INTRODUCTION

Primary aortoduodenal fistula (PADF) is a rare, challenging complication of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). PADF is an abnormal communication between the infrarenal aorta and duodenum, whereas secondary aortoduodenal fistula usually results from a previously implanted endovascular stent-graft procedure[1]. Since their first description about 100 years ago, more than 200 PADFs have been reported in the world literature[2-4]. They are usually found between the 3rd part of the duodenum and infrarenal aorta, caused by evolutionary complication of an aortic aneurysm[5]. Although less frequent, this abnormal communication also occurs between the aorta and other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, namely the esophagus, jejunum, ileum, or colon. The rarity of PADFs poses major diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties to the treating physicians.

The present case report describes a PADF between the infrarenal AAA and fourth part of the duodenum, which was successfully managed at King Khalid Hospital, Najran, Saudi Arabia.

CASE REPORT

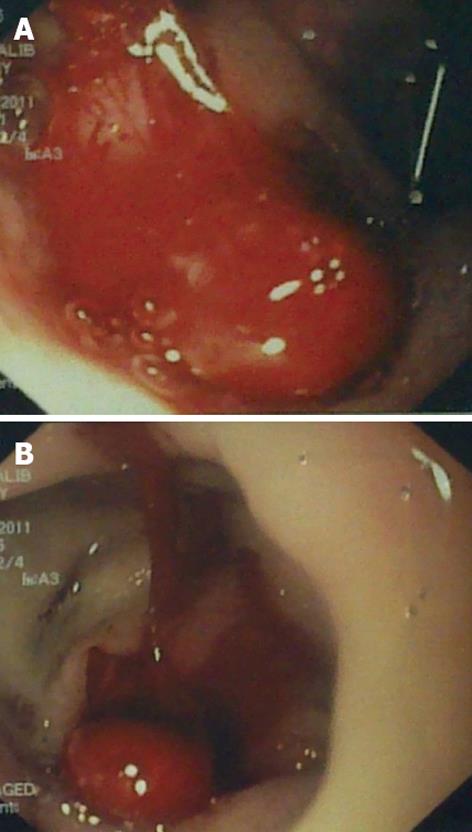

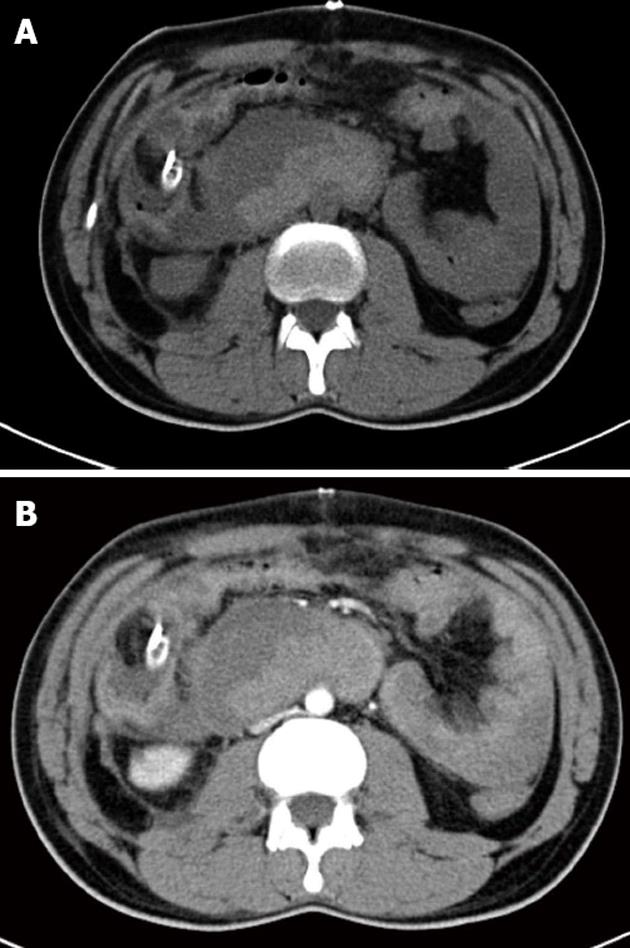

A 47-year-old Saudi male presented to the emergency room of King Khalid Hospital Najran, Saudi Arabia with a 6-h history of massive fresh upper GI bleeding. He was a heavy smoker with no notable medical history. On examination, he had normal sensorium, pulse 113 beats/min, blood pressure 90/70 mmHg, and a cold sweaty skin. The laboratory investigations showed hemoglobin (Hb) 9.3 g/dL, white cell count 7100/mm3, while electrolytes, renal and coagulation profiles, serum amylase and liver function testes were normal. The abdominal examination was unremarkable except for tenderness in the epigastrium. After initial resuscitation, upper GI endoscopy was performed and showed a huge amount of fresh blood emanating from the duodenum (Figure 1). No definite source of the bleeding could be identified. The patient was admitted in the intensive care unit, where, despite massive blood transfusion and active fluid resuscitation, the patient remained hemodynamically unstable, fresh bleeding continued in the nasogastric tube, and Hb dropped to 6.7 g/dL. On the 2nd post-admission day, the responsible consultant surgeon performed an exploratory laparotomy which revealed a distended duodenum and no blood in the peritoneum. A duodenotomy was performed which drained fresh and clotted blood, but no active source of the bleeding could be delineated. Perioperative upper GI endoscopy could not provide any additional information. Duodenotomy was closed over a tube drain followed by mass closure of the abdomen. Postoperatively, the patient continued to have fresh bleeding in the nasogastric tube. A computer tomography (CT) scan at that stage showed a PADF between the infrarenal aorta and fourth part of the duodenum (Figure 2). The vascular team was consulted and a second exploratory laparotomy was undertaken where the AAA was repaired with a prosthetic Goretex tube graft, and the duodenal fistula was closed in two layers. An omentopexy was performed between the aorta-graft anastomosis and duodenum. The culture and sensitivity report of the aortic wall reported the growth of Klebsiella. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged home in a stable condition. His first follow-up visit in the surgical outpatient clinic, 2 wk after discharge, showed normal parameters.

Figure 1 Endoscopic views of the stomach (A) and duodenum (B) showing a huge amount of fresh blood emerging from a concealed source.

Figure 2 Computer tomography scan showing a primary aortoduodenal fistula between the infrarenal aorta and 4th part of the duodenum.

A: Computer tomography (CT) scan without contrast showing a ruptured aortic aneurysm; B: Arterial phase of the CT scan showing the partially thrombosed abdominal aortic aneurysm.

DISCUSSION

The term PADF was first coined by Cooper[6], and the first case report was described by Salman[7]. The incidence of primary aorto-enteric fistulas is very low and, according to autopsy findings, ranges between 0.04% and 0.07%[8]. Up to December 2006, 366 cases of primary aorto-enteric fistulae have been reported[9]. Regarding the anatomical distribution, the 3rd part of the duodenum is involved in two-thirds of cases while the 4th part is affected in one-third of cases. Because of the close approximation and fixed nature of the duodenum, the expanding nature of the AAA causes irritation and inflammation, resulting in eventual fistulization over the passage of time.

The proposed mechanisms for the development of PADF are direct wear and inflammatory destruction triggered by infection, foreign bodies, or erosion[5]. Eighty percent of PADFs have been estimated to arise from an AAA. Gad reported 73% of PADFs developed from atherosclerotic aneurysms and 26% from traumatic or mycotic aneurysms[10]. The remaining 1% are caused by radiation, pancreatic carcinoma, metastases, ulcers, gallstones, diverticulitis, and appendicitis. The classical presentations of PADFs are upper GI bleeding (64%), abdominal pain (32%), and a pulsatile abdominal mass (25%)[11,12]. Other rare symptoms include intermittent back pain, fever, and sepsis, melena, and syncope. Quite frequently an expansile abdominal mass and a bruit is noticed on abdominal examination.

The most valuable diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of PADF is considered to be helical CT scan with intravenous contrast[13]. Rapid scanning, high resolution, non-invasive procedure, image quality, and data processing are the outright benefits of CT scanning. Loss of the aneurysmal wall, air in the retroperitoneum or thrombus, or destruction of the fat plane between the aneurysm and duodenum strongly suggest a PADF. In addition, visualization of the contrast within the GI tract is a striking CT finding. Other diagnostic modalities include upper GI endoscopy and angiography. Endoscopy is useful in diagnosing upper GI bleeding, although a negative report does not exclude the possibility of a PADF. The visualization of the fistula below the 3rd part of the duodenum is quite difficult due to acute angulation between 3rd and 4th parts of the duodenum[12]. Angiography is not reliable in diagnosing PADF. In a retrospective study, 13 out of 36 aorto-enteric fistulas were diagnosed by angiography before surgery[14]. Magnetic resonance imaging, tagged white blood cell scans, colonoscopy, and ultrasound are of limited value[15].

The mortality from untreated PADF is almost 100%. The survival after surgery ranges from 18% to 93%[16]. The recommended surgical procedure consists of closure of the duodenal fistula, aortic ligation to exclude the aneurysm, and an extraluminal bypass. In the case of an infected AAA, antibiotics should be given for 4-6 wk after surgery, if a positive culture is obtained[17]. The most commonly encountered cultured organisms in primary mycotic PADF are Salmonella and Klebsiella. In our case, third generation cephalosporins were administered for 1 mo with promising results.

To conclude, PADF are an extremely uncommon cause of massive upper GI bleeding and abdominal mass. A CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosis of this entity, and surgical intervention offers the only treatment for survival.