INVITED COMMENTARY ON HOT ARTICLES

Juan Rosai’s Surgical Pathology (9th edition) contains 45 pages on the small intestine, compared with 80 pages on the large intestine[1]. The actual length of the small intestine is much longer than that of the large intestine, and the vital importance of the small intestine is well known. Why then are fewer pages devoted to diseases of the small intestine? Obviously, the access of surgical pathologists and gastroenterologists to the small intestine is limited, compared with access to the large intestine and appendix. Actually, the old version of Morson and Dawson’s textbook Gastrointestinal Pathology[2] is fairer: the same number of pages is devoted to the small intestine and to the large intestine, probably because this book is a product of the century during which autopsies made major contributions to our knowledge base. This issue of the World Journal of Gastroenterology has a wide-ranging review article on the pathophysiology of the small intestine by Professor Basson and his colleagues[3]. These authors are surgeons, and a tremendous amount of data based on their own clinical experiences and those of others, as well as on animal experiments, are comprehensively discussed in their review. This review article addresses conditions such as starvation and parenteral nutrition in patients with severe trauma or pancreatitis and in patients with postoperative short-gut syndrome for various reasons including bariatric surgery for obesity. Although these conditions are undoubtedly serious, recognition and explicit statements by medical professionals regarding the importance of the small intestine, and of its diseases as a “great burden of human distress”, have only recently appeared in medical literature[4]. Most clinical conditions that highlight the importance of the small intestine are familiar only to experts in a particular area of medicine. These conditions are not typically a concern of non-surgical gastroenterologists, such as pathologists who are accustomed to diagnosing neoplasms of the large intestine, grading inflammatory bowel disease, and validating ischemic necrosis of the resected small intestine in cases with an acute abdomen. The small intestine is most often investigated because of its involvement in a disease originating from another organ, such as the mesothelium[5]. Changes in the mucosa of the small intestine itself are an exceptional category among the slides that pile up next to the microscope.

The situation is now changing. As avid readers of World Journal of Gastroenterology may have noticed[6-9], recent progress in enteroscopy has enabled areas deep within the small intestine to be reached, providing clinicians active in the wider branches of gastroenterology with the opportunity to evaluate changes in the small intestine, which have previously only been observed by surgeons. This also means that many non-surgeons must commit to the management of the small intestine, based on findings and evaluations associated with specimens of small intestine obtained using these newly developed modalities. For ordinary pathologists, for example, the concepts mainly discussed in this review, i.e., adaptation and atrophy of the small intestine, may be new and unfamiliar. These lesions were encountered only after specific “congenital or acquired disease or medical and surgical intervention” had occurred in the patients. When specimens obtained by enteroscopy become routine in the future, however, the concepts and knowledge of adaptation and atrophy of the small intestine will become an essential “must” for all practitioners including general pathologists.

One of the important conditions that the authors of this review addressed is the change in the small intestine in subjects receiving total parental nutrition. This lifesaving modality has many variations in terms of its nutritional regimen and the effects of these variations on pathophysiology, that is, on the grade of adaptation of the small intestine. These effects on the small intestinal mucosa and the consequent outcomes of individual patients have been thoroughly investigated and published in many scientific articles, but the scientific evidence in human beings remains insufficient according to the above-mentioned authors. The concept of mucosal adaptation[10] includes proliferation, functional augmentation, and cellular differentiation. Biochemical changes include alterations in molecules related to apoptosis, proliferation, signal transduction, and fatty acid metabolism. These meticulous frameworks in intestinal cells and tissues have so far been revealed by studies using in vivo and in vitro manipulative systems. From now on, in the era of enteroscopy, lingering questions such as “what is the reality and examples of mucosal adaptation in human clinical settings?” and “how can we validate the accumulated experimental findings in human beings and exploit them in clinical practice?” will be answered.

Small intestinal enteroscopy is now available in ordinary hospitals, thus facilitating the detection of previously unobserved pathological conditions. Capsular endoscopy, the latest wireless version of enteroscopy, has become a popular practical procedure since the publication of a seminal report on this modality a decade ago[11]. In the minds of laymen, this technique seems like a dream[12]. The use of capsular endoscopy and refined enteroscopy using a double-balloon method[13] in clinical practice have revealed thousands of new anecdotal findings (Figure 1), and the rapid accumulation of this kind of basic knowledge of the small intestine will help to set up principles of surveillance for mucosal adaptation and atrophy of the small intestine (especially morphological changes) in various clinical conditions. For example, introduction of capsular endoscopy and a double-balloon method disclosed previously unrecognized lesions such as adenocarcinoma arising from Crohn disease in the small intestine (Figure 2)[14], submucosal lipoma (Figure 3), tuberculosis at the terminal ileum (Figure 4), and angioectasia (Figure 5). None of these lesions were accessible until the recent development of capsule endoscopy and the double balloon method. The morphology is new to pathologists and endoscopists, and these developments will critically influence the managements of the patients. The concepts that Professor Basson and colleagues have illuminated in their review will soon become an important guidepost for evaluating the histopathology of the small intestine in daily practice and for patient care by a broader range of gastroenterologists.

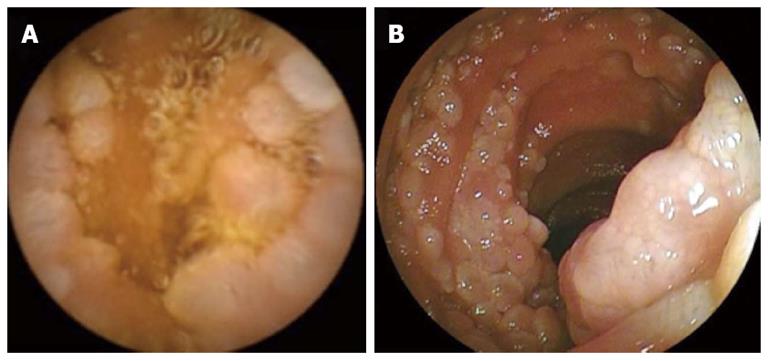

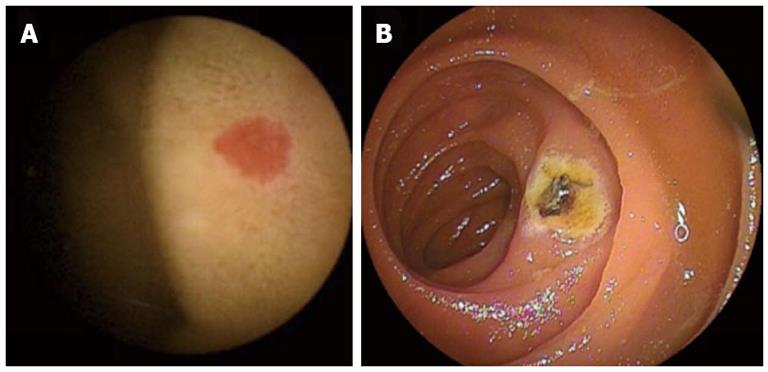

Figure 1 Endoscopy.

Images obtained using capsule endoscopy (A) and double-balloon enteroscopy (B) in a 61-year-old man with follicular lymphoma who visited us because of gastrointestinal bleeding from an unknown cause and a hemoglobin concentration of 9.7 g/dL.

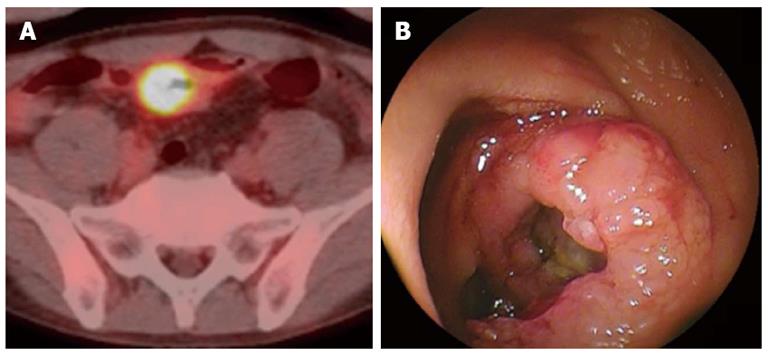

Figure 2 A mass positive by positron emission computed tomography actually was a tumor arising the mucosa of the small intestine of a 48-year-old woman who had suffered Crohn disease.

A: Positron emission computed tomography/computed tomography showed an accumulation in site of wall thickening of ileum; B: Image obtained by double-balloon enteroscopy.

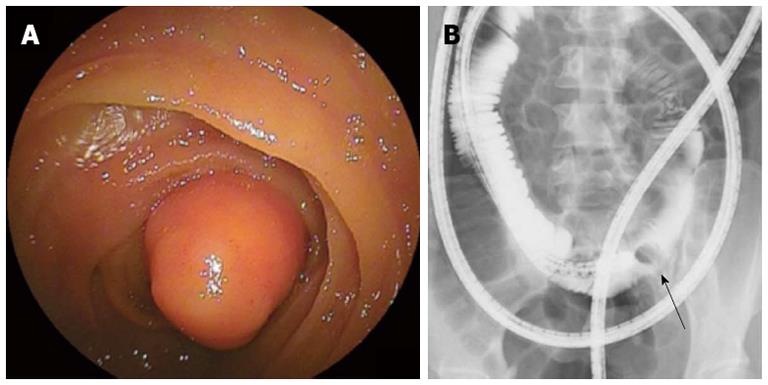

Figure 3 Identification of lipoma clarified the reason of intermittent abdominal discomfort in a 29-year-old female.

Endoscopic finding (A) and selective small bowel series (B) obtained using double-balloon enteroscopy. This required surgical intervention. An arrow in the B indicates a defect by a lipoma.

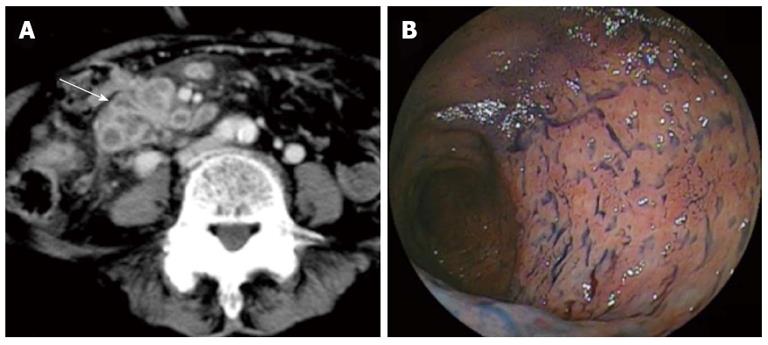

Figure 4 Intestinal tuberculosis is also revealed by double-ballon enteroscopy.

A: Computed tomography showed wall thickening of the ileum with contrast enhancement (arrow); B: Double-balloon enteroscopy showed destruction of the small intestinal villi.

Figure 5 Angioectasia.

A: Diagnosis of angioectasia was made by capsule endoscopy; B: Argon plasma coagulation successfully treated the lesion.