Published online Jan 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.307

Revised: October 3, 2012

Accepted: October 30, 2012

Published online: January 14, 2013

Processing time: 166 Days and 4.8 Hours

A 53-year-old male developed cervical esophageal stenosis after esophageal bypass surgery using a right colon conduit. The esophageal bypass surgery was performed to treat multiple esophageal strictures resulting from corrosive ingestion three years prior to presentation. Although the patient underwent several endoscopic stricture dilatations after surgery, he continued to suffer from recurrent esophageal stenosis. We planned cervical patch esophagoplasty with a pedicled skin flap of sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. Postoperative recovery was successful, and the patient could eat a solid meal without difficulty and has been well for 18 mo. SCM flap esophagoplasty is an easier and safer method of managing complicated and recurrent cervical esophageal strictures than other operations.

- Citation: Sa YJ, Kim YD, Kim CK, Park JK, Moon SW. Recurrent cervical esophageal stenosis after colon conduit failure: Use of myocutaneous flap. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(2): 307-310

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i2/307.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.307

A variety of total esophageal reconstruction procedures have been described; however, there is no universally-accepted method[1]. Cervical reconstruction for esophageal stenosis of any etiology is complicated and can be more challenging in cases of recurrent cervical stenosis with previous colon conduit failure. Recently, we successfully treated upper cervical stenosis caused by corrosive strictures using colon conduits. However, these operations have been followed by recurrent stenosis. Many different approaches have been utilized in the treatment of cervical stenosis. These include local fasciocutaneous flaps, pedicled myocutaneous flaps, pedicled visceral flaps, free flaps, and free fasciocutaneous flaps[2]. We present a successful patch-plasty with myocutaneous flap of sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle for treatment of recurrent cervical esophageal stenosis.

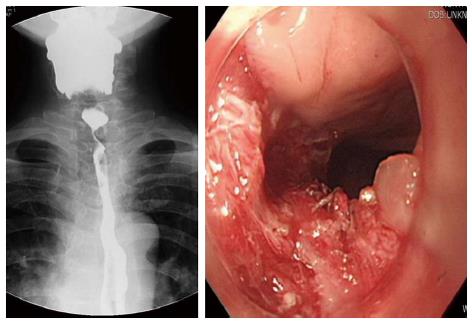

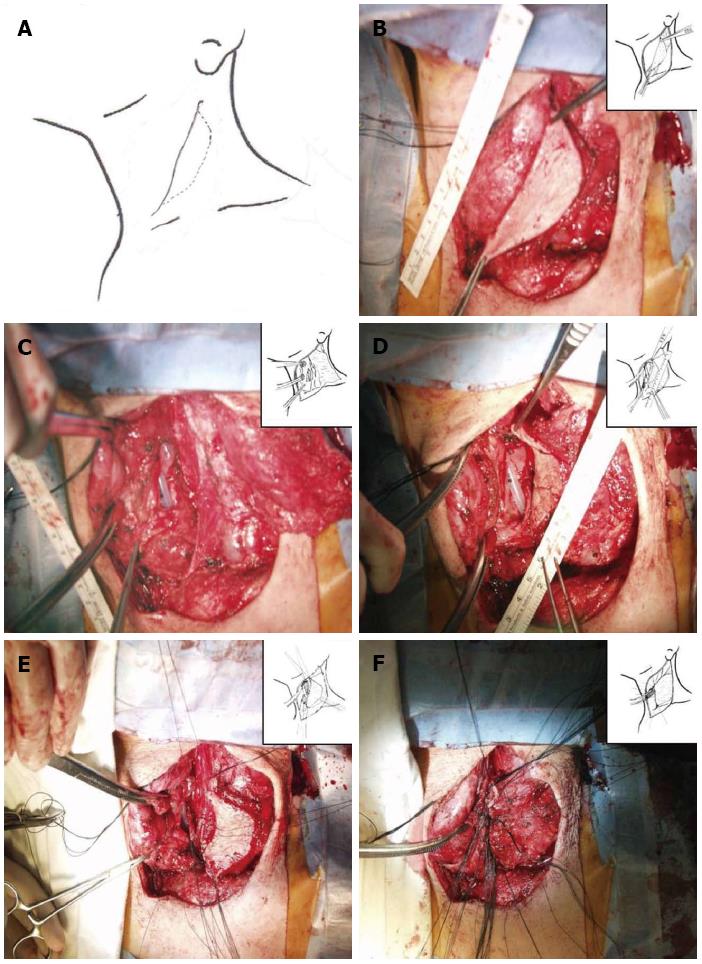

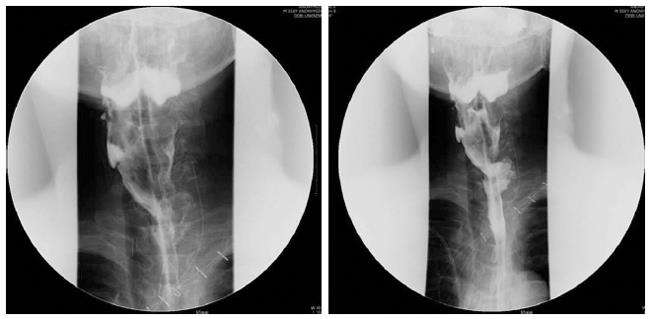

A 53-year-old male developed recurrent cervical esophageal stenosis 1.5 years after undergoing esophageal bypass surgery using a right colon conduit. He had received corrosive esophageal strictures three years earlier after a suicide attempt by potassium hydroxide ingestion. His presentation was complicated, with multi-level stenotic segments down the entire esophagus. He underwent repeated balloon dilatation, but one cervical stricture progressed to near-complete obstruction just below the entrance of the esophagus as seen on endoscopy and barium esophagogram. The severity of stenosis below the proximal esophagus could not be evaluated. He had severe weight loss of 15 kg and required total parenteral nutrition, afterwards gaining back about 2.5 kg (43 kg and 173 cm, body mass index 14.37). Instead of feeding gastrostomy insertion, esophageal bypass surgery using a segment of the right colon was performed one year later. At surgery, the ileum was anastomosed with the cervical esophagus in a side-to-end manner, and its blood supply was preserved. Postoperative esophagogram showed that barium passed through the native esophagus and newly constructed colon conduit. The patient began to eat 7 d after surgery and returned home 14 d after surgery with a weight gain of 3 kg. On follow-up, he gained weight by additional 3 kg, but suffered from painful swallowing of solid food three mo after discharge. Follow-up endoscopy revealed cicatricial stenosis in the native esophagus proximal to the interposed colon, though the site of gastro-colon anastomosis was patent. Barium esophagogram showed mild stenosis at the level of the thoracic inlet and severe stenosis just above the anastomosis of the esophagus. The patient underwent repeated 7 times esophageal dilatation using Savary-Guillard or balloon dilators, and an episode of electrocauterization ablation to improve swallowing before the 2nd operation. Despite endoscopic dilatation using electrocauterization, he again developed pain on swallowing. Finally, he was admitted for surgical correction. We reviewed the esophagogram and endoscopic findings (Figure 1). The stenotic segment was 3 cm long and located in the proximal esophagus near the site of the previous esophago-colonic anastomosis. Fortunately, the lesion was easily opened with a dilator or balloon. This finding suggested that the stenotic segment was not caused by mechanical stenosis resulting from circumferential fibrosis, but was caused by twisted axis of esophageal anastomosis site possibly due to cicatricial obstruction resulting from colon conduit failure. We planned to perform a patch enlargement operation with a myocutaneous flap of SCM muscle. Under endotracheal anesthesia, the patient was placed supine with neck extension and slight rotation for better exposure. A skin incision in the neck was made along the previous incision while preserving an elliptical skin island over the SCM muscle (Figure 2). Improved exposure of the stenotic cervical esophagus was obtained after SCM division with a skin island near the clavicle. There was a fibrotic band near the proximal esophagus instead of near the colon. The proximal esophagus and hypopharynx were exposed, and a small esophagotomy at the level of the cricoid cartilage was initially made and extended upward to the hypopharynx with a longitudinal incision of about 5 cm (Figure 2). The attached skin island of the SCM myocutaneous flap was rotated medially over the esophago-pharyngeal opening and sutured in interrupted fashion with 3-0 black silk. The SCM muscle attached to the skin flap was then tacked into place around the esophagus and pharynx. A drain was placed, and the neck wound was closed after a skin tension-releasing procedure (Figure 2). Seven days later, an esophagogram showed good passage without tracheal aspiration (Figure 3). The patient could eat a solid meal without pain or resistance and returned home in ten days. He then returned to work and has been well with a gradual weight gain about 10 kg for 18 mo after the esophagoplasty.

Graft necrosis is the most dangerous complication of colon graft interposition with a reported mortality approaching 90% or more[3]. Most instances of colonic graft ischemia are secondary to arterial insufficiency[3]. Ischemic complications are expressed as frank colon necrosis, anastomotic leakage, and colonic stricture[3]. Colonic segment necrosis and anastomotic leakage usually occur in the first postoperative week[4], but in our case, localized strictures of the cervical region developed 1.5 years after the first bypass operation. The slow course is likely explained by slowly progressive ischemia from graft torsion, resulting in a non-necrotic colonic cicatricial stricture rather than colonic necrosis. This may be the cause of esophageal obstruction in our case. This cicatricial change in the esophageal anastomosis site might twist the esophageal axis, and cause painful swallowing. Also this lesion was easily dilated with esophageal ballooning.

Although dilatation is the primary method of treating esophageal strictures[5], alimentary tract reconstruction is necessary for correction of severe and extensive strictures. Invasive surgeries like stomach pull-up, colon bypass, and free jejunal flap are not always possible when the prior operation was similarly invasive[6].

In our case, the right colon had already been used during the previous bypass operation, and the graft stricture of the neo-esophagus resulted from ischemia. Thus, patch dilative strictureplasty with viable tissue was thought to be an ideal option for relieving the short, benign, recurrent cervical esophageal stricture.

The choice of tissue to be used as a patch to widen the esophagus varies. Among flaps, a myocutaneous flap has several advantages: its skin provides an adequate patch for the esophageal defect and the well-vascularized muscle forms a seal around the ischemic anastomosis site, obliterates dead space, and conveys antibiotics[7]. The SCM muscle is a logical choice for myocutaneous flap in this case because its anatomic proximity lessens trauma[7]. Because SCM patch esophagoplasty avoids complete transection of the esophagus, coordinated peristalsis is also preserved and vagotomy is avoided[7]. The SCM muscle has a segmental blood supply from branches of three main vessels: the occipital artery superiorly, the superior thyroid artery in the middle segment, and a branch of the thyrocervical trunk inferiorly. The superior pedicle is more commonly used because it provides greater rotation and allows the SCM to reach the entire length of the ipsilateral cervical esophagus[2]. The SCM myocutaneous flap does, however, have limitations. Safety is a major concern when the SCM flap is used in oncologic patients[8]. In cases of radiation therapy, the SCM myocutaneous flap may be used only if the overlying skin is soft and supple[2]. Furthermore, use of a SCM pedicled skin flap is limited to the cervical esophagus. In conclusion esophagoplasty with SCM myocutaneous flap is thought to be an efficient treatment of recurrent cervical esophageal strictures.

P- Reviewer Roman S S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Park JK, Sim SB, Lee SH, Jeon HM, Kwack MS. Pharyngo-enteral anastomosis for esophageal reconstruction in diffuse corrosive esophageal stricture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:1141-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Noland SS, Ingraham JM, Lee GK. The sternocleidomastoid myocutaneous “patch esophagoplasty” for cervical esophageal stricture. Microsurgery. 2011;31:318-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wormuth JK, Heitmiller RF. Esophageal conduit necrosis. Thorac Surg Clin. 2006;16:11-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jain V, Rodrigues GS, Gupta K. Ischaemic necrosis of subcutaneous colonic neoesophagus: an unusual complication of presternal hypertrophic scar. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:235-236. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ananthakrishnan N, Parthasarathy G, Maroju NK, Kate V. Sternocleidomastoid muscle myocutaneous flap for corrosive pharyngoesophageal strictures. World J Surg. 2007;31:1592-1596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin YD, Jiang YG, Wang RW, Gong TQ, Zhou JH. Platysma myocutaneous flap for patch stricturoplasty in relieving short and benign cervical esophageal stricture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1090-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cunningham DK, Stern SJ, Burnett HF. Sternocleidomastoid myocutaneous esophagoplasty for benign cervical stricture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1406-1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lin CH, Lin CH, Wu CW, Liao CT. Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap: an option to seal off the esophageal leakage after free jejunal flap transfer--a case report. Chang Gung Med J. 2009;32:224-229. [PubMed] |