Published online Jan 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.321

Revised: July 16, 2012

Accepted: August 14, 2012

Published online: January 21, 2013

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare but important special type of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with clinicopathological presentation mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and prompt and correct diagnosis can be a challenge, especially in endemic areas with a high incidence of HCC. To date, HAC has only been reported in case series or single case reports, so we aimed to review the clinicopathological characteristics of HAC to obtain a more complete picture of this rare form of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma. All the articles about HAC published from 2001 to 2011 were reviewed, and clinicopathological findings were extracted for analysis. A late middle-aged male with high serum α-fetoprotein and atypical image finding of HCC should raise the suspicion of HAC, and characteristic pathological immunohistochemical stains can help with the differential diagnosis. Novel immunohistochemical markers may be useful to clearly differentiate HAC from HCC. Once metastatic HAC is diagnosed, the primary tumor origin should be identified for adequate treatment. The majority of HAC originates from the stomach, so panendoscopy should be arranged first.

- Citation: Su JS, Chen YT, Wang RC, Wu CY, Lee SW, Lee TY. Clinicopathological characteristics in the differential diagnosis of hepatoid adenocarcinoma: A literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(3): 321-327

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i3/321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i3.321

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare but important special type of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with clinicopathological presentation mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HAC was first reported as an α fetoprotein (AFP)-producing tumor in 1970[1], and Ishikura et al[2,3], in a report of seven AFP-producing gastric adenocarcinomas (GAC), proposed the term hepatoid adenocarcinoma due to the high AFP levels, ranging from 4730 to 700 000 ng/mL in serum. A serum AFP level higher than 200 ng/mL has been one of the screening criteria for HCC in international guidelines, and HCC may be diagnosed when liver tumors with high serum AFP are found among patients with liver cirrhosis[4,5]. Because of high serum AFP levels among patients with HAC, identification of tumor origin may be difficult, especially when liver tumors arising from HAC metastasis are initially found. Distinguishing between HAC and HCC is important, especially in areas with a high incidence of chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C and HCC.

HAC can originate from different organs such as the stomach[6], gallbladder[7], colon[8], lung[9] and urinary bladder[10], and the stomach is the most common origin of tumors in the literature. Finding the primary tumor origin of HAC is crucial, and prompt and adequate treatment may improve outcomes of patients. However, HCC with various extrahepatic metastases such as to the stomach has been reported[11], and determining the tumor origin may become a challenge for physicians, especially when clinicopathological findings of liver tumors are not typical for HCC. Pathological findings in immunohistochemical (IHC) stains may help in the differential diagnosis of HAC, and some specific IHC stains such as cytokeratin (CK)19, AFP, Hep-Par 1 and palate, lung, and nasal epithelium carcinoma-associated protein (PLUNC) have been used in the literature[12]. A systemic literature review regarding differential diagnosis of HAC by IHC stains is lacking, and the IHC presentations of HAC, HCC and common GAC (except HAC) are compared in this review.

The majority of HAC originates from the stomach, and the incidence of gastric HAC among GAC cases was reported to be 0.3%-1% in some recent articles[6,13,14]. The clinical features of gastric HAC are old age, aggressive clinical course, poor survival and frequent metastasis to the liver and lymph nodes, and data have suggested that HAC of the stomach has a poorer prognosis than common GAC[14]. Detection of tumors in the early stage, followed by surgical resection is still considered to be the only way to cure HAC. Because clinical presentations of HAC differ from those of common GAC, studies focusing on gastric HAC may be important in the future, and clinical characteristics may provide useful clues for further research. Moreover, a review of HAC originating from organs other than stomach is still lacking. To date, HAC has only been reported in case series or single case reports, so we aimed to review the clinicopathological characteristics of HAC to obtain a more complete picture of this rare form of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma.

All articles cited in the Medline/PubMed database from January 2001 to December 2011 were searched to identify relevant medical literature, and the search terms included “hepatoid adenocarcinoma”, “AFP-producing tumor”, “α fetoprotein-producing tumor” and “α fetoprotein-producing gastric cancer”. In addition, a manual search of all relevant articles was conducted. All studies with full text were included. The search limits were: (1) type of article: all types; (2) languages: English; (3) species: humans; (4) sexes: both male and female; (5) subsets: all types and fields; (6) ages: all ages; and (7) search field tags: titles. Studies without pathological confirmation of HAC or without clinical data were excluded.

A total of 98 articles were initially identified from the literature search. Among the 98 articles, 32 were excluded because the diagnosis was not confirmed as HAC, and 13 were excluded because the full text was not available. In total, 217 patients with HAC were included in our review. (All 53 reviewed articles are listed in Supplementary References online).

The clinical features of HAC cases are summarized in Table 1. Most HAC originated from the stomach (83.9%), and origins other than the stomach, including gallbladder (3.7%), uterus (3.2%), lung (2.3%) and urinary bladder (1.8%), were rare. Moreover, HAC originating from the esophagus and peritoneum was very rare (0.9%), and HACs of the rectum, transverse colon, testis, ovary, jejunum or ureter were only reported in single case report form (< 0.5%). The mean age of HAC patients was 63.0 ± 12.8 years, with a range of 21 to 100 years. Patients with HAC were usually male and the male-to-female ratio was 2.3:1. Most patients had elevated serum AFP (84.8%), with a range from less than 1.0 to 475 000 ng/mL.

| Number | Male (total), n | Female (total), n | Ratio M:F | Age (range), yr | Elevated serum AFP | Lymph node metastasis | Liver metastasis | Lung metastasis | Other metastasis | Operation | Chemotherapy | Median survival (range), mo | |

| Total | 217 (100) | 135 (194) | 59 (194) | 2.3:1 | 63 (21–100) | 78 (84.8) | 122 (57.5) | 94 (46.3) | 7 (3.4) | 16 (7.9) | 138 (80.2) | 49 (52.1) | 12 (1.2-66) |

| Stomach | 182 (83.9) | 121 (159) | 38 (159) | 3.2:1 | 63.3 (28–100) | 56 (87.5) | 115 (63.9) | 84 (48.8) | 5 (2.9) | 9 (5.2) | 107 (77.5) | 34 (50) | 13 (1.2-66) |

| Gallbladder | 8 (3.7) | 2 | 6 | 1:03 | 66.1 (55–76) | 3 (75) | 2 (28.6) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (100) | 2 (28.6) | 12 (5-20) |

| Uterus | 7 (3.2) | – | 7 | – | 69.4 (61–86) | 7 (100) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | 7 (100) | 5 (71.4) | 22 (12-36) |

| Lung | 5 (2.3) | 4 | 1 | 4:01 | 54.8 (49–68) | 2 (60) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | NA | 2 (40) | 5 (100) | 2 (50) | 15 (2-45) |

| Urinary bladder | 4 (1.8) | 4 | – | – | 70 (61–85) | 4 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 4 (100) | NA | 19 (12-26) |

| Esophagus | 2 (0.9) | 1 | 1 | 1:01 | 60 (44–76) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | N/A |

| Peritoneum | 2 (0.9) | 1 | 1 | 1:01 | 46.5 (21–72) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 6 |

| Retroperitoneum | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 | – | – | 47 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | N/A |

| Testis | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 | – | – | 36 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | 28 |

| Ovary | 1 (< 0.5) | – | 1 | – | 59 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | N/A |

| Jejunum | 1 (< 0.5) | – | 1 | – | 40 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | N/A |

| Transverse colon | 1 (< 0.5) | – | 1 | – | 59 | NA | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | N/A |

| Rectum | 1 (< 0.5) | – | 1 | – | 50 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA | N/A |

| Ureter | 1 (< 0.5) | – | 1 | – | 80 | NA | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | N/A |

When HAC was diagnosed, metastases from original organs were usually found. The most common sites of metastasis were lymph nodes (57.5%), followed by liver (46.3%) and lung (3.4%) metastasis. Liver and gastric tumors were often found simultaneously, and liver tumors could be detected before gastric tumors. As in common gastric cancer, surgical resection was the primary curative treatment in HAC. Most patients received surgical resection (80.2%), even when lymph node or distant metastases were found. In addition, about half of patients (52.1%) received adjuvant chemotherapy following surgical resection. In our literature review, survival data were not reported for all patients, but we were able to analyze data from 125 cases with various tumor origins. The median survival of all HAC patients was 12 mo, and 64 (51.2%) patients died within the first 12 mo.

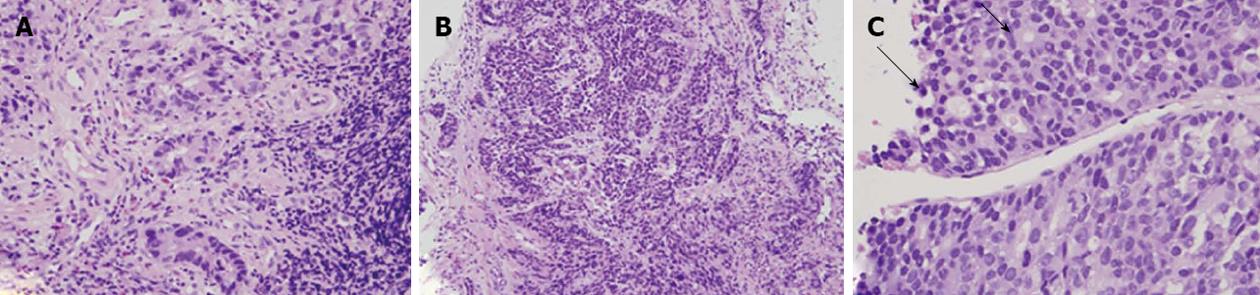

HAC usually showed morphologic similarity to HCC in histology, and polygonal tumor cells were found in hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stains. Polygonal tumor cells proliferating in both trabecular and intestinal-like structures could be found (Figure 1), but definite diagnosis of HAC was difficult only based on findings in histology. Further IHC stains were usually done for differential diagnosis.

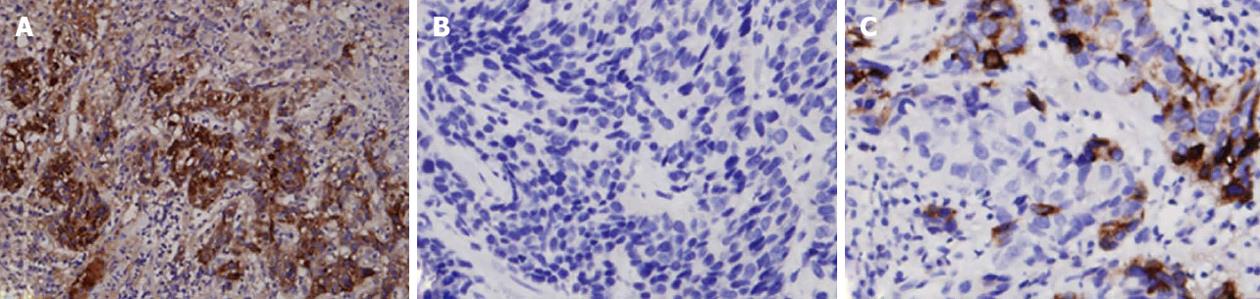

The major IHC presentations of HAC tumor tissues are depicted in Table 2. Positive AFP stains (Figure 2A) were found in the majority of HAC (91.6%), but positive Hep Par 1 stains were only found in some HAC patients (38.1%) (Figure 2B). In addition, positive carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) stains were found in most HAC patients (78.7%). Among epithelial markers, all HAC tumors were positive for both CK18 and CK19 stains (100%), and only a small proportion of HAC patients showed positive stains for CK20 (25%) and CK7 (15.4%). High proportions of HAC tumors were positive for pancytokeratin (AE1/AE3) stain (92.3%) and α1-antitrypsin (α1-AT) stain (91%), and 62.5% of HAC patients were positive for CD10 antigen. In addition, positive glypican 3 (GPC-3) staining (Figure 2C) was found in all HAC patients (100%).

| Number | AFP | Hep Par1 | CEA | CK18 | CK19 | CK20 | CK7 | AE1/AE3 | α1-AT | CD10 | GPC3 | |

| Total | 217 (100) | 177 (91.6) | 24 (38.1) | 37 (78.7) | 22 (100) | 27 (100) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (15.4) | 12 (92.3) | 10 (91) | 5 (62.5) | 10 (100) |

| Stomach | 182 (83.9) | 156 (90.6) | 12 (26.7) | 27 (75.0) | 17 (100) | 16 (100) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 7 (87.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) |

| Gallbladder | 8 (3.7) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (66.7) | 3 (75) | 1 (100) | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 3 (100) | NA |

| Uterus | 7 (3.2) | 6 (85.7) | NA | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (100) | NA |

| Lung | 5 (2.3) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (0) | NA | NA | 1 (100) | NA |

| Urinary bladder | 4 (1.8) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Esophagus | 2 (0.9) | 2 (100) | 1 (50) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (100) | NA | NA |

| Peritoneum | 2 (0.9) | 1 (50) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | NA | 0 (0) | NA | 1 (50) | NA | NA | NA |

| Retroperitoneum | 1 (< 0.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Testis | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ovary | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Jejunum | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Transverse colon | 1 (< 0.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rectum | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | NA | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ureter | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (100) | NA | NA | NA | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | NA | NA | 0 (0) | NA |

Although the stomach is the most common origin of HAC, the clinical presentation of HAC may vary greatly depending on the anatomic location of the tumor. Among gastric HAC cases, clinical symptoms were usually non-specific, such as fatigue, weight loss, nausea, poor appetite, emesis, diarrhea, epigastric distress, epigastric mass, abdominal pain or abdominal distension[15-17]. It is difficult to make a differential diagnosis from the clinical symptoms alone.

HAC is usually found in late middle-aged males, and elevated serum AFP is commonly noted among patients with HAC. Due to similar clinicopathological features, HAC may closely resemble and even be indistinguishable from HCC. Serum AFP has long been used for the screening and diagnosis of HCC, and high AFP in HAC may confuse physicians[4,5]. HAC may be incorrectly diagnosed as HCC, especially in endemic areas with a high incidence of HCC. AFP may be elevated in various conditions including HAC, so AFP is not suggested for diagnosis of HCC nowadays[18]. Diagnosis of HCC should be based on dynamic image studies (such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging) and/or liver tumor biopsy, and the typical dynamic image of HCC shows intense arterial uptake followed by “washout” of contrast in the venous and/or delayed phases[18]. Even in liver tumors with elevated AFP, secondary malignancies still should be considered especially when the presentations of imaging studies are atypical, and liver tumor biopsy is recommended for differential diagnosis. In addition, risk factors such as liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis B or chronic hepatitis C infection can usually be found among patients with HCC, but those risk factors may not be observed among patients with HAC. Once AFP-producing metastatic liver tumors are found, an intensive search for primary tumor origin should be initiated.

HAC is a very aggressive neoplasm with metastasis in a high proportion of patients at the time of diagnosis. Lymph nodes and the liver are the most common sites of metastasis. Once metastatic HAC is suspected, panendoscopy should be arranged because the stomach is the most common origin of HAC. HCC with metastasis to the stomach has been reported[11], and a clinical challenge of differentiating primary tumor origin arises when liver and gastric tumors are found simultaneously. Pathology markers, especially IHC stains, may provide clues to make a correct diagnosis. In addition, finding the tumor origin may be challenging when no tumor can be detected in the liver and/or stomach, so other organs such as the gallbladder, urogenital tract, lung and intestine should be carefully checked.

As a result of the high rate of metastasis and a disappointing response to chemotherapy in HAC, poor patient survival can be predicted. Data have suggested that HAC has a poorer prognosis than more common types of tumors[14], and more than half of patients died within the first 12 mo in our literature review. There has been no systemic therapy proven to be effective for HAC until now, but target therapy such as sorafenib is recommended as a standard treatment in HCC with extrahepatic metastasis to prolong patient survival[18].

Because HAC bears a striking morphologic similarity to HCC in histology and IHC stains, HCC could be mistakenly diagnosed when liver tumors are the only initial finding, especially in regions with a high incidence of HCC. However, HAC and HCC differ in histologic presentation, and specific findings suggesting HAC may provide important clues. Kodama et al[19] described two histologic types of HAC: one was the medullary type, characterized by polygonal cells arranged in a solid nest or sheets, with scattered large pleomorphic or multinucleated giant cells, and the other was well-differentiated papillary or tubular type with clear cytoplasm. However, two types of HAC sometimes coexist in a single tumor. If polygonal tumor cells proliferating in both trabecular and intestinal-like structures are found in HE staining, HAC should be considered (Figure 1).

HAC usually secretes some special chemomediators, so it could be characterized by some IHC stains (Table 2). As an AFP-producing tumor, HAC is commonly > 90% stained for AFP regardless of organ origin (Figure 2A). Although AFP is a characteristic stain for identifying HAC, it can also cause confusion in differentiating HAC from HCC. AFP, a well-known tumor marker of HCC, is usually secreted by HCC and gonadal tumors, and AFP can be positive in tissues of these tumors[20,21]. Hep Par 1, a highly specific marker of HCC, may help in the differential diagnosis between HAC and HCC (Figure 2B), but some HAC tumors can still present with positive staining. In addition, although a low percentage of gastric HAC was stained positive for Hep Par 1 (Table 2), high percentages of non-gastric HAC such as HAC of the gallbladder and urinary bladder were stained positive. However, due to the small case numbers of non-gastric HAC, large cohort studies are needed to confirm this finding. Moreover, other tumors such as adrenal cortical carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, colonic adenocarcinoma, lung carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma may be occasionally positive for Hep Par 1 stain[22].

The proportion of HAC with a positive CEA stain was high in both gastric (75%) and non-gastric HAC (75%-100%), but it can also be positive in HCC and other metastatic adenocarcinoma of the liver[23] arising from the gastrointestinal tract such as the colon[24,25], stomach[26] and pancreas[27]. Among epithelial markers, AE1/AE3, CK18 and CK19 are usually positive for HAC (92.3%, 100% and 100%, respectively), but the proportions of positive CK20 and CK7 stains are low (25% and 15.4%, respectively). CK7 and CK20 have diagnostic value in differentiating the tumors of unknown primary sites, and epithelial neoplasms with negative staining for CK7 and CK20 include adrenal cortical carcinoma, germ cell tumor, prostate carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, and HCC[28]. In the differential diagnosis between HAC and HCC for AFP-producing liver tumors, HAC is strongly suggested if AE1/AE3, CK18 and C19 stains show strong positive findings.

Regarding other IHC stains for HAC such as α1-AT, α1-antichemotrypsin, CD10, CDX2, MUC1, PLUNC and GPC-3 have been reported to be promising in the differential diagnosis of HAC[12]. For example, Sentani et al[29] reported that positive PLUNC staining was observed in all six gastric HAC, and PLUNC staining was also detected in both liver metastases. Furthermore, PLUNC staining was not observed in 52 cases of HCC, and it was a novel marker that might well distinguish HAC from HCC. However, case numbers in the literature were small (Table 2), and further studies to confirm sensitivity and specificity will be crucial.

In Table 3, we summarize and compare positive rates of commonly-used key IHC stains among HCC, HAC, and common GAC (except HAC) from our literature review[16,29-36] of the most common clinical malignancies needing differential diagnosis. Although the AFP stain can be positive in both HCC and HAC, it is overwhelmingly positive in HAC (91.6%) in our review. In other words, tumors with a negative AFP stain are rare in HAC, and they usually do not indicate HAC. Moreover, AFP staining is almost always negative in common GAC (0%-0.8%) in the literature, and it may be a useful tool to confirm HAC-type GAC. Similar to the AFP stain, the GPC-3 stain can be used in the differential diagnosis because of its low positive rate in common GAC but high positive rate in HAC (Figure 2C). However, although GPC-3 and AFP stains can be positive in both HCC and HAC, HCC with a negative AFP stain may be confirmed by GPC-3 staining. Hep Par 1 is another important stain with a high positive rate in HCC, but it can also be positive in some HAC (38.1%) in our review. The Hep Par 1 stain is usually negative in common GAC, and liver tumors with a negative Hep Par 1 stain suggest metastasis from other origins such as the stomach. Epithelial marker CK19 stain has an almost 100% positive rate in HAC, and it is also frequently positive in common GAC. However, the positive rate of CK19 in HCC is very low, and HCC is usually not suggested with a positive CK19 stain in liver tumors. In summary, HAC is a special type of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with pathological presentation mimicking HCC, and HAC should be suspected once polygonal tumor cells proliferating in both trabecular and intestinal-like structures are found in HE staining. There is no single IHC stain that can completely differentiate HAC from HCC, and a panel of IHC stains, such as CK19, PLUNC, Hap-Par 1 and CEA, with detailed clinical history and endoscopic findings are essential for definitive diagnosis.

HAC is a rare but important special type of extrahepatic adenocarcinoma with clinicopathological presentation mimicking HCC, and prompt and correct diagnosis can be a challenge, especially in endemic areas with a high incidence of HCC. A late middle-aged male with high serum AFP and atypical image findings of HCC should raise the suspicion of HAC, and characteristic pathological IHC stains can help in differential diagnosis. Novel IHC markers may be useful to clearly differentiate HAC from HCC. Once metastatic HAC is diagnosed, a search for the primary tumor origin should be initiated for adequate treatment. The majority of HAC arise from the stomach, so panendoscopy should be arranged first.

P- Reviewers Currò G, Zhang JZ, Kobayashi T S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Bourreille J, Metayer P, Sauger F, Matray F, Fondimare A. [Existence of alpha feto protein during gastric-origin secondary cancer of the liver]. Presse Med. 1970;78:1277-1278. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ishikura H, Fukasawa Y, Ogasawara K, Natori T, Tsukada Y, Aizawa M. An AFP-producing gastric carcinoma with features of hepatic differentiation. A case report. Cancer. 1985;56:840-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ishikura H, Kirimoto K, Shamoto M, Miyamoto Y, Yamagiwa H, Itoh T, Aizawa M. Hepatoid adenocarcinomas of the stomach. An analysis of seven cases. Cancer. 1986;58:119-126. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4333] [Cited by in RCA: 4508] [Article Influence: 225.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3252] [Cited by in RCA: 3244] [Article Influence: 135.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kumashiro Y, Yao T, Aishima S, Hirahashi M, Nishiyama K, Yamada T, Takayanagi R, Tsuneyoshi M. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach: histogenesis and progression in association with intestinal phenotype. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gakiopoulou H, Givalos N, Liapis G, Agrogiannis G, Patsouris E, Delladetsima I. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3358-3362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu Q, Bannan M, Melamed J, Witkin GB, Nonaka D. Two cases of hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the intestine in association with inflammatory bowel disease. Histopathology. 2007;51:123-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hayashi Y, Takanashi Y, Ohsawa H, Ishii H, Nakatani Y. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma in the lung. Lung Cancer. 2002;38:211-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lopez-Beltran A, Luque RJ, Quintero A, Requena MJ, Montironi R. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch. 2003;442:381-387. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sano T, Izuishi K, Takebayashi R, Akamoto S, Kakinoki K, Okano K, Masaki T, Suzuki Y. Surgical approach for extrahepatic metastasis of HCC in the abdominal cavity. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:2067-2070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Metzgeroth G, Ströbel P, Baumbusch T, Reiter A, Hastka J. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma - review of the literature illustrated by a rare case originating in the peritoneal cavity. Onkologie. 2010;33:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nagai E, Ueyama T, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Cancer. 1993;72:1827-1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu X, Cheng Y, Sheng W, Lu H, Xu X, Xu Y, Long Z, Zhu H, Wang Y. Analysis of clinicopathologic features and prognostic factors in hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1465-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Inagawa S, Shimazaki J, Hori M, Yoshimi F, Adachi S, Kawamoto T, Fukao K, Itabashi M. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2001;4:43-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Terracciano LM, Glatz K, Mhawech P, Vasei M, Lehmann FS, Vecchione R, Tornillo L. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and molecular study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1302-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Caruso RA, Basile F, Fedele F, Zuccalà V, Crisafulli C, Fracassi MG, Quattrocchi E, Venuti A, Fabiano V. Gastric hepatoid adenocarcinoma with autophagy-related necrosis-like tumor cell death: report of a case. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6573] [Article Influence: 469.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Kodama T, Kameya T, Hirota T, Shimosato Y, Ohkura H, Mukojima T, Kitaoka H. Production of alpha-fetoprotein, normal serum proteins, and human chorionic gonadotropin in stomach cancer: histologic and immunohistochemical analyses of 35 cases. Cancer. 1981;48:1647-1655. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Li P, Wang SS, Liu H, Li N, McNutt MA, Li G, Ding HG. Elevated serum alpha fetoprotein levels promote pathological progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4563-4571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hammad A, Jasnosz KM, Olson PR. Expression of alpha-fetoprotein by ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. Case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:1075-1079. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Fan Z, van de Rijn M, Montgomery K, Rouse RV. Hep par 1 antibody stain for the differential diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: 676 tumors tested using tissue microarrays and conventional tissue sections. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Porcell AI, De Young BR, Proca DM, Frankel WL. Immunohistochemical analysis of hepatocellular and adenocarcinoma in the liver: MOC31 compares favorably with other putative markers. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:773-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Naghibalhossaini F, Ebadi P. Evidence for CEA release from human colon cancer cells by an endogenous GPI-PLD enzyme. Cancer Lett. 2006;234:158-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bombski G, Gasiorowska A, Orszulak-Michalak D, Neneman B, Kotynia J, Strzelczyk J, Janiak A, Malecka-Panas E. Elevated plasma gastrin, CEA, and CA 19-9 levels decrease after colorectal cancer resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:148-152. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Pectasides D, Mylonakis A, Kostopoulou M, Papadopoulou M, Triantafillis D, Varthalitis J, Dimitriades M, Athanassiou A. CEA, CA 19-9, and CA-50 in monitoring gastric carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20:348-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brand RE, Nolen BM, Zeh HJ, Allen PJ, Eloubeidi MA, Goldberg M, Elton E, Arnoletti JP, Christein JD, Vickers SM. Serum biomarker panels for the detection of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:805-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chu P, Wu E, Weiss LM. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:962-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 641] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sentani K, Oue N, Sakamoto N, Arihiro K, Aoyagi K, Sasaki H, Yasui W. Gene expression profiling with microarray and SAGE identifies PLUNC as a marker for hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:464-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yamauchi N, Watanabe A, Hishinuma M, Ohashi K, Midorikawa Y, Morishita Y, Niki T, Shibahara J, Mori M, Makuuchi M. The glypican 3 oncofetal protein is a promising diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1591-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kakar S, Muir T, Murphy LM, Lloyd RV, Burgart LJ. Immunoreactivity of Hep Par 1 in hepatic and extrahepatic tumors and its correlation with albumin in situ hybridization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:361-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lugli A, Tornillo L, Mirlacher M, Bundi M, Sauter G, Terracciano LM. Hepatocyte paraffin 1 expression in human normal and neoplastic tissues: tissue microarray analysis on 3,940 tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:721-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lee MJ, Lee HS, Kim WH, Choi Y, Yang M. Expression of mucins and cytokeratins in primary carcinomas of the digestive system. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:403-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lau SK, Prakash S, Geller SA, Alsabeh R. Comparative immunohistochemical profile of hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:1175-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hishinuma M, Ohashi KI, Yamauchi N, Kashima T, Uozaki H, Ota S, Kodama T, Aburatani H, Fukayama M. Hepatocellular oncofetal protein, glypican 3 is a sensitive marker for alpha-fetoprotein-producing gastric carcinoma. Histopathology. 2006;49:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kim MA, Lee HS, Yang HK, Kim WH. Cytokeratin expression profile in gastric carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:576-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |