Published online Sep 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5581

Revised: July 10, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: September 7, 2013

Processing time: 108 Days and 20.5 Hours

This study explored the clinical value of endoscopic ligation for the treatment of upper gastrointestinal (GI) protuberant lesions in children. According to the appearance and size of lesions, we used different ligation techniques for the treatment of the lesions. Endoscopic ultrasonography was used for preliminary characterization of the lesions. One case diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome was successfully treated by a detachable snare. Two cases with semi-pedunculated or broad-base lesions originating from the submucosal layer of the upper GI were treated with endoscopic variceal ligation; endoscopic examination showed that one case had complete healing 11 wk after ligation, while an ulcer scar was observed at the ligation site after 6 wk in the other case. All lesions were successfully ligated at the first attempt. No significant complications occurred either during or after the procedure. Selective endoscopic ligation of upper GI lesions is an effective and safe treatment for upper GI protuberant lesions in children.

Core tip: Endoscopic ligation is an effective method in the management of protuberant lesions. It is less invasive and less expensive than surgical interventions. However, there are few studies of this technique in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal (GI) lesions in children. This paper reports selective endoscopic ligation for the treatment of different upper GI protuberant lesions in children. Endoscopic ultrasonography was used to determine the depth of invasion and provided a preliminary characterization of the lesions.

- Citation: Wang L, Chen SY, Huang Y, Wu J, Leung YK. Selective endoscopic ligation for treatment of upper gastrointestinal protuberant lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(33): 5581-5585

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i33/5581.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5581

Protuberant lesions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract may cause clinical symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, bleeding, intussusception, obstruction) and have malignant potential. In addition, the presence of the lesion is a source of psychological distress. With the development of endoscopic techniques and devices, endoscopic treatment has become an effective method for protuberant lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. It is less invasive than surgical interventions.

Endoscopic ligation has been widely used in the management of post polypectomy bleeding, bleeding of esophageal and gastric varices, and angiodysplasias[1]. In 2004, Sun et al[2] first reported endoscopic band ligation without electrosurgery was an effective and safe treatment for resection of small upper GI leiomyoma. They found most leiomyomas could slough spontaneously within 3.6 to 4.5 wk. Complications related to use of electrosurgery were avoided. There was a case report about colonoscopic polypectomy with a detachable snare to remove a large juvenile polyp in 1-year-old girl[3]. However, there are few published reports regarding endoscopic ligation to treat upper GI protuberant lesions in children. Here, we report three patients with upper GI protuberant lesions who received endoscopic treatment with ligation.

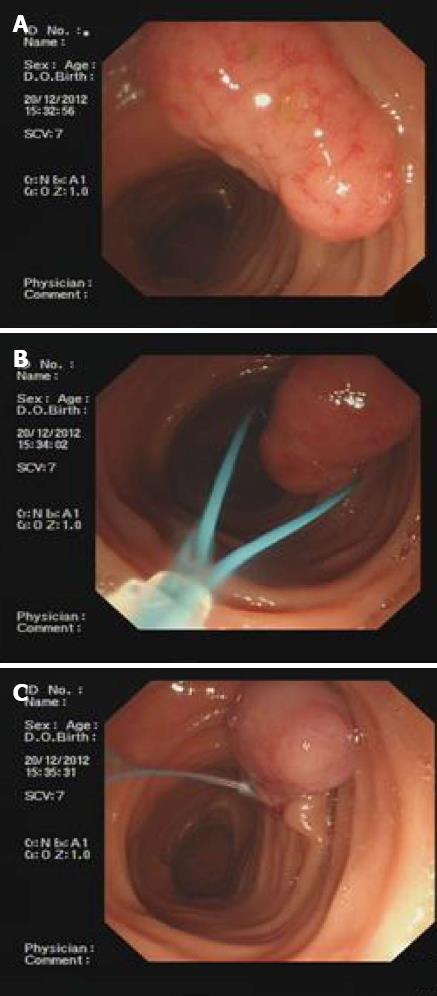

A 4-year-old girl presented with abdominal pain for 6 mo. She was diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Under general anesthesia, conventional upper GI endoscopic examination (GIF-XQ260, Olympus, Japan) revealed multiple polyps. A large, 25 mm × 15 mm, pedunculated polyp with a hyperemic and edematous surface was found in the descending part of the duodenum (Figure 1). Another polyp with a thick stalk, 16 mm × 10 mm in size, also appeared in the opposite side of the duodenal papilla. To remove the two large polyps safely, we performed endoscopic ligation with detachable snares (MAJ339, Olympus, Japan). The device was composed of an elliptically shaped nylon loop and a silicone-rubber stopper which maintained the tightness of the loop. The nylon loop was placed at the base of the stalk, tightened around the stalk, then the stopper was detached from the device. We observed the color change in the target lesion to ensure proper tightening, when the ligated lesion changed to dark red because of congestion. A smaller lesion, 3 mm × 3 mm, was found in the gastric body. It was removed using the electrocoagulation technique. No complications occurred during or after the procedure using the detachable snare.

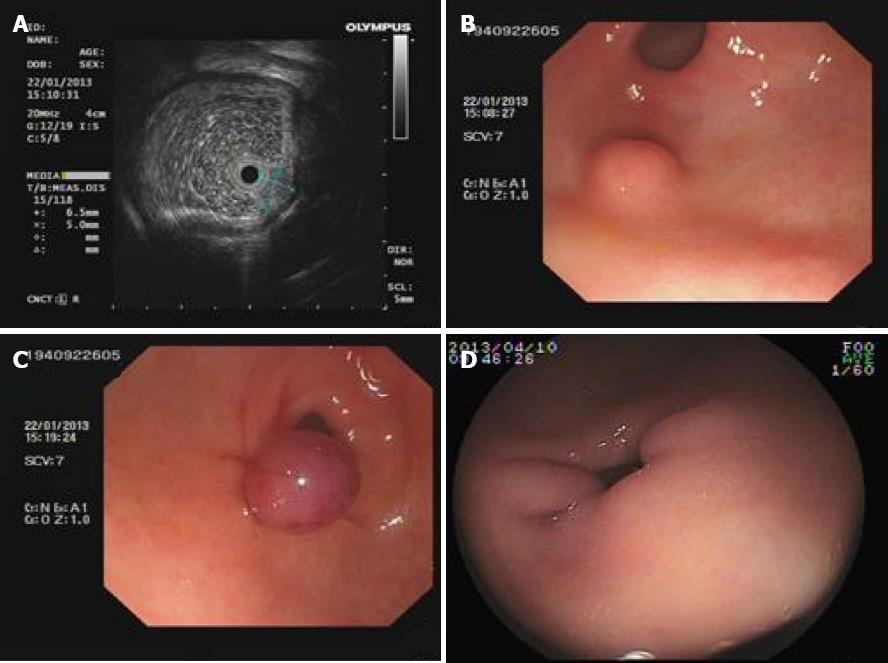

A 10-year-old boy with nausea and belching for 2 mo underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIF-XQ260, Olympus, Japan) in our hospital. The result revealed a protuberant lesion located in the gastric antrum. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was performed using a radial echoendoscope with a 20 MHz catheter probe (UM-DP12-25R, Olympus, Japan), and showed a 6.5 mm × 5.0 mm hypoechoic, homogeneous lesion originating from the submucosal layer. The lesion did not involve the muscularis propria. Endoscopic ligation was performed using an attached endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) device (Six Shooter Saeed Multiband Ligator, Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, United States), which aspirated the lesion into the ligator cap, and then an elastic rubber band was released then tightened around the base of the lesion (Figure 2). The goal of ligation was to create a polypoid form with a pseudo stalk. For complete ligation, suction should be maintained for at least 1 min before releasing the rubber band. There were no significant procedure-related complications. The lesion completely healed within 11 wk after the ligation.

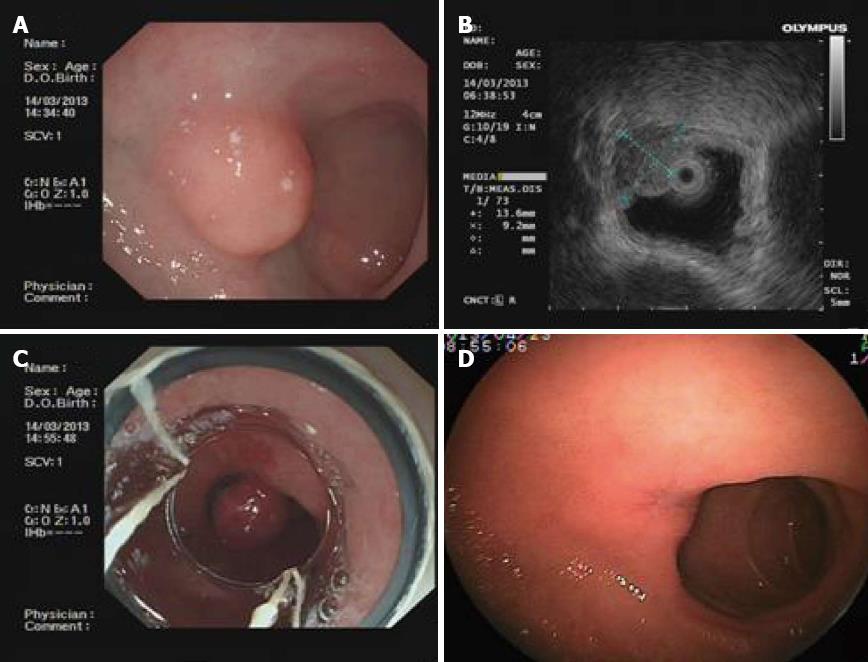

A 10-year-old boy with an episode of recurrent abdominal pain was referred to our hospital for gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIF-XQ260, Olympus, Japan). Under general anesthesia, EUS examination showed a hypoechoic homogeneous mass, 13.6 mm × 9.2 mm in size, originating from the submucosal layer of the duodenal bulb (Figure 3). It did not extend to the muscularis propria. The ligation of this lesion was carried out with the EVL device. The lesion was sucked sufficiently into the ligator cap and the band was tightened to ligate the base of the tissue. No complications were reported during the procedure. Four days later, GI endoscopy showed sloughing of the raised lesion, and an ulcer could be observed. A scar was seen at the ligation site on a follow-up examination of 6 wk later.

There has been remarkable progress in the use of endoscopic treatment for gastrointestinal diseases. A detachable snare for endoscopic use was first developed by Hachisu[4]. Large polyps or other raised lesions have been successfully removed by detachable snares. In a randomized trial, Iishi et al[5] used endoscopic ligation with a detachable snare for the stalk of a large pedunculated polyp and evaluated the safety and effectiveness of the procedure in comparison with conventional endoscopic snare polypectomy. Results showed that no bleeding occurred in 47 patients assigned to colonoscopic polypectomy with a detachable snare, but bleeding occurred in five of 42 patients who received conventional colonoscopic polypectomy. Moreover, the use of a detachable snare reduced the duration of hospitalization after polypectomy. In 2005, Raju et al[6] first described a new technique for successful removal of a large pedunculated, 4 cm wide, broad-based colonic lipoma using endoloops without the need for cautery. Lee et al[7] reported that nine cases diagnosed with large pedunculated GI submucosal tumors were successfully treated by endoloop ligation in 2008, and the tumors were removed within 4 wk. Recently, a trial was published to evaluate the clinical impact of selective ligation using a detachable snare for small intestinal polyps in three adult patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome[8]. The technique of endoscopic ligation is safer than conventional snare polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal resection. It could reduce the risk of bleeding and injury of the deeper tissue layers. However, to our knowledge, the effect of endoscopic ligation for upper GI protuberant lesions in children has not been reported.

According to our experience, there are two aspects to be considered in endoscopic treatment. One is the appearance of elevated lesions. A study described some instances where the use of a detachable snare was ineffective for colonoscopic polypectomy of large polyps with thin stalks or for lesions that were semi-pedunculated[9]. It is difficult to tighten the lesion sufficiently in semi-pedunculated or broad-based lesions, as the loop is more likely to slip off. A target lesion positioned at the 5 o’clock to 7 o’clock position is easier to remove by an endoloop[1]. Huang et al[10] reported the methodology for different lesions using an EVL device or endoloop. Small GI stromal tumors (≤ 12 mm) were treated by endoscopic band ligation with an EVL device. Large pedunculated tumors (> 12 mm) could be managed by endoscopic ligation with a detachable endoloop, while ligation of large sessile tumors was carried out with a large-sized transparent cap plus an endoloop. In our cases, we used a detachable snare for large pedunculated lesions. If the lesion was semi-pedunculated or sessile, endoscopic ligation was carried out with an attached band ligator device. In one of the two cases using an EVL device, the lesion was larger than 12 mm in diameter. For smaller lesions (3 mm × 3 mm), conventional electrocoagulation was performed. Thus, selective ligation is essential to avoid complications.

The second consideration is that endoscopic band ligation is associated with a risk of perforation. It is necessary to be careful to avoid aspirating excessive tissue into the cap. Perforations were reported in two studies after endoscopic band ligation[11,12]; two cases were GI stromal tumors in the gastric fundus, and one was a gastric submucosal tumor partly connecting with the muscularis propria. The reason might be that all the layers of the gastric wall were ligated. It seems that the risk of perforation is greater with deeper layer tumors. Determination of the origin of the lesion and appropriate suction force are essential factors that should be considered.

Endoscopic ligation allows the lesion to slough spontaneously. The main limitation of this technique is the difficulty in retrieving the tissue specimen. Histopathologic diagnoses could not be made. However, protuberant lesions in children are mostly considered as benign and to have very low potential for malignant transformation. Sun et al[13,14] reported that EUS-assisted band ligation with systematic follow-up by EUS was an effective treatment for small upper GI stromal tumors. EUS was used to determine the histologic layer of origin and evaluate whether the mass was confined completely by the band. It has significant value in the diagnosis of submucosal lesions. In the present study, EUS examination was used to identify the depth of invasion. It provided preliminary identification of the property of the lesion. We recommend that our patients should have close follow-up in order to detect any recurrence early.

In conclusion, endoscopic ligation appears to be a feasible method for removal of upper GI lesions in children. According to the characteristics and volume of the lesions, selecting the correct application of ligation and controlling the suction force can reduce the risk of related complications, such as hemorrhage and perforation. In addition, combining endoscopic ligation with EUS examination may be a useful technique for submucosal tumors in children. Pediatric experience with this endoscopic technique remains limited. Thus, studies involving more subjects and longer follow-up are needed to further define the clinical role of endoscopic ligation in children.

P- Reviewer Ozkan OV S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Rengen MR, Adler DG. Detachable Snares (Endoloop). Techniques in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2006;8:12-15. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun S, Jin Y, Chang G, Wang C, Li X, Wang Z. Endoscopic band ligation without electrosurgery: a new technique for excision of small upper-GI leiomyoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:218-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Okazaki K, Takakuwa H, Nishio A. A large juvenile polyp in a 1-year-old child safely removed by colonoscopic polypectomy with a detachable snare. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:118-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hachisu T. A new detachable snare for hemostasis in the removal of large polyps or other elevated lesions. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:70-74. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Narahara H, Iseki K, Sakai N. Endoscopic resection of large pedunculated colorectal polyps using a detachable snare. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:594-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Raju GS, Gomez G. Endoloop ligation of a large colonic lipoma: a novel technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:988-990. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lee SH, Park JH, Park do H, Chung IK, Kim HS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Cho HD. Endoloop ligation of large pedunculated submucosal tumors (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:556-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takakura K, Kato T, Arihiro S, Miyazaki T, Arai Y, Nakao Y, Komoike N, Itagaki M, Odagi I, Hirohama K. Selective ligation using a detachable snare for small-intestinal polyps in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E264-E265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, Kusumi F, Maruo T, Ohana M, Tominaga M, Okano A, Yunoki Y. Ineffective use of a detachable snare for colonoscopic polypectomy of large polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:496-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang WH, Feng CL, Lai HC, Yu CJ, Chou JW, Peng CY, Yang MD, Chiang IP. Endoscopic ligation and resection for the treatment of small EUS-suspected gastric GI stromal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1076-1081. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Siyu S, Sheng W, Guoxin W, Nan G, Jingang L. Gastric perforations after ligation of GI stromal tumors in the gastric fundus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:615-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xing XB, Wang JH, Chen MH, Cui Y. Perforation posterior to endoscopic band ligation of a gastric submucosal tumor. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E296-E297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sun S, Ge N, Wang C, Wang M, Lü Q. Endoscopic band ligation of small gastric stromal tumors and follow-up by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:574-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun S, Ge N, Wang S, Liu X, Lü Q. EUS-assisted band ligation of small duodenal stromal tumors and follow-up by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:492-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |