Published online Jul 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4316

Revised: March 19, 2013

Accepted: April 13, 2013

Published online: July 21, 2013

Processing time: 275 Days and 11.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the clinical value of endoscopic papillectomy indicated by feasibility and safety of the procedure in various diseases of the papilla in a representative number of patients in a setting of daily clinical and endoscopic practice and care by means of a systematic prospective observational study.

METHODS: Through a defined time period, all consecutive patients with tumor-like lesions of the papilla, who were considered for papillectomy, were enrolled in this systematic bicenter prospective observational study, and subdivided into 4 groups according to endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) findings as well as histopathological diagnosis: adenoma; carcinoma/neuroendocrine tumor (NET)/lymphoma; papilla into which catheter can not be introduced; adenomyomatosis, respectively. Treatment results and outcome were characterized by R0 resection, complication, recurrence rates and tumor-free survival.

RESULTS: Over a 7-year period, 58 patients underwent endoscopic papillectomy. Main symptoms prompting to diagnostic measures were unclear abdominal pain in 50% and cholestasis with and without pain in 44%. Overall, 54/58 patients [inclusion rate, 93.1%; sex ratio, males/females = 25/29 (1:1.16); mean age, 65 (range, 22-88) years] were enrolled in the study. Prior to papillectomy, EUS was performed in 79.6% (n = 43/54). Group 1 (adenoma, n = 24/54; 44.4%): 91.6% (n = 22/24) with R0 resection; tumor-free survival after a mean of 18.5 mo, 86.4% (n = 19/22); recurrence, 13.6% (n = 3/22); minor complications, 12.5% (n = 3/24). Group 2 (carcinoma/NET/lymphoma, n = 18/54; 33.3%): 75.0% (n = 12/18) with R0 resection; tumor-free survival after a mean of 18.5 (range, 1-84) mo, 88.9% (n = 8/9); recurrence, 11.1% (n = 1/9). Group 3 (adenomyomatosis, n = 4/54; 7.4%). Group 4 (primarily no introducible catheter into the papilla, n = 8; 14.8%). The overall complication rate was 18.5% (n = 10/54; 1 subject with 2 complications): Bleeding, n = 3; pancreatitis, n = 7; perforation, n = 1 (intervention-related mortality, 0%). In summary, EUS is a sufficient diagnostic tool to preoperatively clarify diseases of the papilla including suspicious tumor stage in conjunction with postinterventional histopathological investigation of a specimen. Endoscopic papillectomy with curative intention is a feasible and safe approach to treat adenomas of the papilla. In high-risk patients with carcinoma of the papilla with no hints of deep infiltrating tumor growth, endoscopic papillectomy can be considered a reasonable treatment option with low risk and an approximately 80% probability of no recurrence if an R0 resection can be achieved. In patients with jaundice and in case the catheter can not be introduced into the papilla, papillectomy may help to get access to the bile duct.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic papillectomy is a challenging interventional approach but a suitable patient- and local finding-adapted diagnostic and therapeutic tool with adequate risk-benefit ratio in experienced hands.

Core tip: Taken together, endoscopic ultrasonography is an essential and sufficient diagnostic tool and plays an eminent role in the diagnostic spectrum to preoperatively clarify lesions and diseases of the papilla in conjunction with the competent postinterventional histopathological investigation of a specimen. Endoscopic papillectomy with curative intention is a feasible and safe approach to treat adenomas of the papilla, i.e., it is only reasonable if there is no infiltrating tumor growth. In high-risk patients with carcinoma of the papilla but no hints of deep infiltrating tumor growth, endoscopic papillectomy can be considered a reasonable treatment option with reduced risk and an approximately 80% probability of no recurrence if an R0 resection can be achieved. In patients with jaundice and in case the catheter can not be introduced into the papilla, papillectomy may help to get access to the bile duct to avoid more traumatic surgery. Endoscopic papillectomy is therefore not only used for therapeutic but also for diagnostic purpose. There is a high clinical value of endoscopic papillectomy for well defined indications not only for adenoma but also for carcinoma/neuroendocrine tumor/lymphoma (uT1 and high-risk patient), and adenomyomatosis. Follow-up investigations according to a defined schedule appear to be reasonable including macroscopic assessment, taking a representative biopsy and subsequent histopathological investigation. In addition, continuous systematic investigation of endoscopic papillectomy in daily clinical practice is indicated for the purpose of quality assurance.

- Citation: Will U, Müller AK, Fueldner F, Wanzar I, Meyer F. Endoscopic papillectomy: Data of a prospective observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(27): 4316-4324

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i27/4316.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i27.4316

The adequate management of diseases of the papilla of Vater (papilla) is challenging. There are several morphological changes and lesions of the papilla such as functional dysfunction, inflammation, stenosis or malignant tumor growth. For instance, a stenosis of the papilla is subdivided based on an autopsy registry as follows: Benign lesions, 42.7% (frequency); adenoma (premalignant lesion), 19.6%; carcinoma, 37.7%[1].

The incidence of malignant tumor lesions of the papilla has been reported to be 0.5/100000. Based on the concept of an anticipated adenoma-carcinoma sequence even at the papilla[2,3], adenoma is considered a premalignant tumor lesion[4-7], e.g., adenomatous portions can be found in 35% to 91% of the histologically detected carcinomas. In this context, the incidence of an occurring carcinoma in papillary adenoma is 1 over 15.5 patient years.

Diagnostic measures of pathological changes at the papilla are a complex challenge since a differential and stage-adapted treatment depends on the early set-up of the correct diagnosis. Combination of clinical exam, laboratory parameters and abdominal ultrasound provides a sensitivity of up to 100% to diagnose cholestasis. However, the accuracy in characterizing the cause of cholestasis is considerably lower.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) may solve the dilemma since it allows to clarify etiopathogenesis and actual diagnosis in the vast majority of cases[1]. In addition, this diagnostic measure provides a sensitivity of up to 100% in detecting tumor-like lesions at the papilla or within the peripapillary region and, in addition, it enables the investigator to characterize tumor infiltration status and possible involvement of lymphatic tumor growth according to TNM staging[8]. Furthermore, taking a biopsy becomes possible by an adequate imaging.

Whether in case of a tumor lesion of the papilla, endoscopic intervention such as papillectomy or surgical intervention is used depends on tumor entity, tumor stage and individual characteristics of the patient[9-11].

Today, the spectrum of indications for endoscopic papillectomy comprises adenoma, carcinoma of stage uT1N0[12-18], neuroendocrine tumor (NET)[8,19,20], non-introducible catheter into the papilla[21], cholestasis and diagnostic purpose. Ponchon et al[22] and Binmoeller et al[9] reported on endoscopic papillectomy for the first time. Further therapeutic options in adenoma are kephal pancreaticoduodenectomy and local surgical resection (ampullectomy) via a transduodenal approach. But in case of resectable carcinoma of the papilla, surgical intervention is the treatment of choice since there is a probability of approximately 20%-40% of manifest lymph node metastases if there is a submucosal infiltration.

The aim of the study was to investigate the clinical value of endoscopic papillectomy indicated by feasibility[16] and safety of the procedure in various diseases of the papilla in a representative number of patients in a setting of daily clinical and endoscopic practice and care by means of a systematic prospective observational study, to balance advantages and disadvantages of the endoscopic approach, as well as, in particular, to elucidate: (1) Which were the main and propper indications (2) What results of resections could be achieved or (3) What was the long-term outcome in various diseases of the papilla

Through a defined time period, all consecutive patients with tumor-like lesions of the papilla who were selected for an endoscopic approach, were enrolled in this systematic bicenter prospective observational study (design). In addition to physical exam and laboratory analysis, the patients underwent upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy including EUS. Endoscopic papillectomy (modified procedure according to Han and Kim[23]) was chosen in case of promising potential for R0 resection, in uT1 lesions with no hints of deep infiltrating tumor growth and/or in high-risk patients (balancing risk-benefit ratio of open surgery) after appropriate diagnostics (imaging and/or biopsy) and additional decision-making in the institutional multi-disciplinary GI tumor board. It was performed by only 2 experienced interventional endoscopists as follows, in brief: Patients underwent papillectomy during upper GI endoscopy after signing informed consent the day before intervention, in particular, containing information on risk, complication profile and major complications such as acute pancreatitis, perforation and bleeding as well as necessary follow up and prognosis of each specific procedure as appropriate, “npo” for 12 h, and premedication with 5-10 mg Midazolam (Midazolam Ratioph®, Ratiopharm GmbH, Ulm, Germany) under antibiotic prophylaxis with ceftriaxone (Rocephin®, 2 g; Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany) and cardiopulmonal monitoring.

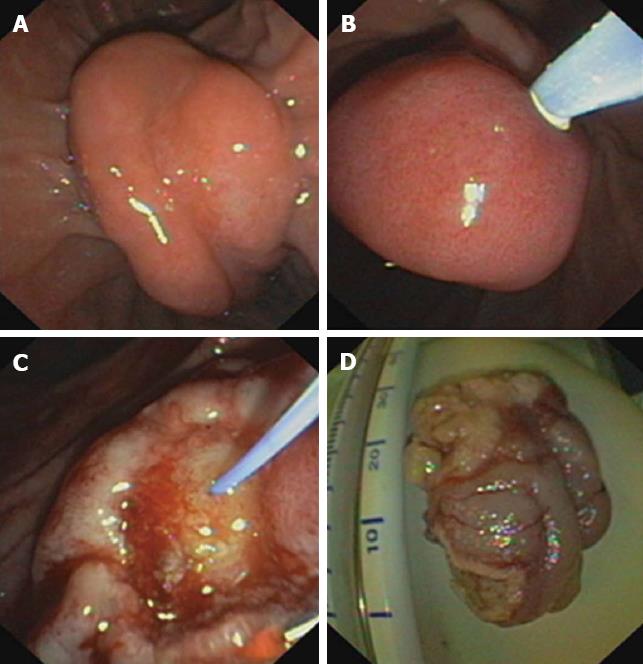

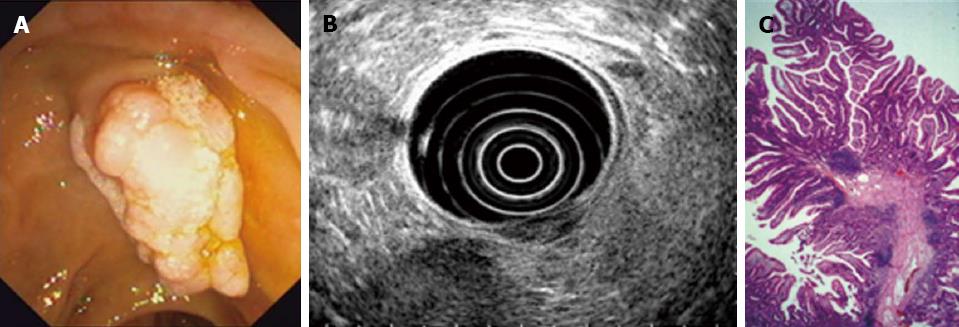

Using a duodenoscope [Olympus Optical Co. (Europe) GmbH, Hamburg, Germany], peripapillary region was endoscopically inspected (Figures 1 and 2) eventually completed by diagnostic EUS (Hitachi Medical Systems, Lübbecke, Germany) (Figure 2B), and cholangiography was performed if possible (catheter which can be introduced into the papilla). Papillectomy was executed using high frequency diathermia loop (MTW Endoskopie, Wesel, Germany) (Figure 1C and D). If required, sphincterotomy using papillotome [Olympus Optical Co. (Europe) GmbH, Hamburg, Germany] to prevent postinterventional stenosis; stent implantation into the pancreatic duct (5-French plastic endoprosthesis; GIP Medizintechnik GmbH, Achenmühle, Germany) for 4-5 d to drain the pancreas sufficiently because of possible postinterventional swelling of the papilla and peripapillary region[24]; and/or APC (Erbe APC, Medika, Hof, Germany), in particular, to encrust tumor residuals with electrocoagulation were combined. Bleedings were immediately tried to be controlled as appropriate using adrenalin injection (dilution, 1:10000), fibrin glue application (Baxter Deutschland GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and/or placement of hemoclips [Olympus Optical Co. (Europe) GmbH, Hamburg, Germany]. Specimens were immediately transferred to routine histopathological investigation (Figure 2C) and followed by specific stainings and/or immunohistochemistry if necessary.

Data such as clinicopathological features (age, sex, gender, symptomatology leading to initiation of diagnostic, diagnostic profile and findings, spectrum of diagnoses, tumor size, TNM stage and occurrence of metastases in case of malignancy, profile of indications for papillectomy) were prospectively collected, documented using a computer-based registry and retrospectively evaluated using SPSS for Windows (version 13.0, Chicago, IL, United States).

The patients were subdivided into 4 groups according to endoscopic and EUS findings as well as the histopathological diagnosis: Group 1: Adenoma; Group 2: Carcinoma/NET/lymphoma; Group 3: Papilla into which catheter can not be introduced; Group 4: Adenomyomatosis.

Treatment results were characterized by R0 resection and complication rate, the latter one further specified by periinterventional morbidity and intervention-related mortality. Outcome was assessed by recurrence rate as well as general and tumor-free survival after a long-term period of follow-up investigations which were performed using clinical exam, abdominal ultrasound and endoscopy with biopsy as well as EUS (if required) every 3-6 mo for 2 years followed by time intervals of 6 mo in cases of adenomas and malignant tumor growth (but immediately if required and indicated by suspicuous symptomatology).

Study was performed according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for Biomedical Research from 1964 and the standards of the Institutional Review Board.

Data were evaluated by descriptive statistics and further analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 13.0, Chicago, IL, United States) to proof validity of the preinterventional histopathological diagnosis by means of binary diagnostic tests such as 2 × 2 square panel, which allows to determine sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values as appropriate.

Through a 7-year study period, endoscopic papillectomy was performed in 58 patients at the Departments of Gastroenterology of the University Hospital in Jena (Germany) and the Municipal Hospital in Gera (Germany). Overall, 54 patients were evaluated (inclusion rate, 91.6%; 25 males (M), 29 females (F); sex ratio, M/F = 1:1.16). The mean age was 64.4 years in males, in females 67 years (range, 22-88 years).

The main clinical symptoms were predominated by abdominal pain in 50% of cases followed by cholestasis in 33%. The combination of both was found in 11% (others, 6%).

All tumors were detectable, imaged and characterized with regard to the locoregional tumor growth using various diagnostic tools (detection rate, 100%). Tumor size ranged between 1 and 4.5 cm. The spectrum and frequency of endoscopic investigations to proof the indication of endoscopic papillectomy is shown in Table 1. It clearly shows that EUS was the most frequent endoscopic procedure in more than 3/4 half of cases (79.6%). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was only used in less than 50% of patients (44.8%; gastroscopy, 51.8%). Interestingly, gastroscopy contributed to achieve a histopathological finding by taking a biopsy in the majority of cases.

| Investigation | Gastroscopy | EUS | ERCP | |||

| w/Hx | w/o Hx | w/Hx | w/o Hx | w/Hx | w/o Hx | |

| Case n (%) | 20 (37.0) | 8 (14.8) | 4 (7.4) | 39 (72.2) | 9 (16.6) | 15 (27.8) |

| In total (%) | 51.80% | 79.60% | 44.40% | |||

Histopathological diagnosis was determined in 32 patients in whom preinterventional histopathological investigation was performed which was distributed as indicated in Table 2 whereas slightly different, there was a profile and frequency of indications, which led to endoscopic papillectomy as a result of preinterventional diagnostic measures (n = 54; Table 2), and finally endoscopic papillectomy with subsequent histopathological investigation resulted in the distribution of definitive histopathological diagnoses as listed in Table 2 (n = 54).

| Category of single finding | Preinterventional histo-pathological finding (after taking a biopsy; n = 32) | Indications leading to endoscopic papillectomy (result of preinterventional diagnostic measures; n = 54) | Definitive histopathological findings of the specimen (after endoscopic papillectomy; n = 54) |

| Adenoma | |||

| Tumor mass with no malignancy | 63 | 35 (64.8) | 24 (45.0) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 19 | 10 (18.5) | 18 (33.0) |

| NET | 3 | ||

| Lymphoma | 3 | ||

| Mucosal specimen | 9 | / | / |

| Papilla into which catheter can not be introduced | / | 8 (14.8) | 8 (15.0) |

| Diagnostic papillectomy | / | 1 (1.8) | / |

| Adenomyomatosis | / | / | 4 (7.0) |

This resulted in a cumulative sensitivity and specificity for preinterventional histopathological findings such as adenoma and carcinoma/NET/lymphoma of 64.2% and 55.0%, respectively. The negative and positive predictive values were 65.5% and 56.5%, respectively. Interestingly and in combining the diagnoses adenoma and carcinoma/NET/lymphoma in the preinterventional diagnostic measures, there were a sensitivity of 64.2%, a specificity of 65.5%, a negative predictive value of 65.5% and a positive predictve value of 56.5%, respectively, for the preinterventional diagnostic measures (Table 3).

| Parameter | Pre-interventional | |

| Histopathological investigation (after taking a biopsy) | Diagnostic measures | |

| Sensitivity | 64.20% | 64.20% |

| Specificity | 55.00% | 65.50% |

| Predictive value | ||

| Negative | 65.5% | 65.5% |

| Positive | 56.5% | 56.5% |

In adenomas (patient group 1, Table 4), there was a tumor recurrence rate of 13.6% (n = 3/22). Interestingly, there were two cases in whom no R0 resection was achieved but aspects of recurrent adenomatous tumor growth have not been observed yet during the follow-up investigation period. Recurrent adenomas were re-approached using endoscopic papillectomy with good success.

| Adenoma | ||||||

| In total | Resectiom status | |||||

| R0 | Rx | R0 + Rx | R1 | R2 | ||

| Case | 24 | 9 (37.5) | 13 (54.2) | 22 (91.6) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) |

| Recurrence | 1 (11.1) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (13.6) | |||

Considering all patients with malignant tumor growth, i.e., all tumor lesions and stages (Table 5; patient group 2; n = 18:13 patients with adenocarcinoma, 4 individuals with NET, and one subject with a lymphoma), there was a recurrence rate of 20.0% [n = 2/10 (R0 + Rx)] after a mean follow-up investigation period of 18.5 (range, 1-84) mo. The two cases out of ten with recurrent carcinoma were transfered to abdominal surgery with favorable outcome. According to the results listed in Table 5, 12 patients with the more relevant uT1 carcinoma for a minimally invasive, endoscopic approach underwent endoscopic papillectomy with curative intention, in whom R0 resection status was achieved in 9 patients (75%) while no tumor recurrence was found in 88.9% of patients (n = 8/9). The one patient with R1 and the seven patients with R2 resection status were re-approached using Argon beamer with a good long-term result (no recurrent tumor growth within the reported follow-up investigation period). Rescue surgical intervention did not become necessary in case of R1/R2 resection since all of these patients had been classified of high perioperative risk.

| In total | Resection status | |||||

| R0 | Rx | R0 + Rx | R1 | R2 | ||

| All stages | ||||||

| Case | 18 | 8 (44.4) | 2 (11.1) | 10 (55.5) | 1 (5.5) | 7 (38.8) |

| Recurrency | 1 (12.5) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| T1 stage only | ||||||

| Case | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 1 (8.3) | 9 (75.0) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.6) |

| Recurrence | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | |||

In cases of a papilla into which catheter can not be introduced (n = 8; patient group 3) for which there are no data from the literature, the catheter placement was achieved in 87.5% (n = 7/8) of cases after endoscopic papillectomy. A re-intervention because of a stent occlusion became necessary in 2 patients (no table shown).

If an adenomyomatosis (n = 4) was diagnosed (patient group 4), there was a successful papillectomy in 100% of cases with no necessary reinterventions (again, no table shown).

Overall, there was a successful endoscopic papillectomy with regard to R0/Rx resection and/or placement of a catheter into the papilla in case of former not introducible catheter in 87.5% (n = 42/48) according to technical success rate, but related to no tumor recurrence and/or placement of a catheter into the papilla in 79% (n = 38/48) according to clinical success rate. The basis for this calculation was the number of 48 patients since there were 6 patients with a tumor stage T > 1Nx (Table 5; n = 18 min nuT1 = 12).

As shown in Table 6, complications occured in 18.5% (n = 10/54), in particular, bleeding (n = 3); pancreatitis (n = 7) and perforation (n = 1; the only case with need for rescue surgical intervention) (Table 6), in 12.5% (n = 3/24) of adenoma patients (Table 6) but no postinterventional stenosis of the orifice at the papilla was observed (major complication rate, 1.9%; n = 1/54; Table 6). There was no intervention-related death (mortality, 0%).

| Case (n) | Complications | |

| Adenoma | 24 | 3 (12.5) |

| Carcinoma/NET/lymphoma | 18 | 3 (16.6) |

| Papilla into which catheter can not be introduced | 8 | 2 (25.0) |

| Adenomyomatosis | 4 | 2 (50.0) |

| In total | 54 | 10 (18.5) |

| Major complication | 1 (1.9) |

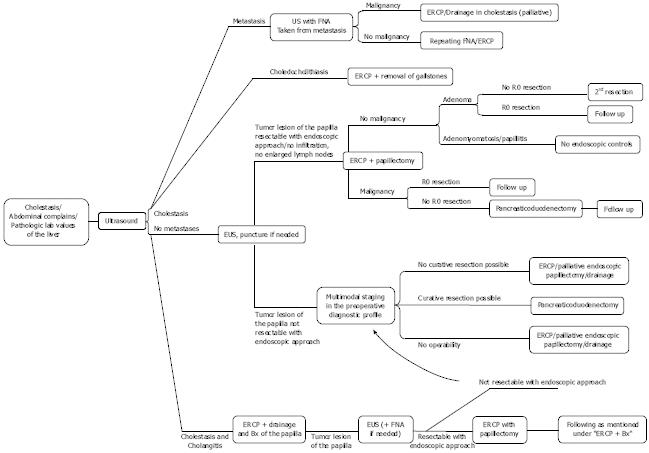

In addition to clinical exam, laboratory analysis, and abdominal ultrasound, EUS[8] and ERCP[25,26] are the appropriate diagnostic measures for suspected tumor (-like) lesions of the papilla. Furthermore, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography can be performed to further assess local tumor growth including possible tumor infiltration to the neighboring organs and to detect distant metastases (suggested institutional diagnostic algorithm including therapeutic measures, Figure 3). However, EUS appears to be the best diagnostic tool, which is able to reliably predict the correct diagnosis with a high percentage prior to papillectomy[1].

In a suspected local tumor lesion, a papillectomy can be helpful to clarify the diagnosis, in particular, in getting access to the obstructed bile duct; to remove a representative specimen; or to even provide adequate resection[9,10,24] since in non-clear benign or malignant tumor growth, an early, correct and reliable diagnosis-finding allows an appropriate subsequent therapeutic decision-making according to differential diagnosis and stage of disease[2].

Interestingly, a curative resection is possible by the means of minimally invasive endoscopic intervention under certain circumstances such as adenoma of smaller size[5-7,9,10,24] and uT1 carcinoma[12] with no hints of deep infiltrating tumor growth if R0 resection status can be achieved or in high-risk patients[6] though carcinoma is usually an indication for surgical intervention[2].

Also in case of a catheter which can not be introduced into the papilla (into the minor papilla[27] if there is a suspected “pancreas divisum” or into the major papilla after previous gastric resection [Billroth II] or because of a carcinoma of the papilla[12]) and even if an adenomyomatosis is detected, there is need for endoscopic papillectomy since, on one hand, access to the pancreaticobiliary system is needed and, on the other hand, adenomyomatosis can not be macroscopically distinguished from an adenoma.

If an R0 resection was achieved, recommended follow-up investigation periods are every 6 mo for 2 years followed by further endoscopic control in case of suspicious symptoms[2]. In addition, a colonoscopy is basicly recommended. If there is an incomplete resection of an adenoma, the case needs to be controlled within 2-3 mo.

Interestingly, complication rate was similar or lower than those reported in the literature[4,9,13,14,16-19,25].

The tumor recurrence rate of 20.0% [n = 2/10 (R0 + Rx); Table 5] appears well comparable with data from the literature (Bohnacker et al[5], 15%)[10,13,14,16-18,25] as well as within the range of results in local surgical resection and kephal pancreatoduodenectomy.

The endoscopic approach in uT1 carcinoma (nuT1 = 12 out of n = 18 including all tumor stages, Table 5) correlates with recommendations of specific guidelines that endoscopic papillectomy can be reasonable in patients with uT1 and increased perioperative risk because of considerable comorbidity[2,6,10,12].

To our knowledge, this is one of the rare reports on the systematic investigation of endoscopic papillectomy in suspicious tumor lesions of the papilla in a representative number of patients[4,9,10,19,22,25] and their variety of tumor (-like) lesions as shown since there is a lack of extensive experiences because of their low incidence and the fact that optimal management of such tumor lesions has not yet been established[28].

The results justify endoscopic papillectomy as a reasonable, suitable and safe therapeutic measure in experienced hands[2,4,9,13-19,24] for the management of the broad spectrum of possible findings at the papilla or the minor papilla[27] in our institution and as occuring in daily clinical practice.

Finally, endoscopic papillectomy is considered a reasonable alternative to the “precut“ or to PTCD. For comparison, endoscopic drainage provides a success rate of 95.4% (mortality, 0%) in acute cholangitis according to the literature whereas surgical intervention is associated with a lower success rate of 58% but a mortality of up to 12.4%.

However, there are limitations of the study with regard to the overall treatment results, which can be related to: the impact of the learning curve despite only two experienced interventional endoscopists performed papillectomy; the pitfalls of papillectomy such as potential of no achievable R0 resection despite curative intention, and the complication profile (including bleeding and perforation with possible need of surgery); and no strict study inclusion criteria since study design represents a “systematic prospective bicenter observational study” reflecting daily clinical practice and consecutive but not selected patients.

In conclusion, endoscopic papillectomy is a challenging interventional approach but a suitable patient- and local finding-adapted diagnostic and therapeutic tool with adequate risk-benefit ratio in experienced hands.

The adequate management of diseases of the papilla of Vater (papilla) is challenging. There are several morphological changes and lesions of the papilla such as functional dysfunction, inflammation, stenosis or malignant tumor growth. For instance, a stenosis of the papilla is subdivided based on an autopsy registry as follows: Benign lesions, 42.7% (frequency); adenoma (premalignant lesion), 19.6%; carcinoma, 37.7%. For the treatment of tumor lesions of the papilla, it is required in addition to a sufficient histopathological investigation to achieve an adequate pretherapeutic tumor staging, which allows a decision-making toward the appropriate treatment (surgical intervention, papillectomy, papillotomy) according to the patient´s specific finding. These requirements can be fulfilled by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for the majority of tumor (-like) lesions. For the specific clinical status of the single patient (e.g., high risk because of accompanying diseases) and to cover the need of lower invasiveness and interventional trauma for a more favorite outcome as well as earlier reconvalescence, an additional approach to open surgery (providing transduodenal papillectomy/ampullectomy but with a substantial complication rate) is required-this might be provided by the very specific interventional endoscopic approach, named endoscopic papillectomy.

To provide a substantial contribution to the important field of interventional endoscopy with a low number of valuable studies and case numbers on (endoscopic) papillectomy/tumor (-like) lesions of the papilla, the aim of the study was to investigate the clinical value of endoscopic papillectomy (to broaden the spectrum of therapeutic options in managing tumor lesions of the papilla of Vater) indicated by feasibility and safety of the procedure in various diseases of the papilla in a representative number of patients in a setting of daily clinical and endoscopic practice and care by means of a systematic prospective observational study, which can be considered one of the rare study approaches existing so far and emphasizing this measure of interventional endoscopy on one hand and, on the other hand, this type of study to sufficiently characterize daily clinical (endoscopic) practice in addition to rather specifically initated comparative (controlled randomized) studies.

Endoscopic papillectomy (based on sufficient preinterventional diagnostics by, among others (in particular), EUS as a sufficient diagnostic measure to preoperatively clarify diseases of the papilla including suspicious tumor stage in conjunction with postinterventional histopathological investigation of a specimen) is a challenging interventional approach. Thus, endoscopic papillectomy can be considered a valuable addition in the (diagnostic and) therapeutic management of (peri-) ampullary (tumor-like) lesions if treated patients are systematically and prospectively analyzed for quality assurance and adequately followed, e.g., with appropriate follow-up investigations within reasonable time intervals.

Again, endoscopic papillectomy is a challenging interventional approach but a suitable patient- and local finding-adapted diagnostic and therapeutic tool with adequate risk-benefit ratio in experienced hands. Derived from this, an increasing number of interventional endoscopists may (based on and derived from the experiences analyzed in the systematic clinical prospective observational study presented here) begin with the endoscopic approach of papillectomy in their own endoscopic practice.

Papilla of Vater: important anatomic structure at the mouth of the bile duct and/or pancreatic duct with possible inflammatory and neoplastic lesions leading to unspecific or varying symptomatology. Papillectomy: interventional (challenging endoscopic) or open surgical procedure intending to completely remove papilla of Vater in specific, in particular, neoplastic [benign or malignant (in early lesions)] findings to provide low invasiveness and complication rate but making sure a case-, finding- and risk-adapted approach. Endoscopic ultrasonography: very suitable diagnostic tool, in particular, for the periampullary region but also feasible for image-guided interventional endoscopic procedures such as papillectomy (or removal of small tumor lesions, biopsy, puncture, injection). Adenoma is considered a benign neoplastic lesion originating from adenoid structures such as the superficial layer of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and, in particular, is an important lesion of the anatomic region such as papilla of Vater or the periampullary region.

The manuscript provides additional information to the existing literature obtained by a systematic prospective observational study characterizing in particular daily clinical practice in interventional endoscopy of a GI endoscopy center on feasibility and safety of endoscopic papillectomy for various tumor (-like) lesions of the papilla in a representative number of patients, which can be considered one of the rare study approaches existing so far and emphasizing this measure of interventional endoscopy on one hand and, on the other hand, this type of study to sufficiently characterize daily clinical (endoscopic) practice in addition to rather specifically initated comparative (controlled randomized) studies. In detail, endoscopic papillectomy was found to be feasible and safe in experienced hands. The clinical researchers and experienced/advanced GI endoscopists should be encouraged to further pursue this type of study, lesions and patients experiencing this challenging type of tumor (-like) lesion of the papilla, for which only a few experts can provide similar results and expertise.

P- Reviewer Kubota K S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Will U, Bosseckert H, Meyer F. Correlation of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for differential diagnostics between inflammatory and neoplastic lesions of the papilla of Vater and the peripapillary region with results of histologic investigation. Ultraschall Med. 2008;29:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bohnacker S, Soehendra N, Maguchi H, Chung JB, Howell DA. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the papilla of vater. Endoscopy. 2006;38:521-525. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Stolte M, Pscherer C. Adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the papilla of Vater. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:376-382. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Catalano MF, Linder JD, Chak A, Sivak MV, Raijman I, Geenen JE, Howell DA. Endoscopic management of adenoma of the major duodenal papilla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:225-232. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bohnacker S, Seitz U, Nguyen D, Thonke F, Seewald S, deWeerth A, Ponnudurai R, Omar S, Soehendra N. Endoscopic resection of benign tumors of the duodenal papilla without and with intraductal growth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:551-560. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Nguyen N, Shah JN, Binmoeller KF. Outcomes of endoscopic papillectomy in elderly patients with ampullary adenoma or early carcinoma. Endoscopy. 2010;42:975-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Harano M, Ryozawa S, Iwano H, Taba K, Sen-Yo M, Sakaida I. Clinical impact of endoscopic papillectomy for benign-malignant borderline lesions of the major duodenal papilla. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:190-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y, Kobayashi G, Horaguchi J, Takasawa O, Obana T. Preoperative evaluation of ampullary neoplasm with EUS and transpapillary intraductal US: a prospective and histopathologically controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:740-747. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Binmoeller KF, Boaventura S, Ramsperger K, Soehendra N. Endoscopic snare excision of benign adenomas of the papilla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:127-131. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Kountouras J, Beltsis A, Papaziogas B, Mimidis K, Zavos C, Dimiropoulos S. Safety and long-term follow-up of endoscopic snare excision of ampullary adenomas. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:608-613. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Moriya T, Kimura W, Hirai I, Sakurai F, Isobe H, Ozawa K, Fuse A. Total papillectomy for borderline malignant tumor of papilla of Vater. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:859-861. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yoon SM, Kim MH, Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Lee TY, Kwon S, Oh HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Focal early stage cancer in ampullary adenoma: surgery or endoscopic papillectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:701-707. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Boix J, Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Moreno de Vega V, Domènech E, Gassull MA. Endoscopic resection of ampullary tumors: 12-year review of 21 cases. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Irani S, Arai A, Ayub K, Biehl T, Brandabur JJ, Dorer R, Gluck M, Jiranek G, Patterson D, Schembre D. Papillectomy for ampullary neoplasm: results of a single referral center over a 10-year period. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:923-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ito K, Fujita N, Noda Y. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of ampullary neoplasm (with video). Dig Endosc. 2011;23:113-117. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Heinzow HS, Lenz P, Lenze F, Domagk D, Domschke W, Meister T. Feasibility of snare papillectomy in ampulla of Vater tumors: meta-analysis and study results from a tertiary referral center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:332-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patel R, Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic ampullectomy: techniques and outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Herzog J, Eickhoff A. [Endoscopic therapy for tumours of the papilla of vater]. Zentralbl Chir. 2012;137:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Han J, Lee SK, Park DH, Choi JS, Lee SS, Seo DW, Kim MH. [Treatment outcome after endoscopic papillectomy of tumors of the major duodenal papilla]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:110-119. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pyun DK, Moon G, Han J, Kim MH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. A carcinoid tumor of the ampulla of Vater treated by endoscopic snare papillectomy. Korean J Intern Med. 2004;19:257-260. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Farrell RJ, Khan MI, Noonan N, O’Byrne K, Keeling PW. Endoscopic papillectomy: a novel approach to difficult cannulation. Gut. 1996;39:36-38. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ponchon T, Berger F, Chavaillon A, Bory R, Lambert R. Contribution of endoscopy to diagnosis and treatment of tumors of the ampulla of Vater. Cancer. 1989;64:161-167. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Han J, Kim MH. Endoscopic papillectomy for adenomas of the major duodenal papilla (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:292-301. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, Bedogni G. Endoscopic snare papillectomy in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis and ampullary adenoma. Endoscopy. 1997;29:685-688. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cheng CL, Sherman S, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Watkins JL, Fukushima T, Howard TJ, Lazzell-Pannell L, Lehman GA. Endoscopic snare papillectomy for tumors of the duodenal papillae. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:757-764. [PubMed] |

| 26. | García-Cano J, González-Martín JA. Bile duct cannulation: success rates for various ERCP techniques and devices at a single institution. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2006;69:261-267. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nakamura Y, Tajiri T, Uchida E, Aimoto T, Taniai N, Katsuno A, Cho K, Yoshida H. Adenoma of the minor papilla associated with pancreas divisum. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1841-1843. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Silvis SE. Endoscopic snare papillectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:205-207. [PubMed] |