Published online Jul 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4413

Revised: March 15, 2013

Accepted: April 27, 2013

Published online: July 21, 2013

Processing time: 194 Days and 16.3 Hours

Crohn’s disease (CD), a variant of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, frequently affects the terminal ileum and coecal region. The clinical symptoms are often subtle and depend on the inflammatory activity of disease. In women of child-bearing age, florid intestinal endometriosis can simulate CD. Moreover, current pathophysiological concepts include intestinal endometriosis as a putative founder lesion for consecutive CD establishment. The report summarizes clinical and histomorphological data of a 35-year-old woman with the rare coincidence of florid intestinal endometriosis and CD both affecting the terminal ileum. The patient was suffering over 10 years from strong abdominal disorders including constipation, diarrhea, weight loss, and diffuse abdominal pain. In magnetic resonance imaging-Sellink, strong inflammation and intestinal obstruction of the terminal ileum were found. The laparoscopy revealed further evidence for existence of an inflammatory disease like CD, but brownish spots on the peritoneum were found indicative for endometriosis. Surgical resection of the terminal ileum and the coecal segment was performed followed by histopathological investigations. In transmural sections of the terminal ileum, histomorphological features of florid endometriosis intermingled with florid CD was found. The diagnostic findings were substantiated with a panel of immunohistological stainings. In conclusion, the findings demonstrate that florid endometriosis persists in florid CD lesions and the putative link between intestinal endometriosis and CD is more complex than previously assumed.

Core tip: A 35-year-old woman with the rare constellation of a strong mixture of florid intestinal endometriosis and Crohn’s disease in the terminal ileum is presented. Our findings suggest that there exist a putative link between the pathogenesis of both entities, which is more complex than previously assumed.

- Citation: Kaemmerer E, Westerkamp M, Kasperk R, Niepmann G, Scherer A, Gassler N. Coincidence of active Crohn's disease and florid endometriosis in the terminal ileum: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(27): 4413-4417

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i27/4413.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4413

Crohn’s disease (CD), a variant of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, is of unknown aetiology. Changes of the intestinal mucosal barrier are considered to play a role in the pathogenesis. Its incidence peaks in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life. CD most commonly affects the terminal ileum and coecal region, but may be found in any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Clinical signs and symptoms of CD are often subtle and depend on the location and severity of the gastrointestinal involvement as well as inflammatory activity. CD related symptoms may include abdominal pain, severe diarrhea (sometimes with blood), weight loss and even malnutrition[1]. Growth retardation may occur in pediatric patients[2]. Other important symptoms which could be associated with CD are intestinal obstruction, perirectal or perianal abscesses, perforation and fistulas[3]. Because a plethora of non characteristic symptoms can be found in CD, a large list of differential diagnosis exists.

When the terminal ileum is affected in a woman of child-bearing age, endometriosis should be included in the differential diagnosis because this entity can simulate CD not only clinically[4]. Endometriosis is characterized by proliferation of endometrial tissue at extrauterine sites including ovaries, peritoneum and the intestinal tract. At present, the etiology of endometriosis is not fully understood. Its incidence peaks in the 3rd decade of life. About 5%-10% of women in menstruating age are affected[5]. Importantly, endometriosis affecting the intestinal tract is found in 3%-37% of women. Rectosigmoid, proximal/middle colon, appendix, and ileum are the most commonly affected sites. Similar to CD, the symptoms in intestinal endometriosis are not characteristic and include abdominal pain, (bloody) diarrhea, constipation, and segmental inflammation[6].

We present here the rare case of coincidence of active CD and florid endometriosis both affecting the terminal ileum of a 35-year-old woman.

The patient, a 35-year-old woman, was admitted to our surgical department first in August 2012. She was suffering from strong abdominal disorders over 10 years with constipation, diarrhea, and diffuse abdominal pain resulting in impaired nutrition and weight loss. The abdominal disorders were not related to the period, and dysmenorrhea was not given. Manifestation of CD was suggested years ago but not further substantiated or medical treated. The patient had a 12-year-old daughter, negative family history for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases and cancer. The last coloscopy in July 2012 showed a swelling of the intestinal mucosa of the ileocecal region. In biopsies, uncharacteristic moderate inflammation was found.

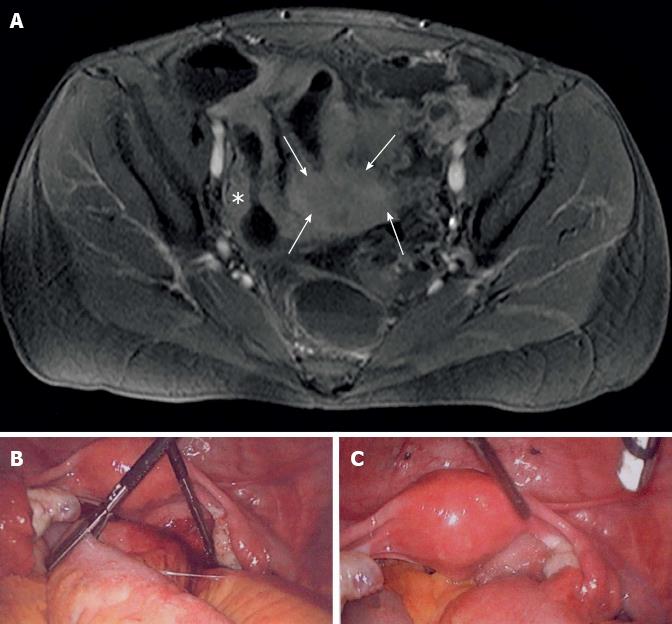

In order to clarify the obscure abdominal disorder, magnetic resonance imaging-Sellink was performed. Using this technique, strong inflammation and intestinal obstruction affecting a long part of the distal small intestinal bowel, Bauhin’s valve, and coecum were found. In the lower pelvis, an uncharacteristic mass of tissue involving the bowel was additionally visible (Figure 1A). All results so far were unspecific but lead us to the estimated diagnosis of CD with severe intestinal obstruction and tumour like transformation. So we decided to perform laparoscopic intervention.

The laparoscopy revealed an inflammatory disease affecting the distal small bowel with strong tumour like adhesion to the pelvis, but inconspicuous uterus and adnexa (Figure 1B). In addition, some brownish spots on the pelvis and bladder peritoneum were found that macroscopically appeared as endometriosis (Figure 1C). By laparoscopical intervention, it was impossible to free the intestinal segment. Consequently, a longitudinal laparotomie was performed. The tumour like inflamed small intestinal segment and the ileocoecal portion were resected. Both ureters were not affected by the inflammation. Following a gynaecological council and the fact that intra-operative frozen sections of the tumour-like lesion in the spatium rectovaginale did not demonstrate endometriosis, the inflamed mass in the lower pelvis was not resected. It was taken into account that resection of the tumour-like lesion, probably an additional manifestation of CD, was impossible without anterior rectum resection.

In the follow-up, the patient recovered quickly with one day observation on the intensive care unit. With the fast track concept the patient was quickly activated and within 4 d nutrition was increased to normal. Intestinal anastomosis (ileo-ascendostomia) and all wounds healed primarily and without any complications. Using anti-inflammatory and antibiotic therapies, the inflamed mass in the lower pelvis was diminished. The patient is now incorporated in our follow-up care system and will be systematically re-evaluated.

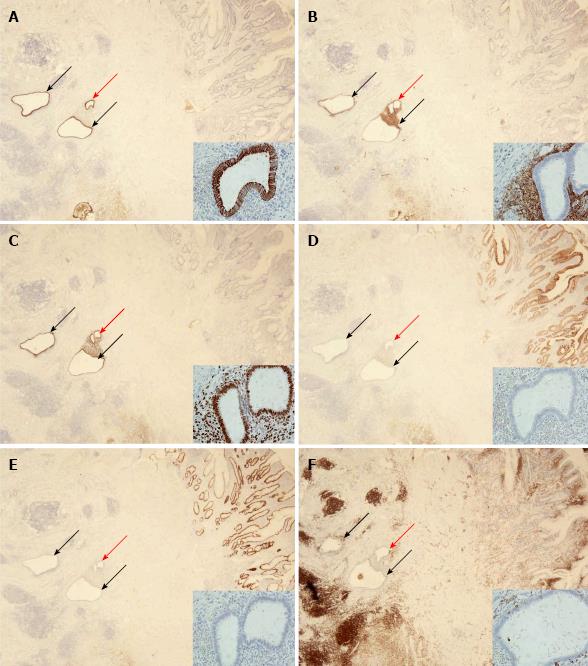

The resected specimen was fixed in 10% formaldehyde for about 24 h followed by tissue preparation. Representative tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Tissue sections were stained with HE, sometimes with PAS. In addition, an extensive panel of immunohistochemical routine stains were performed using the DAKO Autostainer Link 48 system and commercially available primary antibodies and detection systems (all DAKO Deutschland, Hamburg, Germany). The primary antibodies included CD45 (dilution 1:2000), CD10 (dilution 1:50), K7 (dilution 1:1000), K20 (dilution 1:200), CDX2 (dilution 1:50), and progesterone receptor (dilution 1:350). With the exception of CDX2, all antigens were uncovered with pre-treatment at pH 6.1 as recommended by the supplier. In order to detect the CDX2 antigen, tissues slides were pre-treated at pH 9.0.

The surgical specimen includes a 32 cm small intestine with a 6 cm coecal segment, 4.5 cm appendix, and 1.5 cm mesenteric fatty tissue. High grade stenosis of the small intestine with wall thickening, several aphthous lesions, and destruction of Bauhin’s valve were found. Macro-sections revealed diffuse fibrosis of the intestinal wall and aspects of serositis.

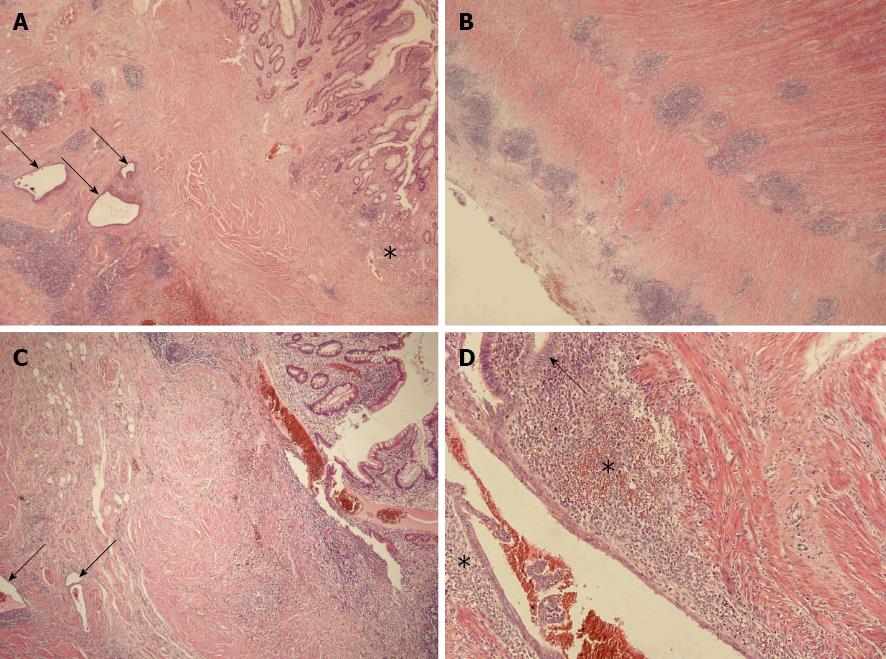

Tissue sections of the small intestinal bowel wall demonstrated a mixture of two histomorphological patterns (Figure 2). At first, a multifocal erosive-ulcerative, aphthous process with transmural lymphoid aggregates and chronic inflammation of serosal tissue layers was found. Moreover, pyloric gland metaplasia was frequently established in the mucosa layer. Despite missing granulomas, the morphological aspects were diagnostic for manifestation of CD (activity score III). In addition to CD, a second histomorphological pattern was found. Several areas with gland forming epithelial cells adjacent to a cell rich matrix were distributed within the CD lesions, reflecting florid endometriosis in CD. The endometriosis glands were sometimes accompanied by few siderophages. The endometriosis was distributes throughout the small intestinal wall and preferentially found in the inner layer of the tunica muscularis. The basic histomorphological findings were further characterized by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3).

CD is an important variant of inflammatory bowel disease and it is assumed as a disorder with polyetiological background. Modern pathophysiological concepts include intestinal endometriosis as a putative risk factor to promote development of inflammatory bowel disease in particular CD. Following results from a Danish long-term study group in 2011 it is suggested that likelihood of CD in women with endometriosis is higher than in the control population[7]. In detail, the data reflects the situation that endometriosis gives a basis for the manifestation of CD and possible autoimmune triggered diseases even in the long term after the diagnosis of endometriosis. In this study the risk of CD manifestation was highest among women diagnosed with endometriosis below the age of 25 years. The possible link between both diseases is substantiated by the following points: (1) both are inflammatory diseases; (2) the CD is preferentially found in women; and (3) both diseases are characterized by intermittent appearance. Common immunological features or an impact of endometriosis treatment with oral contraceptives on risk of CD must be also discussed as possible links[8,9]. In view with these studies, occurrence of florid CD mixed-up with florid small intestinal endometriosis as presented here is a rare constellation.

In contrast to CD, terminal ileal involvement from endometriosis is uncommon and occurs only in 1%-7% of all patients with intestinal endometriosis[10]. Patients with intestinal endometriosis of the terminal ileum are usually young nulliparous women who present with intermittent or persistent abdominal pain and possible obstruction. These features apply only partially to the case presented here.

The data presented here have some parallels to a Belgian case series[11]. In the Belgian study, clinical and histological findings from eight females with simultaneous histological diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis and CD were addressed. However, the strong mixture of active CD and florid intestinal endometrial deposits in terminal ileum tissues was not recorded. From this point of view, our case clearly demonstrates that both florid entities can mixed-up in the terminal ileum.

It could be speculated from our findings and the Belgian study that the sequence of events in manifestation of CD after endometriosis is high variable including persistence of intestinal endometriosis[11]. In addition, the strong mixture of the two histological patterns as demonstrated here raises the possibility that intestinal CD lesions are secondary involved by intestinal endometriosis. This hypothesis could be further substantiated by anamnestic data of our patient, where CD was assumed years ago, but (intestinal) endometriosis was never assumed.

Non-invasive diagnostic separation of intestinal endometriosis and CD raises several problems. This is due to the fact that both diseases may affect the bowel and may cause abdominal pain. They are associated with inflammation, tissue induration, wall thickening and structuring. In addition, both diseases have a known fairly long delay from onset to diagnosis. Immunological features of endometriosis, including serological alterations as raised cytokine levels, decreased cell apoptosis, B- and T-cell abnormalities are comparable to those seen in CD[12].

Finally, it has to be stressed that intestinal endometriosis and CD are important differential diagnoses in view of therapeutic procedures. Pharmaceutical therapies are completely different between intestinal endometriosis and CD. Concerning surgical intervention it should be stressed that intestinal segment resection could be therapeutic in intestinal endometriosis, whereas in CD patients resections are always symptomatic treatment.

Here we demonstrate the rare constellation of a strong mixture of florid intestinal endometriosis and CD in the terminal ileum of a 35-year-old patient. Our findings suggest that the putative link between the pathogenesis of both entities is more complex than previously assumed.

The authors are grateful to Petra Akens for proofreading the manuscript.

P- Reviewers Rivlin ME, VavilisD S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Hendrickson BA, Gokhale R, Cho JH. Clinical aspects and pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:79-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 396] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kirschner BS. Permanent growth failure in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:368-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lewis RT, Maron DJ. Anorectal Crohn’s disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:83-97, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cappell MS, Friedman D, Mikhail N. Endometriosis of the terminal ileum simulating the clinical, roentgenographic, and surgical findings in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1057-1062. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Okeke TC, Ikeako LC, Ezenyeaku CC. Endometriosis. Niger J Med. 2011;20:191-199. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bergqvist A. Different types of extragenital endometriosis: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1993;7:207-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jess T, Frisch M, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM. Increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women with endometriosis: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut. 2012;61:1279-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Ananthakrishnan AN, Richter JM, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:1153-1159. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental triggers for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | De Ceglie A, Bilardi C, Blanchi S, Picasso M, Di Muzio M, Trimarchi A, Conio M. Acute small bowel obstruction caused by endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3430-3434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Craninx M, D’Haens G, Cokelaere K, Baert F, Penninckx F, D’Hoore A, Ectors N, Rutgeerts P, Geboes K. Crohn’s disease and intestinal endometriosis: an intriguing co-existence. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nothnick WB. Treating endometriosis as an autoimmune disease. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |