Published online Sep 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5528

Revised: June 6, 2013

Accepted: July 4, 2013

Published online: September 7, 2013

Processing time: 193 Days and 16.3 Hours

AIM: To summarize our experience in the application of Crurasoft® for antireflux surgery and hiatal hernia (HH) repair and to introduce the work of Chinese doctors on this topic.

METHODS: Twenty-one patients underwent HH repair with Crurasoft® reinforcement. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and HH-related symptoms including heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, dysphagia, and abdominal pain were evaluated preoperatively and 6 mo postoperatively. A patient survey was conducted by phone by one of the authors. Patients were asked about “recurrent reflux or heartburn” and “dysphagia”. An internet-based Chinese literature search in this field was also performed. Data extracted from each study included: number of patients treated, hernia size, hiatorrhaphy, antireflux surgery, follow-up period, recurrence rate, and complications (especially dysphagia).

RESULTS: There were 8 type I, 10 type II and 3 type III HHs in this group. Mean operative time was 119.29 min (range 80-175 min). Intraoperatively, length and width of the hiatal orifice were measured, (4.33 ± 0.84 and 2.85 ± 0.85 cm, respectively). Thirteen and eight Nissen and Toupet fundoplications were performed, respectively. The intraoperative complication rate was 9.52%. Despite dysphagia, GERD-related symptoms improved significantly compared with those before surgery. The recurrence rate was 0% during the 6-mo follow-up period, and long-term follow-up disclosed a recurrence rate of 4.76% with a mean period of 16.28 mo. Eight patients developed new-onset dysphagia. The Chinese literature review identified 12 papers with 213 patients. The overall recurrence rate was 1.88%. There was no esophageal erosion and the rate of dysphagia ranged from 0% to 24%.

CONCLUSION: The use of Crurasoft® mesh for HH repair results in satisfactory symptom control with a low recurrence rate. Postoperative dysphagia continues to be an issue, and requires more research to reduce its incidence.

Core tip: With a focus on the mesh fixation technique, the application of Crurasoft® for antireflux surgery and hiatal hernia repair achieved satisfactory outcome. The recurrence rate was 0% during the 6-mo follow-up period, and long-term follow-up disclosed a recurrence rate of 4.76% with a mean period of 16.28 mo. Eight patients developed new-onset dysphagia and this gradually resolved without difficulty in swallowing solid food in 6 patients. The Chinese literature review identified 12 papers with 213 patients. The overall recurrence rate was 1.88%. There was no esophageal erosion and the rate of dysphagia ranged from 0% to 24%.

- Citation: Zhang W, Tang W, Shan CX, Liu S, Jiang ZG, Jiang DZ, Zheng XM, Qiu M. Dual-sided composite mesh repair of hiatal hernia: Our experience and a review of the Chinese literature. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(33): 5528-5533

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i33/5528.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5528

Laparoscopic fundoplication is a safe and effective alternative to long-term medical treatment for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and hiatal hernia (HH)[1]. Cryoplasty is considered to be an essential part of antireflux surgery[2]. Possible reasons for failed laparoscopic antireflux surgery and disruption of HH repair are lateral tension following simple hiatal closure, or poor character of the crural musculature. The use of a mesh, either by reducing tension or reinforcing the crural musculature, is associated with a significantly lower recurrence rate[1-5].

Despite this, most concerns are focused on mesh-related complications (including intraluminal erosion, fibrosis, and esophageal stenosis)[3,6]. Although few mesh-related complications at the hiatus have been reported, anecdotal observations suggest that this complication may be more common[7]. Moreover, surgery to manage these complications is complex and may require esophagectomy or gastrectomy[3]. For these reasons, many surgeons avoid the use of synthetic mesh in HH repair[8].

The ideal mesh generates adhesion to the diaphragmatic surface and not the visceral side[4]. “V” shaped composite polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) prostheses (dual-sided composite mesh, Crurasoft®) have some of these features. PTFE encourages ingrowth of host tissue from the underlying crura, producing local fibrosis and a more uniform mesh-tissue complex. ePTFE was thought to have a benign behavior as opposed to hollow viscera[9], with encapsulation of the material and neomesothelialization of the exposed abdominal surface, thus becoming isolated from the esophagus and stomach[3]. That is, dual-sided mesh has the merits of prosthetic mesh and may avoid possible major complications. Chilintseva et al[10] reported the preliminary results of the use of this dual-sided prosthesis for large HH repairs, demonstrating satisfactory results. Although there was no erosion of the esophagus or stomach, severe periprosthetic fibrosis resulted in postoperative dysphagia in two patients, requiring reoperation. The authors proposed that positioning the mesh with care should be emphasized[10].

To reduce postoperative dysphagia, some propose that space should be allowed between the esophagus and the mesh[11]. We summarize our experience in the application of Crurasoft® for antireflux surgery and HH repair, focusing on whether a reduction in postoperative complications, especially erosion and dysphagia, can be achieved if technical attention to mesh fixation is applied. Moreover, Crurasoft® is the most commonly used prosthetic mesh in China. We also analyzed and introduced the work of Chinese doctors on this topic, as the Chinese language is still an obstacle for academic communication.

From May 2010 to July 2012, 48 patients underwent surgery for pH-proven symptomatic GERD with HH in our institution. Of these, 21 patients (14 male, 7 female) underwent hiatal repair with an onlay Crurasoft® mesh reinforcement and were enrolled in this retrospective analysis. The indication for mesh implantation included a HH length longer than 3 cm, obesity, and weak hiatus tissue.

GERD and HH related symptoms including heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, dysphagia, and abdominal pain were evaluated preoperatively and 6 mo postoperatively. The severity of symptoms was evaluated using a scaled 0-10 visual analog score, as previously described in the literature[12].

Preoperative barium contrast swallowing or a computed tomography scan was used to evaluate the type and size of the HH. The presence and severity of esophagitis was confirmed by upper endoscopy. pH monitoring (24-h) and esophageal manometry were performed in all patients to evaluate lower esophageal sphincter function and esophageal motility.

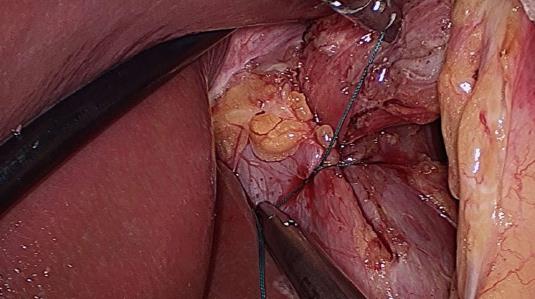

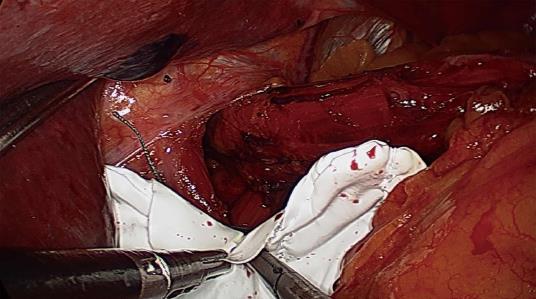

Five trocars were used during laparoscopic surgery. The stomach was first reduced into the abdomen, followed by mobilization of the distal esophagus with at least 3 cm of intraabdominal esophagus restored to the abdominal cavity. All patients underwent primary closure of the hiatus with between 2 and 5 nonabsorbable sutures for posterior Cryoplasty, depending on the size of the hiatus defect (Figure 1). Additional anterior Cryoplasty was also performed if the defect was wide. A V-shaped dual-sided composite mesh (Crurasoft®, Composix mesh, CR Bard, Cranston, United States) was used to reinforce the primary repair, with the PTFE side facing the diaphragm (Figure 2). The lower of the two arms was positioned about 2-3 mm below the first stitch, and fixed with staples (EMS, Johnson and Johnson). Additional staples were applied to secure the mesh to the right and left crura and flatten it. The small ePTFE “tongue” was placed to protect the posterior esophageal wall from contacting the PTFE margin. After closing the hiatus, a fundoplication (Nissen/Toupet) was performed.

Operative duration and size of HH (length and width), were recorded.

In January 2013, a patient survey was conducted by phone by one of the authors. Patients were asked about “recurrent reflux or heartburn” and “dysphagia.” Dysphagia was defined as new-onset difficulty in swallowing; severity (mild/severe) and duration of symptoms (temporary/permanent, duration shorter than 6 mo was defined as temporary) were also surveyed. Patients were also asked about “whether you are satisfied with the outcome of surgery”.

An internet-based Chinese literature search was performed using the Chinese Medical Literature database (Chongqing VIP) between January 2000 and December 2012. The key words “hiatal hernia”, “GERD”, and “mesh” were used in all possible combinations to identify relevant articles. If data appeared appropriate for analysis, the abstract and full article were retrieved for in-depth review. All reference lists in the papers were manually searched for relevant articles. Inclusion criteria were: (1) antireflux surgery with HH repair using Crurasoft® composite mesh; (2) reports described surgical technique details; and (3) reports documented outcome of recurrence and follow-up data. The literature search, study selection, and data extraction were performed by two independent authors. Data extracted from each study included: number of patients treated, hernia size, hiatorrhaphy, antireflux surgery, follow-up period, recurrence rate, and complications (especially dysphagia).

All patients were informed about the study protocol. Written consent for the investigation in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Changzheng Hospital was obtained.

The student’s t test and Pearson χ2 test were used to compare means and categorical variables, respectively. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Classification of HH is listed in Table 1. There were 8 type I, 10 typeII, and 3 type III HHs in this group. Mean operative time was 119.29 min (range 80-175 min). Intraoperatively, both the length and width of the hiatal orifice were measured, (4.33 ± 0.84 and 2.85 ± 0.85 cm, respectively; Table 2). Thirteen and 8 Nissen and Toupet fundoplications were performed, respectively.

| Type | Description |

| I | Sliding hernia with the GEJ above the diaphragm |

| II | Paraesophageal hiatus hernia. A part of the stomach herniates through the hiatus and lies beside the esophagus, without movement of the GEJ |

| III | Combined hernia. The combination of type I and II |

| IV | A large defect in the hiatus, allowing other organs to enter the hernia sac |

| Item | Value |

| Age (yr) | 53.81 ± 13.76 (21-75) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.95 ± 3.11 (21-35) |

| Hiatal hernia length (cm) | 4.33 ± 0.84 (3.1-6.3) |

| Hiatal hernia width (cm) | 2.85 ± 0.85 (1.8-5.4) |

| DeMeester score | 50.30 ± 27.73 (12.7-112.7) |

| Surgery duration (min) | 119.29 ± 23.84 (80-175) |

| Postoperative stay (d) | 4.71 ± 0.85 (4-7) |

There was no mortality and no conversion to open surgery. The intraoperative complication rate was 9.52% (one spleen capsular laceration and 1 pneumothorax, all repaired laparoscopically without sequelae). Eight patients complained of new-onset dysphagia with difficulty eating solid food. No early reoperation or intervention (e.g., endoscopic dilatation) was required. The median length of postoperative hospital stay was 5 (range 4-7) d.

Preoperative and postoperative symptoms of GERD and HH were compared. As listed in Table 3, all relevant symptoms (except for dysphagia) improved significantly. 10 patients agreed to have a barium meal; no recurrence was demonstrated.

| Before surgery | After surgery | P value | |

| Heartburn | 5.33 ± 1.65 | 2.14 ± 1.74 | 0 |

| Regurgitation | 5.00 ± 1.64 | 1.95 ± 1.16 | 0 |

| Chest pain | 3.62 ± 1.99 | 1.29 ± 1.15 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 2.57 ± 1.66 | 1.62 ± 1.86 | 0.087 |

| Abdominal pain | 2.33 ± 1.28 | 1.38 ± 1.12 | 0.014 |

One patient was lost to follow-up. The mean follow-up period was 16.28 (6-32) mo. The overall satisfaction rate was 85.71% (18/21). One patient had a recurrence confirmed at the 8 mo postoperative visit, with the major complaint being dysphagia, different from her preoperative symptoms of heartburn. Barium meal examination showed a type II paraesophageal hernia. In a review of her history, she developed dysphagia at postoperative month 3, following an episode of severe vomiting. This patient scored the outcome of surgery as dissatisfactory and was reluctant to undergo reoperation. The other two patients presented with recurrence of heartburn or regurgitation 4 and 7 mo following surgery, respectively. In these cases, barium swallowing failed to detect HH recurrence. Both patients underwent Nissen fundoplication without symptoms of dysphagia.

Of the 8 patients who complained of postoperative dysphagia, this gradually resolved without difficulty in swallowing solid food in 6 patients. The average period to resolution of dysphagia was 5.2 (range 4-7) mo. The remaining 2 patients complained of mild to moderate dysphagia, unabated even at the final phone call contact (11 and 19 mo postoperatively, respectively). One patient was confirmed to have a slight stricture at the level of the hiatus, for which dilatation achieved slight resolution. The other patient refused further workup and intervention.

Our literature search identified 24 articles for review. Twelve papers fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with a total of 213 patients included in the final analysis. Reasons for exclusion were: no follow-up data (n = 8), pediatric surgery (n = 1), review (n = 1), and overlapping study populations (n = 2) (Table 4)[13-24]. All surgery involved hiatoplasty and fundoplication other than gastropexy. There were only 3 randomized controlled trials. Fei et al[24] concluded that reinforcement of HH repair with Crurasoft® significantly improved HH-related symptoms. Zou et al[21] confirmed that the use of Crurasoft® significantly reduced recurrence from 36.4% with simple closure to 10%, with a follow-up period greater than 1 year. Yao et al[22] reported that there was 1 hernia recurrence following mesh placement in the 1-year follow-up period, compared with 3 cases in the simple Cryoplasty group. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.300). Recurrence rates varied from 0% to 25%. This disparity might be due to differences in the definition of recurrence. Some authors define recurrence as symptoms, without radiological confirmation. The highest anatomic recurrence was reported by Zou et al[21] (10%), where all the HH in that cohort were larger than 6 cm. The overall anatomic recurrence rate was 1.88% (4/213). There were no cases of esophageal or stomach erosion. Postoperative dysphagia varied from 0% to 24% (median 6.67%).

| Author | Patients | Hernia size | Hiatorrhaphy | Antireflux surgery | Follow-up (mo) | Recurrence rate | Complications |

| Chu et al[13] | 12 | III (8), IV (4) | Yes | Nissen | 12-60 | 0/12 | - |

| Wang et al[14] | 15 | I (6), II (7), III (2) | Yes | Toupet | Median 18 | 0/15 | 1 dysphagia, 2 PPI treatment |

| Tai et al[15] | 21 | I (9), II (4), III (6), IV (2) | Yes | Toupet | 1-16 | 0/21 | 3 dysphagia |

| Ji et al[16] | 7 | - | Yes | Nissen | 6-24 | 0/7 | - |

| Ma et al[17] | 40 | I 1 (3), II (4), III (15), IV (8) | Yes | Toupet/Dor | 3-25 | 0/40 | 6 dysphagia |

| Zhao et al[18] | 25 | All > 6 cm | Yes | Nissen/Toupet/Dor | 3-35 | 1 (1)/251 | 6 dysphagia, 1 PPI treatment |

| Xu et al[19] | 3 | 13-18 cm | Yes | Toupet | 6-12 | 0/3 | - |

| Zhang et al[20] | 21 | I 1 (4), II (5), III(2) | Yes | Toupet | 6-36 | 0/21 | - |

| Zou et al[21] | 20 | All > 6 cm | Yes | Dor | > 12 | 2 (5)/201 | - |

| Yao et al[22] | 33 | I (5), II (23), III(5) | Yes | Nissen | > 12 | 1 (10)/331 | 3 dysphagia, 1 gastric retention |

| Li et al[23] | 4 | - | Yes | Nissen/Toupet | 1-36 | 0/4 | - |

| Fei et al[24] | 12 | < 5 cm (10), > 5 cm (2) | Yes | Nissen | 12 | 0/12 | 1 dysphagia |

A survey on the use of mesh for HH repair by members of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) showed that 33% preferred nonabsorbable to absorbable mesh[25]. This reflects the fact that prosthetic mesh has the advantage of reducing HH recurrence; biomaterial tends to be associated with failure[9]. On the other hand, concerns still exist regarding mesh-related complications, including erosion, stricture, and fibrosis. Thus, there may be a trade-off in the choice of mesh repair for HH: permanent mesh risks erosion, while biologic mesh risks recurrence[9].

Crurasoft® has the advantages of permanent mesh, while reducing mesh-related complications. Chilintseva et al[10] reported 38 cases who underwent HH repair using Crurasoft®, with no recurrences. Priego et al[26] concluded that Crurasoft®-reinforced hiatoplasty reduced HH recurrence in patients with large hiatal defects (larger than 5 cm), similar to that in patients with smaller hiatal defects (2% vs 2.1%). Granderath et al[27] selected a tailoring strategy for HH repair according to hiatal surface area (HAS). Those with HAS larger than 8 cm2 underwent Crurasoft® placement in a tension-free, posterior onlay fashion. During a mean follow-up period of 6.3 mo, only 1 patient (1.8%) developed postoperative partial intrathoracic wrap migration. In the Chinese literature review, recurrence was between 0% and 10% (Table 3). The highest recurrence rate (2/20, 10%) was reported by Zou et al[21], in whose series all HH were large, with orifices larger than 6 cm or herniation of more than half of the stomach. In our study cohort, we found a type IIHH anatomic recurrence. Paraesophageal herniation is a complication that occurs in the immediate postoperative period following laparoscopic antireflux surgery, with an incidence of up to 7%. Vomiting in the early post-operative period, which occurred in this patient, has been identified as a risk factor for recurrence[3]. Violent diaphragmatic movements might also dislodge the mesh if fixation is inadequate[7]. Sufficient fixation of the mesh and avoidance of lifting or straining have been advocated to reduce this complication.

Two patients suffered symptomatic recurrence without any proof of anatomic recurrence. Both patients underwent Nissen fundoplication and the barium meal examination showed an intact wrap. A possible explanation for this could be poor correlation between postoperative symptoms and actual reflux[28]. Both patients presented with heartburn and acid regurgitation, the cardinal symptoms of GERD. However, these symptoms have a low specificity and sensitivity for the actual diagnosis of GERD. One patient agreed to resume manometry and pH monitoring, and all data indicated an improvement compared with that before surgery. As postoperative GERD symptoms actually indicate acid reflux in only 30% of patients and are not even accurate to rule out acid reflux in patients who are completely free of symptoms after surgery, Khajanchee et al[28] insisted that surgeons should explain the presence of symptomatic recurrence cautiously and that objective testing should be introduced to determine the actual cause.

In a collection of case reports pertaining to mesh complications after prosthetic hiatoplasty with special emphasis on mesh erosion, Stadlhuber et al[7] identified 17 cases of intraluminal erosion, involving not only different mesh material (polypropylene, PTFE, and biomaterial), but also different mesh configurations (keyhole, horseshoe and heart shaped). No apparent relationship between these parameters and mesh erosion was observed, thus the technique for mesh fixation was questioned. Fixation techniques such as the proximity of placement of the mesh at the esophagus are important factors in the development of postoperative complications. The edge of the mesh may “cheese wire” its way into the esophagus if it touches the esophagus or if shrinkage occurs. It is also possible that the mesh can migrate if fixation is insufficient, or traumatic events such as vomiting or repeated coughing may dislodge the mesh, causing it to be apposed to the esophageal wall, leading to erosion or stricture[7]. Use of Crurasoft® cannot completely eliminate this complication. In one case report, total migration of Crurasoft® into the stomach was detected by endoscopy 2 years after repeat fundoplication[29]. Both our series and a review of the Chinese literature failed to disclose any cases of this complication. However, a case of erosion was discussed at a conference without confirmation of its exact source and details (personal communication). Thus, the exact incidence of this complication may be underestimated[7,11].

As opposed to erosion, esophageal stricture due to fibrosis associated with the prosthesis, may be a more common complication. Although ePTFE is less fibrogenic and is designed to prevent contact between the mesh and viscera, severe fibrosis enveloping the mesh can develop, leading to stricture refractory even to endoscopic dilatation[10]. Even though Wassenaar’s recommendations to maintain a 2-3 mm distance between the mesh and esophagus were followed, postoperative dysphagia cannot be completely eliminated (38.10% in our cohort). Only 2 patients had permanent symptoms, due to stricture at the hiatus and not the fundoplication itself (confirmed radiographically). Fortunately, most of these patients presented with mild dysphagia, which resolved within the first postoperative year, and did not require reoperation.

In conclusion, the use of Crurasoft® mesh for HH repair results in satisfactory symptom control with a low recurrence rate. Postoperative dysphagia continues to be an issue, and requires more research to reduce its incidence.

Cryoplasty is considered to be an essential part of antireflux surgery and use of a mesh, either by reducing tension or reinforcing the crural musculature, is associated with a significantly lower recurrence rate. Despite this, most concerns are focused on mesh-related complications.

Prosthetic mesh-related complications, including intraluminal erosion, fibrosis, and esophageal stenosis may be more common than reported. Moreover, surgery to manage these complications is complex and may require esophagectomy or gastrectomy. The ideal mesh generates adhesion to the diaphragmatic surface and not the visceral side.

“V” shaped composite polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) prostheses (dual-sided composite mesh, Crurasoft®) might be an ideal mesh. PTFE encourages ingrowth of host tissue from the underlying crura, producing local fibrosis and a more uniform mesh-tissue complex. ePTFE was thought to have a benign behavior as opposed to hollow viscera, with encapsulation of the material and neomesothelialization of the abdominal exposed surface, thus becoming isolated from the esophagus and stomach.

Crurasoft® is the most commonly used prosthetic mesh in China. The authors summarize their experience in the application of Crurasoft® for antireflux surgery, focusing on whether reduction of postoperative complications, especially erosion and dysphagia, can be achieved if technical attention to mesh fixation is applied.

Clinical study and review by the authors demonstrate the benefit of the mesh Crurasoft in surgical therapy of hiatal hernia. The study is of clinical interest.

P- Reviewer Gassler N S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Zaninotto G, Portale G, Costantini M, Fiamingo P, Rampado S, Guirroli E, Nicoletti L, Ancona E. Objective follow-up after laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia. Assessment of safety and durability. World J Surg. 2007;31:2177-2183. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Antoniou SA, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Hiatal hernia repair with the use of biologic meshes: a literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Antoniou SA, Koch OO, Kaindlstorfer A, Asche KU, Berger J, Granderath FA, Pointner R. Endoscopic full-thickness plication versus laparoscopic fundoplication: a prospective study on quality of life and symptom control. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1063-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soricelli E, Basso N, Genco A, Cipriano M. Long-term results of hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2499-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Müller-Stich BP, Holzinger F, Kapp T, Klaiber C. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair: long-term outcome with the focus on the influence of mesh reinforcement. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:380-384. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hiles M, Record Ritchie RD, Altizer AM. Are biologic grafts effective for hernia repair: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Innov. 2009;16:26-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK, Fitzgibbons RJ, Michael Brunt L, Hunter JG, Demeester TR, Swanstrom LL, Daniel Smith C, Filipi CJ. Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1219-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morino M, Giaccone C, Pellegrino L, Rebecchi F. Laparoscopic management of giant hiatal hernia: factors influencing long-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1011-1016. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Frantzides CT, Carlson MA, Loizides S, Papafili A, Luu M, Roberts J, Zeni T, Frantzides A. Hiatal hernia repair with mesh: a survey of SAGES members. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1017-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chilintseva N, Brigand C, Meyer C, Rohr S. Laparoscopic prosthetic hiatal reinforcement for large hiatal hernia repair. J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e215-e220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wassenaar EB, Mier F, Sinan H, Petersen RP, Martin AV, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK. The safety of biologic mesh for laparoscopic repair of large, complicated hiatal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1390-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, Soper N, Brunt M, Sheppard B, Jobe B, Polissar N, Mitsumori L, Nelson J. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244:481-490. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chu HB, Xu YB, Qiu M, Jiang DZ, Li K, Cai YQ, Yan F. Laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia with polypropylene and polytetrafluoroethlene. Zhonghua Qiangjing Waike Zazhi (Electronic Edition). 2011;4:20-23. |

| 14. | Wang TS, Zhu B, Gong K, Lu YP, Wang Y, Amin BH, Zhao X, Lian DB, Zhang DD, Fan Q. Laparoscopic hiatoplasty for hiatal hernia (15 cases reports). Zhongguo Neijing Zazhi. 2011;17:425-427. |

| 15. | Tai QW, Zhang JH, Wen H, Pa EH, Zhang J, Ding HT. Clinical evaluation of laparoscopic esophageal hiatal hernia repair. Zhonghua Shanhefubi Waike Zazhi (Electronic Edition). 2011;5:12-14. |

| 16. | Ji ZL, Li JS, You CZ. Jin D. Clinical analysis of laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia. Fuqiangjing Waike Zazhi. 2010;15:578-580. |

| 17. | Ma B, Tian W, Chen L, Liu PF. Laparoscopic tension-free repair for the esophageal hiatal hernia. Keji Daobao. 2010;28:28-30. |

| 18. | Zhao HZ, Qin MF. Laparoscopic repair of giant hiatal hernia: analysis of 25 case. Zhonghua Xiongxinxueguan Waike Zazhi. 2011;27:152-154. |

| 19. | Xu D, Wu SD, Su Y, Li LY. Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageaI hernia with patch appIicatjon: an analysis of 3 cases. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2009;17:1868-1870. |

| 20. | Zhang KJ. Clinical analysis of laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia.with mesh reinforcement. Zhongguo Linchuang Shiyong Yixue. 2010;4:131-132. |

| 21. | Zou FS, Qin MF, Cai W, Zhao HZ. Laparoscopic mesh for massive esophageal hiatal hernia. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2010;27:636-638. |

| 22. | Yao GL, Yao QY, Hua R, Yu JP. Effect of biologic mesh for hiatal hernia repair: one year follow-up. Zhongguo Zuzhi Gongcheng Yanjiu Yu Linchuang Kangfu. 2011;15:491-494. |

| 23. | Li Q, Qu SX, Xie GW. Laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair: a clinical analysis of 12 case. Fuqiangjing Waike Zazhi. 2012;17:752-754. |

| 24. | Fei Y, Li JY. Investigation of application of laparoscopic hiatus reconstruction with Crurosoft patch in elderly patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Zhongguo Puwai Jichu Yu Linchuang Zazhi. 2011;18:866-870. |

| 25. | Pfluke JM, Parker M, Bowers SP, Asbun HJ, Daniel Smith C. Use of mesh for hiatal hernia repair: a survey of SAGES members. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1843-1848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Priego P, Ruiz-Tovar J, Pérez de Oteyza J. Long-term results of giant hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery for gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:139-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Granderath FA, Schweiger UM, Pointner R. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: tailoring the hiatal closure to the size of hiatal surface area. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:542-548. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Khajanchee YS, O’Rourke RW, Lockhart B, Patterson EJ, Hansen PD, Swanstrom LL. Postoperative symptoms and failure after antireflux surgery. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1008-1013; discussion 1013-1014. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Carpelan-Holmström M, Kruuna O, Salo J, Kylänpää L, Scheinin T. Late mesh migration through the stomach wall after laparoscopic refundoplication using a dual-sided PTFE/ePTFE mesh. Hernia. 2011;15:217-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |