Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2521

Revised: December 12, 2012

Accepted: January 11, 2013

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 226 Days and 5.6 Hours

AIM: To assess the safety and efficacy of trans-arterial chemo-embolization (TACE) in very elderly patients.

METHODS: A prospective cohort study, from 2001 to 2010, compared clinical outcomes following TACE between patients ≥ 75 years old and younger patients (aged between 65 and 75 years and younger than 65 years) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), diagnosed according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases criteria. The decision that patients were not candidates for curative therapy was made by a multidisciplinary HCC team. Data collected included demographics, co-morbidities, liver disease etiology, liver disease severity and the number of procedures. The primary outcome was mortality; secondary outcomes included post-embolization syndrome (nausea, fever, abdominal right upper quadrant pain, increase in liver enzymes with no evidence of sepsis and with a clinical course limited to 3-4 d post procedure) and 30-d complications. Additionally, changes in liver enzyme measurements were assessed [alanine and aspartate aminotransferase (ALT and AST), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase] in the week following TACE. Analysis employed both univariate and multivariate methods (Cox regression models).

RESULTS: Of 102 patients who underwent TACE as sole treatment, 10 patients (9.8%) were > 80 years old at diagnosis; 13 (12.7%) were between 75 and 80 years, 45 (44.1%) were between 65 and 75 years and 34 (33.3%) were younger than 65 years. Survival analysis demonstrated similar survival patterns between the elderly patients and younger patients. Age was also not associated with the adverse event rate. Survival rates at 1, 2 and 3 years from diagnosis were 74%, 37% and 31% among patients < 65 years; 83%, 66% and 48% among patients aged 65 to 75 years; and 86%, 41% and 23% among patients ≥ 75 years. There were no differences between the age groups in the pre-procedural care, including preventive treatment for contrast nephropathy and prophylactic antibiotics. Multivariate survival analysis, controlling for disease stage at diagnosis with the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer score, number of TACE procedures, sex and alpha-fetoprotein level at the time of diagnosis, found no significant difference in the mortality hazard for elderly vs younger patients, and there were no differences in post-procedural complications. Serum creatinine levels did not change after 55% of the procedures, in all age groups. In 42% of all procedures, serum creatinine levels increased by no more than 25% above the baseline levels prior to TACE. Overall, there were 69 post-embolization events (23%). Hepatocellular enzymes often increased following TACE, with no association with prognosis. In 40% of the procedures, ALT and AST levels rose by at least 100%. The increases in hepatocellular enzymes occurred similarly in all age groups.

CONCLUSION: TACE is safe and effective in very elderly patients with HCC, and is not associated with decreased survival or increased complication rates.

- Citation: Cohen MJ, Bloom AI, Barak O, Klimov A, Nesher T, Shouval D, Levi I, Shibolet O. Trans-arterial chemo-embolization is safe and effective for very elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2521-2528

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2521.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2521

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the second cause of cancer-related deaths in men. It is the seventh most common cancer and sixth cause of cancer-related deaths among women[1]. The mean age of HCC diagnosis is increasing, and likewise the proportion of older patients seeking treatment for this deadly malignancy[2]. Latest estimates indicate that HCC incidence peaks above the age of 70 years[2,3].

Treatment modalities of HCC are limited. Curative treatment includes: liver resection, liver transplantation and, in small tumors, radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Only a small fraction of patients are eligible for these treatments. Most remaining patients receive palliative treatments including trans-arterial chemo-embolization (TACE), palliative RFA, sorafenib, or supportive care.

Compared to young patients with HCC, elderly patients have more co-morbidities and are considered poorer surgical candidates. Furthermore, patients older than 65-70 years of age are usually not considered to be potential candidates for liver transplantation[4]. Recently, sorafenib, the only proven chemotherapy to show efficacy against HCC, was evaluated in elderly patients (> 70 years), and was shown to have similar survival benefits as in patients younger than 70 years[5].

TACE has been previously shown to prolong survival among patients diagnosed with HCC who are not candidates for curative treatment. These data were recently challenged when a meta-analysis, using stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, did not demonstrate a survival benefit for TACE[6]. One limitation of that study was that most of the data were derived from case series and clinical trials which included patients who were younger than 65 years[7,8].

There are only a few studies which have assessed the role of TACE among elderly patients. Most of these studies defined elderly as patients over 70 years of age, including a Chinese cohort of 196 patients older than 70 years[9] and an Italian cohort of 158 patients[10]. In both studies, the majority of elderly patients were between 70 and 75 years of age.

Since 2000, we have prospectively enrolled patients in our HCC database. We noticed that our population is aging and includes patients in their late seventies, eighties and even nineties, seeking treatment. Our aim was to assess efficacy, survival and safety of TACE among very elderly patients defined as ≥ 75 years old, compared to younger patients in our cohort.

Local institutional board approval was received for this study, with waiver of the need for informed consent as identifying data were omitted after data collection and there was no intervention performed (HMO 0604-10). All patients diagnosed with HCC between 2000 and 2010 who underwent TACE were included and prospectively followed until January 2012. HCC diagnosis was determined in accordance with established guidelines published by both the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[11,12]. In cases where the radiological findings were inconclusive in establishing the diagnosis, percutaneous image-guided liver biopsy was performed. The decision that patients were not candidates for curative therapy was made by a multidisciplinary HCC team including the treating physician.

Demographic and clinical features were collected from patients’ medical records. Patients were designated into three cohorts, stratified by age at diagnosis (< 65 years of age, 65-75 years of age, ≥ 75 years of age). All patient data were collected using a national identification number.

Using a standard angiographic approach, transfemoral visceral arteriography was performed. Whenever possible, super selective TACE was attempted using a co-axial microcatheter and a mixture of 50 mg doxorubicin with lipiodol oil and gelfoam slurry or powder. If dictated by tumor burden and feasibility (hepatic reserve, Child Pugh status), segmental or lobar TACE was performed. Percutaneous vascular closure devices were routinely employed from 2007 onward.

All TACE procedures were recorded in the patient electronic records and all procedures were confirmed through the computerized hospital billing database. Inpatient notes and computer records were reviewed in order to extract clinical events, laboratory test results and medication provisions. The primary outcome of this analysis was overall mortality. Mortality rates and dates were determined via the national population registry. Secondary outcomes included post-embolization syndrome (nausea, fever, abdominal right upper quadrant pain, increase in liver enzymes with no evidence of sepsis and with a clinical course limited to 3-4 d post procedure); 30-d complications (sepsis, acute kidney injury, vascular events), as recorded in the medical charts; 30-d all-cause-readmission or all-cause-return to the emergency department. We also recorded pre-procedure (one week prior) and post-procedure (one week after) levels of creatinine, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase (ALT and AST), and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALKP). We cross-referenced clinical impressions documented in the medical files by examining all medical documents available to reduce bias resulting from human error and ascertainment bias.

Descriptive statistics were employed to presented age group characteristics. Categorical variables are depicted with percentages and distributions, and continuous variables are presented with mean ± SD. Associations between categorical variables were assessed with the Fisher exact test, and comparison of continuous variables was performed with the Student’s t-test, or with the Mann-Whitey U test. Survival charts were generated employing the Kaplan-Meier method, and survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. After confirming that the proportional hazard assumptions were met, we examined the association of age group with mortality using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Co-variables found on univariate analyses to have a seemingly probable association with mortality (P < 0.1) were included in the model. There were two types of missing data - treatment data and patient laboratory data. Treatments not specifically documented in the patient chart orders were considered not to have been provided (for example, preparation for contrast injection, antibiotic prophylaxis). In cases where laboratory tests were not taken, they were treated as missing and not included in the relevant analyses. In all analyses, two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We examined whether absolute and relative differences between pre-procedure and post-procedure laboratory tests were different between the age groups using one-way analysis of variance and plotted the relationship between these measures.

Between 2000 and 2010, 235 patients were diagnosed with HCC. Of these, 102 patients were treated with TACE alone. Thirty-day follow-up was complete (all living patients were evaluated in the liver clinic outpatient service) and survival follow-up was complete (none of the patients left the country and the population registry is updated regularly). Data collection was complete for laboratory data, and all patient files were available for clinical assessment.

We divided our population into 3 cohorts: age < 65 years (group 1), age between 65 and 75 years (group 2) and age ≥ 75 years (group 3). There were 38 patients in group 1, 41 patients in group 2 and 23 patients in group 3. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were 27 males and 75 females, with only three males in the younger age group. Younger patients had more advanced disease, as assessed by the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP), Okuda or Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging systems. The differences were less pronounced with the BCLC system, which accounts for functional status parameters, and we used this staging system to assess the primary outcome with multivariate analysis. Elderly patients had a mean alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level at diagnosis that was higher than the two other age groups. The distribution of the number of TACE procedures per patient was similar between the age groups.

| < 65 yr (n = 38) | 65-75 yr (n = 41) | ≥75 yr (n = 23) | P value | HR (95%CI) | |

| Age group multivariate HR (95%CI)1 | 1 | 1.03 (0.58-1.83) | 1.04 (0.56-1.9) | - | |

| Female | 35 (92.2) | 24 (58.6) | 16 (69.6) | 0.003 | 0.55 (0.31-0.98)1 |

| Cirrhosis at diagnosis | 35 (92.1) | 41 (1) | 22 (95.6) | 0.338 | |

| Ascites at diagnosis | 4 (10.5) | 4 (9.7) | 4 (17.3) | 0.632 | |

| Hepatitis B virus | 12 (31.5) | 7 (17.0) | 2 (8.6) | 0.06 | 0.85 (0.49-1.47)1 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 21 (55.2) | 29 (70.7) | 18 (78.2) | 0.14 | |

| Cancer of the Liver Italian Program2 | 0.008 | ||||

| 0 | 8 (21.0) | 20 (48.7) | 7 (30.4) | 1.9 (1.5-2.4)2 | |

| 1 | 6 (15.7) | 13 (31.7) | 9 (39.1) | ||

| 2 | 17 (44.7) | 8 (19.5) | 5 (21.7) | ||

| 3 | 6 (15.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.6) | ||

| 4 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Okuda2 | 0.001 | ||||

| 1 | 21 (55.2) | 39 (95.1) | 19 (82.6) | 5 (2.7-9.1)2 | |

| 2 | 16 (42.1) | 2 (4.8) | 4 (17.3) | ||

| 3 | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Child-Pugh-Turcot2 | 0.98 | ||||

| 1 | 31 (81.5) | 35 (85.3) | 19 (82.6) | 2.1 (1.2-3.6)2 | |

| 2 | 6 (15.7) | 5 (12.1) | 3 (13.0) | ||

| 3 | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (4.3) | ||

| Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer | 0.027 | ||||

| 1 | 3 (7.8) | 15 (36.5) | 3 (13.0) | 2.3 (1.65-3.2)2 | |

| 2 | 7 (18.4) | 6 (14.6) | 5 (21.7) | ||

| 3 | 26 (68.4) | 19 (46.3) | 15 (65.2) | ||

| Procedures | 0.16 | ||||

| 1 | 12 (31.5) | 4 (9.7) | 7 (30.4) | ||

| 2 | 12 (31.5) | 12 (29.2) | 8 (34.7) | ||

| 3 | 6 (15.7) | 11 (26.8) | 2 (8.6) | ||

| > 3 | 8 (20.9) | 14 (31.4) | 6 (26.0) | ||

| Number of procedures | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 2 | 0.07 | |

| Albumin at diagnosis | 36.37 ± 4.4 | 36.3 ± 4.7 | 36.0 ± 5.2 | 0.96 | 0.97 (0.84-1.11)1 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein at diagnosis | 944 ± 2162 | 337 ± 729 | 9232 ± 31376 | 0.05 | |

| International normalized ratio at diagnosis | 1.14 ± 0.23 | 1.19 ± 0.25 | 1.12 ± 0.18 | 0.46 | 11 |

| Bilirubin at diagnosis | 2.9 ± 7.8 | 1.02 ± 0.66 | 1.17 ± 0.56 | 0.19 |

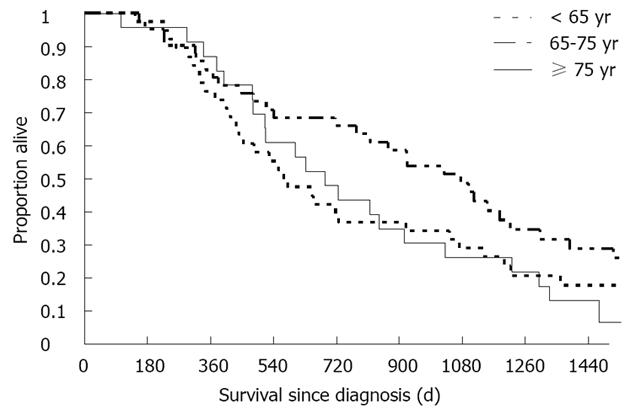

Survival analysis demonstrated similar survival patterns among the elderly patients and younger patients (Figure 1, P = 0.19). Overall, the cumulative follow-up time was 258 patient years. Median survival from diagnosis was 574 d (range: 143 d to 6 years), 1032 d (range: 154 d to 10 years) and 688 d (range: 104 d to 4.2 years) among patients in groups 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Respective survival rates at 1, 2 and 3 years from diagnosis were 74%, 37% and 31% among group 1 patients; 83%, 66% and 48% among group 2 patients; and 86%, 41% and 23% among group 3 patients. Multivariate survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazard regression model with variables of age (according to group), disease stage at diagnosis, number of TACE procedures, sex and AFP level at diagnosis found no significant difference in the mortality hazard of very elderly vs younger patients. The analysis was repeated with both the CLIP and Okuda staging systems, and the results were stable and consistent (Table 1).

Next, we assessed whether the number of TACE procedures was different among the groups. We hypothesized that elderly patients may have received different TACE regimens. The cohort patients described above underwent a total of 299 TACE procedures (Table 2). There were no differences between the age groups in pre-procedural care, including preventive treatment for contrast nephropathy and prophylactic antibiotics.

| < 65 yr | 65-75 yr | ≥75 yr | P value | |

| Number of procedures | 93 | 129 | 61 | |

| Preparation for contrast material exposure | 18 (19) | 38 (29) | 14 (22) | 0.37 |

| Iodine allergy and preparation | 1 (1) | 21 (16) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | 68 (73) | 95 (73) | 44 (72) | 0.7 |

| Cefamezine | 63 (67) | 87 (67) | 44 (71) | |

| Ceftazidime | 1 (1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Clindamycin | 2 (2) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Clindamycin and Ciprofloxacin | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Vancomycin | 2 (2) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Right upper quadrant abdominal pain | 16 (17) | 24 (18) | 5 (8) | 0.22 |

| Nausea | 9 (9.6) | 17 (13.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0.057 |

| Fatigue | 6 (6) | 6 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.36 |

| Fever | 21 (22) | 26 (2) | 5 (8) | 0.07 |

| Post-embolization syndrome | 23 (24) | 36 (27) | 10 (16) | 0.3 |

| Readmission | 3 (3.2) | 8 (6.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0.34 |

| Total length of stay | 3.6 (1.14) | 3.55 (1.1) | 3.3 (0.9) | 0.19 |

There were also no differences in post-procedural complications. There was a trend towards fewer post-embolization syndrome events among the elderly patients. Overall, there were 69 post-embolization syndrome events (23%). Some complications were very rare, including two cases of acute kidney injury (0.6%), two cases of sepsis (0.6%), two cases of hemorrhage (0.6%) and two cases of hemodynamic instability (0.6%). There was one event of vascular dissection and one event of pseudo-aneurysm.

There were 10 patients aged 80 years or older at diagnosis who were included in the analysis. Eight were women, two had BCLC stage I, three had BCLC stage II and five had BCLC stage III. Eight were HCV carriers. These patients underwent 34 procedures; there were five post-embolization events (15%) and one readmission within 30 d of the procedure. Nine patients survived one year; of these, three survived two years, while two survived three years.

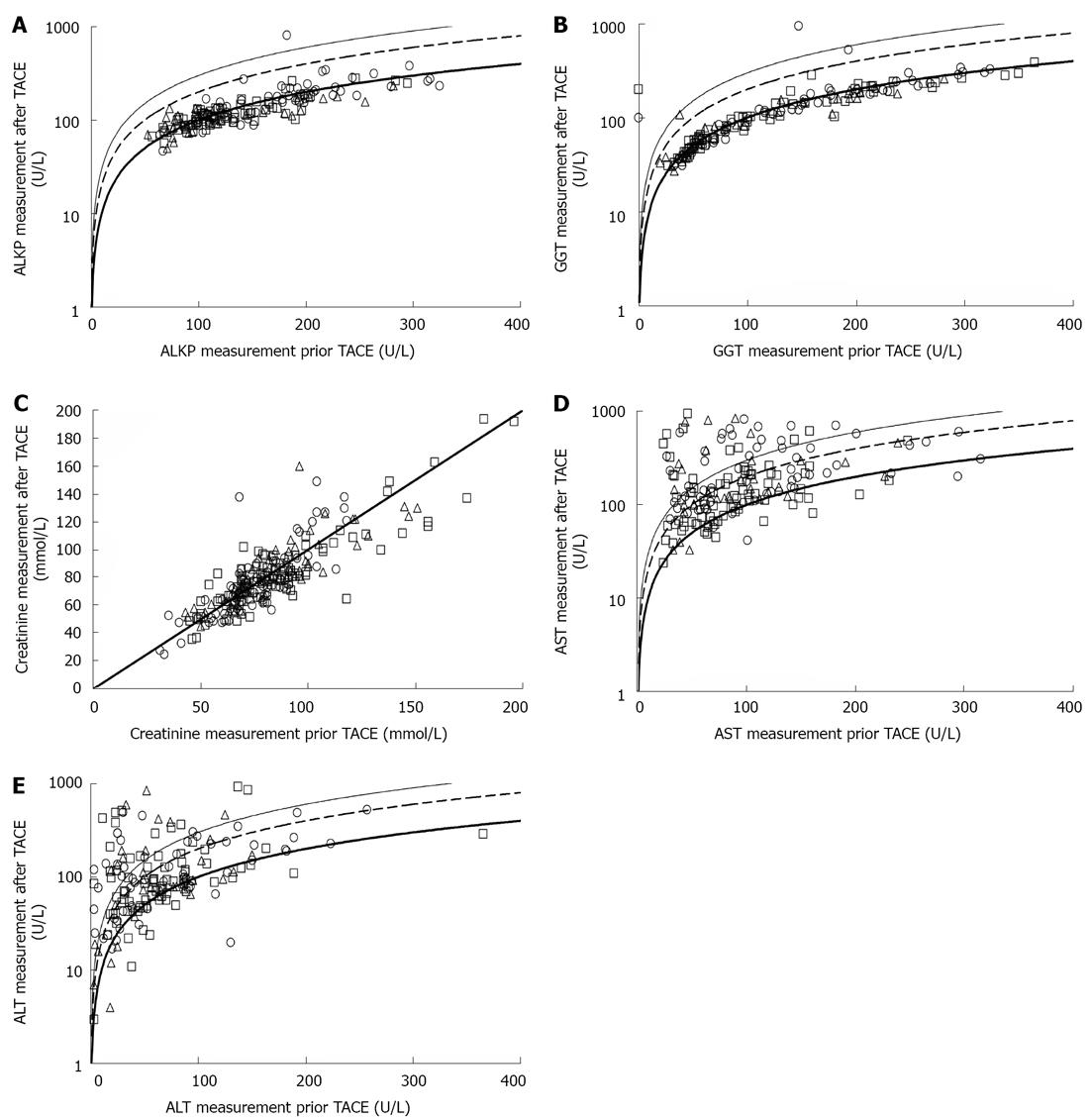

We hypothesized that older patients may be more prone to contrast-induced renal injury following TACE. Serum creatinine levels did not change after 55% (group 1), 58% (group 2) and 55% (group 3) of the procedures (P = 0.98). In 42% of all procedures, serum creatinine levels increased by no more than 25% above the baseline measurement taken prior to TACE. There were only two cases in which creatinine more than doubled (Figure 2). Increases in creatinine levels were not associated with increased mortality.

Both ALT and AST levels frequently rose following TACE. These increases were evenly distributed among age groups (P = 0.17 for ALT, and P = 0.69 for AST). ALT and AST levels were not increased after 25% and 17% of TACE procedures, respectively. In contrast, ALT and AST more than doubled in 40% and 43% of the procedures, respectively (Figure 2). GGT and ALKP did not increase following TACE procedures in any of the age groups (Figure 2). There was no association between post-TACE rise in hepatocellular enzymes and mortality.

In this study, we show that TACE is safe and effective in very elderly patients (≥ 75 years of age) who were diagnosed with HCC. Our results support previous findings which show that both survival and post-TACE complications do not differ between older and younger patients.

Current guidelines for the management of HCC do not stratify strategies according to age[11]. Still, the treating clinician may be concerned that TACE will be more hazardous for elderly patients, due to the perceived increased chance of renal or vascular complications, or the potential for liver function deterioration. Furthermore, given that elderly patients have a shorter life expectancy, the treating physician may assume that elderly patients might not survive long enough to benefit from any potential gains that the TACE confers on younger patients.

Previous studies used different cutoffs to define elderly. Some even defined elderly patients as those above 60 or 65 years[13-17]. In a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, published in 2002, increased age was not associated with decreased prognosis. However, mean patient age in the included studies ranged from 41 to 66 years of age. In most of the included trials, more than 50% of the participating patients had a Child-Pugh score below 7[7]. In these cohorts there was a significant misrepresentation of the older patients, far less than their proportion among patients with HCC, suggesting marked selection bias[18].

Reports of treatment outcomes in patients older than 70 years have shown inconsistent results with regard to prognosis, although most have shown that advanced age is not associated with worse prognosis. Poon et al[19] have shown that among patients older than 70 years, those offered resection and those offered TACE had comparable prognosis with treatment-matched younger controls. In a recent report describing the role of TACE among patients with HCC excluded from transplantation or surgical resection, the mean age of the patients was 70 years, survival was not stratified by age and was estimated at 91%, 86% and 80% at 1, 2 and 3 years, respectively[20]. A similar study, with 95 elderly patients (defined as above 70 years old, though most were younger than 75 years) demonstrated that after excluding patients referred for transplantation, age was not associated with poorer survival. Survival rates among patients above 70 years of age were 51%, 36% and 23% at 1, 2 and 3 years, respectively[21].

The Italian Liver Cancer group compared treatments for HCC over a twenty-year period. They included a comparison of elderly and younger patients who underwent TACE with an age cutoff of 70 years and a mean age in the elderly group of 74.9 years. They report no difference in prognosis between elderly and younger patients who underwent TACE[10]. Another study from China presented similar results[9].

Only a few studies have included a larger proportion of older patients. Dohmen et al[22] analyzed a cohort of 36 patients with HCC who were older than 80 years, and showed that disease stage rather than age was the major determinant of survival. The patients in the study received various interventions including TACE, chemotherapy and surgical resection. Two other studies showed that patients older than 75 years with HCC had a worse prognosis than younger patients, but attributed these findings to poorer treatment rather than age effect[23,24]. An analysis that focused on all treatment modalities in 40 patients older than 75 years compared to younger patients showed no difference in survival rates. In that study, 43% of the younger controls underwent liver transplantation. Among the elderly, TACE was the most frequent treatment modality[25]. In 2010, a study of patients who underwent TACE, which included 131 patients aged 70 to 79 years and 69 patients older than 80 years, showed that age was a predictor of increased mortality[26].

We found a 23% (69/299) post-embolization syndrome rate and a 2.4% (12/299) hospital readmission rate in patients undergoing TACE. Both complications were not increased in elderly patients. A recent review of adverse events associated with TACE reported the incidence of hepatic insufficiency as ranging between 1% and 50%, and that of cholecystitis was between 0% and 10%[16]. Post-embolization syndrome rates have been reported between 2% and 80%[6,8]. Previous assessment of acute kidney injury among patients undergoing TACE found no association between this adverse event and age[26].

Because our study was conducted in a "real-life" setting, it suffers from selection bias. This limitation is shared by all previously published studies. The strengths of our study are the prospective design, with complete patient follow-up, record analysis and data acquisition. We use a clear age cut-off of 75 years to define elderly patients. An important strength of our study is the systematic documentation of post-embolization complications, segregated to the age groups, and also the presentation of biochemistry result dynamics.

Given the body of literature and the natural history of non-curable HCC, our study provides data to support the use of TACE in selected, very elderly patients (older than 75 years old). These patients should be offered similar treatment regimens, including TACE and palliative care, as younger patients. TACE should not be withheld from elderly patients based on age criteria alone.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence is highest among patients over 70 years old. Though many are not candidates for curative therapy, they can benefit from life-prolonging interventions. Most existing literature provides information about younger patients. Trans-arterial chemo-embolization (TACE) has been shown to prolong survival among HCC patients, though there is little evidence of the procedure's safety and efficacy among very elderly HCC patients (above 75 years of age).

HCC is one of the most common neoplastic malignancies worldwide. Therapeutic options aiming for cure include liver transplantation, liver resection and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). TACE, sorafenib, palliative RFA and supportive care are palliative options, which in some cases also offer life prolongation. Current clinical research challenges include: (1) Innovative discovery of novel therapeutic modalities; (2) Improving the use of known treatment options by identifying patient characteristics which can predict better outcomes, which therapeutic option will maximize outcome and to broaden the population eligible to receive treatment. These challenges are met with an aging patient population, as the proportion of newly diagnosed elderly patients is consistently increasing.

In this study the authors included very elderly patients (older than 75 years), who have not been sufficiently represented in most published research so far. The authors compared survival time since diagnosis between the very elderly and younger patients. Additionally, the authors included critical information regarding TACE-associated complications and changes in common biochemistry tests. The authors show that the very elderly HCC patients enjoy the same survival benefits conferred by TACE on younger patients and that they do not experience more complications following this procedure.

There are several very practical implications which can be taken from this study: (1) TACE can be offered to patients above 75 years of age using the same clinical considerations which apply to younger patients; (2) Increases in hepatocellular enzymes alanine and aspartate aminotransferase are common and, by themselves, do not indicate poor or better response to treatment. In contrast, increases in the cholestatic enzymes gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase and in creatinine are not common and should warrant clinical investigation; (3) Post-embolization syndrome is common and has no prognostic implications.

HCC is a malignant disease of the liver, often presenting as a complication of long-standing liver disease and cirrhosis due to viral, alcoholic and metabolic etiologies. TACE is a minimally invasive procedure in which an artery (most often the femoral artery) is punctured; through it a catheter is introduced and advanced towards the blood vessels which provide arterial blood to the liver. After identifying which specific vessels provide blood supply to the liver tumor, toxic chemotherapy is injected in order to cause cancer cell death, and additionally, the arteries are blocked (embolized) in order to stop the blood supply to the tumor.

The study results are interesting and important with regard to epidemiological data. The theme is interesting and the study evaluations, as well as the statistical analysis, are well done. It is of great significance in providing evidence for clinicians to expand the age limit for TACE, and helps a lot for treatment decision making in elderly HCC patients.

P- Reviewers Cao GW, Roeb E, Yang SF S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25536] [Article Influence: 1824.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Reichman ME. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1485-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1196] [Cited by in RCA: 1325] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nordenstedt H, White DL, El-Serag HB. The changing pattern of epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42 Suppl 3:S206-S214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thuluvath PJ, Guidinger MK, Fung JJ, Johnson LB, Rayhill SC, Pelletier SJ. Liver transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1003-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wong H, Tang YF, Yao TJ, Chiu J, Leung R, Chan P, Cheung TT, Chan AC, Pang RW, Poon R. The outcomes and safety of single-agent sorafenib in the treatment of elderly patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Oncologist. 2011;16:1721-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oliveri RS, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Transarterial (chemo)embolisation for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD004787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cammà C, Schepis F, Orlando A, Albanese M, Shahied L, Trevisani F, Andreone P, Craxì A, Cottone M. Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2002;224:47-54. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Vogl TJ, Naguib NN, Nour-Eldin NE, Rao P, Emami AH, Zangos S, Nabil M, Abdelkader A. Review on transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma: palliative, combined, neoadjuvant, bridging, and symptomatic indications. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72:505-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yau T, Yao TJ, Chan P, Epstein RJ, Ng KK, Chok SH, Cheung TT, Fan ST, Poon RT. The outcomes of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization. Cancer. 2009;115:5507-5515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mirici-Cappa F, Gramenzi A, Santi V, Zambruni A, Di Micoli A, Frigerio M, Maraldi F, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, Benvegnù L. Treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients are as effective as in younger patients: a 20-year multicentre experience. Gut. 2010;59:387-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6567] [Article Influence: 469.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver, European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4517] [Article Influence: 347.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Biselli M, Forti P, Mucci F, Foschi FG, Marsigli L, Caputo F, Ravaglia G, Bernardi M, Stefanini GF. Chemoembolization versus chemotherapy in elderly patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and contrast uptake as prognostic factor. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M305-M309. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ikeda M, Okada S, Yamamoto S, Sato T, Ueno H, Okusaka T, Kuriyama H, Takayasu K, Furukawa H, Iwata R. Prognostic factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2002;32:455-460. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, Omata M, Okita K, Ichida T, Matsuyama Y, Nakanuma Y, Kojiro M, Makuuchi M. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 629] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee SH, Choi HC, Jeong SH, Lee KH, Chung JI, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Kim N, Lee DH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in older adults: clinical features, treatments, and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:241-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Olivo M, Valenza F, Buccellato A, Scala L, Virdone R, Sciarrino E, Di Piazza S, Marrone C, Orlando A, Fusco G. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: survival rate and prognostic factors. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:515-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | O’Suilleabhain CB, Poon RT, Yong JL, Ooi GC, Tso WK, Fan ST. Factors predictive of 5-year survival after transarterial chemoembolization for inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2003;90:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Ngan H, Ng IO, Wong J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: results of surgical and nonsurgical management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2460-2466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bargellini I, Sacco R, Bozzi E, Bertini M, Ginanni B, Romano A, Cicorelli A, Tumino E, Federici G, Cioni R. Transarterial chemoembolization in very early and early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients excluded from curative treatment: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1173-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kozyreva ON, Chi D, Clark JW, Wang H, Theall KP, Ryan DP, Zhu AX. A multicenter retrospective study on clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and outcome in elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncologist. 2011;16:310-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dohmen K, Shirahama M, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Optimal treatment strategy for elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:859-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pignata S, Gallo C, Daniele B, Elba S, Giorgio A, Capuano G, Adinolfi LE, De Sio I, Izzo F, Farinati F. Characteristics at presentation and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the elderly. A study of the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP). Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fernández-Ruiz M, Guerra-Vales JM, Llenas-García J, Colina-Ruizdelgado F. [Hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly: clinical characteristics, survival analysis, and prognostic indicators in a cohort of Spanish patients older than 75 years]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:625-631. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ozenne V, Bouattour M, Goutté N, Vullierme MP, Ripault MP, Castelnau C, Valla DC, Degos F, Farges O. Prospective evaluation of the management of hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:1001-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hsu CY, Huang YH, Su CW, Chiang JH, Lin HC, Lee PC, Lee FY, Huo TI, Lee SD. Transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and renal insufficiency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e171-e177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |