Published online Jul 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4267

Revised: April 3, 2013

Accepted: April 10, 2013

Published online: July 14, 2013

Processing time: 162 Days and 7.7 Hours

A 57-year-old man underwent endoscopy for investigation of a duodenal polyp. Endoscopy revealed a hemispheric submucosal tumor, about 5 mm in diameter, in the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb. Endoscopic biopsy disclosed a neuroendocrine tumor histologically, therefore endoscopic mucosal resection was conducted. The tumor was effectively and evenly elevated after injection of a mixture of 0.2% hyaluronic acid and glycerol at a ratio of 1:1 into the submucosal layer. A small amount of indigo-carmine dye was also added for coloration of injection fluid. The lesion was completely resected en bloc with a snare after submucosal fluid injection. Immediately, muscle-fiber-like tissues were identified in the marginal area of the resected defect above the blue-colored layer, which suggested perforation. The defect was completely closed with a total of 9 endoclips, and no symptoms associated with peritonitis appeared thereafter. Histologically, the horizontal and vertical margins of the resected specimen were free of tumor and muscularis propria was also seen in the resected specimen. Generally, endoscopic mucosal resection is considered to be theoretically successful if the mucosal defect is colored blue. The blue layer in this case, however, had been created by unplanned injection into the subserosal rather than the submucosal layer.

Core tip: We herein report a case of endoscopic full-thickness resection of a duodenal neuroendocrine tumor after unplanned injection into the subserosal layer. Generally, large perforations require urgent salvage surgery and duodenal perforation is more serious than other sites of the gastrointestinal tract because of bile acid and pancreatic juice. In this case, we found the ‘‘mirror target sign’’ immediately, and repaired the defect endoscopically. Prompt recognition of this sign and rapid closing of the defect is important to minimize injury.

- Citation: Hatogai K, Oono Y, Fu KI, Odagaki T, Ikematsu H, Kojima T, Yano T, Kaneko K. Unexpected endoscopic full-thickness resection of a duodenal neuroendocrine tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(26): 4267-4270

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i26/4267.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4267

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) technique has been developed and widely performed to provide less invasive treatment for gastrointestinal tumors. However, perforation is perhaps one of the most unfavorable complications associated with EMR. The most effective way to avoid perforation is to maintain a sufficiently thick and long-lasting submucosal cushion by endoscopic fluid injection into the submucosal layer. Various solutions such as hypertonic saline, glycerin solution, and hyaluronic acid (HA) have been used, however, among those solutions, HA is preferred because of its higher viscosity[1]. Recently, EMR has been also applied for submucosal tumors, such as neuroendocrine tumors (NETs)[2-4]. We herein report a case of an endoscopic full-thickness resection of a duodenal NET after unplanned fluid injection into the subserosal layer.

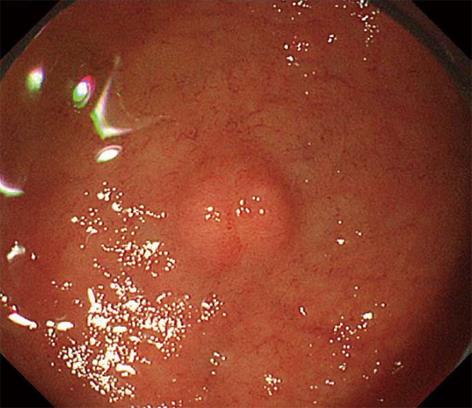

An asymptomatic 57-year-old man underwent endoscopy for investigation of a duodenal polyp detected in a private full medical checkup at another hospital. Endoscopy revealed a whitish hemispheric submucosal tumor with a smooth surface, about 5 mm in diameter, in the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb (Figure 1). Endoscopic biopsy disclosed a NET histologically. Because endoscopic findings such as size, shape, and mobility of the lesion indicated the tumor existed in the submucosal layer, EMR was conducted for its removal.

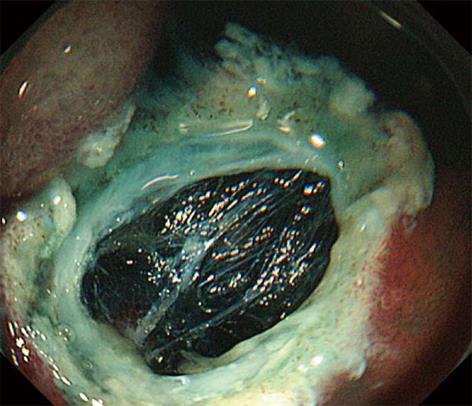

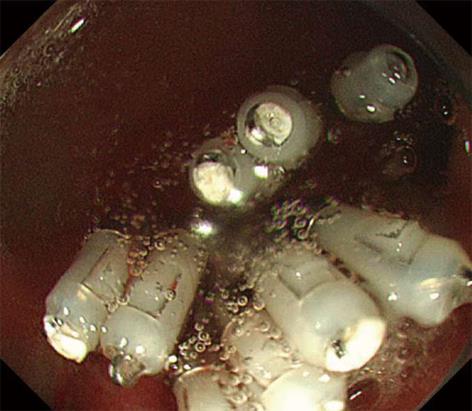

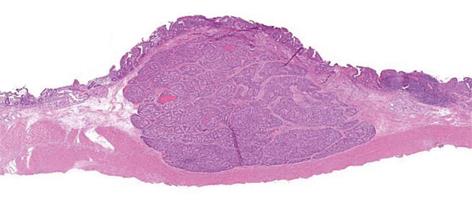

The tumor was effectively and evenly elevated after endoscopic submucosal injection of a mixture of 0.2% HA and glycerol at a ratio of 1:1 with a small amount of indigo-carmine dye added for coloration. The lesion was completely resected en bloc with a snare after submucosal fluid injection. Immediately, muscle-fiber-like tissues were identified at the margin of the resected defect, which suggested perforation, although a blue-colored layer was detected in the resection defect (Figure 2). The defect was completely closed with a total of 9 endoclips (Figure 3). No pneumoperitoneum was detected during or after EMR and endoscopic closure. The muscle layer was involved in the underside of the resected specimen (Figure 4). Computed tomography performed after the procedure revealed a small amount of free air but no fluid collection in the retroperitoneal space. Though the patient was in the hospital for 5 d longer than planned, he was successfully treated conservatively with intravenous fluids including antibiotics for 4 d without oral intake, and no symptoms associated with peritonitis appeared. Histologically, the tumor was diagnosed as a NET grade (G) 1 limited within the submucosal layer without muscular or lymphovascular invasion. The horizontal and vertical margins of the resected specimen were free of NET and the muscularis propria (MP) was also seen in the resected specimen (Figure 5). The blue layer in the resection defect had been created by fluid injection into the subserosal layer rather than the intended submucosal layer. No local recurrence or metastasis was detected after a follow-up of 30 mo from EMR.

Duodenal NETs account for 2%-15% of gastrointestinal NETs, which are the most common type of NETs[5,6]. Some of them secret bioactive substances such as serotonin, histamine, and prostaglandin, and cause the following typical clinical presentations: cutaneous flushing, sweating, and gut hypermotility with diarrhea[7]. The metastasis rate of duodenal NETs is associated with tumor size. Duodenal NETs, which are located outside the periampullary region, 1 cm or smaller in size, and confined to submucosal layer, are considered to be good candidates for endoscopic resection[5,8,9]. Endoscopic resection of duodenal NETs, however, can be associated with a higher risk of perforation, as the bowel wall is thinner in the duodenum and deeper endoscopic resection is necessary because of the tumor localization.

During EMR, a sufficiently thick submucosal elevation created by appropriate fluid injection into submucosal layer is crucial for prevention of perforation, and a small amount of indigo-carmine dye is commonly added for coloration of the injected solution to help determine whether the resection defect is in the submucosal layer or muscular layer (blue or white). In the present case, the tumor was elevated easily, evenly, and sufficiently after fluid injection as if the solution was appropriately injected into the submucosal layer. In addition, as the resection defect was colored blue after resection, we initially thought that EMR was successful. After careful investigation of the defect, however, we detected a few whitish bundles suggesting the presence of MP above the blue layer, a so-called “mirror target sign”. Therefore, we could recognize that the blue layer below the MP had been created by unplanned injection of fluid into the subserosal layer rather than the submucosal layer and concluded that our EMR had resulted in an unexpected full-thickness resection.

Both the “target sign” and “mirror target sign” were reported to help in identifying the endoscopic resection of the MP[10]. Surrounded by mucosa and submucosal tissue, the resected MP on the resected surface appears as the “target”. In contrast, the resected defect consisted of 2 concentric rings, the inner ring seen as an area of exposed subserosal layer and the outer ring as the commonly encountered submucosal layer, which make the mirror image of the target sign. A similar case has been reported in an EMR during colonoscopy[11]. A detailed examination of the resection defect is important, but endoscopists should remember that the blue layer in the resection defect of EMR is not always the submucosal layer as unexpected subserosal injection can occur. Especially when high viscosity fluid such as HA is used during EMR, unexpected subserosal injection would raise the MP and result in an unexpected full-thickness resection. Retrospectively, the vertical approach of fluid injection in the thin duodenal wall would also explain this unexpected subserosal injection. We suggest that the injection needle could easily be misguided into the subserosal layer, as duodenal submucosal tumors occupy a significant space of the thinner submucosal layer of the duodenum. Furthermore, the thinner duodenal MP could be easily elevated by subserosal injection.

Generally, large perforations require urgent salvage surgery. Duodenal perforation related to endoscopic treatment is reported to require salvage surgery in as many as 43.6% of cases, and these perforations are more serious than those occurring at other sites of the gastrointestinal tract because of bile acid and pancreatic juice[12]. However, selected cases, especially those that can be totally repaired endoscopically, can be managed medically. In this case, prompt recognition of the potential perforation led to the successful endoscopic closure of the defect with endoclips, and moreover, subserosal fluid injection of HA also may have played some important role in sealing the defect. We believe both the clips and the subserosal fluid injection protected this patient against subsequent peritonitis and salvage surgery.

In conclusion, we herein report a case of endoscopic full-thickness resection of a duodenal NET after unplanned fluid injection into the subserosal layer. In this case, we found the ‘‘mirror target sign’’ immediately and repaired the defect endoscopically. A detailed examination of the resection defect regardless of its color, prompt recognition of signs of possible inappropriate resection, and immediate closure of the defect are important to minimize injury.

P- Reviewers Conte D, Oberg KE, Siriwardana HPP, Vitale G S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kashimura K, Mizushima Y, Oka M, Enomoto S, Kakushima N, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Iguchi M. Comparison of various submucosal injection solutions for maintaining mucosal elevation during endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2004;36:579-583. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yoshikane H, Goto H, Niwa Y, Matsui M, Ohashi S, Suzuki T, Hamajima E, Hayakawa T. Endoscopic resection of small duodenal carcinoid tumors with strip biopsy technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:466-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Higaki S, Nishiaki M, Mitani N, Yanai H, Tada M, Okita K. Effectiveness of local endoscopic resection of rectal carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 1997;29:171-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ichikawa J, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Kida Y, Imaizumi H, Kida M, Saigenji K, Mitomi H. Endoscopic mucosal resection in the management of gastric carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2003;35:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dalenbäck J, Havel G. Local endoscopic removal of duodenal carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2004;36:651-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1587-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717-1751. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Scherübl H, Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Management of early gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoshikane H, Tsukamoto Y, Niwa Y, Goto H, Hase S, Mizutani K, Nakamura T. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: evaluation with endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:375-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Swan MP, Bourke MJ, Moss A, Williams SJ, Hopper A, Metz A. The target sign: an endoscopic marker for the resection of the muscularis propria and potential perforation during colonic endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Konuma H, Fu KI, Konuma I, Ueyama H, Takahashi T, Ogura K, Miyazaki A, Watanabe S. Endoscopic full-thickness resection of a lateral spreading rectal tumor after unplanned injection of dilute hyaluronic acid into the subserosal layer (with video). Tech Coloproctol. 2012;16:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Machado NO. Management of duodenal perforation post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. When and whom to operate and what factors determine the outcome A review article. JOP. 2012;13:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |