Published online Jul 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4344

Revised: February 12, 2013

Accepted: March 21, 2013

Published online: July 21, 2013

Processing time: 208 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate adherence rates in tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-inhibitors in Crohn’s disease (CD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by systematic review of medical literature.

METHODS: A structured search of PubMed between 2001 and 2011 was conducted to identify publications that assessed treatment with TNF-α inhibitors providing data about adherence in CD and RA. Therapeutic agents of interest where adalimumab, infliximab and etanercept, since these are most commonly used for both diseases. Studies assessing only drug survival or continuation rates were excluded. Data describing adherence with TNF-α inhibitors were extracted for each selected study. Given the large variation between definitions of measurement of adherence, the definitions as used by the authors where used in our calculations. Data were tabulated and also presented descriptively. Sample size-weighted pooled proportions of patients adherent to therapy and their 95%CI were calculated. To compare adherence between infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept, the adherence rates where graphed alongside two axes. Possible determinants of adherence were extracted from the selected studies and tabulated using the presented OR.

RESULTS: Three studies on CD and three on RA were identified, involving a total of 8147 patients (953 CD and 7194 RA). We identified considerable variation in the definitions and methodologies of measuring adherence between studies. The calculated overall sample size-weighted pooled proportion for adherence to TNF-α inhibitors in CD was 70% (95%CI: 67%-73%) and 59% in RA (95%CI: 58%-60%). In CD the adherence rate for infliximab (72%) was highercompared to adalimumab (55%), with a relative risk of 1.61 (95%CI: 1.27-2.03), whereas in RA adherence for adalimumab (67%) was higher compared to both infliximab (48%) and etanercept (59%), with a relative risk of 1.41 (95%CI: 1.3-1.52) and 1.13 (95%CI: 1.10-1.18) respectively. In comparative studies in RA adherence to infliximab was better than etanercept and etanercept did better than adalimumab. In three studies, the most consistent factor associated with lower adherence was female gender. Results for age, immunomodulator use and prior TNF-α inhibitors use were conflicting.

CONCLUSION: One-third of both CD and RA patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors are non-adherent. Female gender was consistently identified as a negative determinant of adherence.

Core tip: This study assessed adherence with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors in Crohn’s disease (CD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) by systematic review. We found only two-third of the patients with CD and RA receiving TNF-α inhibitors adherent to therapy. Definitions of measurement of adherence varied widely between studies and there is no clarity on what levels of adherence are required for optimal results of therapy. Future research on adherence should focus on therapy outcome, by using uniform definitions of adherence.

- Citation: Fidder HH, Singendonk MM, van der Have M, Oldenburg B, van Oijen MG. Low rates of adherence for tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors in Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(27): 4344-4350

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i27/4344.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4344

Crohn’s disease (CD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are chronic inflammatory conditions characterized by episodes of remission and flare-ups that have a major impact on the patient’s physical, emotional and social well-being. The management of these diseases has been profoundly modified by the introduction of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors, i.e., infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept (only in RA), and these agents have become an integral part of the therapeutic arsenal. In RA TNF-α inhibitors have shown to rapidly improve symptoms, retard radiographic disease progression and improve functional status and health-related quality of life[1]. Also in CD TNF-α inhibitors are highly efficacious for induction and maintenance therapy and reduce rates of hospitalization and surgery[2].

Clinical effectiveness of TNF-α inhibitors is dependent on adequate adherence, and failure to stick to the prescribed drug regimen contributes to failure of treatment and disease recurrence. For both RA and CD, good adherence is associated with more effective treatment, including limited loss of response[3,4]. Fernández-Nebro et al[4] reported that in CD the probability of premature failure of TNF-α inhibitors was 61% less in patients with good adherence.

For patients with inflammatory bowel disease, reported non-adherence rates for oral medication range in most studies between 30%-45%[5]. Low adherence has an impact on healthcare budgets by increasing number of treatment failures, subsequent diagnostic procedures and unnecessary change of therapy. A Cochrane review on adherence concluded that improving medicine intake may have a far greater impact on clinical outcomes than an improvement in treatments[6]. In line with this statement Kane et al[7] pointed out that all-cause and CD-related medical costs were 81% and 94% higher, respectively, for non-adherent patients in comparison to adherent patients.

Although it has been 15 years since TNF-α inhibitors were introduced for the treatment of CD and RA, our understanding of patient’s compliance to TNF-α inhibitors is minimal and reported rates of adherence vary widely, depending on the definition of adherence. In order to assess the adherence rates for TNF-α inhibitors in CD and RA, we systematically reviewed literature and performed meta-analysis.

We conducted a structured search of PubMed to identify potentially relevant English-language publications that assessed adherence to TNF-α inhibitors in CD. In our search strategy, the following keywords and search strings were used: (infliximab OR Remicade OR adalimumab OR Humira OR etanercept OR Enbrel OR anti-TNF OR biological) AND Crohn AND (adherence OR compliance). In the same way, we conducted a search of PubMed to identify potentially relevant publications that assessed adherence with TNF-α inhibitors in RA, thereby substituting the search term “Crohn” for “RA”. During the whole process the exact reporting guidelines as described in the PRISMA statement (http://www.prisma-statement.org) were followed.

Two investigators (Fidder HH and Singendonk MMJ) independently reviewed identified titles and abstracts of all citations in the literature search results. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved and the following predefined inclusion criteria were applied: (1) original research article; (2) adult patients; (3) definition of adherence provided; (4) methodology of measurement of adherence described; and (5) data based on number of patients. From selected abstracts, full articles were retrieved, reviewed and included if they contained data regarding adherence to TNF-α inhibitors in CD or RA. Disagreements between reviewers were adjudicated by discussion and consensus with a third-party arbiter (MvO).

The following information was extracted for each selected study: TNF-α inhibitors used, study design, sample size, definition of adherence measurement and the levels of adherence reported. We also sought for determinants of adherence in included studies, and tabulated the following factors of interest by using the presented OR: gender, age, duration of disease and therapy, prior and concomitant therapy. The data obtained from the selected articles describing adherence with TNF-α inhibitors were tabulated and also presented descriptively.

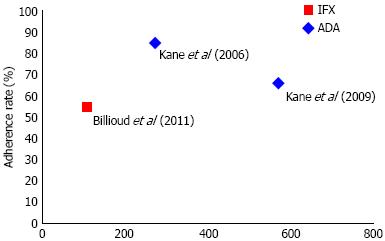

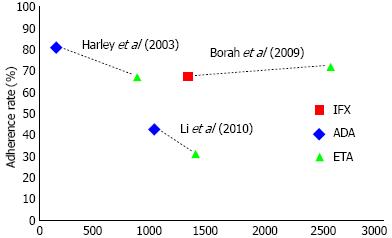

Given the large variations in definitions and methodologies of measurement of adherence and patient samples of the studies included, we used the definitions of adherence used by the authors in order to calculate the sample size-weighted pooled proportions of patients that were adherent to therapy and to compare adherence rates between adalimumab, infliximab and etanercept. To portray these data for each therapeutic agent, we graphed them alongside two axes; adherence rate reported by the selected study for each agent and number of patients included.

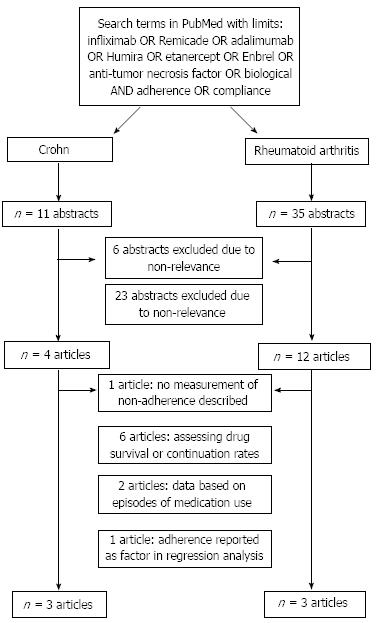

The search identified 11 studies regarding CD and 35 regarding RA, of which respectively 7 and 32 articles were excluded in two selection procedures. The main reason for exclusion of studies on CD was the absence of data on adherence or compliance (Figure 1)[8]. Exclusion of studies on RA was mainly based on the fact that these studies assessed drug survival or continuation rates only, but not compliance and/or adherence[4,9-13]. Three other studies were excluded: two studies based their data on episodes of medication use instead of number of patients[14,15] and one study only reported adherence as a factor in regression analysis[16]. Six articles that met our inclusion criteria remained, three on CD[7,17,18] and three on RA[19-21]. Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1.

| Number of patients | Anti-TNF treatment | Definition of adherence | Adherence | |

| Crohn's disease | ||||

| Kane et al[7] | 571 | Infliximab | ≥ 7 infusions in first year of treatment | 66% |

| Billioud et al[17] | 108 | Adalimumab | Neither delaying nor missing > 1 injection in 3 mo | 55% |

| Kane et al[18] | 274 | Infliximab | No "No show" designation during study period | 85% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||||

| Borah et al[19] | 2537 | Etanercept | Medication possession ratio ≥ 0.80 | 71% |

| 1292 | Adalimumab | 67% | ||

| Harley et al[20] | 853 | Etanercept | Medication possession ratio ≥ 0.80 | 68% |

| 141 | Infliximab | 81% | ||

| Li et al[21] | 1359 | Etanercept | Proportion of days covered ≥ 0.80 | 32% |

| 1012 | Infliximab | 43% | ||

Two out of three studies on CD reported on adherence to infliximab[7,18] and one on adalimumab[17]. There were no comparative studies. We identified considerable variation in the definitions and methodologies of measuring adherence between studies. The adherence rate for all TNF-α inhibitors as calculated by the sample size-weighted pooled proportion was 70% (95%CI: 67%-73%). For adalimumab, the reported adherence rate was 55%[17] and for infliximab the reported rates were 66%[7] and 85%[18] (Table 1). Adherence to adalimumab (55%) was statistically significantly lower than infliximab (72%) therapy, with a relative risk of 0.76 (95%CI: 0.64-0.91) (Figure 2)[7,17,18].

For RA we only found comparative studies: two of the included studies assessed adherence to both etanercept and infliximab[20,21] and one study compared etanercept with adalimumab[21]. In RA, measurement of adherence was based on medication possession ratios in two studies and one study measured adherence as the proportion of days covered (PDC). Medication possession rate (MPR) is defined as the sum of days supply for all fills in period divided by the number of days in a period. PDC is the number of days in a period covered by medication divided by the days in a period. In all studies patients were considered adherent if MPR or PDC was ≥ 0.8.

Reported adherence rates ranged from 32% to 81% (Table 1)[19-21]. The overall adherence rate was 59% (95%CI: 58%-60%), as calculated by the sample size-weighted pooled proportion. In the two studies comparing infliximab to etanercept adherence to infliximab was consistently higher (Figure 3)[20,21]. In the study comparing etanercept to adalimumab, patients using etanercept were slightly more adherent than adalimumab users[19]. After pooling the published adherence rates, we found the highest adherence rate for adalimumab (67%) compared to both infliximab (48%) and etanercept (59%), with a relative risk of 1.41 (95%CI: 1.3-1.52) and 1.13 (95%CI: 1.10-1.18) respectively.

Five studies have formally explored possible predictors of (non)-adherence to TNF-α inhibitors (Table 2)[7,19-21]. The most consistent factor associated with lower adherence (reported by three studies) was female gender[7,20,21]. Increasing duration of therapy was reported as a factor negatively associated with adherence and duration of disease as factor associated with better adherence[7,18]. Results for age, immunomodulator use and prior TNF-α inhibitors use were conflicting[7,19].

| Studies on Crohn's disease | Studies on rheumatoid arthritis | ||||

| Kane et al[7] | Billioud et al[17] | Kane et al[18] | Borah et al[19] | Li et al[21] | |

| Female gender | OR < 1 | OR < 1; P < 0.05 | OR < 1 | ||

| Increasing age | OR < 1 | OR > 1 | |||

| Immunomodulator use | OR > 1 | OR < 1 | OR > 1; P < 0.051 | ||

| Prior biologic use | OR < 1; P < 0.05 | OR > 1; P < 0.05 | |||

| Increasing duration of therapy | OR < 1; P < 0.05 | ||||

| Increasing disease duration | OR > 1; P < 0.05 | ||||

We systematically reviewed adherence rates to TNF-α inhibitors in CD and RA. Although literature on adherence rates to TNF-α inhibitors in other rheumatological diseases exists, we did not assess adherence for these diseases given the relatively small patient numbers. Given the central position of TNF-α inhibitors in the management of CD and RA and the importance of adherence for effective treatment, the total number of six studies that adequately assessed adherence to anti-TNF therapy was surprisingly low. Our analysis of the included studies on CD and RA has three key findings. First, we found that adherence to TNF-α inhibitors in CD and RA is low, with only two-thirds of the patients being adherent to therapy. Second, adherence rates for adalimumab were lower compared to infliximab in CD. Last, we found that female gender was consistently associated with non-adherence to TNF-α inhibitors.

Our findings of rather low adherence to TNF-α inhibitors are in line with figures reported for adherence to oral medication in inflammatory bowel disease, that range between 28% and 93% of patients adherent to prescribed therapy[5,22,23]. In a comparative cohort study mesalazine and azathioprine were associated with the lowest compliance[24]. In RA the adherence rates for TNF-α inhibitors has been reported between 30% and 80%, depending on definitions used[25]. The low adherence to TNF-α inhibitors are especially worrisome since long treatment intervals are associated with infusion reactions and loss of response as result of increased antibody formation against TNF-α inhibitors[26-28]. Moreover, non-adherence in adalimumab treated patients predicts higher hospitalization rates and increased medical service costs[7]. Adherence to continuous maintenance treatment with TNF-α inhibitors is important for the efficacy of treatment.

Although the different routes and schedules of administration of TNF-α inhibitors and the different measures of adherence across studies may impede a direct comparison, we found lower adherence rates with adalimumab and etanercept. In RA, pooling the adherence rates gave higher adherence for adalimumab over infliximab but all comparative studies reported higher adherence rates for infliximab as well. Differences in patient numbers between studies and a difference between the number of studies used for calculating the pooled adherence rates for the single treatment modalities are underlying this conflicting finding. In addition, Li et al[21] assesses adherence rates with etanercept and infliximab by using the PDC, which is a more conservative estimate for adherence compared to the MPR. Discrepant adherence between treatment options may be explained by a number of reasons including dosing frequency and route of administration. Etanercept and adalimumab are self-administered subcutaneously, whereas infliximab is administered intravenously, by a healthcare professional in a clinical setting. As patients need to visit infusion sites, adherence is more controllable in favor of infliximab. Indeed, in the two comparative studies between infliximab and etanercept[20,21], higher adherence was found for the intravenously administered infliximab. In the study of Borah et al[19] adherence of etanercept - which is injected once or twice a week - was slightly higher than adalimumab, which is mostly self-administered using a bi-weekly schedule. But still, even for the more controllable intravenously administered modalities, adherence rates are well below 100%.

In order to improve adherence, it is essential to identify and understand risk factors for non-adherence. Although several factors were reported as determinants of adherence by the reviewed studies, we did not find any of these factors consistently associated with non-adherence, with the exception of female gender. This is in contrast with a previous study on oral therapies in inflammatory bowel disease that identified female gender as a positive determinant of adherence[29]. Also in other fields of medicine attempts to identify clinical, demographic and treatment factors that consistently predict adherence have proven quite disappointing[6]. Jackson et al[5] who systematically reviewed factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication specifically for inflammatory bowel disease pointed out that that simple factors such as demographics or treatment regimens could not reliably predict adherence. Far more important determinants were psychological distress, patients’ beliefs about therapy, and doctor-patient interactions[5]. For the clinician, it is essential to be aware of the importance of psychological factors in non-adherence and that significant improvement in terms of adherence may be achieved by fine-tuning doctor-patient communication and addressing patients’ individual beliefs about disease and medications.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. We provided a detailed and systematic review of published literature and studied adherence rates on both CD and RA with TNF-α inhibitors. Koncz et al[30] reviewed compliance and persistence for TNF-α inhibitors only in RA patients. Contrary to this review we included only studies that assessed adherence rates based on number of patients included and reported individual adherence results. Furthermore, we identified potential predictors of adherence. In the evaluation of potential predictors of adherence, we had no access to original research data and therefore we were dependent on the analyses performed by others and could not perform an individual patient data meta-analysis. The major drawback of this approach is the lack of agreement in terminology and methodologies for measurement of therapy behaviour, making the results of studies assessing this issue difficult to interpret and compare. Compliance, persistence and adherence are definitions used for assessing this. The medication possession ratios of infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab ranged between 63% and 90% and PDC around 40%. The PDC provides a more conservative estimate of adherence compared to MPR when patients are switching drugs or using dual-therapy in a class. The differences between these terms have been defined in a report for the National Institute for Health Research by Mikkelsen et al[31] Compliance can be defined as “the extent to which the patients” behaviour matches the prescriber’s recommendations’ quantified as “a percentage of number of doses taken or therapy days available in relation to a fixed period of time’’. Persistence refers to how long the patient takes the medicine for and is therefore measured by units of time. Adherence covers both these aspects of medication taking behaviour. Although these definitions seem clear, methodologies of measurement vary and therefore hinder comparability of findings. These differences in measurement of adherence cannot be shrugged aside, but at this stage, based on currently available literature, we provided more insight in the TNF-α therapy behaviour of patients with CD and RA. Despite the mentioned limitations, it is still clear that adherence with TNF-α therapy is low for all different modalities. However, there is no clarity on what levels of adherence are required for optimal results of therapy yet and these levels might vary depending on disease activity and localization. Therefore, in the future adherence should be assessed in combination with therapy outcome in order to determine optimal treatment schedules by using uniform definitions of compliance, adherence and persistence.

In conclusion, through systematic review we found that only two-third of the patients with CD and RA receiving TNF-α inhibitors were adherent to therapy. Developing methods that properly assess medication adherence could provide tools for improvement of therapy outcome. Although female gender was identified as a negative determinant of adherence, one should be aware that mechanisms underlying adherence are complicated and probably not determined by simple patient’s and treatment characteristics.

Crohn’s disease (CD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are chronic inflammatory conditions characterized by episodes of remission and flare-ups that have a major impact on the patient’s physical, emotional and social well-being. The management of these diseases has been profoundly modified by the introduction of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) inhibitors.

Clinical effectiveness of TNF-α inhibitors is dependent on adequate adherence, and failure to stick to the prescribed drug regimen contributes to failure of treatment and disease recurrence. For both RA and CD, good adherence is associated with more effective treatment, including limited loss of response.

The analysis of the included studies on CD and RA has three key findings. First, the authors found that adherence to TNF-α inhibitors in CD and RA is low, with only two-thirds of the patients being adherent to therapy. Second, adherence rates for adalimumab were lower compared to infliximab in CD. Last, they found that female gender was consistently associated with non-adherence to TNF-α inhibitors.

The authors found that only two-third of the patients with CD and RA receiving TNF-α inhibitors were adherent to therapy. Developing methods that properly assess medication adherence could provide tools for improvement of therapy outcome.

This article investigated adherence rates inTNF-α-inhibitors in CD and RA by systematic review of medical literature, and is informative and well-presented.

P- Reviewer Chiba T S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Ma S

| 1. | Furst DE, Keystone EC, Braun J, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, De Benedetti F, Dörner T, Emery P, Fleischmann R, Gibofsky A. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2011. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71 Suppl 2:i2-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, Hanauer SB, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644-659, quiz 660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fernández-Nebro A, Irigoyen MV, Ureña I, Belmonte-López MA, Coret V, Jiménez-Núñez FG, Díaz-Cordovés G, López-Lasanta MA, Ponce A, Rodríguez-Pérez M. Effectiveness, predictive response factors, and safety of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapies in anti-TNF-naive rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2334-2342. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:525-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD000011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 770] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kane SV, Chao J, Mulani PM. Adherence to infliximab maintenance therapy and health care utilization and costs by Crohn’s disease patients. Adv Ther. 2009;26:936-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Juillerat P, Pittet V, Vader JP, Burnand B, Gonvers JJ, de Saussure P, Mottet C, Seibold F, Rogler G, Sagmeister M. Infliximab for Crohn’s disease in the Swiss IBD Cohort Study: clinical management and appropriateness. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1352-1357. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Brocq O, Roux CH, Albert C, Breuil V, Aknouche N, Ruitord S, Mousnier A, Euller-Ziegler L. TNFalpha antagonist continuation rates in 442 patients with inflammatory joint disease. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:148-154. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hetland ML, Lindegaard HM, Hansen A, Pødenphant J, Unkerskov J, Ringsdal VS, Østergaard M, Tarp U. Do changes in prescription practice in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biological agents affect treatment response and adherence to therapy Results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO Registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1023-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, Dreyer L, Hansen A, Hansen IT, Kollerup G, Linde L, Lindegaard HM, Poulsen UE. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:22-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marchesoni A, Zaccara E, Gorla R, Bazzani C, Sarzi-Puttini P, Atzeni F, Caporali R, Bobbio-Pallavicini F, Favalli EG. TNF-alpha antagonist survival rate in a cohort of rheumatoid arthritis patients observed under conditions of standard clinical practice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1173:837-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wendling D, Materne GE, Michel F, Lohse A, Lehuede G, Toussirot E, Massol J, Woronoff-Lemsi MC. Infliximab continuation rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in everyday practice. Joint Bone Spine. 2005;72:309-312. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Grijalva CG, Chung CP, Arbogast PG, Stein CM, Mitchel EF, Griffin MR. Assessment of adherence to and persistence on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Med Care. 2007;45:S66-S76. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Grijalva CG, Kaltenbach L, Arbogast PG, Mitchel EF, Griffin MR. Adherence to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and the effects of exposure misclassification on the risk of hospital admission. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:730-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Curkendall S, Patel V, Gleeson M, Campbell RS, Zagari M, Dubois R. Compliance with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: do patient out-of-pocket payments matter. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1519-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Billioud V, Laharie D, Filippi J, Roblin X, Oussalah A, Chevaux JB, Hébuterne X, Bigard MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Adherence to adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease: a French multicenter experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:152-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kane S, Dixon L. Adherence rates with infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1099-1103. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Borah BJ, Huang X, Zarotsky V, Globe D. Trends in RA patients’ adherence to subcutaneous anti-TNF therapies and costs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1365-1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harley CR, Frytak JR, Tandon N. Treatment compliance and dosage administration among rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving infliximab, etanercept, or methotrexate. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:S136-S143. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Li P, Blum MA, Von Feldt J, Hennessy S, Doshi JA. Adherence, discontinuation, and switching of biologic therapies in medicaid enrollees with rheumatoid arthritis. Value Health. 2010;13:805-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bokemeyer B, Teml A, Roggel C, Hartmann P, Fischer C, Schaeffeler E, Schwab M. Adherence to thiopurine treatment in out-patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:217-225. [PubMed] |

| 23. | López San Román A, Bermejo F, Carrera E, Pérez-Abad M, Boixeda D. Adherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:249-257. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bernal I, Domènech E, Garcia-Planella E, Marín L, Mañosa M, Navarro M, Cabré E, Gassull MA. Medication-taking behavior in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2165-2169. [PubMed] |

| 25. | van den Bemt BJ, van Lankveld WG. How can we improve adherence to therapy by patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:681. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, Noman M, Katsanos K, Segaert S, Henckaerts L, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: the Mayo clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19-31. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, D’ Haens G, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601-608. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2929-2933. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Koncz T, Pentek M, Brodszky V, Ersek K, Orlewska E, Gulacsi L. Adherence to biologic DMARD therapies in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1367-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |