INTRODUCTION

Performing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) using a conventional duodenoscope in patients with bowel reconstruction due to a previous abdominal surgery is challenging because it is frequently impossible to reach the papilla or the hepatico/choledochojejunal and pancreaticojejunal anastomosis owing to the insufficient scope length and unusual postsurgical conditions such as intestinal adhesions and anastomosis angulation. However, the use of a double-balloon enteroscope (DBE), which was originally developed for the management of small bowel diseases[1], has been shown to make it more feasible to perform ERCP in patients with bowel reconstruction[2-7]. Recently, ERCP using a DBE (DB-ERCP) is now widely accepted. In particular, a short DBE, which has a 2.8-mm working channel and 152-cm working length, is useful for ERCP because of its good rotational and straightening ability and the availability of various conventional ERCP accessories through the working channel. ERCP using a short DBE was reported to be useful and safe for diagnostic and therapeutic interventions such as sphincterotomy, stone extraction, and stent placement[8-11]. In this paper, we report a case of a post-surgical patient diagnosed as having intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma via ERCP with a short DBE. We aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of successfully achieving access to the biliary duct by pre-cutting under a DBE and obtaining the pathological diagnosis by tissue sampling via DB-ERCP.

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old man, who had undergone partial gastrectomy with gastrojejunostomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction for gastric carcinoma five years before, presented to another hospital to evaluate a mass lesion in hepatic segment VIII. A fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan revealed a pathological uptake pattern with a maximum standardized uptake value of 5.6 in the mass, suggestive of a malignant tumor. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle biopsy was performed to obtain a pathological diagnosis of the mass. However, the biopsy finding revealed no sign of malignancy. In addition, the patient developed biliary peritonitis after the liver biopsy and therefore required hospitalization and conservative treatment for approximately 1 mo. One month after discharge from the hospital, an ultrasound image revealed the mass lesion remained constant in size; however biliary stricture with upstream dilatation, which appeared to result from the mass lesion, was noted on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Hence, he was referred to our hospital to undergo evaluation for malignancy by tissue sampling from the biliary stricture.

On admission, the patient was asymptomatic. The physical examination results were unremarkable. He had no history of alcohol abuse. The serum examination results indicated that the levels of the tumor markers and transaminase in the liver were within normal limits. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed a slightly hyperintense lesion around the dilated intrahepatic duct in segment VIII (Figure 1A). On MRCP, a focal biliary stricture with upstream dilatation in the branch arising from the right anterior duct was observed (Figure 1B). The patient underwent ERCP with a short DBE (EC-450BI5; Fujifilm, Osaka, Japan) in the prone position with carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflations. At first, a short DBE was carefully inserted into the blind loop and reached the papilla. Subsequently, standard biliary cannulation using a straight cannula (PR-10Q; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was attempted after the papilla was moved to the lower endoscopic field of view by keeping the overtube balloon inflated and rotating the enteroscope (Figure 2A), as described in a previous report[8]. However, we were unable to obtain cholangiography, but only pancreatography. Therefore, a 0.025-inch guide wire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the main pancreatic duct (Figure 3A), and the pre-cut technique was carried out with a wire-guided sphincterotome (Autotome RX, Boston Scientific, Japan). The incision was started toward the biliary direction and was stopped at the lower one-third of the ampullary mound (Figure 2B). After the incision, the orifice of the biliary duct became visible (Figure 2C), and selective biliary cannulation with a straight cannula was performed successfully (Figure 3B). After contrast enhancement of the biliary duct, a focal stricture in the branch of the right intrahepatic duct was identified under radiographic guidance (Figure 3C). A guide wire followed by a cannula was successfully passed through the stricture after several negotiations (Figure 3D). Subsequently, tissue sampling for cytological examination was performed at the level of the stricture using a brush device (Cytomax II DLB 35-1.5; Cook, Osaka, Japan) introduced by a guide wire (Figure 3E). Finally, the nasobiliary drainage tube was placed at the distal side to collect the bile for cytological examination (Figure 3F). The day after the ERCP, a slight increase in the serum amylase level was observed, but the patient did not complain of abdominal pain. The result of the cytological examinations of the sample obtained by the brush and nasobiliary drainage tube was positive for malignancy. On the basis of the cytological finding, the patient underwent segmentectomy of the left lobe. The final pathological report indicated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

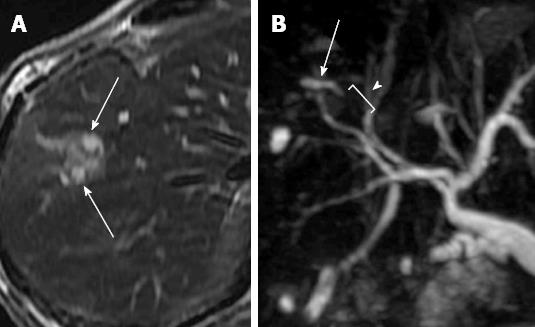

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging.

A: The T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging shows a hyperintense lesion along the dilated intrahepatic duct (arrows); B: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography shows a stricture of biliary duct (arrow) with the upstream dilatation (arrowhead).

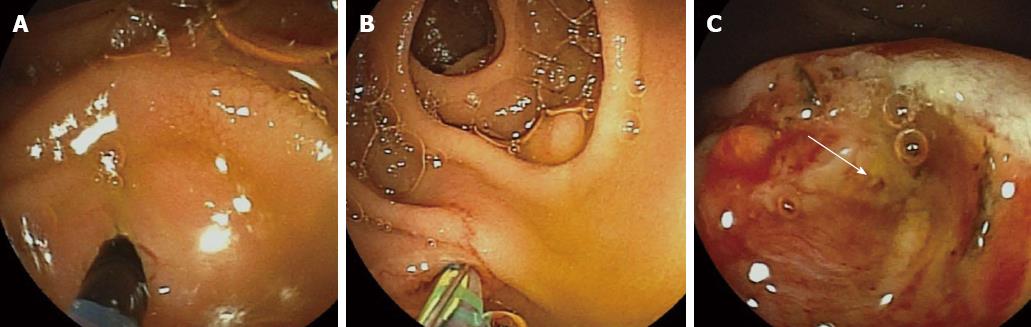

Figure 2 Endoscopic images during cannulation and transpancreatic sphincterotomy.

A: Selective biliary cannulation was attempted in the position of the papilla moved to the lower endoscopic field of view; B: The wire-guided transpancreatic sphincterotomy was performed toward the biliary direction; C: The bile duct orifice was exposed after the transpancreatic sphincterotomy (arrow).

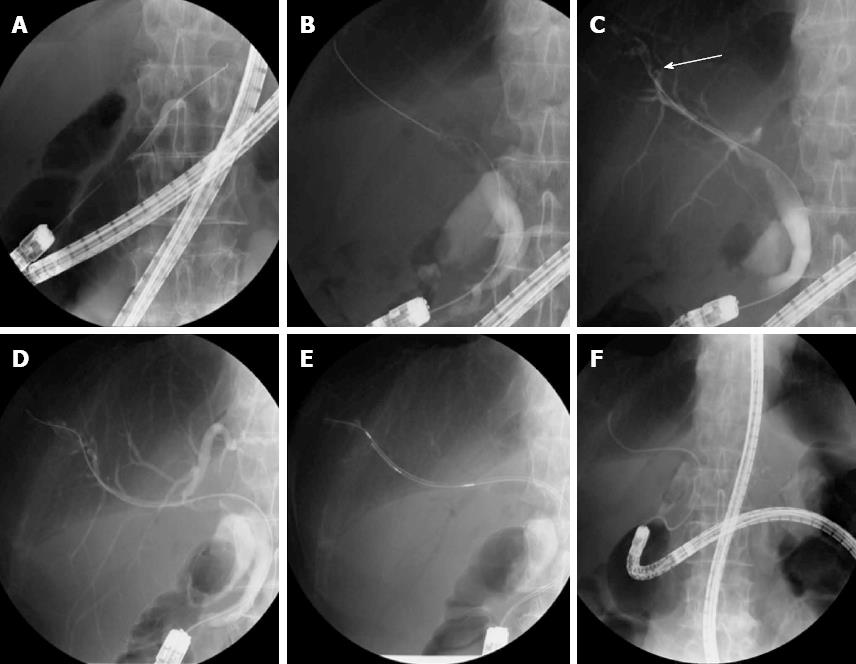

Figure 3 Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

A: A guide wire was inserted deeply into the main pancreatic duct to perform the pre-cutting; B: After the pre-cutting, selective biliary cannulation was achieved; C: Cholangiography revealed a focal stricture in the branch of the right intrahepatic duct (arrow); D: A guide wire was passed through the biliary stricture; E: The brush cytological examination was carried out at the stricture; F: The placement of nasobiliary drainage tube was performed to collect the bile for cytology.

DISCUSSION

With the advent of DBEs, the endoscopic management of pancreaticobiliary diseases has become more feasible in patients with previous gastrointestinal surgery such as Billroth II gastrojejunostomy, Roux-en-Y reconstruction, and Whipple’s resection[2-6]. Accordingly, in these years, the number of published reports on the utility of DB-ERCP has been increasing. In most of these previous reports, a standard DBE (EN-450T5; Fujifilm)[2-6] and a single-balloon enteroscope[7] were used. However these enteroscopes have a limitation with regard to the availability of its accessories because of its 200-cm working length. In contrast, a short DBE has a 2.8-mm working channel and 152-cm working length, for which various diagnostic and therapeutic accessories used in conventional ERCP, including sphincterotome, balloon catheter, basket, biopsy forceps, brush, intraductal ultrasonic probe and biliary stent, are available without modification[8-11]. The use of a short DBE appears to not only widen the parameters of the procedures which we can perform in DB-ERCP, but also increase the success rate of the procedure owing to its good maneuverability. In fact, with a short DBE, we reported higher success rates in deep insertion [100/103 (97%)], cholangiography [98/100 (98%)], and therapeutic interventions [98/98 (100%)], compared with the previous reports[8].

Deep cannulation to the biliary duct is the most important step for successful ERCP. The failure rate for cannulation of the naive papilla in conventional ERCP is reported to be up to 10% of the ERCP procedures[12,13]. In general, this rate in DB-ERCP might be even higher because of the difficult location of the papilla and the instability of the manipulation of the enteroscope and cannula. In the case of a difficult biliary cannulation in conventional ERCP, the pre-cut techniques have been used as a widely accepted option to facilitate the biliary access[14,15]. The pre-cut techniques include needle knife sphincterotomy and wire assisted transpancreatic sphincterotomy. In contrast with conventional duodenoscopy, a DBE is forward viewing and has no elevator function, making the pre-cutting technically more challenging. From our experience, we recommend wire-guided transpancreatic sphincterotomy in performing the pre-cutting under a DBE, because the direction, depth, and length of incision are easier to control, compared with needle knife papillotomy performed freehand.

Although intrahepatic stricture frequently results from malignant disease such as cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, it is important to confirm the malignant cells histopathologically by the tissue sampling method, because an accurate diagnosis is crucial for the choice of an appropriate therapeutic strategy. In general, percutaneous needle biopsy is accepted for histological diagnosis when the mass causing the intrahepatic stricture can be detected on ultrasonography. However, the potential disadvantage of this technique is that complications such as pneumothorax, hemorrhage, biliary leakage, biliary peritonitis, and tumor seeding can occur[16,17]. In contrast, the transpapillary tissue sampling methods during ERCP include brush cytological examination, bile cytological examination, and biopsy. In particular, brush cytological examination is commonly used because it is relatively simple and safe. Although the specificity of this method for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma is almost 100%, the sensitivity is by no means satisfactory, ranging from 44% to 81%[18]. In our institution, when brushing is performed, bile cytological examination is also performed via a nasobiliary drainage tube placed subsequently after brushing. We believe that such a combination of specimen collection methods enhances the cancer detection rate.

In conclusion, the short DBE allowed us to perform all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures accepted in conventional ERCP in patients with surgically altered anatomies.