Published online Jan 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.299

Revised: October 30, 2012

Accepted: November 6, 2012

Published online: January 14, 2013

Processing time: 148 Days and 9.7 Hours

Ischemic colitis accounts for 6%-18% of the causes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. It is often multifactorial and more commonly encountered in the elderly. Several medications have been implicated in the development of colonic ischemia. We report a case of a 54-year old woman who presented with a two-hour history of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and bloody stool. The patient had recently used lubiprostone with close temporal relationship between the increase in the dose and her symptoms of rectal bleeding. The radiologic, colonoscopic and histopathologic findings were all consistent with ischemic colitis. Her condition improved without any serious complications after the cessation of lubiprostone. This is the first reported case of ischemic colitis with a clear relationship with lubiprostone (Naranjo score of 10). Clinical vigilance for ischemic colitis is recommended for patients receiving lubiprostone who are presenting with abdominal pain and rectal bleeding.

- Citation: Sherid M, Sifuentes H, Samo S, Deepak P, Sridhar S. Lubiprostone induced ischemic colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(2): 299-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i2/299.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.299

Ischemic colitis in patients with nonocclusive vascular disease is thought to result from a transient low flow state through an inadequate vascular system. Advanced age, aortic surgery, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease have been also suggested to be predisposing factors for ischemic colitis[1]. It occurs more often in the splenic flexure and rectosigmoid junction which are known as the watershed areas. These areas are the distributions of the superior mesenteric artery and the inferior mesenteric artery for the splenic flexure and between the inferior mesenteric artery and the internal iliac artery for the rectosigmoid junction[1].

The pathophysiology of developing ischemic colitis includes transient hypoperfusion that involve segments of the colon. Affected patients are often elderly or have a cardiovascular condition (congestive heart failure or an arrhythmia) which puts them at risk to develop a transient reduction in bowel perfusion. Less common causes of ischemic colitis include hypercoagulable states, vasculitis, embolus, colonic obstruction (strictures, colon cancer, diverticulitis)[1,2]. Other causes include medications and substances such as amphetamines, alosetron, catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine), cocaine, digitalis, nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs, pseudoephedrine and triptans, etc[3].

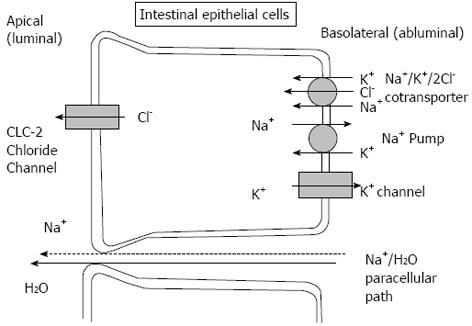

Lubiprostone was initially approved in 2006 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of idiopathic chronic constipation at a dose of 24 mcg twice daily[4-6]. In 2008, it was approved for women with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome at dose of 8 mcg twice daily[4,5,7]. Lubiprostone is a prostaglandin E1 derivative which acts by activating chloride channel type-2 (CLC-2) in the apical membrane of the intestinal epithelial cells. Consequently, it produces chloride rich fluid into the intestinal lumen with a passive sodium and water shift which increases the liquidity of the stool and promotes the gastrointestinal tract motility which in turn accelerates the bowel transit[8]. Lubiprostone acts locally on the bowel epithelium and is minimally absorbed. It is well known to cause nausea, diarrhea, abdominal distention, and abdominal pain. Here we describe the first case report of ischemic colitis associated with lubiprostone usage.

A 54-year old female presented with a two-hour history of nausea, non-bloody, non-bilious vomiting associated with crampy generalized abdominal pain located to the epigastrium and left upper quadrant. She did not have any bowel movements 3 d prior to her presentation. In the emergency department, she had one bowel movement with hard stool followed by 6 watery, bloody stools. She did not have a fever or urinary symptoms. She did not have a history of recent antibiotic use, travel outside the United States, recent diet changes, or history of symptoms suggestive of inflammatory bowel disease. She suffers from diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, hypothyroidism and chronic constipation. Her current medications included metformin (taking for 8 years), lisinopril (taking for 3 years), atorvastatin (taking for 4 years) and replacement thyroxin (taking for 4 years). She did not smoke or use illicit drugs.

On admission, her vital signs were essentially normal with a blood pressure of 134/70 mmHg without orthostatic changes, a heart rate of 61 bpm, temperature of 97.7 F°, respiratory rate of 16/min, oxygen saturation of 97% on room air, height of 162 cm, weight of 60.8 kg, and body mass index of 23.2. She did not have any episodes of hypotension either in the emergency department or during her hospitalization. Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with mild epigastric and left upper quadrant tenderness. There was no distension, guarding, rebound tenderness, or organomegaly. The bowel sounds were normal. Rectal exam was unremarkable except for positive occult blood. The remainder of physical exam revealed no findings.

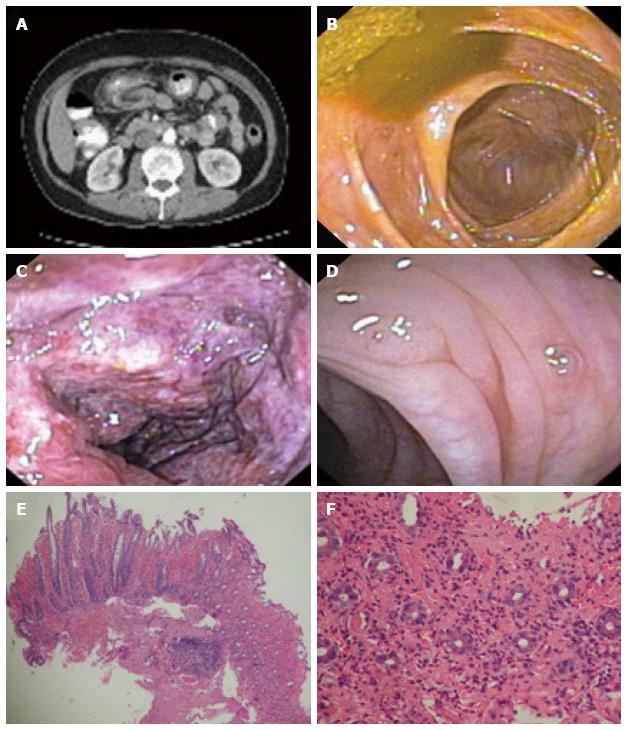

The laboratory studies were unremarkable including complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, amylase, lipase, urinalysis, and urine toxicology. The stool studies were negative for ova, parasites, clostridium difficile, and pathogenic bacteria. The hemoglobin A1c was 6.5%. A plain abdominal X-ray was unremarkable. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed thickening of the colonic wall involving the transverse and the proximal portions of the descending colon near the splenic flexure (Figure 1A). A colonoscopic examination showed mucosal changes consistent with ischemic colitis (mucosal edema and hyperemia with areas of hemorrhage, erosions, and frank ulcerations) affecting the descending colon, between 30 to 40 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1B-D). The histopathology examination showed ischemic loss of crypts with acute hemorrhage in lamnia propria associated with acute fibrinopurulent exudate at colonic epithelial surface, consistent with ischemic colitis (Figure 1E, F).

A diagnosis of ischemic colitis was made based on the above findings. To clarify the etiology, a detailed history was taken including the use of over the counter and herbal medications. She stated that she had been taking lubiprostone for a period of 2 mo prior to her admission after she failed to respond to conventional laxatives for chronic constipation. The patient was initially started on 24 mcg of lubiprostone, but several hours after taking the drug, she developed nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain with bloody diarrhea which lasted for two days. She did not undergo any investigations, but her dose of lubiprostone was changed to 8 mcg daily as needed after she called her primary care physician. Twenty-four hours prior to her current admission she had taken a total of 24 mcg of lubiprostone. Her symptoms developed two hours after the last dose. This temporal relationship between the recurrence of her symptoms and the rechallenging of the drug confirms the diagnosis of ischemic colitis in the light of absence of other causes of ischemic colitis. This case scored a 10 on the Naranjo Nomogram for adverse drug reactions which places lubiprostone as a definitive cause of ischemic colitis in this case (definitive ≥ 9). The patient was treated with discontinuation of lubiprostone, intravenous fluids, bowel rest and intravenous antibiotics. Her hospitalization course was uneventful and she was discharged home without any complications 4 d later.

Ischemic colitis accounts for 6%-18% of the causes of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding[2]. The causes of ischemic colitis vary from systemic hypotension, aortoiliac surgery, atherosclerosis, thromboembolic events, vasculitis, and medications[9].

The medications that have been implicated in the development of ischemic colitis have different mechanisms including decreasing blood flow via systemic hypotension with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, vasospasm with pseudoephedrine, thromboembolic events with oral contraceptives, vasculitis secondary to gold salts, and increasing intracolonic pressures with alosetron[3]. The mechanism of some drugs reported to cause ischemic colitis has not yet determined. Table 1 shows a list of medications and their mechanisms for causing ischemic colitis[3].

| Agent | Mechanism |

| Amphetamines | Vasoconstriction |

| Alosetron | |

| Catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine) | |

| Cocaine | |

| Cyclosporine | |

| Digitalis | |

| Dopamine | |

| Ergot derivatives | |

| Nonsteriodal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Pseudoephedrine | |

| Triptans (Naratriptan, Rizatriptan, Sumatriptan) | |

| Vasopressin and vasopressin analogues | |

| Glycerin enema | Local vasospasm effect |

| Phosphosoda solution | |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Systemic hypotension |

| Antipsychotic (chlorpromazine) | |

| Beta blockers | |

| Barbiturates | |

| Diuretics | |

| Interleukin-2 | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |

| Amphetamines | Vasculitis |

| Gold compounds | |

| Estrogens | Thrombotic lesion induction |

| Progestational agents | |

| Alosetron | Increased intracolonic pressure |

| Danazol | |

| Glycerin enema | |

| Carboplatin | Undetermined |

| Flutamide | |

| Glutaraldehyde | |

| Hyperosmotic saline laxatives | |

| Interferon-alpha | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | |

| Paclitaxol | |

| Simvastatin | |

| Tegaserod | |

Many case reports have linked ischemic colitis and other unusual associations such as herbal remedies (ma huang/ephedra), weight loss medications such as phentermine, following screening colonoscopies, certain chemotherapy agents such as bevacizumab and irinotecan, hepatitis C therapy with peginterferon and ribavirin, scuba diving, flying, snake bites, acute carbonic monoxide poisoning, using electrical muscle stimulation devices on the abdominal wall, and following long distance running[3].

Lubiprostone has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. In a 48 wk prospective, multicenter, open-labeled trial performed by Lembo et al[10] patients with chronic idiopathic constipation were taking lubiprostone 24 mcg twice daily as needed and the most common side effects were nausea (19.8%), diarrhea (9.7%), abdominal distension (6.9%), headache (6.9%), and abdominal pain (5.2%).

Lubiprostone has also been approved for the treatment of constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C). In a randomized, placebo controlled trial, the overall rate of response based on a patient ranked assessment tool was significantly higher in the lubiprostone group using 8 mcg twice daily compared to placebo. The side effects were similar in both groups[11].

In a phase 2, placebo controlled trial by Johanson et al[12] lubiprostone was superior to placebo in IBS-C regarding the severity of constipation, stool consistency, frequency, straining, bloating, and abdominal pain in 1, 2, and 3 mo follow ups. Both diarrhea and nausea occurred more often in the lubiprostone group, especially with 24 mcg twice daily compared to 8 mcg twice daily.

Lubiprostone is a bicyclic fatty acid, derived from prostaglandin E1. It is a member of a class of drugs called prostones which, unlike prostaglandins, are not believed to cause direct smooth muscle contraction. It is metabolized in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract by the microsomal carbonyl reductase system. Lubiprostone acts locally in gastrointestinal epithelium and its active metabolite, M3, absorbs systemically. The half-life of M3 is 0.9-1.4 h. M3 is used for the pharmacokinetic parameters of lubiprostone because the drug itself has limited systemic absorption and low bioavailability[4,8].

Lubiprostone mainly acts on CLC-2 activators in the intestinal epithelium which is one of the nine types of chloride channels in the body which also includes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (Figure 2)[13].

Activation of CLC-2 in the apical membrane of intestinal epithelial cells causes an active secretion of chloride ions from cells into the intestinal lumen followed by a passive secretion of sodium ions and water which results in increased isotonic fluid in the lumen which promotes small bowel and colonic transit by stimulating stretch receptors and smooth muscles in the intestine (Figure 2)[8].

There is now controversy whether lubiprostone activates CLC-2 in be basolateral or apical aspect of intestinal epithelium, whether it activates mainly CFTR or CLC-2, or whether it directly stimulates smooth muscles via prostaglandin receptors[8]. Bao et al[14] showed in an experimental study that lubiprostone activates CLC-2 at low concentrations but activates CFTR at higher concentrations. It has also been shown that lubiprostone weakly activates prostaglandin receptors in different levels of the GI tract which could be responsible for some side effects such as nausea[15].

In our patient, despite having other risk factors for ischemic colitis such as chronic constipation which has been shown to increase the risk of ischemic colitis by 2.7 folds in some studies[16], the close temporal relationship between lubiprostone and occurrence of the symptoms of ischemic colitis makes the drug the most likely culprit of this event. When applying the Naranjo Nomogram in our patient, a score of 10 was obtained indicating a definite likelihood of lubiprostone as the cause of ischemic colitis in this case (Table 2).

| Yes | No | Our patient | |

| Are there previous conclusive reports on this reaction? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Did the adverse event appear after the suspected drug was administered? | 2 | -1 | 2 |

| Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued or a specific antagonist was administered? | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Did the adverse reaction reappear when the drug was readministered? | 2 | -1 | 2 |

| Are there alternative causes (other than the drug) that could have, on their own, caused the reaction? | -1 | 2 | 2 |

| Did the reaction appear when a placebo was given? | -1 | 1 | 1 |

| Was the drug detected in the blood (or other fluids) in concentration known to be toxic? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased or less severe when dose was decreased? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure? | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence? | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of lubiprostone induced ischemic colitis. We report that a direct causal relation by exclusion of other causes, the disappearance of symptoms after cessation of lubiprostone, recurrence of symptoms with self rechallenge, and a Naranjo Nomogram score of 10 all go in favor of the drug-induced ischemic colitis. The actual mechanism of lubiprostone causing ischemic colitis is not known, however, fast fluid shift into the intestinal lumen causing local hypoperfusion, rapid increase of the intracolonic pressure due to rapid fluid secretion into the bowel, or direct vasoconstriction caused by lubiprostone in higher doses by stimulating prostaglandin receptors are the proposed pathophysiological mechanisms. In conclusion, lubiprostone may cause ischemic colitis, especially in some susceptible persons and greater awareness of this side effect is warranted with the increasing use of lubiprostone.

P- Reviewers King TM, Chung WC S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Theodoropoulou A, Koutroubakis IE. Ischemic colitis: clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7302-7308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:643-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sherid M, Ehrenpreis ED. Types of colitis based on histology. Dis Mon. 2011;57:457-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | AMITIZA® (lubiprostone) [package insert]. Bethesda, MD: Sucampo Pharmaceuticals. 2009;. |

| 5. | Schiller LR, Camilleri M. Lubiprostone: viewpoints. Drugs. 2006;66:880-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ford AC, Suares NC. Effect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2011;60:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lang L. The Food and Drug Administration approves lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lunsford TN, Harris LA. Lubiprostone: evaluation of the newest medication for the treatment of adult women with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:361-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Stamatakos M, Douzinas E, Stefanaki C, Petropoulou C, Arampatzi H, Safioleas C, Giannopoulos G, Chatziconstantinou C, Xiromeritis C, Safioleas M. Ischemic colitis: surging waves of update. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;218:83-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lembo AJ, Johanson JF, Parkman HP, Rao SS, Miner PB, Ueno R. Long-term safety and effectiveness of lubiprostone, a chloride channel (ClC-2) activator, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2639-2645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, Fass R, Scott C, Panas R, Ueno R. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome--results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johanson JF, Drossman DA, Panas R, Wahle A, Ueno R. Clinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:685-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lipecka J, Bali M, Thomas A, Fanen P, Edelman A, Fritsch J. Distribution of ClC-2 chloride channel in rat and human epithelial tissues. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C805-C816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bao HF, Liu L, Self J, Duke BJ, Ueno R, Eaton DC. A synthetic prostone activates apical chloride channels in A6 epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G234-G251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bassil AK, Borman RA, Jarvie EM, McArthur-Wilson RJ, Thangiah R, Sung EZ, Lee K, Sanger GJ. Activation of prostaglandin EP receptors by lubiprostone in rat and human stomach and colon. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:126-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Suh DC, Kahler KH, Choi IS, Shin H, Kralstein J, Shetzline M. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome or constipation have an increased risk for ischaemic colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:681-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |