinical response in UC patients among herbal medicines vs placebo therapy could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Based on plant type, RR of clinical response was significant for Aloe vera (3.27; 95%CI: 1.06-12.13) and Triticum aestivum (2.18; 95%CI: 1.19-4.78) and non-significant for Andrographis paniculata and Artemisia absinthium (Table 3).

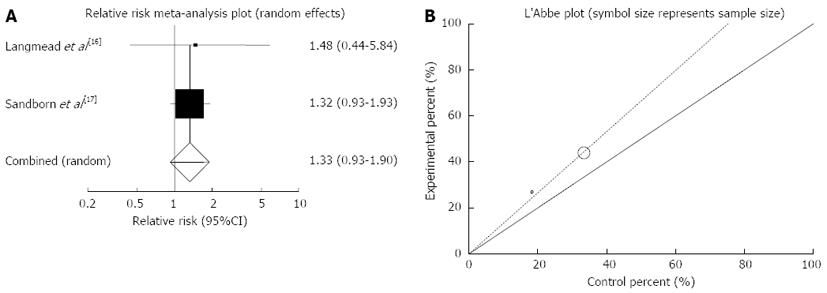

Endoscopic remission: The summary for RR of endoscopic remission in IBD patients for two included trials (all of the patients in these studies had UC) comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16,17] was 1.33 with 95%CI: 0.93-1.9 (P = 0.12, Figure 7A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.87, Figure 7B) and could be combined but because of few included studies random effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for endoscopic remission in IBD (UC) patients could not be calculated because of too few strata.

Based on plant type, RR of endoscopic remission was non-significant for Aloe vera (1.48; 95%CI: 0.44-5.84) and Andrographis paniculata (1.32; 95%CI: 0.93-1.93) (Table 3).

Endoscopic response: The RR of endoscopic response in UC patients comparing herbal medicines with placebo[16] was 1.69 with 95%CI: 0.69-5.04, a non-significant RR.

Histological remission: The RR of histological remission in IBD (UC) patients comparing herbal medicines with placebo[16] was 0.64 with 95%CI: 0.25-1.81, a non-significant RR.

Histological response: The RR of histological response in UC patients comparing herbal medicines with placebo[16] was 0.86 with 95%CI: 0.55-1.55, a non-significant RR.

Relapse: The RR of relapse in CD patients comparing herbal medicines with placebo[20] was 0.95 with 95%CI: 0.52-1.73, a non-significant RR.

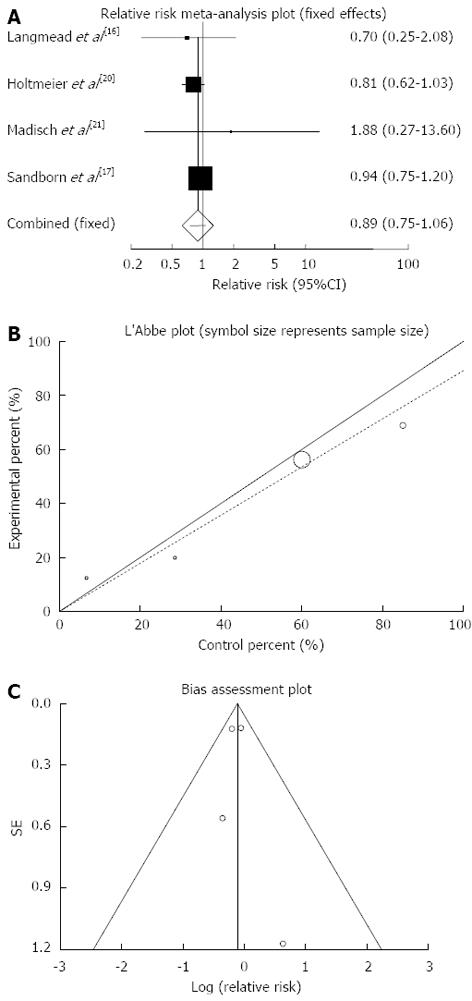

Any adverse events: The summary for relative risk (RR) of any adverse events in IBD patients for four included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[16,17,20,21] was 0.89 with 95%CI: 0.75-1.06 (P = 0.2, Figure 8A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P = 0.71, Figure 8B) and could be combined, thus fixed effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for any adverse events in IBD patients was 0.18 (95%CI: -2.73-3.09, P = 0.81) and Kendall’s tau = 0, P = 0.75 (Figure 8C).

Serious adverse events: The summary for RR of serious adverse events in IBD patients for four included trials comparing herbal medicines to placebo[17,18,20,21] was 0.97 with 95%CI: 0.37-2.56 (P = 0.96, Figure 9A). The Cochrane Q test for heterogeneity indicated that the studies are not heterogeneous (P > 0.99, Figure 9B) and could be combined, thus fixed effects for individual and summary of RR was applied. Regression of normalized effect vs precision for all included studies for serious adverse events in IBD patients was 0.01 (95%CI: -0.19-0.21, P = 0.83) and Kendall’s tau = 0, P = 0.75 (Figure 9C).

In the current meta-analysis, the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines in the management all forms of IBD were compared with placebo. The results showed that herbal medicines may induce clinical remission and clinical response in patients with IBD. Endoscopic efficacy was investigated in two studies, both on patient with UC. Herbal medicines did not demonstrate significant effect on induction of endoscopic remission and endoscopic response. Histopathological efficacy was also evaluated in two studies both on patients with UC and the results were the same as endoscopic efficacy. This may be due to short duration of studies and possible slow action of herbal medicines. Moreover, the scoring system used to assess the mucosal appearance macroscopically is prone to inter-observer variability resulting in non-detecting a significant improvement[23].

The efficacy of herbal medicines in prevention of relapse was investigated in only one study and showed no priority of these products compared to placebo. The number of patients showed any adverse events or serious adverse events were not significantly different between herbal medicines and placebo and this confirmed safety and tolerability of these products.

The present meta-analysis may have been limited by small sample sizes of studies and heterogeneity. Since the included trials involved herbal medicines contained different plants administered to patients with various subtypes of IBD, the trials were disaggregated. Thus, sub-analyses based on type of IBD and plant type was performed. The results of sub-analysis based on IBD type showed that herbal medicines significantly induce clinical remission in patients with CD and clinical response in patients with UC; however the induction of clinical remission in patients with UC and induction of clinical response in patients with CD by herbal medicines were not significant. The results of sub-analyses based on plant type demonstrated that induction of clinical remission was obtained only by Artemisia absinthium and Boswellia serrata and induction of clinical response was gained by only Aloe vera and Triticum Aestivum. None of the plants caused induction of endoscopic or histological efficacy. Boswellia serrata in one study evaluating recurrence rate did not cause prevention of relapse. Induction of adverse events by none of the plants was significant in comparison to that of placebo.

Overall, the results show that herbal medicines may induce clinical efficacy in patients with IBD, but the evidence is too limited to make any confident conclusions. Meta-analysis of clinical trials that have compared efficacy of herbal medicines with that of conventional drugs such as amino-salicylates can be helpful that is being carried out by authors of this paper. Further high quality, large controlled trials using standardized preparation are warranted to better elucidate the effects of these herbs in IBD.

Authors would like to thank help of National Elite Foundation and Iran National Science Foundation.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of gastrointestinal tract. Due to lack of desired efficacy and poor tolerability of conventional drugs, approach toward complementary and alternative medicines especially herbal medicines for the management of IBD are growing. Besides many experimental studies, the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines in IBD have been investigated through several clinical trials.

Although the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines for the management of IBD were evaluated through several clinical trials in comparison to placebo, no meta-analysis has been conducted to reach a convincing conclusion.

Based on this meta-analysis, herbal medicines may safely induce clinical response and remission in patients with IBD without significant effects on endoscopic and histological outcomes, but the number of studies is yet limited to make a strong conclusion.

Regarding desirable effects of herbal medicine in induction of clinical response and remission in IBD and their low adverse events, it would not be surprising to introduce good medicines to clinic if proper standardization and dose adjustments are done.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of herbal medicines in IBD by conducting a meta-analysis. This paper is good for IBD community.

P- Reviewers Gasbarrini A, Maltz C, M’Koma A S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of sulfasalazine in comparison with 5-aminosalicylates in the induction of improvement and maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1157-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | De Cassan C, Fiorino G, Danese S. Second-generation corticosteroids for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: more effective and less side effects? Dig Dis. 2012;30:368-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Do anti-tumor necrosis factors induce response and remission in patients with acute refractory Crohn’s disease? A systematic meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Biomed Pharmacother. 2007;61:75-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nikfar S, Ehteshami-Afshar S, Abdollahi M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and adverse events of infliximab in comparison to corticosteroids and placebo in active ulcerative colitis. Int J Pharmacol. 2011;7:325-332. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of antibiotic therapy for active ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2920-2925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy in patients with active Crohn’s disease. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1983-1988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rahimi F, Elahi B, Derakhshani S, Vafaie M, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy of probiotics for maintenance of remission and prevention of clinical and endoscopic relapse in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2524-2531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rezaie A, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis of the benefit of probiotics in maintaining remission of human ulcerative colitis: evidence for prevention of disease relapse and maintenance of remission. Arch Med Sci. 2008;4:185-190. |

| 9. | Khan KJ, Dubinsky MC, Ford AC, Ullman TA, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:630-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rahimi R, Mozaffari S, Abdollahi M. On the use of herbal medicines in management of inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review of animal and human studies. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:471-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rahimi R, Shams-Ardekani MR, Abdollahi M. A review of the efficacy of traditional Iranian medicine for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4504-4514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Rahimi R, Baghaei A, Baeeri M, Amin G, Shams-Ardekani MR, Khanavi M, Abdollahi M. Promising effect of Magliasa, a traditional Iranian formula, on experimental colitis on the basis of biochemical and cellular findings. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1901-1911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Baghaei A, Esmaily H, Abdolghaffari AH, Baeeri M, Gharibdoost F, Abdollahi M. Efficacy of Setarud (IMod), a novel drug with potent anti-toxic stress potential in rat inflammatory bowel disease and comparison with dexamethasone and infliximab. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2010;47:219-226. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Abdolghaffari AH, Baghaei A, Moayer F, Esmaily H, Baeeri M, Monsef-Esfahani HR, Hajiaghaee R, Abdollahi M. On the benefit of Teucrium in murine colitis through improvement of toxic inflammatory mediators. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2010;29:287-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jadad AR, Enkin MW. Randomised Controlled Trials. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: BMJ Books 2007; . |

| 16. | Langmead L, Feakins RM, Goldthorpe S, Holt H, Tsironi E, De Silva A, Jewell DP, Rampton DS. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral aloe vera gel for active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:739-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sandborn WJ, Targan SR, Byers VS, Rutty DA, Mu H, Zhang X, Tang T. Andrographis paniculata extract (HMPL-004) for active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:90-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Krebs S, Omer TN, Omer B. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha and accelerates healing in patients with Crohn’s disease - A controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2010;17:305-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Omer B, Krebs S, Omer H, Noor TO. Steroid-sparing effect of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) in Crohn’s disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phytomedicine. 2007;14:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Holtmeier W, Zeuzem S, Preiss J, Kruis W, Böhm S, Maaser C, Raedler A, Schmidt C, Schnitker J, Schwarz J. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of Boswellia serrata in maintaining remission of Crohn’s disease: good safety profile but lack of efficacy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:573-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Madisch A, Miehlke S, Eichele O, Mrwa J, Bethke B, Kuhlisch E, Bästlein E, Wilhelms G, Morgner A, Wigginghaus B. Boswellia serrata extract for the treatment of collagenous colitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1445-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ben-Arye E, Goldin E, Wengrower D, Stamper A, Kohn R, Berry E. Wheat grass juice in the treatment of active distal ulcerative colitis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saverymuttu SH, Camilleri M, Rees H, Lavender JP, Hodgson HJ, Chadwick VS. Indium 111-granulocyte scanning in the assessment of disease extent and disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. A comparison with colonoscopy, histology, and fecal indium 111-granulocyte excretion. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:1121-1128. [PubMed] |