Published online Sep 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5586

Revised: June 3, 2013

Accepted: July 18, 2013

Published online: September 7, 2013

Processing time: 133 Days and 21.4 Hours

Gallstone ileus (GI) is characterized by occlusion of the intestinal lumen as a result of one or more gallstones. GI is a rare complication of gallstones that occurs in 1%-4% of all cases of bowel obstruction. The mortality associated with GI ranges between 12% and 27%. Classical findings on plain abdominal radiography include: (1) pneumobilia; (2) intestinal obstruction; (3) an aberrantly located gallstone; and (4) change of location of a previously observed stone. The optimal management of acute GI is controversial and can be: (1) enterotomy with stone extraction alone; (2) enterotomy, stone extraction, cholecystectomy and fistula closure; (3) bowel resection alone; and (4) bowel resection with fistula closure. We describe a case to highlight some of the pertinent issues involved in GI management, and propose a scheme to minimize recurrent disease and postoperative complications. We conclude that GI is a rare condition affecting mainly the older population with a female predominance. The advent of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging has made it easier to diagnose GI. Enterotomy with stone extraction alone remains the most common surgical method because of its low incidence of complications.

Core tip: We present the case of a 56-year-old female who presented at our institution with symptoms of bowel obstruction. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and exploratory laparotomy revealed a large gallstone in the terminal ileus. She underwent enterolithotomy and had an uneventful postoperative course. The literature suggests that gallstone ileus (GI) is a rare condition affecting mainly the older population and has a female predominance. CT and magnetic resonance imaging have made it easier to diagnose GI. Enterotomy with stone extraction alone remains the most common surgical method because of its low incidence of complications.

- Citation: Dai XZ, Li GQ, Zhang F, Wang XH, Zhang CY. Gallstone ileus: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(33): 5586-5589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i33/5586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5586

Gallstone ileus (GI) is characterized by occlusion of the intestinal lumen as a result of one or more gallstones[1,2]. According to reports from the 1990s, GI is a rare complication of gallstones that occurs in 1%-4% of all cases of bowel obstruction and in ≤ 25% of cases of non-strangulated small-bowel obstruction in patients aged > 65 years. The mortality associated with GI ranges between 12% and 27%[3]. GI accounts for only 0.095% of cases of mechanical bowel obstruction in the United States[4]. The optimal management of acute GI is controversial[3,4]. We describe a case here to highlight some of the pertinent issues involved in GI management, and propose a scheme to minimize recurrent disease and postoperative complications.

A 56-year-old female presented with intermittent vomiting and abdominal pain for 7 d. This patient had cholecystolithiasis for 10 years and had been treated with antibiotics. She had been treated in another hospital with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. She had undergone gastrointestinal decompression and regulation of water and electrolytes for approximately 1 wk, but the symptoms had not abated.

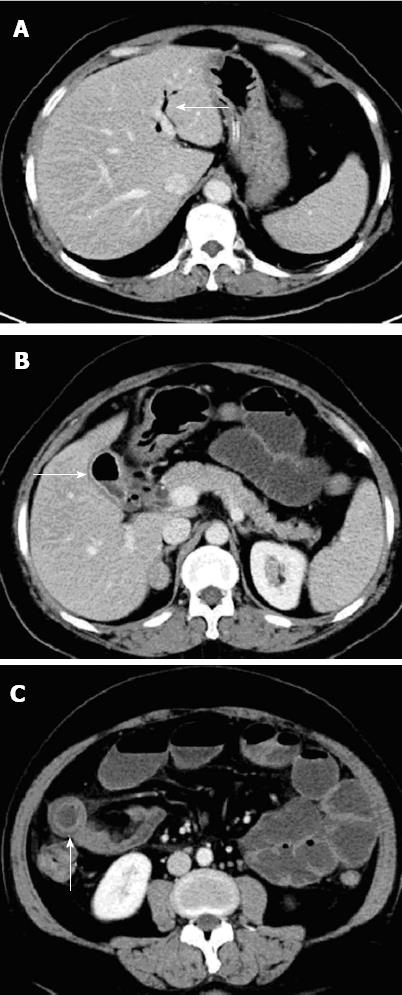

One week after the latest attack, she was referred to our hospital for nausea, vomiting, constipation and abdominal pain. Upon examination, her abdomen was moderately distended, and tympanic and high-pitched bowel sounds were audible. Rectal examination was normal. Blood tests revealed an elevated total leukocyte count (14.4 × 109 cells/L) and unremarkable liver function test values. Plain radiographs of the abdomen were normal (Figure 1). She was treated with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. However, 2 d after hospital admission, clinical deterioration was investigated with computed tomography (CT). CT demonstrated a small-bowel obstruction due to a 50-mm calculus within an ileal loop. CT showed air in the gallbladder and adhesions between the thickened gallbladder wall and duodenal wall. A severe air-fluid level was also seen (Figure 2). We therefore made a diagnosis of GI.

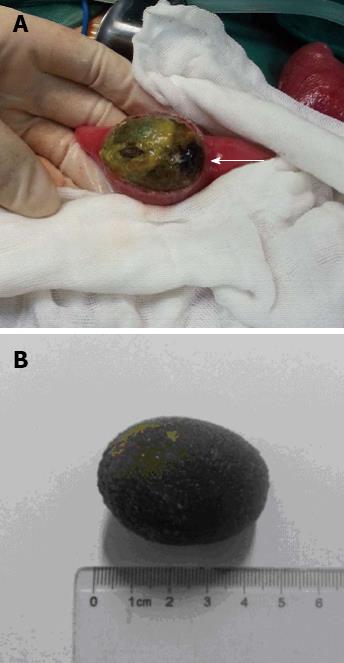

The patient underwent an exploratory laparotomy, during which a wide fistula from the gallbladder to the second part of the duodenum was found. Abdominal adhesions around the gallbladder were very severe. Exploration revealed massively dilated loops of the small bowel proximal to the distal ileum. An obstruction was seen 100 cm from the terminal ileum, where an enterotomy was made to reveal a large gallstone (5 cm × 3 cm × 4 cm). The gallstone was removed and the enterotomy repaired in two layers (Figure 3). The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged home on postoperative day 10.

GI is more common in women, and the ratio of females to males is 3.5 to 1[4]. The gallstone may enter the intestine through a fistula and it can impact anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract[5]. The gallstone must be ≥ 2-2.5 cm in diameter to cause obstruction[6-9]. As shown by Reisner and Cohen, impaction of the stone can occur in any part of the bowel, i.e., the ileum (60.5% of cases), jejunum (16.1%), stomach (14.2%), colon (4.1%), and duodenum (3.5%). It can also be passed spontaneously (1.3%)[3,10]. It occurs most frequently in the terminal ileum and the ileocecal valve because of their narrow lumen and potentially less active peristalsis[10].

If GI occurs in elderly patients with comorbidities, the often vague, intermittent symptoms may delay the diagnosis by days[3]. Presentation is typically non-specific, and often with intermittent symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and pain. We should pay more attention to those patients who have the history of cholecystolithiasis and with symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and pain. In the past, confirming the diagnosis was difficult, but the advent of CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has made it easier to diagnose GI[10,11].

Classical findings on plain abdominal radiography include: (1) pneumobilia; (2) intestinal obstruction; (3) an aberrantly located gallstone; and (4) a change in location of a previously observed stone[9,11-14]. The widespread use of CT with an overall sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of 93%, 100% and 99%, respectively, has aided diagnosis[14]. Interestingly, no aerobilia which can be easily detected by transabdominal ultrasound may be one reason for the delayed diagnosis. Additionally, the absence of significant calcification of the stone reduces the chance of an early diagnosis. In 50% of cases, the diagnosis is often only made at laparotomy[3].

GI is a mechanical intestinal obstruction caused by impaction of gallstones within the lumen of the bowel. Most reports indicate that stones smaller than 2.5 cm usually pass through spontaneously, so conservative treatment (decompression by nasogastric drainage) is conducted before a decision is made to remove the impacted stone by surgical means[6,8].

Management of GI is controversial and includes: (1) enterotomy with stone extraction alone; (2) enterotomy, stone extraction, cholecystectomy and fistula closure; (3) bowel resection alone; and (4) bowel resection with fistula closure[4,6,15].

Enterotomy with stone extraction alone remains the most common surgical method because of its low incidence of complications[4]. Spontaneous closure of the fistulous tract is observed in > 50% of cases[12]. Small-bowel obstruction requires enterolithotomy with a longitudinal incision placed on the anti-mesenteric border proximal to the site of impaction. Careful closure of the enterolithotomy is needed to avoid narrowing of the intestinal lumen, and we usually employ a transverse closure for this reason. The choice of surgical procedure is determined largely by clinical status. GI patients are usually elderly and have comorbidities so enterotomy with stone extraction alone appears to more suitable than more invasive techniques[4,16].

However, 5% of patients who undergo enterolithotomy alone go on to develop biliary symptoms, and 10% require an unplanned reoperation. In the presence of residual stones, the estimated prevalence of recurrence ranged from 5% to 17%, and more than half of these recurrences occur within 6 mo of the index presentation. Retrospective cohort and literature reviews of GI reveal a prevalence of biliary malignancy of 2%-6%[4,17].

We noted that fistula closure, if conducted urgently or as an emergency during the initial procedure, was independently associated with a higher prevalence of mortality than enterotomy and stone extraction alone. The reason may be that elderly patients have multiple comorbidities and an edematous surrounding area. Bowel resection is sometimes necessary, particularly in the presence of a perforation.

Laparoscopy-assisted methods have been reported by Sarli et al[18], who successfully treated three women with GI. Their patients made uneventful recoveries. However, laparoscopy is somewhat more challenging in cases of dilated and an edematous bowel[18,19].

Some special types of GI, such as Bouveret’s syndrome (stones impacting in the duodenum causing gastric outlet obstruction), and stones in the stomach or the colon are suitable for non-surgical therapeutic options in around 20% of the patients. For example laserlithotripsy in Bouveret’s syndrome[20] or extracorporal shock wave lithotripsy[21] or even only endoscopic extraction[22] may be a promising and fast therapeutic alternative.

Historically, wound infections and dehiscence have been cited as being the most common complications after surgery in 25% to 50% of GI cases. In contrast to what has been published so far, the most common postoperative complication is acute renal failure followed by urinary tract infection and wound infections. Gastrointestinal complications related to anastomotic leaks and intra-abdominal abscesses are highest in patients undergoing enterotomy with fistula closure[3,4,12].

If the gallbladder is preserved at the initial procedure, delayed cholecystectomy must be addressed. This is because 5% of patients who have undergone enterolithotomy alone go on to develop biliary symptoms, and the risk of patent fistula reflux and resulting biliary malignancy[3,4,12]. In conclusion, GI is a rare condition affecting mainly the older population with a female predominance. If GI occurs in elderly patients with comorbidities, the often vague, intermittent symptoms may delay the diagnosis by days. The advent of CT and MRI has made it easier to diagnose GI. Enterotomy with stone extraction alone remains the most common surgical method because of its low incidence of complications.

P- Reviewer Maiss J S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Chatterjee S, Chaudhuri T, Ghosh G, Ganguly A. Gallstone ileus-an atypical presentation and unusual location. Int J Surg. 2008;6:e55-e56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chou JW, Hsu CH, Liao KF, Lai HC, Cheng KS, Peng CY, Yang MD, Chen YF. Gallstone ileus: report of two cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1295-1298. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441-446. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Halabi WJ, Kang CY, Ketana N, Lafaro KJ, Nguyen VQ, Stamos MJ, Imagawa DK, Demirjian AN. Surgery for Gallstone Ileus: A Nationwide Comparison of Trends and Outcomes. Ann Surg. 2013;Jan 4; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hussain Z, Ahmed MS, Alexander DJ, Miller GV, Chintapatla S. Recurrent recurrent gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:W4-W6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kasahara Y, Umemura H, Shiraha S, Kuyama T, Sakata K, Kubota H. Gallstone ileus. Review of 112 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg. 1980;140:437-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Syme RG. Management of gallstone ileus. Can J Surg. 1989;32:61-64. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Ihara E, Ochiai T, Yamamoto K, Kabemura T, Harada N. A case of gallstone ileus with a spontaneous evacuation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1259-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Al-Obaid O. Gallstone ileus: a forgotten rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:39-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gupta M, Goyal S, Singal R, Goyal R, Goyal SL, Mittal A. Gallstone ileus and jejunal perforation along with gangrenous bowel in a young patient: A case report. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2:442-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ripollés T, Miguel-Dasit A, Errando J, Morote V, Gómez-Abril SA, Richart J. Gallstone ileus: increased diagnostic sensitivity by combining plain film and ultrasound. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Clavien PA, Richon J, Burgan S, Rohner A. Gallstone ileus. Br J Surg. 1990;77:737-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lassandro F, Gagliardi N, Scuderi M, Pinto A, Gatta G, Mazzeo R. Gallstone ileus analysis of radiological findings in 27 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu CY, Lin CC, Shyu RY, Hsieh CB, Wu HS, Tyan YS, Hwang JI, Liou CH, Chang WC, Chen CY. Value of CT in the diagnosis and management of gallstone ileus. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2142-2147. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Ravikumar R, Williams JG. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:279-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Doko M, Zovak M, Kopljar M, Glavan E, Ljubicic N, Hochstädter H. Comparison of surgical treatments of gallstone ileus: preliminary report. World J Surg. 2003;27:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hayes N, Saha S. Recurrent gallstone ileus. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sarli L, Pietra N, Costi R, Gobbi S. Gallstone ileus: laparoscopic-assisted enterolithotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:370-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Okubo H, Nogawa T, Jibiki M. [A case of gallstone ileus which the cholecystoduodenal fistula closed spontaneously after laparoscopic-assisted simple enterolithotomy]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2006;103:1157-1162. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Maiss J, Hochberger J, Hahn EG, Lederer R, Schneider HT, Muehldorfer S. Successful laserlithotripsy in Bouveret’s syndrome using a new frequency doubled doublepulse Nd: YAG laser (FREDDY). Scan J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:791-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sackmann M, Holl J, Haerlin M, Sauerbruch T, Hoermann R, Heinkelein J, Paumgartner G. Gallstone ileus successfully treated by shock-wave lithotripsy. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1794-1795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bedogni G, Contini S, Meinero M, Pedrazzoli C, Piccinini GC. Pyloroduodenal obstruction due to a biliary stone (Bouveret’s syndrome) managed by endoscopic extraction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:36-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |