Published online Sep 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5513

Revised: June 17, 2013

Accepted: July 17, 2013

Published online: September 7, 2013

Processing time: 175 Days and 9.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the clinical advantages of the stent-laparoscopy approach to treat colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with acute colorectal obstruction (ACO).

METHODS: From April 2008 to April 2012, surgery-related parameters, complications, overall survival (OS), and disease-free survival (DFS) of 74 consecutive patients with left-sided CRC presented with ACO who underwent self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) placement followed by one-stage open (n = 58) or laparoscopic resection (n = 16) were evaluated retrospectively. The stent-laparoscopy group was also compared with a control group of 96 CRC patients who underwent regular laparoscopy without ACO between January 2010 and December 2011 to explore whether SEMS placement influenced the laparoscopic procedure or reduced long-term survival by influencing CRC oncological characteristics.

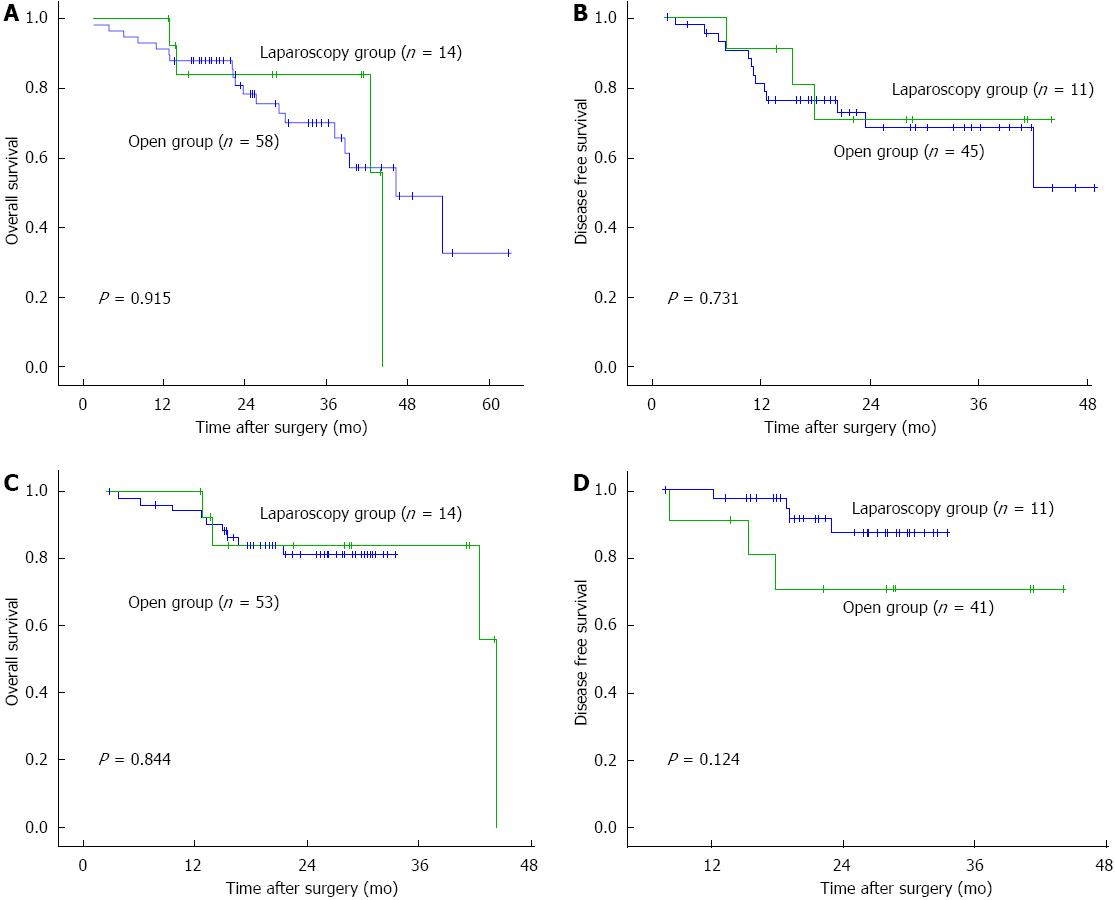

RESULTS: The characteristics of patients among these groups were comparable. The rate of conversion to open surgery was 12.5% in the stent-laparoscopy group. Bowel function recovery and postoperative hospital stay were significantly shorter (3.3 ± 0.9 d vs 4.2 ± 1.5 d and 6.7 ± 1.1 d vs 9.5 ± 6.7 d, P = 0.016 and P = 0.005), and surgical time was significantly longer (152.1 ± 44.4 min vs 127.4 ± 38.4 min, P = 0.045) in the stent-laparoscopy group than in the stent-open group. Surgery-related complications and the rate of admission to the intensive care unit were lower in the stent-laparoscopy group. There were no significant differences in the interval between stenting and surgery, intraoperative blood loss, OS, and DFS between the two stent groups. Compared with those in the stent-laparoscopy group, all surgery-related parameters, complications, OS, and DFS in the control group were comparable.

CONCLUSION: The stent-laparoscopy approach is a feasible, rapid, and minimally invasive option for patients with ACO caused by left-sided CRC and can achieve a favorable long-term prognosis.

Core tip: Our study compared long-term survival between left-sided colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with acute colorectal obstruction (ACO) who had undergone self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) placement followed by one-stage laparoscopic (stent-laparoscopy group) and open resection (stent-open group). Long-term survival in left-sided CRC patients without ACO who had undergone laparoscopic resection (control group) was compared with the stent-laparoscopy group. A stent-laparoscopy approach did not reduce long-term survival by influencing CRC oncological characteristics. Surgery-related parameters and postoperative complications in the stent-laparoscopy group were also compared with those of the other two groups; the results indicated that SEMS placement did not influence subsequent laparoscopic procedures.

- Citation: Zhou JM, Yao LQ, Xu JM, Xu MD, Zhou PH, Chen WF, Shi Q, Ren Z, Chen T, Zhong YS. Self-expandable metallic stent placement plus laparoscopy for acute malignant colorectal obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(33): 5513-5519

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i33/5513.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5513

Acute colorectal obstruction (ACO) is one of the common initial symptoms in patients with left-sided colorectal cancer (CRC). Emergent surgery is a conventional treatment, but it is usually associated with high morbidity, mortality, and stoma rate[1-3]. Since 1991, self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS) placement has been applied to relieve ACO caused by left-sided CRC and is effective in restoring colorectal transit, allowing sufficient preoperative preparation and tumor stage evaluation[4-6]. Compared with emergent surgery, preoperative stenting and elective surgery are safer and increase the probability of one-stage resection[7,8]. Open and laparoscopic colectomies are two recent approaches used as a subsequent elective surgery following successful SEMS placement. Laparoscopic colectomy has a lower postoperative complication rate and a shorter hospital stay[9]. The application of SEMS placement can increase the probability of performing laparoscopic colectomy and offers the advantages of two minimally invasive procedures[10]. The stent-laparoscopy approach was first introduced by Morino et al[11] in 2002, and its use has been reported in previous studies[12-18]. In Morino’s study, preoperative SEMS placement was believed to make the laparoscopic procedure more difficult and the colonic segment more bulky and more technically difficult to remove through laparoscopy[10], but this has not been confirmed. Similarly, the long-term survival of patients undergoing stent-laparoscopy is currently unknown. Therefore, the present study was designed to compare surgery-related parameters, including surgical time and intraoperative blood loss, postoperative complications, long-term overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS), of the stent-laparoscopy approach with the stent-open surgery approach in left-sided CRC patients with ACO and with regular laparoscopy in left-sided CRC patients without ACO to determine the clinical advantages and long-term prognoses of the stent-laparoscopy approach and the influence of preoperative SEMS placement on the laparoscopic procedure.

From April 2008 to April 2012, 74 consecutive patients (47 males and 27 females, aged 34-84 years, median 60 years) with left-sided CRC and ACO, who had undergone SEMS placement followed by one-stage resection at Zhongshan Hospital, were reviewed retrospectively. The obstruction was diagnosed clinically and radiologically. Patient symptoms were abdominal pain and fullness, vomiting and constipation. Physical examination showed a distended and tympanic abdomen. Abdominal X-ray revealed a distended large bowel and an air-fluid level. All patients underwent endoscopic SEMS placement to release the obstruction. According to the particular subsequent resection approach selected by the attending surgeon, patients were allocated into the stent-laparoscopy group and the stent-open group. Additionally, from January 2010 to December 2011, 96 left-sided CRC patients without ACO who had undergone one-stage laparoscopic resection were enrolled consecutively as the control group. All patients were enrolled after informed consent. The Research Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital approved the study.

After surgery, the follow-up procedures in the stent-surgery groups, including chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography scan and blood tests, especially levels of cancer embryo antigen, were performed every 3 to 4 mo within 2 years, and continued every 4 to 6 mo for 3 to 4 years thereafter. Colonoscopy was performed every 6 mo in the first year and every year for 2 to 4 years. Tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 6th edition. OS was defined as the interval between SEMS placement and death or the last follow-up visit. DFS was defined as the interval between SEMS placement and recurrence or postoperative remote organ metastasis. If recurrence was not diagnosed, patients were censored on the date of death or last follow-up.

Briefly, all SEMS placement procedures were performed by one of five experienced endoscopists using a coloscope (CF-260I; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with fluoroscopic guidance. Water-soluble contrast material was injected through the catheter to visualize the stricture. The size of the SEMS was selected according to the length and caliber of the stricture (diameter, 26 mm; length, range 50-100 mm). The length of the SEMS was at least an additional 2 cm on each side of the stricture. A SEMS from MicroTech (MicroTech Co., Nanjing, China) or Boston Scientific (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) was used according to the endoscopist’s preference. After deployment, the proper position and expansion of the SEMS was assessed using fluoroscopic visualization.

After complete remission of ACO, bowel preparation was performed with polyethylene glycol 24 h before surgery. Patients were placed in the Trendelenburg position, and slightly tilted to the right and downward. The target colorectum and its mesentery were mobilized laparoscopically, and the colon distal to the tumor was divided using endo linear staplers. A vertical periumbilical incision was made to remove the specimen and introduce the anvil of the circular stapler. An anastomosis was made in an end-to-end manner using the circular stapler or in a side-to-side manner using the double staples method to discriminate the size of the colorectal lumen.

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. An unpaired t test was used to compare quantitative variables. A Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to compare qualitative variables. The patients’ survival curve was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to determine the significant differences between groups. Analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All images were edited using Photoshop CS5 extended (Adobe, San Jose, CA, United States).

Sixteen patients were in the stent-laparoscopy group and 58 patients were in the stent-open group. In the stent-laparoscopy group, two patients (12.5%) converted to open surgery for abdominal carcinomatosis and serious local intestinal adhesions; both conditions were unrelated to the stenting. In the control group, the rate of conversion to open surgery was 8.3% (8/96); three for serious local intestinal adhesions, four for extensive tissue invasion of the tumor and one for an inappropriate tumor site, which was not significantly different from the stent-laparoscopy group. These patients were excluded from the analyzed data. The patient characteristics were comparable among the three groups (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Stent-laparoscopy | Stent-open | Control |

| Conversion to open surgery n (%) | 2 (12.5) | - | 8 (8.3) |

| Patients | 14 | 58 | 88 |

| Age (yr) | 57.7 ± 9.6 | 60.2 ± 12.8 | 59.6 ± 10.1 |

| Gender (male/female) | 10/4 | 36/22 | 53/35 |

| Site of obstruction | |||

| Descending colon | 4 | 15 | 13 |

| Sigmoid colon | 7 | 26 | 51 |

| Rectum | 3 | 17 | 24 |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| II | 6 | 24 | 37 |

| III | 5 | 21 | 27 |

| IV | 3 | 12 | 19 |

The mean interval between stenting and surgery in the stent-open and stent-laparoscopy groups were 10.6 and 13.9 d, respectively (P = 0.397), and 8.8 and 10.2 d (P = 0.162), respectively, after the patients who received preoperative chemotherapy were excluded. No intraoperative morbidity was observed in either group. The mean surgical time in the stent-laparoscopy group was significantly longer than in the stent-open group (152.1 min vs 127.4 min, P = 0.045). However, intraoperative blood loss was not significantly different (P = 0.530). After surgery, mean bowel function recovery and postoperative hospital stay in the stent-laparoscopy group were significantly shorter than those in the stent-open group (3.3 d vs 4.2 d and 6.7 d vs 9.5 d, P = 0.016 and P = 0.005, respectively). In the stent-open group, 20.7% (12/58) of patients were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) after surgery, whereas none were admitted to the ICU in the laparoscopy group. No postoperative complications were observed in the stent-laparoscopy group, whereas seven patients (12.1%) with postoperative complications were observed in the stent-open group (Table 2).

| Stent-laparoscopy | Stent-open | Control | |

| Interval between stenting and surgery (d) | 13.9 ± 13.2 | 10.6 ± 13.3 | - |

| Operation time (min) | 152.1 ± 44.4 | 127.4 ± 38.4a | 152.3 ± 40.8 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 54.3 ± 63.0 | 77.4 ± 132.7 | 77.1 ± 41.4 |

| Bowel function recovery (d) | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 1.5a | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 6.7 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 6.7a | 6.3 ± 3.5 |

| Admitted to ICU n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (20.7) | 8 (9.1) |

| Postoperative complications | |||

| Incision rupture | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Incision infection | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Adhesive intestinal obstruction | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Postoperative stroke | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Compared with the control group, surgery-related parameters, including surgical time, intraoperative blood loss, bowel function recovery, and postoperative hospital stay, were comparable in the stent-laparoscopy group. In the control group, eight patients (9.1%) were admitted to the ICU after surgery and postoperative complications occurred in two patients (2.3%) (Table 2).

The long-term survival of patients in the three groups was investigated. The follow-up period of patients in the stent-laparoscopy group was 28.2 ± 13.0 mo, which was not significantly different from that of the stent-open group (28.9 ± 13.8 mo, P = 0.865) and the control group (22.2 ± 7.9 mo, P = 0.118), respectively. Patients with TNM stage IV were excluded from the DFS analysis. The 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-year OS and DFS of patients in the stent-laparoscopy group were 100%, 83%, 83%, and 36%, and 91%, 71%, 71%, and 71%, respectively, which were not significantly different from those of the stent-open group (91%, 79%, 70%, and 50%; and 82%, 70%, 70%, and 57%, respectively, P = 0.915 and P = 0.731; Figure 1A and B). The 1-, 2-, and 3-year OS and DFS of patients in the control group were 94%, 80%, and 80%, and 100%, 88%, and 88%, respectively (P = 0.844 and P = 0.124; Figure 1C and D), which were also not significantly different from those of the stent-laparoscopy group. At the end of this study, 10 patients in the stent-laparoscopy group, 39 patients in the stent-open group, and 44 patients in control group remained alive. The details of recurrence, metastasis, and treatment are shown in Table 3 (Figure 2 shows a surgical specimen containing an SEMS).

Malignant ACO was considered a relative contraindication of laparoscopy because of an unprepared fragile bowel and insufficient working space caused by the distended bowel, until SEMS placement was extended from a palliative treatment to a “bridge to surgery” treatment[19]. Meanwhile, the surgical approach to malignant ACO has changed extensively over time. The traditional three-stage operation was replaced gradually by a one-stage resection with primary anastomosis[11]. Preoperative SEMS placement also dramatically increases the probability of subsequent one-stage resection, using either an open or laparoscopic approach[7,20]. Morino et al[11] first reported four left-sided CRC patients with ACO who were treated by a stent-laparoscopy approach. Although positive conclusions could be drawn, the lack of both an appropriate control group and long-term outcomes, as well as a limited number of patients made further study necessary. Likewise, other studies reported conflicting results. Thus, the present larger, long-term follow-up study aimed to report our experience and discuss the issues in previous studies by comparing the stent-laparoscopy approach with the stent-open approach and regular laparoscopy.

As the first step of the stent-laparoscopy approach, preoperative SEMS placement generally has a high success rate[8]. The technical and clinical success rates of SEMS placement are more than 96.7% and more than 90%, respectively. Moreover, no SEMS placement-associated morbidity or mortality was observed[11-17]. The technical and clinical success rates of patients in our center since 2005 were also similar to the data in these previous studies. A high success rate and low risk of preoperative SEMS placement guarantee the feasibility of the stent-laparoscopy approach.

For the laparoscopy procedure, several controversial issues have been reported in previous studies. Balagué et al[12] first suggested that the rigidity of the colonic segment containing the stent and the tumor made dissection more difficult than usual, prolonging the surgical time. In the same year, Law et al[13] reported that laparoscopic mobilization was not particularly difficult and the amount of blood loss was low. Following these studies, the results of study of Chung et al[17] partly supported Law’s conclusions; the data from eight stent-open group patients were similar to those of the 17 stent-laparoscopy patients in terms of surgical time, estimated blood loss, and other surgery-related and postoperative parameters. In our study, intraoperative blood loss was not significantly different between the stent-laparoscopy and stent-open approaches, or regular laparoscopy, supporting Chung’s conclusions and indicating the favorable safety of the stent-laparoscopy approach. However, the surgical times were not completely consistent with those reported in the above-mentioned studies. We found that compared with the stent-open approach, the stent-laparoscopy approach significantly prolonged the surgical time. When we compared the stent-laparoscopy approach with regular laparoscopy, no significant differences in the surgical times between these two groups were observed. Moreover, the rate of conversion to open surgery in the stent-laparoscopy approach was 12.5%, which was similar to 8.3% in regular laparoscopy, and the two causes of conversion were related to the tumor or abdominal conditions (tumor invasion and intestinal adhesions), but unrelated to preoperative SEMS placement. Thus, we confirmed that the major influences on subsequent surgical procedures after stenting were the difficulties from the laparoscopy itself, and tumor or abdominal conditions, but not preoperative SEMS placement. Additionally, skilled surgeons performed all of the surgical procedures in our study, so a technical bias could be excluded.

Regarding postoperative recovery, bowel function recovery and postoperative hospital stays for the stent-laparoscopy group were significantly shorter than those for the stent-open group, and were similar to those of the regular laparoscopy group. Furthermore, no postoperative complications were observed for the stent-laparoscopy group, which was similar to that of the regular laparoscopy group, but fewer than the 12.1% in the stent-open group. Our results also indicated that using the stent-laparoscopy approach was associated with faster recovery and lower postoperative morbidity, which was similar to the results of previous studies[16,17,21-23].

Long-term survival in these three groups was compared to estimate the curative effect of the stent-laparoscopy approach. Previously, Stipa et al[16] reported that their minimum follow-up period was 15 mo, and 17/22 (77%) surgically treated patients (six patients in the stent-open group and 16 in the stent-laparoscopy group) were alive at the end of their study. In Dulucq’s study, neither recurrences nor port-site metastases were observed during a follow-up period of 11 ± 7 mo[14]. Similarly, Olmi et al[15] reported that after a median 36-mo follow-up period, all 19 patients in the stent-laparoscopy group and four patients in the stent-open group were alive. The superiority of laparoscopic colectomy for treating malignancy over open surgery in terms of recurrence and cancer-related survival was demonstrated in a previous randomized trial[24]. In several recent, large-scale randomized control trials (RCTs), no significant differences in 3- or 5-year OS and DFS between laparoscopy and open surgery were observed[21]. In the present study, 4-year OS and DFS were compared between laparoscopy and open surgery after SEMS placement, and no significant differences were observed, in accordance with the results of these RCTs. Thus, we suggest that different surgical approaches after stenting do not influence long-term clinical outcomes. On the other hand, no study had explored whether a preoperative SEMS influenced the curative effect of subsequent laparoscopy for exacerbating CRC oncological characteristics, such as promoting recurrence or metastasis. Therefore, we compared long-term OS and DFS between the stent-laparoscopy approach and regular laparoscopy, and no significant differences were observed. These results indicate that preoperative SEMS placement is completely safe for subsequent laparoscopy.

In conclusion, compared with the stent-open approach, the stent-laparoscopy approach was associated with a more difficult surgical procedure, but a faster postoperative recovery and lower morbidity. These two approaches show similar long-term survival, recurrence rates and metastasis rates. Furthermore, after comparison with regular laparoscopy, preoperative SEMS placement does not influence subsequent laparoscopic procedures and long-term survival could be assessed. Therefore, SEMS placement followed by one-stage laparoscopic surgery is a feasible and rapid recovery treatment option for patents with ACO caused by left-sided CRC, and provides a favorable long-term prognosis. Of course, this study is limited by the patients’ conditions and the study method employed; thus, heterogeneity among the groups in our study cannot be excluded. A larger number of patients, a longer follow-up period and more homogeneous study groups should be included in a future study.

Acute colorectal obstruction (ACO) is a common initial symptom in patients with left-sided colorectal cancer (CRC). Placement of a self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS), followed by elective surgery, will gradually replace conventional treatment (emergent surgery), and become the predominant treatment. Meanwhile, the application of a SEMS enhances the need for laparoscopic colectomy, avoiding colostomy, and offers the advantages of two minimally invasive procedures.

SEMS placement followed by laparoscopy is an emerging and accepted treatment for left-sided CRC patients with ACO. However, preoperative SEMS placement is believed to make the laparoscopic procedure more difficult, because the SEMS make the colonic segment more bulky and more technically difficult to remove via laparoscopy. In addition, long-term clinical outcomes of the stent-laparoscopy approach are unknown.

Authors compared surgery-related parameters, postoperative complications, and long-term survival using the stent-laparoscopy approach with those using the stent-open approach and regular laparoscopy in left-sided CRC patients without ACO. They first reported that preoperative SEMS placement did not influence any subsequent laparoscopic procedure. Furthermore, using a stent-laparoscopy approach could achieve a similar curative effect compared with the other two approaches and did not reduce long-term survival of patients by influencing CRC oncological characteristics.

The results indicate that SEMS placement followed by one-stage laparoscopic surgery is a feasible treatment option for left-sided CRC patients with ACO, and shows rapid recovery. Moreover, the treatment does not reduce long-term survival by influencing CRC oncological characteristics, which confirms the curative effect of the stent-laparoscopy approach and may allow it to be applied more widely.

SEMS placement: a SEMS is placed in the stricture of the ACO to drain the excrement.

This study details the clinical outcomes and long-term survival of patients undergoing preoperative SEMS placement and laparoscopy. The results show that the stent-laparoscopy approach is a feasible treatment for left-sided CRC patients with ACO, with rapid recovery and good long-term prognosis.

P- Reviewers Chow WK, Hussain A, Li B, Simone G S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Bhardwaj R, Parker MC. Palliative therapy of colorectal carcinoma: stent or surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:518-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feo L, Schaffzin DM. Colonic stents: the modern treatment of colonic obstruction. Adv Ther. 2011;28:73-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scott NA, Jeacock J, Kingston RD. Risk factors in patients presenting as an emergency with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:321-323. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Khot UP, Lang AW, Murali K, Parker MC. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1096-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2051-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Watt AM, Faragher IG, Griffin TT, Rieger NA, Maddern GJ. Self-expanding metallic stents for relieving malignant colorectal obstruction: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2007;246:24-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ho KS, Quah HM, Lim JF, Tang CL, Eu KW. Endoscopic stenting and elective surgery versus emergency surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a prospective randomized trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:355-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang Y, Shi J, Shi B, Song CY, Xie WF, Chen YX. Self-expanding metallic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for obstructive colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kang CY, Chaudhry OO, Halabi WJ, Nguyen V, Carmichael JC, Stamos MJ, Mills S. Outcomes of laparoscopic colorectal surgery: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2009. Am J Surg. 2012;204:952-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Farrell JJ. Preoperative colonic stenting: how, when and why. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:544-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morino M, Bertello A, Garbarini A, Rozzio G, Repici A. Malignant colonic obstruction managed by endoscopic stent decompression followed by laparoscopic resections. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1483-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Balagué C, Targarona EM, Sainz S, Montero O, Bendahat G, Kobus C, Garriga J, Gonzalez D, Pujol J, Trias M. Minimally invasive treatment for obstructive tumors of the left colon: endoluminal self-expanding metal stent and laparoscopic colectomy. Preliminary results. Dig Surg. 2004;21:282-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, Chu KW. Laparoscopic colectomy for obstructing sigmoid cancer with prior insertion of an expandable metallic stent. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2004;14:29-32. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Beyssac R, Barberis C, Talbi P, Mahajna A. One-stage laparoscopic colorectal resection after placement of self-expanding metallic stents for colorectal obstruction: a prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2365-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Olmi S, Scaini A, Cesana G, Dinelli M, Lomazzi A, Croce E. Acute colonic obstruction: endoscopic stenting and laparoscopic resection. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2100-2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stipa F, Pigazzi A, Bascone B, Cimitan A, Villotti G, Burza A, Vitale A. Management of obstructive colorectal cancer with endoscopic stenting followed by single-stage surgery: open or laparoscopic resection. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1477-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chung TS, Lim SB, Sohn DK, Hong CW, Han KS, Choi HS, Jeong SY. Feasibility of single-stage laparoscopic resection after placement of a self-expandable metallic stent for obstructive left colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2008;32:2275-2280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gross KN, Francescatti AB, Brand MI, Saclarides TJ. Surgery after colonic stenting. Am Surg. 2012;78:722-727. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Mainar A, De Gregorio Ariza MA, Tejero E, Tobío R, Alfonso E, Pinto I, Herrera M, Fernández JA. Acute colorectal obstruction: treatment with self-expandable metallic stents before scheduled surgery--results of a multicenter study. Radiology. 1999;210:65-69. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Iversen LH, Kratmann M, Bøje M, Laurberg S. Self-expanding metallic stents as bridge to surgery in obstructing colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:275-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hoffman GC, Baker JW, Fitchett CW, Vansant JH. Laparoscopic-assisted colectomy. Initial experience. Ann Surg. 1994;219:732-740; discussion 740-743. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Piqué JM, Delgado S, Campo E, Bordas JM, Taurá P, Grande L, Fuster J, Pacheco JL. Short-term outcome analysis of a randomized study comparing laparoscopic vs open colectomy for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:1101-1105. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lee JK, Delaney CP, Lipman JM. Current state of the art in laparoscopic colorectal surgery for cancer: Update on the multi-centric international trials. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2012;6:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, Castells A, Taurá P, Piqué JM, Visa J. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1901] [Cited by in RCA: 1813] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |