Published online May 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3018

Revised: March 5, 2013

Accepted: April 10, 2013

Published online: May 28, 2013

Processing time: 138 Days and 10.5 Hours

AIM: To analyze trends in incidence and mortality of acute pancreatitis (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) in the Netherlands and for international standard populations.

METHODS: A nationwide cohort is identified through record linkage of hospital data for AP and CP, accumulated from three nationwide Dutch registries: the hospital discharge register, the population register, and the death certificate register. Sex- and age-group specific incidence rates of AP and CP are defined for the period 2000-2005 and mortality rates of AP and CP for the period 1995-2005. Additionally, incidence and mortality rates over time are reported for Dutch and international (European and World Health Organization) standard populations.

RESULTS: Incidence of AP per 100000 persons per year increased between 2000 and 2005 from 13.2 (95%CI: 12.6-13.8) to 14.7 (95%CI: 14.1-15.3). Incidence of AP for males increased from 13.8 (95%CI: 12.9-14.7) to 15.2 (95%CI: 14.3-16.1), for females from 12.7 (95%CI: 11.9-13.5) to 14.2 (95%CI: 13.4-15.1). Irregular patterns over time emerged for CP. Overall mean incidence per 100000 persons per year was 1.77, for males 2.16, and for females 1.4. Mortality for AP fluctuated during 1995-2005 between 6.9 and 11.7 per million persons per year and was almost similar for males and females. Concerning CP, mortality for males fluctuated between 1.1 (95%CI: 0.6-2.3) and 4.0 (95%CI: 2.8-5.8), for females between 0.7 (95%CI: 0.3-1.6) and 2.0 (95%CI: 1.2-3.2). Incidence and mortality of AP and CP increased markedly with age. Standardized rates were lowest for World Health Organization standard population.

CONCLUSION: Incidence of AP steadily increased while incidence of CP fluctuated. Mortality for both AP and CP remained fairly stable. Patient burden and health care costs probably will increase because of an ageing Dutch population.

Core tip: Large scale epidemiological studies reporting time trends of incidence and mortality of chronic pancreatitis (CP) are strikingly scarce compared to the also limited epidemiological studies on acute pancreatitis (AP). Reported are the Dutch incidence rates of AP and CP for the period 2000-2005, and mortality rates of AP and CP for the period 1995-2005. The incidence rates of AP steadily increased while the incidence of CP fluctuated. Population mortality for both AP and CP remained fairly stable. Both incidence and mortality rates increased markedly by age. So, especially in ageing populations, it is to be expected that patient burden and health care costs will increase.

- Citation: Spanier BM, Bruno MJ, Dijkgraaf MG. Incidence and mortality of acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands: A nationwide record-linked cohort study for the years 1995-2005. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(20): 3018-3026

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i20/3018.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i20.3018

Over the last decades, the incidence and number of hospital admissions of both acute pancreatitis (AP)[1-10] and chronic pancreatitis (CP) have consistently increased in the Western countries[11-14]. Increasing alcohol intake, more gallstone-related pancreatitis, increased pancreatic enzyme testing and improvements of diagnostic tests and interventional techniques have all been suggested as possible explanations[4,5,6,8,15-17].

The disease spectrum of AP ranges from mild and self-limiting (approximately 85%) to a life-threatening illness resulting in significant morbidity and mortality[18-21]. At onset, AP regularly results in hospitalization[22,23]. Generally, in the Western countries the case fatality proportion of AP decreased over time, but the overall population mortality did not change[2,16].

CP is characterized by ongoing or recurrent episodes of abdominal pain accompanied by progressive pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Hospitalization is required in case of an exacerbation to control pain (e.g., opioid medication, endoscopic duct drainage, pancreaticojejunostomy and/or resection) and for the treatment of complications such as pseudocysts[15,16,24,25]. The overall survival for CP patients is reduced compared with the general population. Most notably because of the impact of non-pancreatic effects of excess alcohol consumption and/or smoking, independent of CP itself[15,16].

Epidemiological studies from the Netherlands for AP are scarce and this is even more the case for CP[2,11,22]. Eland et al[2] reported the latest incidence rates and mortality of AP from 1985 to 1995, both based on hospital discharge data. Our group reported about the trend in hospital admissions in the Netherlands for AP and CP[11]. For both groups, the hospital admissions have increased substantially from 1992 to 2004.

In this study we report the incidence rates of AP and CP for the period 2000-2005 and mortality rates of AP and CP for the period 1995-2005 following linkage of three distinct nation-wide Dutch registries. Additionally, data on incidence and mortality rates over time are reported for Dutch and international standard populations.

Cases of AP and CP were identified by linkage of three distinct nation-wide Dutch registries: the hospital discharge register [HDR: formerly also known as the National Information System on Hospital Care (NISHC)], the population register (PR), and the death certificate register (DCR). The HDR contains discharge data from academic and general hospitals in the Netherlands (http://www.dutchhospitaldata.nl/). Since 1992 almost all (> 97%) Dutch hospitals are linked to the HDR with 99% coverage of all hospital admissions. For each hospital discharge the dates of admission and discharge, type of admission, and diagnoses at discharge (primary and secondary) are recorded along with anonymous patient characteristics like: sex, date of birth, postal code of the living address, and country of origin. Hospital discharge diagnoses in the HDR are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM). We retrospectively retrieved all hospital admissions (> 1 d of hospital stay) for the period 1 January 1995-31 December 2005 from the HDR with acute (code 577.0) or chronic (code 577.1) pancreatitis as the primary discharge diagnoses.

A single patient with multiple admissions will have several records in the HDR. Because of its anonymous nature however, only partially identifiable information is provided at the record level. For the accurate count of pancreatitis cases, it is necessary to identify different admissions, potentially in different hospitals, by the same patient. To identify these unique cases in the HDR the records were linked to the PR which is maintained by Statistics Netherlands of the Dutch Ministry of Economy Affairs. The PR contains continuously updated demographic data on all citizens residing in the Netherlands like name, date of birth, sex, nationality, living address, dates of immigration and/or emigration, and date of death.

HDR records can be linked to the PR by a combination of three identifiers: sex, date of birth, and (the numeric part of) the postal code at the time of admission. Linkage fails if several citizens are of the same sex, are born on the same date, and live in the same postal code area at the time at least one of them is admitted (“administrative siblings”). Also, linkage fails if any key data are lacking in the HDR or in the PR.

Statistics Netherlands enables the unique linkage of about 86% of all yearly hospital admissions to the PR, suggesting that counts at the person level should be multiplied by 100/86 to derive national estimates. However, the probability of unique linkage is not equal across subgroups in the general population and over time. For instance, persons in high-density population areas, persons born in countries with inaccurate birth dates, and moving persons have a lower probability of unique linkage. To compensate for linkage failure, stratum-specific multipliers were calculated for sex, 5-yearly age cohorts, and country of origin (available from the corresponding author upon request). While doing so, we took into account that our aim was to estimate the incidence rather than the prevalence of AP and CP.

We defined an incident case during any specific year as a person with an admission for AP or CP during that year which is not preceded by another admission of the same person with the same discharge diagnosis during at least five years prior to the specified year. To identify incident cases, it is mandatory that all admissions during the observation period have been identified for each person. Hence, a person known in the PR should be always uniquely identifiable during the observation period 1995-2005 based on the linkage keys sex, age, and the postal code.

Sex- and age- specific incidence rates for the years 2000-2005 were defined as the yearly number of new pancreatitis cases per 100000 members of the Dutch reference population alive during the year, excluding immigrated or emigrated citizens and after adjustment for stratum-specific linkage failure between the HDR and the PR[26]. The yearly incidence rates were standardized with reference to the age and sex distribution of the Dutch reference population in 2000 to identify the possible impact of a Dutch ageing population on the observed trends in incidence rates over time. Standardizations were also performed with reference to the age distribution (assuming evenly distributed male and females) of the European and World Health Organization (WHO) standard populations to enable direct comparisons among trends in incidence and mortality rates across countries that differ by age (and sex) distributions of their respective populations[27].

Deaths associated with AP and CP were identified by linkage of the PR and the DCR which is also maintained by Statistics Netherlands.

General practitioners and hospitals are obliged to complete a death certificate for each deceased person, and notify the primary and up to three secondary causes of death. Causes of death are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases coding system with acute and chronic pancreatic related death coded as 577.0 and 577.1 respectively for the year 1995 (ICD-9CM) or K850 and K860/K861 respectively for the years 1996 and later (ICD-10CM). The register is nearly complete (99.7%) with regard to persons deceased in the Netherlands, meaning that deaths after emigration are lacking. For their completeness and reliability, only the primary causes of death were analyzed. The mortality rate was expressed per 1000000 general population members excluding the ones that emigrated any time between 1995 and 2005. Again, yearly mortality rates were recalculated with reference to the age and sex distribution of the Dutch reference population in 2000 as well as with reference to the age distribution of the European and WHO standard populations.

We assumed the AP and CP incidence and mortality rates to follow Poisson distributions when calculating 95%CI. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences versions 14.0 and 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) were used for statistical analysis.

In 1995-2005, 18819221 citizens were known in the population register with 49.75% being male. Slightly under 10.4 percent immigrated or emigrated, leaving 16866819 patients in the Dutch reference population for the incidence estimates, 12163581 of whom were always uniquely identifiable during 1995-2005. Hence, the average multiplier for the incidence estimates amounted to 1.387.

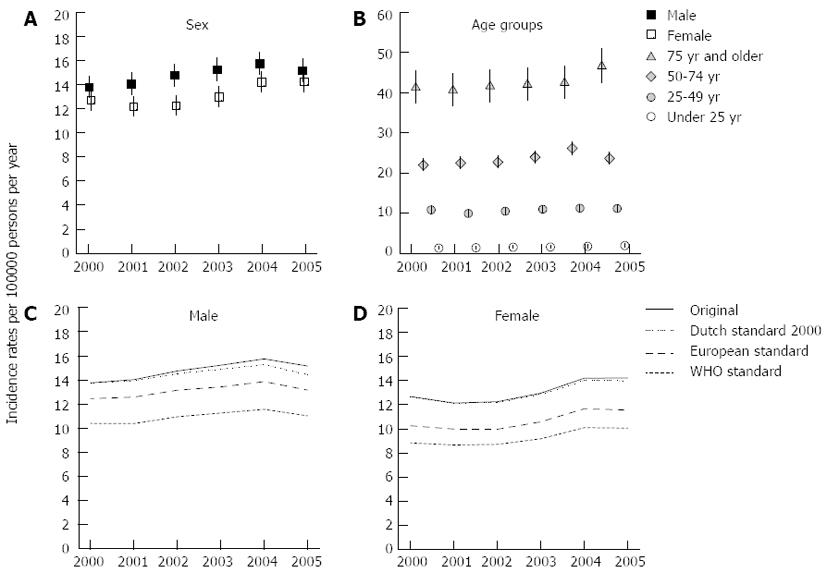

The overall incidence rate of AP increased during the 2000-2005 period from 13.2 (95%CI: 12.6-13.8) in 2000 to 14.7 (95%CI: 14.1-15.3) in 2005. The incidence rate for males rose from 13.8 (95%CI: 12.9-14.7) to 15.2 (95%CI: 14.3-16.1), for females from 12.7 (95%CI: 11.9-13.5) to 14.2 (95%CI: 13.4-15.1), reflecting yearly increases of 1.6% and 1.9% respectively (Figure 1A).

Incidence rates ranged from below 1 in the younger age groups (< age 15 years) to as high as 50.7 in 2005 for the patients of 85 years and above. Figure 1B shows the incidence rates for four major age groups (< 25, 25-49, 50-74 and > 74 years). The incidence rate in the 50-74 age group was highest in 2004 (26.1; 95%CI: 24.6-27.7); in the eldest age group the incidence rate was increased in 2005 (46.5; 95%CI: 42.5-50.9) compared to the preceding years.

The mean yearly incidence rates of AP by 5-yearly age groups and by sex peaked at the ages of 80-84 for both, males (55.4; 95%CI: 42.8-71.6) and females (41.9; 95%CI: 33.8-52.0). The mean yearly incidence rate was higher for females (7.1; 95%CI: 4.7-10.7) than males (3.4; 95%CI: 1.9-6.0) for persons in their early twenties. However, between the ages of 44 and 84, the opposite was observed with 30%-63% higher mean yearly incidence rates for males than for females.

Figure 1C and D (males and females) show the original as well as the Dutch 2000, the European and the WHO standardized incidence rates of AP. Both figures show lowest incidence rates for the WHO standard population (range males: 10.4-11.6; range females: 8.6-10.1), followed by the European standard population (range males: 12.5-13.9; range females: 10.0-11.7), and the Dutch standard population (range males: 13.8-15.3; range females: 12.1-14.0). The figures show that the discrepancy between the original incidence rate and the standardized rates increases over time for males, indicating a small effect of an ageing Dutch population.

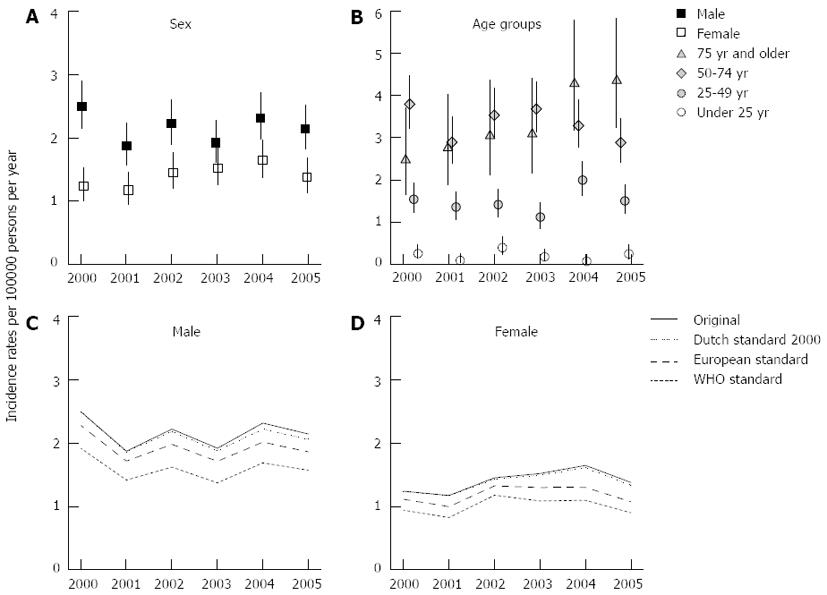

The overall incidence rate of CP during the 2000-2005 period averaged 1.77, fluctuating between 1.52 (95%CI: 1.32-1.74) in 2001 and 1.98 (95%CI: 1.76-2.22) in 2004. Figure 2A shows the incidence rates of male and female CP cases. The incidence rates for males averaged 2.16, 50% higher than the incidence rates for females (mean of 1.4). The incidence rates for males fluctuated over time with lower rates in the years 2001 and 2003 (both 1.9; 95%CI: 1.6-2.3) compared with the year 2000 (2.5; 95%CI: 2.1-2.9). Among females, the incidence rates during the years 2003 (1.5; 95%CI: 1.3-1.8) and 2004 (1.6; 95%CI: 1.4-2.0) were higher than during the year 2001 (1.2; 95%CI: 0.9-1.5).

Incidence rates ranged from below 0.5 in the younger age groups (< age 20 years) to as high as 5.2 (95%CI: 3.5-7.8) in 2005 for the patients between 75 and 79 years of age. Figure 2B shows the incidence rates for four major age groups (< 25, 25-49, 50-74 and > 74 years). While the incidence rate fluctuated in the 50-74 years age group between 3.8 (95%CI: 3.2-4.5) in 2000 and 2.9 (95%CI: 2.4-3.5) in 2001 and 2005, the incidence rate in the age group of 75 and older increased steadily by 75%, from 2.5 (95%CI: 1.7-3.7) in 2000 to 4.4 (95%CI: 3.2-5.8) in 2005.

The mean yearly incidence rates of CP for males between 65 and 74 years (65-69 years: 6.2, 95%CI: 3.9-9.8; 70-74 years: 5.1, 95%CI: 3.0-8.9) more than doubled the rates for females (65-69 years: 2.3, 95%CI: 1.2-4.7; 70-74 years: 2.4, 95%CI: 1.2-5.0).

Figure 2C and D (males and females) show the original as well as the Dutch 2000, the European and the WHO standardized incidence rates of CP. The incidence rates for the WHO standard population ranged from 1.4 to 1.9 for males and from 0.8 to 1.2 for females. For the European standard population, the ranges were 1.7-2.3 and 1.0-1.3 for males and females respectively. The ranges for the Dutch standard population in 2000 (range males: 1.9-2.5; range females: 1.2-1.6) were nearly identical to the non-standardized data.

Between 1995 and 2005, 1524492 persons died in the Netherlands. In 2264 cases AP was notified as a cause of death. Of these, 65.6% or 1484 cases (0.97 pro mille of all deceased persons) died with AP as the primary cause of death, including 764 males and 720 females.

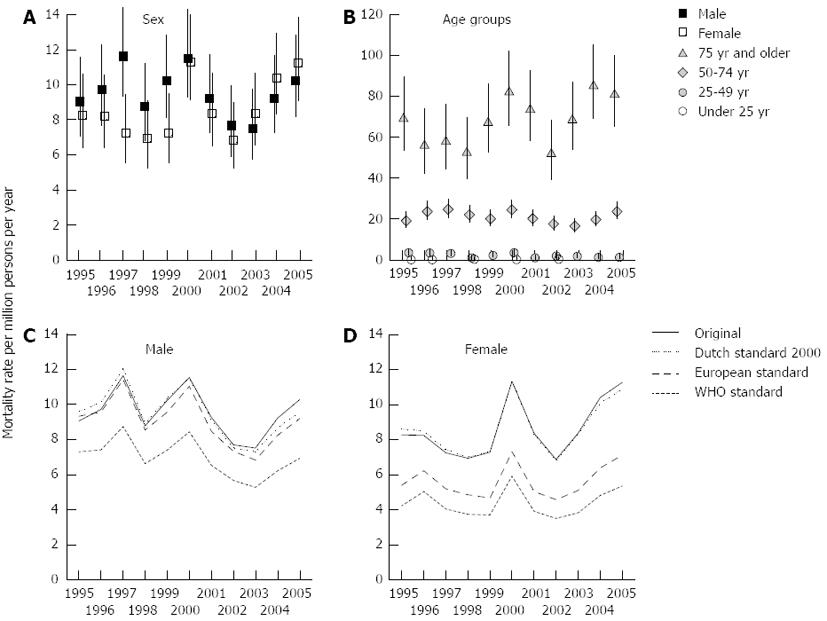

Figure 3A shows the male and female mortality rates of AP for 1995-2005. The mortality rates fluctuated between 6.9 and 11.7 were similar for males and females except for the years 1997 and 1999 when more males than females died (1997: 11.7; 95%CI: 9.4-14.5 vs 7.26; 95%CI: 5.56-9.48); 1999: 10.3; 95%CI: 8.2-12.9 vs 7.3; 95%CI 5.61-9.51). Figure 3B shows the mortality rates for four major age groups (< 25, 25-49, 50-74 and > 74 years). The mortality rate for patients younger than 50 years of age stayed below 3.6 (95%CI: 2.3-5.6) and for the 50-74 years age group below 18.6 (95%CI: 14.8-23.5), whereas the mortality rate more than tripled up to 85.3 (95%CI: 69.1-105.4) for the oldest age group.

Figure 3C and D (males and females) show the original as well as the Dutch 2000, the European, and the WHO standardized mortality rates of acute pancreatitis. An ageing effect for males is present with in 1995 a 6.1% higher and in 2005 a 7.1% lower Dutch standardized rate compared to the original rate. On average, the mortality rates for the European and Dutch standard populations are 31.6%, respectively 36.8% higher than the WHO standard. Although the overall pattern is irregular, a gradual decline over time in mortality rates for males can be noted.

Among the females a smaller ageing effects emerges with in 1995 a 4% higher and in 2005 a 3.4% lower Dutch standardized rate compared to the non-standardized rate. On average, the mortality rates for the European and WHO standard populations are 52.7%, respectively 96.8% below the Dutch standard.

Between 1995 and 2005 745 patients died in the Netherlands with CP notified as a cause of death. Of these, 43.9% or 327 cases (0.21 pro mille of all deceased Dutch patients in the same period) died with CP as the primary cause of death, including 223 males and 104 females.

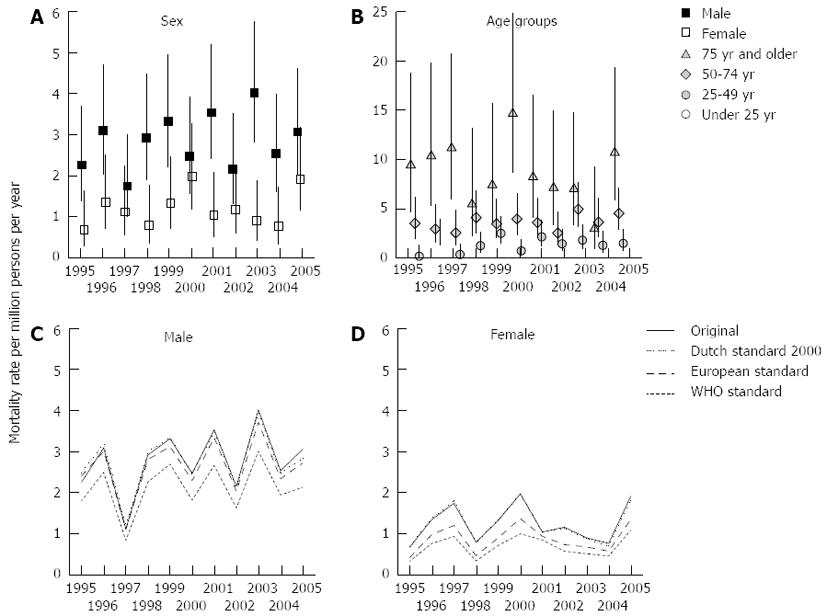

Figure 4A shows the male and female mortality rates of CP for 1995-2005. The mortality rates for males fluctuated between 1.1 (95%CI: 0.6-2.3) in 1997 and 4.0 (95%CI: 2.8-5.8) in 2003, for females between 0.7 (95%CI: 0.3-1.6) in 1995 and 2.0 (95%CI: 1.2-3.2) in 2000. Except for 1997, 2000, 2002 and 2005 the male mortality rate exceeded the female mortality rate.

Figure 4B shows the mortality rates for four major age groups (< 25, 25-49, 50-74 and > 74 years). The mortality rate for patients younger than 50 years of age stayed below 2.3 (95%CI: 1.3-4.0) and for the 50-74 age group below 4.5 (95%CI: 2.9-7.1), whereas for the oldest age group the mortality rate went up to as high as 14.7 (95%CI: 8.7-24.9).

Figure 4C and D (males and females) show the original as well as the Dutch 2000, the European, and the WHO standardized mortality rates of CP for 1995-2005. Again, an ageing effect for males is present with in 1995 a 9.7% higher and in 2005 a 7.1% lower Dutch standardized rate compared to the original rate. On average, the European and WHO standardized rates are 5.9% and 32.4% lower than the Dutch rate. No clear ageing effect is observed for females. On average, the European and WHO standardized rates are 42% and 83.5% lower than the Dutch rate.

We performed a nationwide record-linked study to analyze the time trends of the incidence and mortality rates of AP and of CP in the Netherlands. We show that between 2000-2005 the incidence of AP per 100000 persons per year increased over time for both, males (from 13.8 to 15.2) and females (from 12.7 to 14.2). Relatively stable patterns over time emerged for the incidence rate of AP per 100000 persons per year by different age groups. The steady increase of the incidence of AP over time corresponds to the results of a former retrospective study performed in the Netherlands between 1985-1995[2]. However, the similar growth pattern in our study was observed at a lower level. Eland et al[2] observed incidence rates for the year 1995 of 17.0 males and 14.8 females per 100000 person-years. If we take for granted that no decrease in incidence rates took place during the unobserved years 1996-1999, then several decisions concerning study design may have contributed to the difference in incidence rate level. Eland et al[2] retrieved primary as well as secondary discharge diagnoses from the HDR, whereas we only included AP as a primary discharge diagnosis in order to reduce the risk of misclassification of cases. Further, we excluded single-day admissions for AP. This seems reasonable, because patients with a first attack of AP usually get admitted for several days[2,9]. Moreover, by identifying unique cases following the linkage of two nationwide registries, double counting of cases is a circumvented issue in our study. Considering these reasons for differences in level despite a similar growth pattern, the former reported incidence rates in the Netherlands may be somewhat overestimated.

Other recent population-based studies in Western countries too report increasing incidence rates of AP[3,4,6,7,10,28-31]. The studies - although somewhat heterogeneous by design - indicate that the reported incidence rates of AP in the Netherlands are low and even far lower compared to reported rates from several Scandinavian countries and the United States[16]. The observed differences in incidence rates between these geographical locations are not clearly understood and presumably reflects differences in risk factor prevalence. It has been suggested that the increase of the incidence of AP in the Western countries could be explained by an increase in alcohol intake[16]. According to the registry data of Statistics Netherlands the general self-reported alcohol consumption slightly decreased in the period 2000-2005 (http://www.cbs.nl). Therefore, the incidence increase of acute pancreatitis seems not to be explained by a change in alcohol consumption, at least not in the Netherlands. We observed that the incidence rates of AP increased considerably with age. This is in accordance with observations elsewhere[2-4,7,29].

The incidence rates of CP in the Netherlands have now been reported for the first time. In contrast to AP, irregular patterns over time emerged for the incidence rates of CP per 100000 persons per year for males (mean: 2.16) and females (mean: 1.4). The incidence rate increased with age, with a top in 2005 at 4.4 in the age group of 75 or older. Recent large scale epidemiological studies reporting the time trends of incidence of CP are strikingly scarce[15,16]. The latest reported incidence rates of CP vary between 5.9 and 7.9 per 100000 persons[11,31,32]. In comparison to those studies, our observed incidence rates of CP are somewhat lower. This may in part be explained by our study limitations (see below). In accordance to other studies, we show that CP is predominantly a disease of males[11-13,15,16,31]. The average incidence rate for males is 50% higher than for females. This is even more pronounced in the older age groups.

The mortality rate for AP per million persons per year fluctuated between 6.9 to 11.7 during the 1995-2005 period. Others too reported fairly stable overall annual population mortality rates[2,10,13]. The mortality rate increased rapidly for patients of 50 years of age and above, which too is in accordance with observations elsewhere[2,4,10,29]. Advanced age may be an independent risk factor for severe AP[33]. Mortality rates were almost similar for males and females.

Concerning CP, the mortality rate per million persons per year for both males and females fluctuated within a stable bandwidth. Tinto et al[13] also reported that between 1979 and 1999 the age-standardized mortality rate broadly remained unchanged in England. Merely, the mortality rate for males exceeded the female rate. The mortality rate for persons of 75 years of age and older increased most promptly. Generally, the survival rate for patients with CP is poor[15,16,34,35]. CP patients tend to die of other causes such as smoking related cancers, cardiovascular disease and alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

Both incidence and mortality rates over time are reported for Dutch and international standard populations. On average, the reported rates are the lowest for the WHO standard population, followed by the European and the Dutch standard populations, which clearly reflects their different age distributions. In addition, an ageing effect was observed during the study period, particularly for male incidence rates. The ageing of the Dutch population will most likely continue for another decade, for which reason an increase in patient burden and a rise in health care costs can be anticipated.

Our study has several potential limitations. We defined an incident case during any specific year as a person with an admission that was not preceded by another admission of the same person with the same discharge diagnosis during at least five years prior to the specified year. So, an admitted, incident case in 2000 had no previous admission during 1995-1999 (five years). Further, an admitted, incident case in 2002 had no previous admission in 1995-2001 (seven years). It would have been a contradiction to allow a person to be classified as an incident case in 2002, if he had already been admitted once before in 1996 for the same reason. This analytical approach however may have led to a downward pressure on the incidence rates in later years (near 2005) compared to the earlier years (near 2000). Hence, growth patterns may be slightly underestimated.

Another limitation is that we did not identify incident CP cases among the persons already identified as incident AP cases. Presumably, this resulted in only a minimal underestimation of the incidence rate of CP. A recent study showed that CP developed in alcoholic AP cases with a cumulative incidence of just 13% in 10 years[36]. Only, in patients with a recurrent alcoholic AP, the incidence of CP at 2 years after initial relapse was 38%. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient data about the etiology of AP and CP in our study population.

Another issue concerns the reliability of the reported incidence rates which depends heavily on the HDR as a reliable source for hospital discharge data concerning AP and CP.

Eland et al[2] performed, as a part of a retrospective study in which incidence rates of AP in the Netherlands were assessed, a restricted validation analysis. They concluded that the overreporting due to miscoding and the underreporting due to non-coding were comparable and that observed incidence rates seem to reflect true rates.

Previously, we retrospectively analyzed the reliability of hospital discharge data of in total 483 admissions for both AP and CP collected in the HDR. We observed a substantial miscoding and non-coding of discharge diagnoses of AP and CP on the level of individual hospital admissions, ultimately leading to a limited underestimation at group level of the total number of AP and CP diagnoses of 15.8% and 6% respectively[37].

Furthermore, there is a potential underestimation of the incidence rates due to non-referral of AP and CP patients. For the present study, we retrieved the AP and CP hospital admissions (> 1 d of hospital stay) from the HDR. Underestimation due to non-referral is probably limited for AP, because in the Netherlands almost all AP patients are admitted to a hospital for more than one day[22]. Whether or not this also holds for CP patients in the Netherlands is unknown. Generally, some CP patients, especially in the early stage of the disease, are only treated in an outpatient clinic setting and treated in a single-day hospital admission. So, by excluding the single-day admissions in our study, the underestimation will be of greater importance for CP compared to the AP. Historical volume data from the forerunner of the HDR (the earlier mentioned NISHC) on the use of hospital resources by CP patients suggest that approximately 6% of all admissions are single-day admissions. Considering that individual CP patients frequently need multiple single-day admissions, once under such treatment, it is likely that at the person count level, the degree of underestimation is even less than 6%.

In conclusion, we observed an increase in the incidence rate of AP and a fluctuating incidence rate of CP between 2000 and 2005 in the Netherlands. On average, the mortality rate for both AP and CP remained fairly stable between 1995-2005. Both incidence and mortality rates increase markedly by age and are lower for international standard populations. Therefore, in light of the continuing ageing of the Dutch population, patient burden and health care costs will most probably increase.

Over the last decades, the incidence and number of hospital admissions of both acute pancreatitis (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP) have consistently increased in the Western countries. AP and CP are associated with significant morbidity and mortality and a substantial use of health care resources.

Large scale epidemiological studies reporting time trends of incidence and mortality of CP are strikingly scarce compared to the also limited epidemiological studies on AP. Mostly, national registries are used in isolation for epidemiological studies on AP and CP. Joint application of these registries by record linkage at the level of the individual patients provides a unique opportunity for improving the accuracy of epidemiological data.

By following linkage of three distinct nationwide Dutch registries, the authors report in a more valid way the incidence and mortality rates of AP and CP (now for the first time) in the Netherlands. Standardizations were performed with reference to age distribution of the European and World Health Organization standard populations to enable direct comparisons among trends in incidence and mortality rates across countries that differ by age and sex distributions of their respective populations.

The incidence rates of AP steadily increased while the incidence of CP fluctuated. Population mortality for both AP and CP remained fairly stable. Both, incidence and mortality rates increased markedly with age. In ageing populations, it is to be expected that patient burden and health care costs will increase.

The disease spectrum of AP ranges from mild and self-limiting to a life-threatening illness. CP is characterized by ongoing or recurrent episodes of abdominal pain accompanied by progressive pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. Main etiological factors are gallstones and alcohol abuse.

This is a descriptive study of the trends in incidence and mortality of AP and CP from three linked nationwide Dutch registries for the years 1995-2005. The databases included the hospital discharge registry, the population registry, and the death certificate registry. The authors discuss the limitations of each database and the methods to link them. Given these limitations, major findings included the observation that the incidence of AP increased in both males and females, but the mortality rates remained stable. The incidence and mortality of AP and CP increased with age, which has implications for future incidence in an aging population.

P- Reviewers Ho SB, Kamisawa T S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Brown A, Young B, Morton J, Behrns K, Shaheen N. Are health related outcomes in acute pancreatitis improving? An analysis of national trends in the U.S. from 1997 to 2003. JOP. 2008;9:408-414. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Eland IA, Sturkenboom MJ, Wilson JH, Stricker BH. Incidence and mortality of acute pancreatitis between 1985 and 1995. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1110-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Floyd A, Pedersen L, Nielsen GL, Thorladcius-Ussing O, Sorensen HT. Secular trends in incidence and 30-day case fatality of acute pancreatitis in North Jutland County, Denmark: a register-based study from 1981-2000. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:1461-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey DJ, White RH. The incidence and case-fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic, and idiopathic pancreatitis in California, 1994-2001. Pancreas. 2006;33:336-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963-98: database study of incidence and mortality. BMJ. 2004;328:1466-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lindkvist B, Appelros S, Manjer J, Borgström A. Trends in incidence of acute pancreatitis in a Swedish population: is there really an increase? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roberts SE, Williams JG, Meddings D, Goldacre MJ. Incidence and case fatality for acute pancreatitis in England: geographical variation, social deprivation, alcohol consumption and aetiology--a record linkage study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:931-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaddique S, Cahill RA, Watson RG, O’Connor J. Trends in the incidence and significance of presentations to the emergency department due to acute pancreatitis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13:209-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singla A, Simons J, Li Y, Csikesz NG, Ng SC, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Admission volume determines outcome for patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1995-2001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yadav D, Lowenfels AB. Trends in the epidemiology of the first attack of acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2006;33:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lévy P, Barthet M, Mollard BR, Amouretti M, Marion-Audibert AM, Dyard F. Estimation of the prevalence and incidence of chronic pancreatitis and its complications. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2006;30:838-844. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Trends and forecasts of hospital admissions for acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:653-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tinto A, Lloyd DA, Kang JY, Majeed A, Ellis C, Williamson RC, Maxwell JD. Acute and chronic pancreatitis--diseases on the rise: a study of hospital admissions in England 1989/90-1999/2000. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2097-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang AL, Vadhavkar S, Singh G, Omary MB. Epidemiology of alcohol-related liver and pancreatic disease in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:649-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jupp J, Fine D, Johnson CD. The epidemiology and socioeconomic impact of chronic pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:219-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Epidemiology, aetiology and outcome of acute and chronic pancreatitis: An update. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:45-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yadav D, Ng B, Saul M, Kennard ED. Relationship of serum pancreatic enzyme testing trends with the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Talukdar R, Vege SS. Recent developments in acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:S3-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wu BU, Conwell DL. Acute pancreatitis part I: approach to early management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:410-416, quiz e56-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wu BU, Conwell DL. Acute pancreatitis part II: approach to follow-up. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Eland IA, Sturkenboom MC, van der Lei J, Wilson JH, Stricker BH. Incidence of acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:124. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 549] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Braganza JM, Lee SH, McCloy RF, McMahon MJ. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet. 2011;377:1184-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Conwell DL, Banks PA. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:586-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Van Sijl M; Ophogen op persoonsniveau van gegevens van de Landelijke Medische Registratie gekoppeld met de GBA [article in Dutch]. Voorburg: Central Commission of Statistics, internal report 0160-05-SOO. . |

| 27. | Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. Geneva: World Health Organization, GPE discussion paper series No. 31 2001; . |

| 28. | Birgisson H, Möller PH, Birgisson S, Thoroddsen A, Asgeirsson KS, Sigurjónsson SV, Magnússon J. Acute pancreatitis: a prospective study of its incidence, aetiology, severity, and mortality in Iceland. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ellis MP, French JJ, Charnley RM. Acute pancreatitis and the influence of socioeconomic deprivation. Br J Surg. 2009;96:74-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gislason H, Horn A, Hoem D, Andrén-Sandberg A, Imsland AK, Søreide O, Viste A. Acute pancreatitis in Bergen, Norway. A study on incidence, etiology and severity. Scand J Surg. 2004;93:29-33. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Lankisch PG, Assmus C, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Epidemiology of pancreatic diseases in Lüneburg County. A study in a defined german population. Pancreatology. 2002;2:469-477. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Díte P, Starý K, Novotný I, Precechtelová M, Dolina J, Lata J, Zboril V. Incidence of chronic pancreatitis in the Czech Republic. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:749-750. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Gardner TB, Vege SS, Chari ST, Pearson RK, Clain JE, Topazian MD, Levy MJ, Petersen BT. The effect of age on hospital outcomes in severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2008;8:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, DiMagno EP, Andrén-Sandberg A, Domellöf L, Di Francesco V. Prognosis of chronic pancreatitis: an international multicenter study. International Pancreatitis Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1467-1471. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Thuluvath PJ, Imperio D, Nair S, Cameron JL. Chronic pancreatitis. Long-term pain relief with or without surgery, cancer risk, and mortality. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lankisch PG, Breuer N, Bruns A, Weber-Dany B, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Natural history of acute pancreatitis: a long-term population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2797-2805; quiz 2806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Spanier BW, Schreuder D, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Source validation of pancreatitis-related hospital discharge diagnoses notified to a national registry in the Netherlands. Pancreatology. 2008;8:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |