CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old female patient was admitted to our department. She complained of slight intermittent chest pain and dyspnea on exertion for approximately 20 d associated with poor appetite and weight loss. A mass was present in her epigastrium and right hypochondrium. She has lived in a region in which schistosomiasis is epidemic and has had well-controlled hypertension with regular anti-hypertensive therapy for the last five years. She suffered rib fractures and liver rupture in a traffic accident 39 years ago and recovered post-laparotomy. Her general examination and laboratory parameters, including liver function tests, were within the normal limits. Upon abdominal examination, a large-sized vertical midline incision scar was identified, and a mass with restricted mobility and a smooth surface was palpable. Hepatic ultrasonography showed a round mass (20.3 cm × 17.3 cm × 16.0 cm in size) with fluid echogenicity in the right lobe of her liver. A hepatic cystic-solid mass (19.7 cm × 18.5 cm × 15.6 cm in size) was identified with the aid of an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1). Liver textiloma was highly suspected.

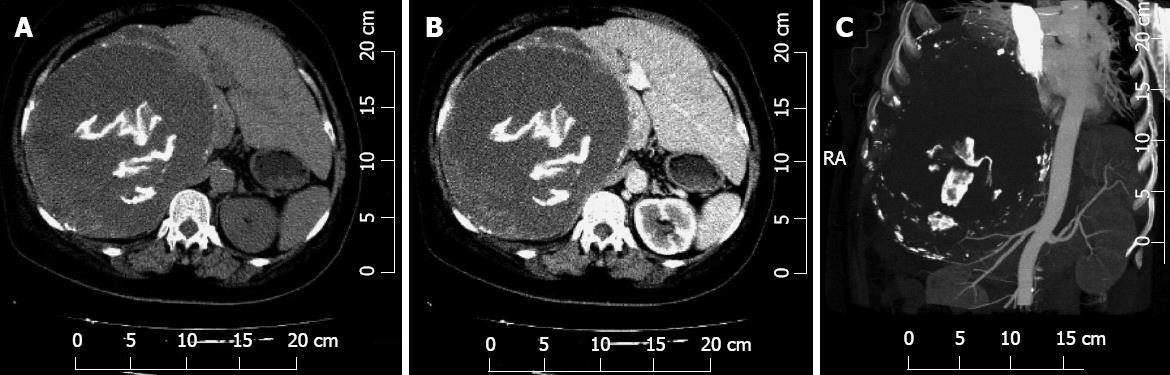

Figure 1 Computed tomography images of the abdomino-thoracic region showing a cystic mass in the liver with filiform calcification inside and a small amount of pleural effusion.

A: Plain; B: Contrast-enhanced; C: Reconstructive. RA: Right anterior.

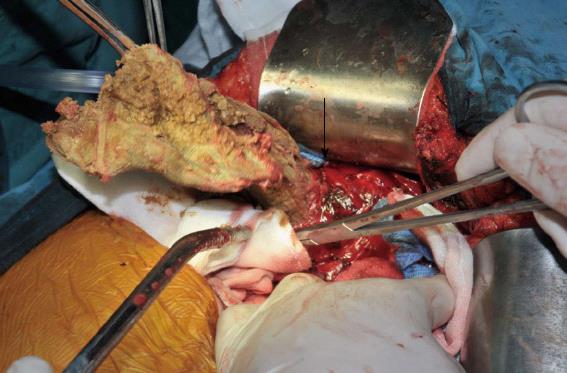

The patient was scheduled for an exploratory laparotomy under general anesthesia. After the abdomen was opened, a very large cyst was found in the right lobe of her liver protruding into the right chest cavity. All appropriate precautions were taken to prevent the cyst from rupturing. Thin, brown pus was suctioned after anhydrous alcohol was repeatedly infused into the cyst, and several pieces of gauze were found after the cyst was opened (Figure 2). Pus samples were collected in sterile syringes and sent for culture and sensitivity analyses. The surgical gauze was removed, and peritoneal lavage was performed. A double-lumen tube was used to drain the remaining fluid in the cyst and another rubber tube was inserted in hepatorenal recess. The abdomen was then closed after obtaining exact counts of sponges and instruments and taking all necessary precautions.

Figure 2 Surgical gauze (arrow) and the cyst wall (held with vessel forceps) in the right liver lobe following the evacuation of pus.

The culture of the pus was sterile. The histological analysis documented gauze remnants with necrotic material inclusions and a fibrotic capsule with old, calcified schistosome eggs that was attached to the foreign body granuloma. The postoperative period was uneventful; the patient was discharged with the double-lumen drainage tube in place and advised to return for follow-up visits. The double-lumen tube was extracted two months later, and the patient now lives a normal life.

DISCUSSION

Foreign bodies may be introduced into the liver via penetrating trauma, surgical procedures or the ingestion of foreign bodies (which later migrate from the gut). Thus, these foreign bodies can be classified into the following three categories: penetrating, medical and migrated foreign bodies.

Penetrating foreign bodies

Penetrating foreign bodies, such as bullets, shell fragments, glass and wood, can become lodged in the liver via gunshot or stab wounds[2-7]. Although gunshot or stab injuries may not introduce penetrating foreign bodies into the liver[2,3], they remain the most common causes. An immediate assessment with ultrasound or CT after a blunt or penetrating abdominal injury remains the gold standard method for identifying bleeding and foreign bodies[4]. Liver is the most commonly injured solid organ in blunt or penetrating abdominal or thoracic trauma, however, liver wounds associated with penetrating foreign bodies that are retained in the liver are rare[5]. Botoi et al[6] reported six cases of liver shotgun wounds that all resulted in metal foreign bodies being retained in the liver. The patients were all male, and most were young. Hunting rifles were involved in three of the cases. The wounds were complex in five of the six cases, and most of the injuries affected the right liver lobe. Hepatectomy was used in 40% of the cases[6]. Hepatic penetrating foreign bodies are surgical emergencies that should prompt prophylactic extraction through laparotomy; however, the tissue injury caused by the penetrating liver trauma and not the penetrating foreign bodies themselves require surgery[4,5]. Some penetrating foreign bodies, such as bullets, produce no clinical symptoms for many years.

Laparotomy remains the standard treatment for penetrating organ injuries with retained foreign bodies; however, non-operative management[7] is preferred for stable patients, especially those with penetrating organ injuries without retained foreign bodies. In the appropriate trauma center environment, selective non-operative management of penetrating abdominal solid organ injuries, especially liver injuries, has a high success rate and a low complication rate. Even high-grade liver injuries do not preclude non-operative management[8].

Major complex surgical procedures, such as an anatomical resection, an irregular hepatotomy with direct suture and resectional debridement or atriocaval shunting, are thought to be indicated in the emergency setting in specialist units[7,8]. Fast and effective surgical damage control procedures (i.e., temporary gauze packing and mesh wrapping of the fragmented liver with absorbable mesh (mesh hepatorrhaphy) combined with ipsilateral ligation of the bleeding vessel) are safe and effective for treating severe liver injuries, especially in non-specialist centers or in remote, rural settings. Interventional radiological techniques are becoming more widely used to more effectively manage severe liver injuries, particularly in patients who are managed non-operatively or have been stabilized using perihepatic packing[8]. Liver transplantation for trauma is extremely rare; although this type of transplantation has been attempted[9], it is very limited to date.

Although temporary perihepatic gauze packing was not used for decades, packing has been reintroduced because more aggressive attempts at controlling hemorrhaging without temporary packing failed to improve results. Packing is also recommended for inexperienced surgeons to control and stabilize patients before they are transferred to a tertiary center[4,5,7,8]. The patient in this case study suffered from blunt trauma in a traffic accident. Although the surgical details are obscure due to the passing of 39 years, perihepatic gauze packing saved the patient’s life, and she lived a normal life for 39 years. Mesh hepatorrhaphy may control bleeding without many of the adverse effects of packing[4,7,8].

Migrated foreign bodies

Migrated foreign bodies are sharp objects that perforate the alimentary tract and migrate to the liver[10]. Ingested foreign bodies with sharp pointed end include sewing needles, dental plates, fish bones, chicken bones and office supplies. Foreign bodies are commonly ingested by elderly individuals, children, psychiatric patients, prison inmates, alcoholics, certain professionals (e.g., carpenters and dressmakers) and individuals wearing dentures[10-20].

The migration of foreign bodies from the gut into the liver is often a slow process that encourages an inflammatory and fibrotic reaction that results in adhesion[11,12]. Clinical manifestations, such as perforation, bleeding and bowel obstruction, often do not occur with migrated foreign bodies[13]. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract by a foreign body typically occurs at sites at which a physiological narrowing of the stomach[14,15] or duodenum[16,17] is present. Ingestion history is not often considered in the initial diagnosis[13-17]. Migrated foreign bodies in the liver often cause pyogenic liver abscesses or pseudotumors[18].

Patients who present with a liver abscess or a pseudotumor may have a foreign body granuloma, which may be difficult to distinguish from a tumor upon radiological examination. Right upper-quadrant pain and cholangitis[11,12] are often the first symptoms, which may be mild initially but increase over time. An inflammatory mass mimicking a liver abscess or a pseudotumor that looks like hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma may cause systemic symptoms, such as fevers and chills, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting[12,13]. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT can reveal a hepatic abscess with a linear calcified foreign body and gas (which is often hyperechoic in ultrasonography and highly dense in the CT[18,19]) and are very helpful for establishing the correct diagnosis. A CT scan can demonstrate the location of the foreign body clearly and accurately, which may assist the clinician in selecting the appropriate treatment plan.

Conservative management has been described for asymptomatic patients with a stable, uncomplicated migrated foreign body[11,12,16]; however, in an emergency, a hepatic migrated foreign body should be extracted through laparotomy or laparoscopy[17,18] to avoid complications, such as hemorrhaging or the formation of an abscess or a fistula. Other strategies for removing the foreign body include endoscopy[19] and percutaneous abscess drainage under ultrasonographic guidance[20].

Medical foreign bodies

Medical foreign bodies in the liver include surgical objects, such as surgical gauze (or gossypiboma/textiloma)[21-23], surgical clips[24,25], medical sutures[23,26], shrapnel splinters[27] and T-tubes[28], which are retained in the liver parenchyma or biliary tracts after surgical operations. These bodies can be grouped into two main categories: bodies in the biliary tract and bodies in the liver parenchyma.

Gossypibomas account for most of the malpractice claims for retained foreign bodies. They are most frequently observed in obese patients or patients in unstable conditions; during emergency surgeries, long operations or surgical procedures that include unexpected changes; and after laparoscopic interventions[29,30]. Gossypibomas in the liver parenchyma or the biliary tracts commonly follow cholecystectomy or liver surgery[28-30]. In our case, the patient underwent an emergent hepatorrhaphy that included perihepatic packing with surgical gauze. Typically, surgical gauze should be extracted when hemorrhaging stops; however, the gauze in the liver of our patient was not extracted and caused gossypiboma.

The symptoms of gossypiboma are usually non-specific and may appear years after surgery. Pain, irritation, a palpable mass, anorexia, fever and weight loss are the common signs and symptoms of gossypibomas in the liver parenchyma; however, some patients were asymptomatic or presented with foreign body granulomas mimicking liver metastasis[1]. The signs and symptoms of foreign bodies in the biliary tracts include jaundice and elevated liver enzymes[30]. The patient in this case complained of slight intermittent chest pain and dyspnea upon exertion, poor appetite and weight loss. The mass was palpable, but jaundice was absent.

Eguchi et al[27] reported a case of a shrapnel splinter in the common bile duct (CBD) that had migrated from the right thoracic cavity 36 years after the initial injury. It was serially documented that the shrapnel had migrated toward the diaphragm and then burrowed into the liver, settling in the CBD and causing obstructive jaundice. This timeframe represents the longest time reported in the literature that a foreign body remained in liver. In our case, the retained gauze was extracted 39 years later. To our knowledge, this is the longest time that a medical foreign body has been retained in the abdomen.

The most common detection methods are CT, radiography and ultrasound[22]. The most impressive imaging findings of gossypiboma are curved or banded radio-opaque lines on a plain radiograph. The ultrasound usually shows a well-defined mass with a wavy internal echogenic focus, a hypoechoic rim and a strong posterior shadow[31]. On a CT, a gossypiboma may manifest as a cystic lesion with an internal spongiform appearance with hyperdense capsules, concentric layering and mottled shadows as bubbles or mottled mural calcifications[32]. Magnetic resonance imaging pictures of gossypiboma in the abdomen and the pelvis reflect a well-defined mass with a peripheral wall of a low signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted imaging, and T1-weighted imaging shows whorled stripes in the central portion and peripheral wall enhancement after intravenous gadolinium administration[33]. In our case, the patient’s hepatic ultrasound showed a round mass with fluid echogenicity in the right liver lobe. The plain (Figure 1A), contrast-enhanced (Figure 1B) and reconstructive (Figure 1C) abdominal CT scans showed a cystic mass in the liver with filiform calcification inside, mottled mural calcifications and a small amount of pleural effusion.

Early diagnosis may be difficult, and the removal of a medical foreign body is crucial for preventing serious complications and medicolegal issues. The strategies for removing a medical foreign body include laparoscopy and laparotomy for foreign bodies in the liver parenchyma or in the CBD. If endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram is futile, percutaneous abscess drainage under ultrasonographic guidance will be useful[23]. The patient described in this case study underwent an exploratory laparotomy. The surgical gauze in her right liver was extracted, and double-lumen drainage was performed.

The retention of medical foreign bodies can be prevented with simple precautions, such as keeping a thorough pack count. The use of radiologically tagged materials is recommended, and radiofrequency chip identification with a barcode scanner will hopefully decrease the incidence of retained medical foreign bodies[34,35].

In conclusion, retained foreign bodies in the liver can be classified into three categories: penetrating, medical and migrated foreign bodies. Any patient who presents with a hepatic mass and has a history of liver injury, surgery or an occult infection of unknown cause should arouse suspicion of a retained foreign body.