Published online Jul 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4185

Revised: May 1, 2013

Accepted: May 17, 2013

Published online: July 14, 2013

Processing time: 171 Days and 18.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes of cap polyposis in the pediatric population.

METHODS: All pediatric patients with histologically proven diagnosis of cap polyposis were identified from our endoscopy and histology database over a 12 year period from 2000-2012 at our tertiary pediatric center, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Singapore. The case records of these patients were retrospectively reviewed. The demographics, clinical course, laboratory results, endoscopic and histopathological features, treatments, and outcomes were analyzed. The study protocol was approved by the hospital institutional review board. The histological slides were reviewed by a pediatric histopathologist to confirm the diagnosis of cap polyposis.

RESULTS: Eleven patients were diagnosed with cap polyposis. The median patient age was 13 years (range 5-17 years); the sample included 7 males and 4 females. All of the patients presented with bloody stools. Seven patients (63%) had constipation, while 4 patients (36%) had diarrhea. All of the patients underwent colonoscopy and polypectomies (excluding 1 patient who refused polypectomy). The macroscopic findings were of polypoid lesions covered by fibrinopurulent exudates with normal intervening mucosa. The rectum was the most common involvement site (n = 9, 82%), followed by the rectosigmoid colon (n = 3, 18%). Five (45%) patients had fewer than 5 polyps, and 6 patients (65%) had multiple polyps. Histological examination of these polyps showed surface ulcerations with a cap of fibrin inflammatory exudate. Four (80%) patients with fewer than 5 polyps had complete resolution of symptoms following the polypectomy. One patient who did not consent to the polypectomy had resolution of symptoms after being treated with sulphasalazine. All 6 patients with multiple polyps experienced recurrence of bloody stools on follow-up (mean = 28 mo).

CONCLUSION: Cap polyposis is a rare and under-recognised cause of rectal bleeding in children. Our study has characterized the disease phenotype and treatment outcomes in a pediatric cohort.

Core tip: Cap polyposis is a rare and under-recognized condition with distinct clinical, endoscopic and histopathological features. All children with cap polyposis invariably present with rectal bleeding. Awareness of this diagnosis is important as its clinical and endoscopic features can mimic inflammatory bowel disease resulting in prolonged and inappropriate treatment. This article evaluates the clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes in a series of children with cap polyposis. Complete polypectomy should be performed where possible in combination with medical therapy. Prognosis is good for children with few polyps although recurrence rate is high in those with multiple polyps at diagnosis requiring further surgical intervention.

- Citation: Li JH, Leong MY, Phua KB, Low Y, Kader A, Logarajah V, Ong LY, Chua JH, Ong C. Cap polyposis: A rare cause of rectal bleeding in children. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(26): 4185-4191

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i26/4185.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4185

Cap polyposis (CP) is a rare and under-recognized condition with distinct clinical, endoscopic and histopathological features. It was first described by Williams et al[1] in 1985. CP is characterized by inflammatory polyps that are usually located from the rectum to the distal descending colon. Histologically, these polyps consist of elongated, tortuous, and often distended crypts covered by a “cap” of inflammatory granulation tissues. Macroscopic findings include dark red, sessile polyps that are commonly situated on the apices of transverse mucosal folds, with normal intervening mucosa.

Characteristic symptoms in adults include mucous diarrhea, tenesmus and rectal bleeding[2]. CP may be confused with other inflammatory conditions of the large intestine, in particular inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), due to their similarities in clinical and endoscopic features. The pathogenesis of CP is unknown, and no specific treatment has yet been established.

CP has been rarely described in the pediatric population. We report a case series of 11 pediatric patients diagnosed with CP and characterized their clinical, endoscopic, and histological features.

All pediatric patients with histologically proven diagnosis of CP were identified from our endoscopy (total number = 1905) and histology database over a 12 year period from 2000-2012 at our tertiary pediatric center, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Singapore. The case records of these patients were retrospectively reviewed. The demographics, clinical course, laboratory results, endoscopic and histopathological features, treatments, and outcomes were analyzed. The study protocol was approved by the hospital institutional review board (Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board). The histological slides were reviewed by a pediatric histopathologist to confirm the diagnosis of CP.

There were 11 pediatric patients diagnosed with cap polyposis from 2000 and 2012. The clinical features of these patients are summarized in Table 1. There were 7 males and 4 females, with a median age of 13 years (range 5-17 years). The racial distributions included 5 Malays, 4 Chinese, and 2 Indian patients.

| ID | Age (yr) | Sex | Diarrhea | C + S | Abdo pain | PR bleeding | No. of polyps | Site | Antibiotics | Stool softeners | Recur | Follow up (mo) |

| 1 | 5 | M | No | No | No | Yes | 1 | R | No | Yes | No | 24 |

| 2 | 13 | M | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 | R | No | Yes | No | 4 |

| 3 | 8 | M | NA | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | R | No | Yes | No | 3 |

| 4 | 8 | M | No | Yes | No | Yes | 1 | R | Metro | No | No | 3 |

| 5 | 15 | F | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 | R | No | No | No | 24 |

| 6 | 15 | M | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | n > 5 | R | Metro | Yes | Yes | 36 |

| 7 | 10 | M | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | n > 5 | R | Metro | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| 8 | 11 | F | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | n > 5 | R | Metro | Yes | Yes | 72 |

| 9 | 13 | F | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | n > 5 | R | No | Yes | Yes | 72 |

| 10 | 14 | F | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | n > 5 | R + S | No | Yes | Yes | 36 |

| 11 | 17 | M | Yes | No | No | Yes | n > 5 | R + S | No | Yes | NA | Lost |

| Mean = 28 |

Common presenting features of these patients included per-rectal bleeding, constipation and straining, diarrhea, and abdominal pain (Table 1). All 11 patients presented with blood in the stools. Seven patients (63%) had constipation and/or straining, and 4 patients (36%) had diarrhea. Abdominal pain was a presenting complaint in 6 (54%) patients. Digital rectal examinations revealed rectal polypoid masses in 7 (63%) patients and 1 patient had perianal fissure.

The median hematological values at diagnosis were hemoglobin 10.9 (IQR 12.6-14) g/dL, white cell counts 6.7 × 109/L (IQR 4-11)109/L and platelet counts of 342 (IQR 150-400 ) × 1000/μL. All of the patients had normal coagulation profiles. Eight of the 11 patients had normal serum albumin measured with a median value of 38 g/L (IQR 35-45). Only 2 patients (IDs 8 and 10) had hypoalbuminemia. Inflammatory markers C-Reactive protein/Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate were measured in 6 patients (ID 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 10), and they were normal.

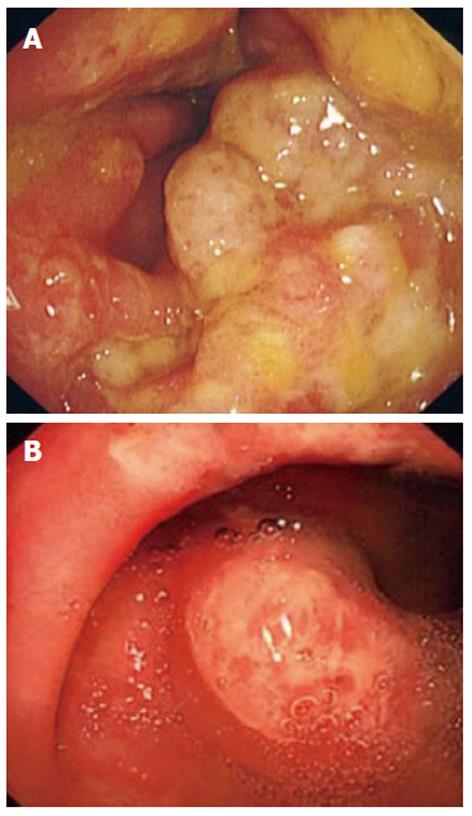

All patients underwent colonoscopy with macroscopic findings of polyps or polypoid lesions. These were mainly small, red and sessile polyps covered by a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates predominantly found on the apices of the mucosa folds. The intervening mucosa was normal both macroscopically and on histological examination (Figure 1A and B). The polyps were most commonly located in the rectum only (n = 9, 82%). Two patients (18%) had polyps in the rectum and sigmoid colon. The number of polyps ranged from 1 to more than 10. Five (45%) patients had fewer than 5 polyps, and 6 (65%) patients had multiple (> 5) polyps on initial colonoscopy.

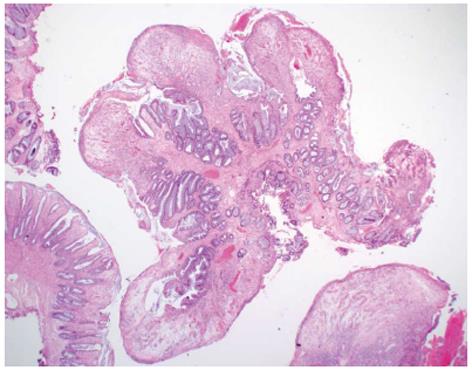

On histological examination, these colonic polyps showed a variable degree of surface ulceration associated with a cap of fibrin inflammatory exudates and granulation tissue. Focally, the surface epithelium is preserved but attenuated. The crypts within the polyps showed crypt elongation and luminal epithelial serration. In some cases, the crypts were mildly distended towards the surface. The lamina propria contained a variably increased number of acute and chronic inflammatory cells (Figure 2). These histological features were consistent with inflammatory cap polyps. The mucosa surrounding these polyps was normal.

Three patients presented with abdominal pain and underwent simultaneous upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies; the histological findings showed mild gastritis but no evidence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori). There were no polypoid lesions noted in the stomach of these 3 patients.

All but one patient underwent polypectomies. Patients 1-5 had fewer than 5 polyps detected by the initial colonoscopy. Patients 1-4 had polypectomy performed and were subsequently treated with stool softeners. Patient 4 also received a course of metronidazole. All 4 of these patients had complete resolution of their symptoms with no further rectal bleeding at mean follow-up period of 28 mo. Patient 5 had 3 small sessile polyps and did not consent for polypectomy but had complete resolution of symptoms at 18 mo after being treated with sulphasalazine.

Six patients with multiple polyps (Patients 6-11) underwent colonoscopy and polypectomies. One patient was lost to follow-up (Patient 11). The other 5 patients were given stool softeners and 3 patients were given metronidazole. All of the patients experienced a recurrence of symptoms, mainly blood in the stools at subsequent follow-up (mean follow-up period of 28 mo). These patients required repeated colonoscopies with polypectomies and continued to have intermittent per rectal bleeding. Patient 8 eventually had a resolution of his symptoms after 6 colonoscopies with multiple polypectomies at follow-up of 6 years. Patient 11, whose polyps were confined to the recto-sigmoid area, had persistent rectal bleeding that required recurrent blood transfusions and will require more extensive surgical resection in the future. All of the 5 patients with multiple polyps were otherwise well-thrived and had normal inflammatory markers at subsequent follow-up.

CP is a rare but distinct disorder with characteristic endoscopic and histological features first described by Williams[1]. Although CP was first described more than 20 years ago, this disease is still not well recognized by physicians. Only approximately 60 cases have been reported in the English language medical literature, mainly as case series or case reports. Due to its rarity, CP is often under-recognized and misdiagnosed as inflammatory bowel disease IBD, leading to prolonged and inappropriate treatment.

To our knowledge, this report is the first and largest case series describing CP in the pediatric population. Shimuzu et al[3] have previously described CP in a 12 year old girl. Previous adult studies have found that CP occurs more frequently in females than males[3]. In contrast, there were more boys than girls (7 males and 4 females) in our study, and their median age was 13 years old. We also noted a slightly higher proportion of Malay patients (approximately 40%) in our cohort.

Common presenting symptoms of previously described cases of CP include mucous and/or bloody diarrhea, habitual straining with defecation, chronic constipation and abdominal pain[4]. Rectal bleeding occurred universally in all 11 patients in our study. In total, 65% of our patients had chronic straining and/or constipation, while 35% of the patients had diarrhea. Almost half of our patients presented with abdominal pain, particularly those with multiple polyps. Anemia was a predominant feature in our cohort, with median Hb of 10.9 g/dL.

Protein-losing enteropathy has been reported to be associated with CP[5-9]. Shiomi et al[9] reported a case of CP in which protein loss from the lesions was confirmed via technetium 99m-labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid complexed to human serum albumin. There have also been reports of lower limb edema resulting from protein-losing enteropathy from CP[5,7-10]. In addition, laboratory investigations often reveal low total protein and serum albumin levels in CP patients. Symptoms of pre-tibial edema and low protein levels have been shown to normalize with resolution of cap polyposis[5,6-9]. None of the patients in our study presented with lower limb edema. Moreover, hypoalbuminemia was not a predominant feature in our cohort, with only 2 patients having documented low albumin levels.

CP is characterized by polyps covered with fibrinopurulent exudates on the surface. The polyps range in size from several millimeters to as large as 7 cm[11,12]. The number of polyps varies from 1 to a few hundred, and the polyps are typically located at the apices of mucosal folds. These polyps have varying morphologies, including polypoid, ulcerative, and flat types[13]. The intervening mucosa has been described as normal or covered with white specks[13], although the significance of this morphology has yet to be ascertained. Initial edematous, flushed mucosa with subsequent development of polyps at the same area, has been reported with serial endoscopic studies[7,14]. The rectum and rectosigmoid colon are the most commonly affected sites, although pan-colonic and gastric involvement has been described[4,6,15]. In agreement with previous findings, all patients in our series had polyps localized to the rectum or rectosigmoid region with normal intervening mucosa.

Histologically, cap polyps consist of elongated, tortuous and hyperplastic crypts that are attenuated towards the mucosal surface. The surfaces of these polyps are ulcerated and covered by a thick layer of fibrinopurulent exudates, hence the term “cap polyps”. The lamina propria also contain inflammatory cells[5]. These histological features were reported in our patients.

The exact etiology and pathogenesis of inflammatory cap polyps are unclear. Various possible causes, including infection[6,14], mucosal ischemia[2], inflammation[16], abnormal bowel motility, and repeated trauma to the colonic mucosa caused by straining[8] have been proposed. Campbell et al[2] proposed that abnormal colonic motility may lead to prolapse of redundant mucosa at the apices of transverse mucosal folds. The resultant local ischemia produces characteristic histological appearances of fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria; superficial erosion associated with granulation tissue; and elongated, tortuous, hyperplastic glands. These histological features are also present in other conditions, such as prolapsing mucosal polyps, solitary rectal ulcers, inflammatory cloacogenic polyps, and gastric antral vascular ectasia. These findings, along with the fact that CP predominantly affects the rectosigmoid and has a circumferential involvement of the colonic mucosa, have led many researchers to attribute CP to abnormal colonic motility and repeated trauma to the colonic mucosa caused by straining during defecation. Hence, CP has been considered part of a spectrum of “mucosal prolapse syndromes”[5,17,18].

However, aberrant motility of the distal large bowel may only partially contribute to the development of cap polyposis. Although many CP patients present with a history of straining at defecation, these individuals usually lack a typical mucosal prolapse that involves the anterior wall of the lower rectum[18]. There have also been reports of CP developing in patients without evidence or history of abnormal colonic motility. Géhénot et al[14] and Konishi et al[16] reported the differentiating features between and mucosal prolapse syndrome, where there was significant thickening of the second layer on endoscopic ultrasound in cap polyposis, as opposed to smooth, diffuse thickening of the third layer and minimal thickening of the second layer in mucosal prolapse. Furthermore, avoidance of straining alone has not been reported as an effective treatment modality. In our cohort of patients, stool softeners were prescribed in 8 of 11 patients to avoid straining on defaecation but the symptoms still recurred in those with multiple polyps.

In recent years, the role of infectious organisms, such as H. pylori[5,6,7,19,20], and inflammation[14] has been proposed. Three of our patients underwent an upper GI endoscopy, but none of them showed any evidence of H. pylori on in their gastric mucosa biopsies.

Konishi et al[21] described a patient in whom CP was noted to progress along the surgical anastomotic line after a laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy was performed, leading to the hypothesis that local inflammation plays a role in the development of cap polyposis. The effectiveness of infliximab in 2 case reports[22,23] also supports the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of CP. However, molecular studies of the abnormal mucus in CP have proven inconclusive. Buisine et al[24] found a predominance of non-sulphated mucins in cap polyps, compared to both non-sulphated and sulphated mucins expressed in normal colonic mucosa. This finding has been associated with a wide range of pathological conditions, including colorectal carcinomas, ulcerative colitis, and familial polyposis, and there has been a lack of data to show a direct involvement of mucins in the initial pathogenesis of cap polyposis.

Different treatment modalities have been trialed including steroids, aminosalicylates, infliximab, H. pylori eradication, endoscopic and surgical resection with variable clinical outcomes. The clinical course of CP has been reported to range from spontaneous remission[19,22] to a disease course requiring surgical resection of the affected bowel segments.

Metronidazole has been used widely in the treatment of CP, often in combination with other modalities[5,7,8,25-27]. Shimizu et al[3] reported improvement of symptoms and stromal infiltration on colonic biopsies in a patient treated with metronidazole after failed treatment with mesalamine and levofloxacin, leading to the hypothesis that the role of metronidazole may be related to its anti-inflammatory effects rather than antibiotic action against specific pathogens. It has been postulated that by acting as a radical scavenger, metronidazole can inhibit leukocyte emigration and adherence[5]. In our series, 4 patients received a course of metronidazole together with polypectomy. Of these 4 patients, 3 patients had a recurrence of symptoms. This result suggests that metronidazole may have a limited role in the treatment of patients who have multiple cap polyps.

Limited reports of treatment with infliximab have yielded varying results[22,23,28]. Kim et al[26] reported a resolution of symptoms and endoscopic lesions after a single infusion of infliximab, but Maunory et al[27] reported a case of recurrence despite 2 infusions of infliximab.

The effective eradication of H. pylori has been reported to play a role in the treatment of CP. A review of the English language medical literature has identified 6 reports[6,7,15,19,20,25] in which 9 CP patients were treated with H. pylori eradication treatment, 8 of whom showed a complete resolution of symptoms and cap polyps (88.9%) and 1 patient experienced a partial improvement of symptoms. Interestingly, all 9 patients tested positive for H. pylori, and the patient who showed only a partial improvement in symptoms had persistent H. pylori infection despite eradication therapy.

The possible role of H. pylori in extragastric diseases, including idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, iron deficiency anemia, chronic urticaria and ischemic heart disease, has been suggested[28-30]. Various mechanisms, including the release of inflammatory mediators, molecular mimicry and a systemic immune response, have been postulated[20]. Although H. pylori has not been detected in the colonic mucosae of CP patients, these results suggest that H. pylori infection may indirectly play a part in the etiology of CP. Similar histological features between Menetrier’s disease (in which H. pylori has been postulated to play a role) and CP, such as elongated tortuous crypts, have been highlighted by Akamatsu et al[7]. Testing for H. pylori in all CP cases and subsequent eradication therapy, if necessary, has been recommended by various authors[7,20]. In our series of pediatric patients, 3 patients underwent upper endoscopy, but none of these patients had H. pylori detected in their gastric mucosal biopsies. One patient received triple therapy but continued to have recurrence of symptoms. The role of H. pylori eradication therapy needs to be further evaluated in the pediatric population.

Steroids and aminosalicylates have been used with varying results[8,25]. Chang et al[25] reported a series of 7 patients, 2 of whom maintained clinical response after 2 courses of systemic steroids: Symptoms persisted in 1 patient despite 2 courses of steroids and aminosalicylates; 3 patients experienced spontaneous remission, and 1 patient showed partial improvement after H. pylori eradication therapy. None of our patients received steroid therapy, although one patient was successfully treated with aminosalicylic acid. All of our patients for whom inflammatory markers were measured had normal values for these markers.

Polypectomy and surgical removal of the affected colon have produced inconsistent results, with Ng et al[4] reporting recurrence in 2 of 5 patients receiving polypectomy and recurrence in 2 of 4 patients who underwent surgical resection of the affected colon[7,31]. In our series, 10 of 11 patients underwent polypectomies. However, only half of these patients achieved complete remission at mean follow-up of 28 mo. These were patients with fewer than 5 polyps at presentation. Those patients with persistent symptoms despite polypectomies were more likely to have multiple polyps at presentation.

The clinical course and long-term prognosis of CP remain largely unknown. A self-limiting course has been reported, despite whether polypectomy or surgery has been performed[32,33]. A polypectomy will, however, provide a definitive histological diagnosis and may also be warranted when the patient presents with significant lower gastrointestinal bleeding. A complete polypectomy was effective in several studies[4,5], and this approach is recommended whenever possible. Our findings suggest that patients with multiple polyps at diagnosis are more likely to experience symptom recurrence.

In conclusion, CP is a rare cause of rectal bleeding in children. Awareness of this diagnosis is important as the clinical and endoscopic features of CP can mimic Inflammatory Bowel Disease[32] and a misdiagnosis can result in prolonged and inappropriate treatment. CP polyps are distinctive inflammatory polyps covered by a cap of fibrinopurulent exudates normally located at the apices of the mucosal folds with normal intervening mucosa both macroscopically and on histological examination. Although the pseudopolyps in IBD have granulation tissues, the intervening mucosa is usually associated with inflammatory changes, such as superficial ulcerations, granularity and/or friability with crypt abscesses[34]. CP is mainly localized to the rectum and sigmoid, whereas the pseudopolyps in IBD may involve the entire colon. Clinically, CP patients are also more likely to have normal inflammatory markers with no extraintestinal manifestations, such as weight loss, oral ulcers, joint pain etc.

The clinical course of CP has not been well described. CP may in some instances, be a self-limiting condition. A complete colonoscopy should be performed as polyps have been described throughout the colon[35,36] when possible, a total polypectomy is recommended. Patients with predominant straining/constipation symptoms can be treated with laxatives and advised to avoid straining. Medical treatment including antibiotics (e.g., metronidazole) and eradication therapy for H. pylori has been shown to be effective in some reports. There is currently no good evidence for using aminosalicylic acid or immunosuppressive therapy for treatment of CP. Surgical resection may be indicated if symptoms persist despite medical therapy, although recurrence has been described post-operatively.

In summary, CP is a rare cause of rectal bleeding in children. Awareness of this diagnosis is important as its clinical and endoscopic features can mimic inflammatory bowel disease and a misdiagnosis can result in prolonged and inappropriate treatment. Response to medical treatment has been shown to be inconsistent and unsatisfactory. Endoscopic or surgical excision can be curative, but the recurrence rates are high, particularly if numerous polyps are present. Longer term studies are necessary to understand the natural course of this condition.

Cap polyposis (CP) is a rare and under-recognized condition with distinct clinical, endoscopic and histopathological features first described by Williams et al. Little is known of CP in the pediatric population.

The pathogenesis of CP is unknown and no specific treatment has been established. CP has been rarely described in the paediatric population. The research hotspot is to better define the clinical features and course of CP in children, and identify effective treatment modalities.

The study is the first case series in available literature to characterise the disease phenotypes and treatment outcomes in a group of paediatric patients.

Cap polyposis is a rare condition especially in children. It is commonly misdiagnosed as inflammatory bowel disease subjecting patients to unnecessary immunosuppressive therapy. The clinical course and long-term prognosis of cap polyposis remain largely unknown. A case series describing the treatment modalities and clinical course of CP in children will raise the awareness of this rare condition amongst paediatricians and gastroenterologists, as well as improve treatment outcomes.

Cap polyposis is characterised by inflammatory polyps located in the rectum to distal descending colon. Histologically, these polyps consist of elongated, tortuous crypts covered by a “cap” of inflammatory granulation tissue.

The manuscript is interesting and the main importance of the research is represented by the help offered to clinicians and endoscopists in recognizing and treating a rare pathology that could be misdiagnosed as Inflammatory Bowel Disease. These series of children demonstrate the importance of cap polyposis in young patients. Manuscript is well presented and well written.

P- Reviewers Bian ZX, Guglielmi FW, Gravante G, Nash GF S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Williams GT, Bussey HR, Morson BC. Inflammatory “cap” polyps of the large intestine. Br J Surg. 1985;72:S133. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Campbell AP, Cobb CA, Chapman RW, Kettlewell M, Hoang P, Haot BJ, Jewell DP. Cap polyposis--an unusual cause of diarrhoea. Gut. 1993;34:562-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shimizu K, Koga H, Iida M, Yao T, Hirakawa K, Hoshika K, Mikami Y, Haruma K. Does metronidazole cure cap polyposis by its antiinflammatory actions instead of by its antibiotic action A case study. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1465-1468. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ng KH, Mathur P, Kumarasinghe MP, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Cap polyposis: further experience and review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1208-1215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gallegos M, Lau C, Bradly DP, Blanco L, Keshavarzian A, Jakate SM. Cap polyposis with protein-losing enteropathy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:415-420. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Oiya H, Okawa K, Aoki T, Nebiki H, Inoue T. Cap polyposis cured by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Akamatsu T, Nakamura N, Kawamura Y, Shinji A, Tateiwa N, Ochi Y, Katsuyama T, Kiyosawa K. Possible relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and cap polyposis of the colon. Helicobacter. 2004;9:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oriuchi T, Kinouchi Y, Kimura M, Hiwatashi N, Hayakawa T, Watanabe H, Yamada S, Nishihira T, Ohtsuki S, Toyota T. Successful treatment of cap polyposis by avoidance of intraluminal trauma: clues to pathogenesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2095-2098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shiomi S, Moriyama Y, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Kuroki T, Kawabe J, Ochi H, Okuyama C. A case of cap polyposis investigated by scintigraphy with human serum albumin labeled with Tc-99m DTPA. Clin Nucl Med. 1998;23:521-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oshitani N, Moriyama Y, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi K, Kitano A. Protein-losing enteropathy from cap polyposis. Lancet. 1995;346:1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Obusez EC, Liu X, Shen B. Large pedunculated inflammatory cap polyp in an ileal pouch causing intermittent dyschezia. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e308-e309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kajihara H, Uno Y, Ying H, Tanaka M, Munakata A. Features of cap polyposis by magnifying colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:775-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi H, Yao T, Nakamura S, Mizuno M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Cap polyposis of the colon and rectum: an analysis of endoscopic findings. Endoscopy. 2001;33:262-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Géhénot M, Colombel JF, Wolschies E, Quandalle P, Gower P, Lecomte-Houcke M, Van Kruiningen H, Cortot A. Cap polyposis occurring in the postoperative course of pelvic surgery. Gut. 1994;35:1670-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang SY, Choi SI. Can the stomach be a target of cap polyposis. Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E124-E125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Takei Y, Kojima T, Nagawa H. Cap polyposis: an inflammatory disorder or a spectrum of mucosal prolapse syndrome. Gut. 2005;54:1342-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tendler DA, Aboudola S, Zacks JF, O’Brien MJ, Kelly CP. Prolapsing mucosal polyps: an underrecognized form of colonic polyp--a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:370-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tomiyama R, Kinjo F, Kinjo N, Nakachi N, Kawane M, Hokama A. Gastrointestinal: cap polyposis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:741. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Takeshima F, Senoo T, Matsushima K, Akazawa Y, Yamaguchi N, Shiozawa K, Ohnita K, Ichikawa T, Isomoto H, Nakao K. Successful management of cap polyposis with eradication of Helicobacter pylori relapsing 15 years after remission on steroid therapy. Intern Med. 2012;51:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nakagawa Y, Nagai T, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Tasaki T, Soma W, Hisamatsu A, Watada M, Murakami K, Fujioka T. Cap polyposis (CP) which relapsed after remission by avoiding straining at defecation, and was cured by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Intern Med. 2009;48:2009-2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Takei Y, Kojima T, Nagawa H. Confined progression of cap polyposis along the anastomotic line, implicating the role of inflammatory responses in the pathogenesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:446-47; discussion 447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jang LL, Kim KJ, Chang HK, Park MJ, Kim JB, Lee JS, Kang SJ, Tag HS. Low rectal mass diagnosed as a cap polyp. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2011;22:111-113. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Bookman ID, Redston MS, Greenberg GR. Successful treatment of cap polyposis with infliximab. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1868-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Buisine MP, Colombel JF, Lecomte-Houcke M, Gower P, Aubert JP, Porchet N, Janin A. Abnormal mucus in cap polyposis. Gut. 1998;42:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chang HS, Yang SK, Kim MJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Kim JH. Long-term outcome of cap polyposis, with special reference to the effects of steroid therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim ES, Jeen YT, Keum B, Seo YS, Chun HJ, Um SH, Kim CD, Ryu HS. Remission of cap polyposis maintained for more than three years after infliximab treatment. Gut Liver. 2009;3:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Maunoury V, Breisse M, Desreumaux P, Gambiez L, Colombel JF. Infliximab failure in cap polyposis. Gut. 2005;54:313-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Franceschi F, Gasbarrini A. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;21:325-334. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Di Campli C, Gasbarrini A, Nucera E, Franceschi F, Ojetti V, Sanz Torre E, Schiavino D, Pola P, Patriarca G, Gasbarrini G. Beneficial effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on idiopathic chronic urticaria. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1226-1229. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F. Does H. Pylori infection play a role in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and in other autoimmune diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1271-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Akamatsu T, Yokoyama T, Nakamura N, Ochi Y, Saegusa H, Kawamura Y, Takayama M, Kiyosawa K, Igarashi T. [Endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding peptic ulcers]. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2003;92:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tamura S, Onishi S, Ohkawauchi K, Miyamoto T, Ueda H. A case of “cap polyposis”-like lesion associated with ulcerative colitis: is this a case of cap polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3311-3312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ohkawara T, Kato M, Nakagawa S, Nakamura M, Takei M, Komatsu Y, Shimizu Y, Takeda H, Sugiyama T, Asaka M. Spontaneous resolution of cap polyposis: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:599-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sawczenko A, Sandhu BK. Presenting features of inflammatory bowel disease in Great Britain and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:995-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Sadamoto Y, Jimi S, Harada N, Sakai K, Minoda S, Kohno S, Nawata H. Asymptomatic cap polyposis from the sigmoid colon to the cecum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:654-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Isomoto H, Urata M, Nakagoe T, Sawai T, Nomoto T, Oda H, Nomura N, Takeshima F, Mizuta Y, Murase K. Proximal extension of cap polyposis confirmed by colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:388-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |