Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2574

Revised: January 3, 2013

Accepted: January 17, 2013

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 150 Days and 10.4 Hours

Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) with intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage is a very rare clinical condition. There has been no report of HSP complicated with both intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage until October 2012. Here we describe a case of HSP with intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage in a 5-year-old girl. Plain abdominal radiograph in the erect position showed heavy gas in the right subphrenic space with an elevated diaphragm. Partial resection of the small intestine was performed, and pathological analysis suggested chronic suppurative inflammation in all layers of the ileal wall and mesentery. Seventeen days after surgery, cerebral hemorrhage developed and the patient died.

- Citation: Wang HL, Liu HT, Chen Q, Gao Y, Yu KJ. Henoch-Schonlein purpura with intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2574-2577

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2574.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2574

Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP), also known as anaphylactoid purpura, is the most common form of systemic vasculitis in children[1]. It occurs most commonly in children between 3 and 10 years old[2] and affects small vessels. Typical symptoms of HSP include palpable purpura, arthralgia, stomach ache and hematochezia. Pathologically, HSP is characterized by the development of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in small vessels with deposition of immune complexes mainly consisting of immunoglobulin A. Although the etiology is still unclear, HSP is known to develop after upper respiratory infection or drug allergy[3] and is therefore considered an autoimmune disease. It is reported that the incidence of HSP with intestinal perforation is 0.38%, mainly affecting the ileum and occasionally the jejunum, where intestinal perforation appears about 10 d after the onset of initial symptoms[4]. The incidence of HSP with central nervous system symptoms is between 0.9% and 6.9%, and HSP with intracranial hemorrhage has an even lower incidence[5]. The most common sign of HSP with intracranial hemorrhage is seizure, followed by headache, changes in mental status, and focal neurologic deficits[6]. To date, there have been only 10 reported cases of HSP with cerebral hemorrhage. Herein we report a case of HSP with intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage.

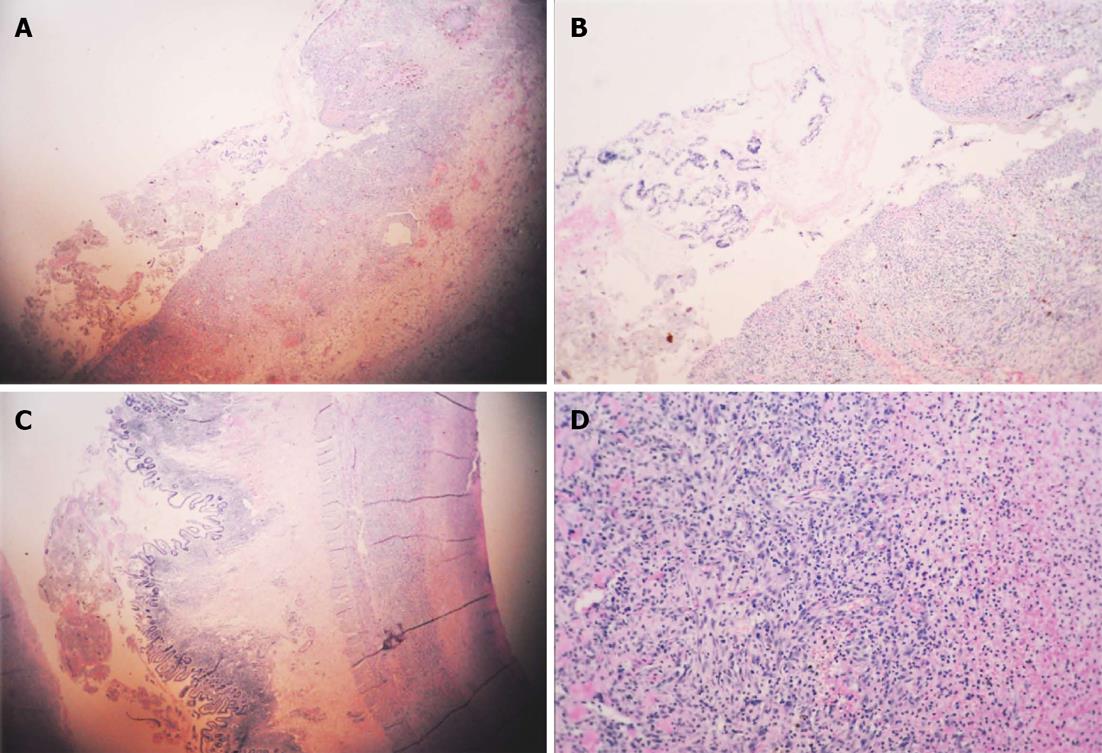

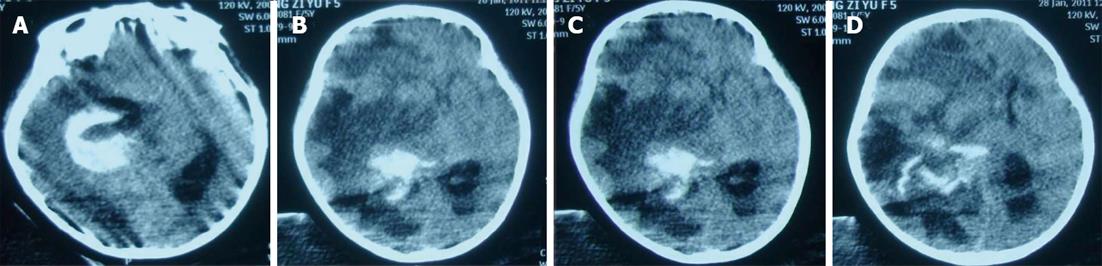

A 5-year-old Chinese girl was admitted to our intensive care unit with complaints of abdominal pain for 22 d, rash for 21 d, and hematuria for 2 wk. She was previously healthy and had a history of allergy to aminopyrine. Upon physical examination, her general condition was poor. Her blood pressure was 112/69 mmHg, heart rate 153 beats/min, body temperature 37.2 °C, and arterial oxygen saturation 87%. She was unconscious and presented with difficulty breathing, cyanotic lips, rales, abdominal bulge (Figure 1), marked abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness and muscle tension, and marked edema of the bilateral lower extremities up to the level of her knees. She had purpuric papules, 1-2 cm in diameter, over her ankles, buttocks and lower legs, as well as raised flesh-colored papules over her upper medial legs, but her upper trunk and perineum were not involved. Neurologic exam was within normal limits. Laboratory data on admission were as follows: white blood cell count 45900/μL with an increase in the percentage of neutrophils (93.5%); hemoglobin 69 g/L; hematocrit 20.9%; platelet count 40000/L; prothrombin time 10.6 [international normalized ratio (INR) 0.99]; serum total protein 33 g/L; albumin 12 g/L; cholinesterase 223 U/L; alkaline phosphatase 128 U/L; urea 15.3 mmol/L; serum creatinine 84.0 μmol/L; urine protein 2+; and urine occult blood 5+. Cerebral and chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated slight widening of cerebral sulci and cisterns, inflammation of the lungs, and bilateral pleural effusions. Plain abdominal radiograph in the erect position showed heavy gas in the right subphrenic space with an elevated diaphragm (Figure 2). Abdominal ultrasonography showed remarkable intestinal expansion in the lower abdomen and increased bilateral renal artery resistance index. To improve the patient’s condition, symptomatic treatments were given, including immediate intubation, mechanical ventilation, improvement of circulation, correction of disturbances of the internal environment, and application of broad-spectrum antibiotics. On January 13, the girl underwent emergency laparotomy. Intraoperative findings included necrosis of the intestine (10-30 cm long), with multiple perforations visible from the terminal ileum to the ileocecal valve, severe intestinal adhesion, and the presence of a large number of pus mosses on the surface of the liver, intestine and peritoneum. Surgical treatment strategies were enterectomy, enterostomy and peritoneal lavage. Postoperative pathological analysis suggested chronic suppurative inflammation in all layers of the ileal wall and mesentery (Figure 3). Thus, the patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicated by intestinal necrosis and perforation, nephritis, respiratory failure, and severe sepsis.

Postoperatively, comprehensive treatments were given, including broad-spectrum antibiotics, gamma-globulin, hormones, nutritional support, and mechanical ventilation. Following these treatments, the girl’s condition showed significant improvement: her inspired oxygen concentration was 40% and arterial oxygen saturation was 97%; the tension of the abdominal wall was reduced; and the surgical incision healed well. Apart from blood pressure (maintained at 130/90 mmHg) that was not controlled effectively by antihypertensive therapy, all other vital signs were satisfactory. Laboratory data after surgery were as follows: white blood cell count 24700/μL with an increased percentage of neutrophils (93.3%); hemoglobin 69 g/L; hematocrit 20.9%; platelet count 157000/L; prothrombin time 12 (INR 1.29); serum total protein 38 g/L; albumin 19 g/L; urea 13.2 mmol/L; serum creatinine 100 μmol/L; urine protein 2+; and urine occult blood 3+.

On January 28, the patient became unconscious suddenly and developed ptosis and mydriasis. Cerebral CT showed subarachnoid hemorrhage, right thalamic and intraventricular hemorrhage, and multiple ischemic changes in the left cerebellar hemisphere and bilateral cerebral hemispheres (Figure 4). Despite active rescue, the girl died on January 28.

HSP is a systemic vasculitis which affects small vessels, with typical symptoms including palpable purpura, arthralgia, stomach ache and bloody stools. Pathologically, HSP is characterized by the development of leukocytoclastic vasculitis in small vessels with deposition of immune complexes consisting mainly of immunoglobulin A[3]. Although all HSP patients invariably develop cutaneous purpura, other symptoms, such as arthritis, abdominal pain, and renal involvement, do not occur in all patients, which make the diagnosis of HSP more challenging[7]. In a few cases, HSP can affect other systems or organs and results in the occurrence of transient paralysis, convulsions, myocarditis, hypertension, and other symptoms[4]. Although palpable purpura is often considered the hallmark of HSP, skin findings were not described as the presenting feature in nearly 25% of patients[8].

Gastrointestinal manifestations are present in 45% to 75% of patients with HSP, with 14% to 36% of patients developing these symptoms prior to the appearance of purpura[9], as occurred in our case. After being treated with corticosteroids, gastrointestinal lesions in HSP are usually reversible and can heal, although a few patients (2%-6%) develop conditions requiring surgery[10]. It is reported that approximately 52% of HSP patients have varying degrees of gastrointestinal bleeding, mostly self-limiting; however, cases with serious intestinal bleeding (0%-8.2%) call for intervention, and misdiagnosis can be life-threatening[11]. Patients most commonly develop abdominal pain without complications. The most commonly reported complication is intussusception[12,13], while bowel ischemia and infarction, perforation, stricture, fistula, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, and appendicitis are infrequent. In our case, heavy gas in the right subphrenic space with an elevated diaphragm was detected radiographically, and surgical treatment strategies were enterectomy, enterostomy and peritoneal lavage. This observation may be of great clinical significance, as these gastrointestinal manifestations are usually serious and can result in invasive diagnostic techniques, including laparotomy. The incidence of HSP with central nervous system symptoms ranges from 0.9% to 6.9%, and HSP with intracranial hemorrhage has an even lower incidence[5]. The most common sign of HSP with intracranial hemorrhage is seizures, followed by headache, changes in mental status, and focal neurologic deficits. HSP as a form of necrotizing vasculitis results in a wide range of pathologic manifestations. According to the severity and site of the vascular lesions, diffuse encephalopathy, focal ischemia, or intracranial hemorrhages may develop[6,14]. With respect to the causes of cerebral hemorrhage in our case, the primary disease may play a major role because it can affect small vessels and lead to systemic vasculitis. Interestingly, we found the coexistence of cerebral ischemia and cerebral hemorrhage. It may be assumed that immunoglobulin A immune complex deposition initiates arteriolar inflammation in the cerebral vasculature as well as in the systemic vessels[12,14]. Cerebral hemorrhage was possibly secondary to resistant hypertension and cerebral vasculitis. Both purpura nephritis and increased bilateral renal artery resistance index could lead to resistant hypertension. In addition, cerebral hemorrhage might be associated with cerebral vascular malformation[5]; however, this possibility could not be ruled out in our case because of postoperative mechanical ventilation.

In conclusion, we herein describe a case of intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage secondary to HSP. Treatment of the primary disease is very important in preventing the occurrence of serious complications, such as intestinal perforation and cerebral hemorrhage. HSP patients should be closely monitored for early serious complications such as intestinal perforation and given timely surgery. Surgery is the most effective treatment. Despite its rarity, HSP should be considered when gastrointestinal perforation is observed. In addition, blood pressure should be controlled effectively in HSP patients to prevent the occurrence of serious neurological complications such as cerebral hemorrhage.

P- Reviewer Gregoire M S- Editor Song XX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Chen XL, Tian H, Li JZ, Tao J, Tang H, Li Y, Wu B. Paroxysmal drastic abdominal pain with tardive cutaneous lesions presenting in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1991-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dereli N, Ozayar E, Degerli S, Sahin S, Bulus H. A rare complication of Henoch-Schönlein Syndrome: gastrointestinal infarction and perforation. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2012;75:274-275. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hashimoto A, Matsushita R, Iizuka N, Kimura M, Matsui T, Tanaka S, Ishikawa A, Endo H, Hirohata S. Henoch-Schönlein pupura complicated by perforation of the gallbladder. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:441-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:598-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Misra AK, Biswas A, Das SK, Gharai PK, Roy T. Henoch-Schonlein purpura with intracerebral haemorrhage. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:833-834. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lewis IC, Philpott MG. Neurological Complications in the Schönlein-Henoch Syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1956;31:396-371. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | McCarthy HJ, Tizard EJ. Clinical practice: Diagnosis and management of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:643-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reamy BV, Williams PM, Lindsay TJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:697-704. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Choong CK, Beasley SW. Intra-abdominal manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chung DJ, Park YS, Huh KC, Kim JH. Radiologic findings of gastrointestinal complications in an adult patient with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W396-W398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein Purpura. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2011-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ostergaard JR, Storm K. Neurologic manifestations of Schonlein-Henoch purpura. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:339-342. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Katz S, Borst M, Seekri I, Grosfeld JL. Surgical evaluation of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Experience with 110 children. Arch Surg. 1991;126:849-853; discussion 853-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Belman AL, Leicher CR, Moshé SL, Mezey AP. Neurologic manifestations of Schoenlein-Henoch purpura: report of three cases and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1985;75:687-692. [PubMed] |