Published online May 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3169

Revised: March 27, 2013

Accepted: April 9, 2013

Published online: May 28, 2013

Processing time: 127 Days and 15.9 Hours

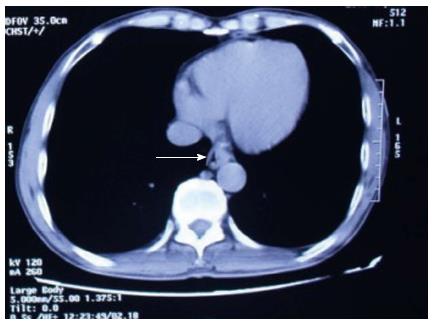

The number of patients developing esophageal cancer after gastrectomy has increased. However, gastric remnant is very rarely used for reconstruction in esophageal cancer surgery because of the risk of anastomotic leakage resulting from insufficient blood flow. We present a case of esophageal cancer using gastric remnant for esophageal substitution after distal gastrectomy in a 57-year-old man who presented with a 1-month history of mild dysphagia and a background history of alcohol abuse. Gastroscopy showed a 1.2 cm × 1.0 cm bulge tumor of the lower third esophagus with the upper margin located 39 cm from the dental arcade. Computed tomography of the chest showed lower third esophageal wall thickening. The patient underwent en bloc radical esophagectomy with a two-field lymph node dissection of the upper abdomen and mediastinum via a left-sided posterolateral thoracotomy through the seventh intercostal space. The upper end of the esophagus was resected 5 cm above the tumor. The gastric remnant was used for reconstruction of the esophago-gastrostomy and placed in the left thoracic cavity. The patient started a liquid diet on postoperative day 8 and was discharged on the 10th postoperative day without complications. In this report, we demonstrate that the gastric remnant may be used for reconstruction in patients with esophageal cancer as a substitute organ after distal gastrectomy.

Core tip: Gastric remnant is very rarely used for reconstruction in esophageal cancer surgery because of the risk of anastomotic leakage resulting from insufficient blood flow. We present a case of esophageal cancer using gastric remnant for esophageal substitution after distal gastrectomy in a 57-year-old man, who was successfully treated with esophagectomy and remnant stomach reconstruction without micro-vascular anastomosis. The gastric remnant may be used for reconstruction in patients with esophageal cancer as a substitute organ after distal gastrectomy, with rapid recovery of bowel function and shorter hospital stay.

- Citation: Xie SP, Fan GH, Kang GJ, Geng Q, Huang J, Cheng BC. Esophageal reconstruction with remnant stomach: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(20): 3169-3172

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i20/3169.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3169

The number of patients developing esophageal cancer after gastrectomy has increased. Reconstruction is a challenge in esophageal cancer surgery when a previous subtotal gastric resection has been performed. In general, there has been a tendency to select the colon or jejunum for substitution of the gastric tube, in order to avoid anastomotic leakage resulting from insufficient blood flow, which requires complicated operative procedures and leads to higher operative morbidity and mortality[1,2]. Herein, we report a patient with esophageal cancer and previous distal gastrectomy, who was successfully treated with esophagectomy and remnant stomach reconstruction without micro-vascular anastomosis.

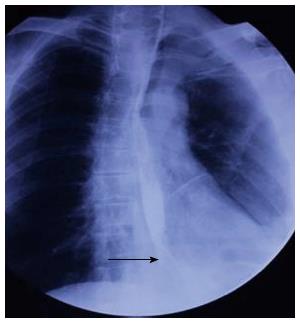

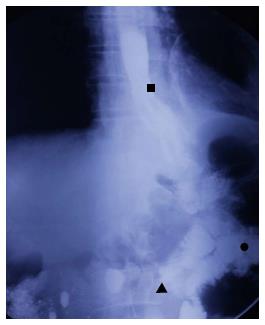

A 57-year-old man had undergone distal gastrectomy with lymph node dissection 7 years previously for gastric cancer with a Billroth II anastomosis, pathologically diagnosed as highly differentiated adenocarcinoma, pT2N0M0; stage Ib, according to the 7th edition of the UICC-TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors[3]. He was admitted to our hospital with a history of mild dysphagia with solids only for one month. His medical history was notable for alcohol abuse. Physical examination of the chest and abdomen revealed no abnormal findings. Barium esophagography revealed an approximately 1 cm arc filling defect in 1/3 of the lower esophagus with local mucosal damage and wall stiffness. The size of the gastric remnant was measured before surgery with contrast barium esophagography X-ray and was found to be 10 cm in length at the lesser curvature (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the chest showed thickening of the lower third of the esophageal wall (Figure 2). Gastroscopy confirmed a 1.2 cm × 1.0 cm bulge tumor in the lower third of the esophagus with the upper margin located 39 cm from the dental arcade (Figure 3). The lesion did not stain with Lugol’s solution. Pathological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed squamous cell carcinoma. Exclusion of cerebral, abdominal, skeletal, lymph node and other distal metastases (M0) was accomplished using [18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography, and distant metastases to other organs were not found.

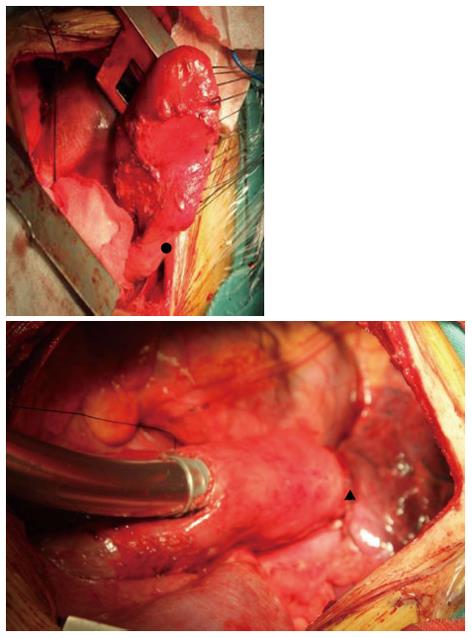

Prior to surgery, the complete colon was examined by endoscopy, and the bowel was prepared by mechanical cleansing. The patient underwent en bloc radical esophagectomy via a left-sided posterolateral thoracotomy through the 7th intercostal space, with a two-field lymph node dissection in the upper abdomen and mediastinum. The upper end of the esophagus was resected 5 cm above the tumor, and the left gastric artery and short gastric artery were then divided. The remnant stomach was freed up to the gastro-esophageal junction, and appeared rosy with adequate bloody supply probably due to the efferent jejunal flap with its wide gastrojejunal anastomosis (Figure 4). We decided to preserve the remnant stomach for reconstruction. The jejunum was freed from surrounding tissues. A gastric tube was extended far enough to reach the proximal esophagus. An esophagogastric anastomosis was performed mechanically under the level of the left inferior pulmonary vein using a circular stapler by an anterior gastrotomy to the high point of the fundus of the gastric remnant. The gastric remnant was placed in the left thoracic cavity. A micro-vascular anastomosis was not performed. Enteral nutrition therapy was via a jejunal stoma. The operative time was 266 min and the estimated blood loss was 435 mL.

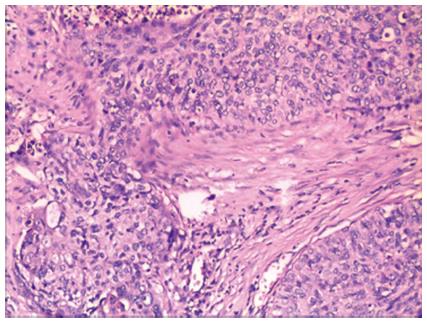

Histologically, the tumor was diagnosed as a highly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with tumor-free margins (Figure 5), and metastases in the abdomen and mediastinum lymph node were not found. The pathological stage was pT2N0M0; stage Ib, according to the 7th edition of the UICC-TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors[3].

The postoperative course was uneventful, with no complications resulting from insufficient blood supply. The integrity of the anastomosis of the esophago-gastrostomy was confirmed by water soluble contrast radiography on postoperative day 7, with no signs of leakage or stricture (Figure 6). The patient started a liquid diet the following day and was discharged on the 10th postoperative day without complications. On follow-up at 6 mo after surgery, the patient was alive with no evidence of recurrence. He had improved food intake; mainly managing a solid diet with an average intake per meal of approximately 450 mL. Barium esophagography confirmed the absence of stricture, with efficient emptying of the remnant stomach.

It was first reported in 1970 that a high incidence of gastrectomy (8.7%) was found in patients with esophageal cancer. Although surgical resection is the standard treatment for esophageal cancer after subtotal gastrectomy, the optimal management of this disease, including the surgical approach and the conduit for reconstruction, remains controversial. For patients with esophageal cancer and a history of gastrectomy, the esophagus is frequently reconstructed using colon interposition with a vascular pedicle[4]. The disadvantages of colon interposition include a long operative time for colon mobilization, highly invasive procedures and additional anastomosis, which increase the incidence of postoperative complications[5]. Increased blood loss was observed when resolving adhesions in the upper abdominal cavity caused by gastrectomy. When using the remnant stomach, the procedure is easier, and the aims are to minimize surgical insults and to maximize the patient’s quality of life. A reduction in the number of surgical maneuvers below the transverse colon and fewer bowel anastomoses represent real advantages[6]. In addition, use of the gastric remnant for reconstruction may offer substantial advantages to the elderly population in terms of fewer cardiac and pulmonary complications, rapid recovery of bowel function, shorter hospital stay, and a faster return to physical activities.

A remnant stomach can last for more than five years before the diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Establishment of the collateral circulation is important for healing of the anastomotic stoma. The blood supply of the remnant stomach may be maintained by the reconstituted micro-vascular supply from the widely anastomosed jejunal loop or vascular adaptation of the stomach and anastomotic site[6], which may enhance perfusion of the gastric tube at the time of anastomosis and thus decrease anastomotic complications after esophagogastrectomy. Reavis demonstrated that gastrointestinal anastomoses were associated with both vasodilation and angiogenesis and resulted in increased blood flow to the gastric fundus prior to esophagogastric anastomosis in animals, which translated into a decrease in anastomotic dehiscence[7]. In our case, wide gastrojejunal anastomosis was seen in this operation. During surgery, 30 min after the left, right and short gastric vessels were cut, the remnant stomach was still rosy (Figure 5). We think that this wide anastomosis maintained the blood supply in the remnant stomach by reconstituting the intramural network. No complications occurred during the postoperative period, and barium esophagography on the 7th postoperative day showed that barium passed smoothly through the anastomotic stoma, without leakage. Preoperative bowel preparation should be conducted in such patients. If a poor blood supply in the remnant stomach is seen during surgery, then colon interposition should be used to replace esophageal surgery.

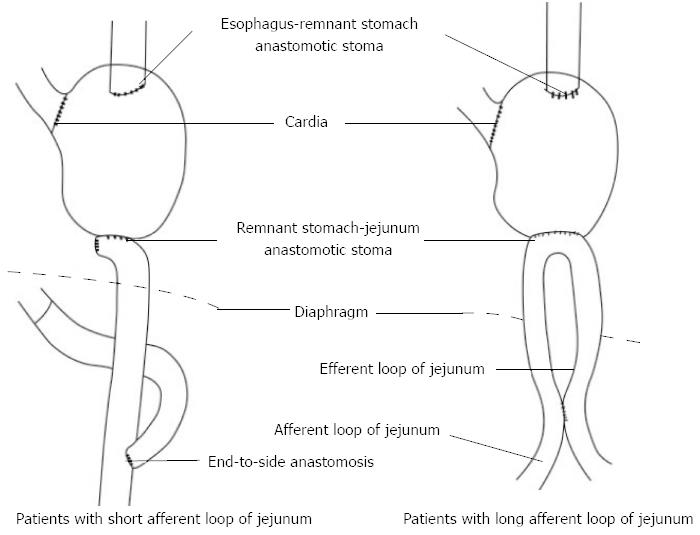

If the remnant stomach can not be lifted to the thorax to perform tension-free anastomosis with the esophagus during esophagectomy, the length of the afferent loop of the jejunum should be observed, if the afferent loop is short, it should be cut at the anastomotic stoma and an end-to-side anastomosis with the efferent loop of the distal jejunum should be performed; if the afferent loop is long, a side-to-side anastomosis should be performed 10-15 cm from the afferent and efferent loops, thus increasing the lifting height of the remnant stomach and jejunal loop (Figure 7).

We report a patient with esophageal cancer and previous distal gastrectomy who was successfully treated with esophagectomy and remnant stomach reconstruction without micro-vascular anastomosis. It is important to select an appropriate operative method for patients with esophageal cancer after distal gastrectomy, and its location and stage must be determined. The remainder of the stomach can be used as an esophageal substitute depending on the curability of the esophageal cancer and the blood supply, which allows rapid recovery of bowel function and shorter hospital stay.

P- Reviewers Melloni G, Tanaka S, Xu XC S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Kolh P, Honore P, Degauque C, Gielen J, Gerard P, Jacquet N. Early stage results after oesophageal resection for malignancy - colon interposition vs. gastric pull-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davis PA, Law S, Wong J. Colonic interposition after esophagectomy for cancer. Arch Surg. 2003;138:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1721-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mine S, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Ueno M, Ehara K, Haruta S. Colon interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1647-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wada H, Doki Y, Nishioka K, Ishikawa O, Kabuto T, Yano M, Monden M, Imaoka S. Clinical outcome of esophageal cancer patients with history of gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dionigi G, Dionigi R, Rovera F, Boni L, Carcano G. Reconstruction after esophagectomy in patients with [partial] gastric resection. Case report and review of the literature of the use of remnant stomach. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Reavis KM, Chang EY, Hunter JG, Jobe BA. Utilization of the delay phenomenon improves blood flow and reduces collagen deposition in esophagogastric anastomoses. Ann Surg. 2005;241:736-745; discussion 745-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |