Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2514

Revised: January 10, 2013

Accepted: January 23, 2013

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 162 Days and 1.4 Hours

AIM: To investigate the outcome of patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) referred for endoscopy at 2 and 6 mo post endoscopy.

METHODS: Consecutive patients referred for upper endoscopy for assessment of GERD symptoms at two large metropolitan hospitals were invited to participate in a 6-mo non-interventional (observational) study. The two institutions are situated in geographically and socially disparate areas. Data collection was by self-completion of questionnaires including the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal disorders symptoms severity and from hospital records. Endoscopic finding using the Los-Angeles classification, symptom severity and it’s clinically relevant improvement as change of at least 25%, therapy and socio-demographic factors were assessed.

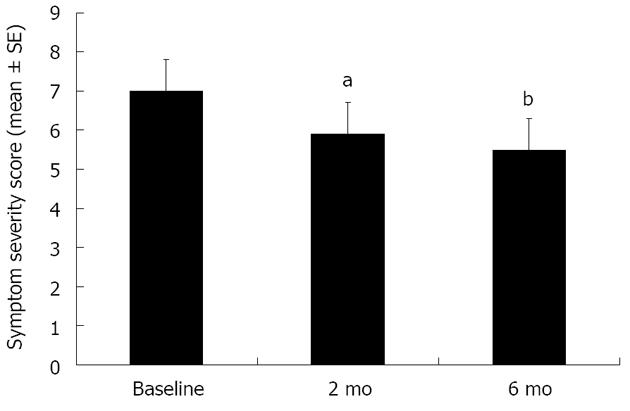

RESULTS: Baseline data were available for 266 patients and 2-mo and 6-mo follow-up data for 128 and 108 patients respectively. At baseline, 128 patients had erosive and 138 non-erosive reflux disease. Allmost all patient had proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy in the past. Overall, patients with non-erosive GERD at the index endoscopy had significantly more severe symptoms as compared to patients with erosive or even complicated GERD while there was no difference with regard to medication. After 2 and 6 mo there was a small, but statistically significant improvement in symptom severity (7.02 ± 5.5 vs 5.9 ± 5.4 and 5.5 ± 5.4 respectively); however, the majority of patients continued to have symptoms (i.e., after 6 mo 81% with GERD symptoms). Advantaged socioeconomic status as well as being unemployed was associated with greater improvement.

CONCLUSION: The majority of GORD patients receive PPI therapy before being referred for endoscopy even though many have symptoms that do not sufficiently respond to PPI therapy.

- Citation: Zschau NB, Andrews JM, Holloway RH, Schoeman MN, Lange K, Tam WC, Holtmann GJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease after diagnostic endoscopy in the clinical setting. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2514-2520

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2514

Heartburn and/or acid regurgitation occurring at least weekly, is very common in the general population[1]. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is defined as typical symptoms occurring 2 or more times weekly, or symptoms perceived as problematic to patients, or resulting in complications[2,3].

Many clinical trials have shown that proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are highly effective for healing of erosive GERD, and controlling symptoms[4]. Reflux symptoms are common, and treatment is readily available and regarded as highly efficacious. Thus, consistent with current guidelines many sufferers have therapy first, and are only referred for investigation (i.e., endoscopy) if treatment fails or symptoms relapse. PPI are currently the most effective therapy for GERD, although cost effectiveness[5], risks in long term treatment[6,7] and their role in endoscopy-negative reflux disease are open to discussion[8].

In the highly controlled clinical trial environment patients who do not respond to PPI therapy are typically excluded. Thus clinical trials may not mirror routine clinical care when patients are referred for endoscopy because symptoms are not controlled and clinicians might be left with an unrealistic expectation of treatment efficacy. Moreover, in routine clinical care settings, there are a number of confounders that may interfere with, or modulate, the response to therapy for reflux symptoms. While changes in lifestyle habits such as weight loss, smoking cessation and reduction of alcohol consumption are often advised[9] very little is known about the role of body mass index, alcohol and smoking or socioeconomic status (SES)[10] on the response to therapy in real life. Whilst lifestyle factors have been related to the risk of having reflux[1], it is unclear whether they affect the response to therapy. There are now sufficient data to show that less that 50% of patients with typical GERD symptoms have mucosal lesions. The remainder are referred to as patients with non erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (NERD). While some of these patients may have an increased acid exposure without mucosal lesions, other patients may not have an increase esophageal acid exposure and moreover, their heartburn symptoms might not be associated with episodes of esophageal acid exposure[11].

We therefore sought to determine and quantitate in a routine clinical setting in patients with GERD symptoms referred for endoscopy: (1) the symptom intensity and the improvement of symptoms to therapy (with PPIs); (2) the relation between symptoms and treatment response in relation to underlying structural lesions; and (3) whether lifestyle factors or socio-demographic variables affect this response in patients presenting for endoscopy because of reflux symptoms.

During a 24 mo period, patients referred, for endoscopic assessment of reflux symptoms at two large metropolitan hospitals were invited to participate in this observational study. The two institutions, the Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) and the Lyell McEwin Hospital (LMH) were both located in a single metropolitan Area Health Service (Central Northern Adelaide Health System, CNAHS), however they are located within geographically (approximately 25 km apart) and socially disparate areas[12]. The CNAHS serves a metropolitan and semi-rural population of more than 760000 residents. Both endoscopy units accept direct referrals from primary care doctors for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE). All endoscopists were board certified with more extensive experience in diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy. State of the art (Olympus) equipment was used.

This study did not include interventions other than obtaining informed consent und assessing symptoms and other parameters at baseline and during the follow-up. In particular there was no interference with normal care provided by general practitioners and specialists or interactions of the study staff that could shift attention towards symptoms or enhance compliance. Patients referred for UGIE with the primary complaints of typical reflux symptoms (heartburn +/- acid regurgitation) recorded as the indication on the referral for UGIE, between 18 and 65 years of age and capable of completing questionnaires were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria included significant medical co-morbidities (American Society of Anesthesiologists III or IV or reduced life expectancy), pregnancy and unstable psychiatric disorder and inability to read and write or communicate in English.

The study was designed as a prospective, observational study with no interference with routine clinical management. Patients were invited and consented on the day of UGIE and completed the survey at baseline and two and six mo after the initial assessment. Data collection was by self-completion of questionnaires and from hospital records. In order to avoid any interference with the study objectives, patients were only contacted once at the defined follow-up time points, no measures to increase compliance with medication or behavioural interventions outside routine clinical care were provided.

The study was approved by the human research ethics committees of both hospitals, and each patient gave informed consent. The study was registered at the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry as “Multivariate analysis of predictors for severity of mucosal lesions in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a clinical, epidemiological and endoscopic survey” (ACTRN12609000045213).

In addition to the questionnaires (see below), hospital records and UGIE reports were reviewed to collect relevant data. Endoscopic findings at baseline were recorded using the Los Angeles (LA) classification[13]. The SES of the patients was established according to patients’ residential postcodes using the Social Health Atlas of South Australia[12] and patients categorised into one of 3 groups: advantaged, average and disadvantaged.

The postal survey included the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal disorders symptom severity[14,15]. A symptom severity score (SSS) was calculated from it using 4 items covering reflux symptoms during the past week. The items used were: (1) heartburn (burning rising in your chest or throat) during the day; (2) regurgitation or reflux (fluid or liquid from your stomach coming up into your throat) during the day; (3) heartburn (burning rising in your chest or throat) at night (when recumbent); and (4) regurgitation or reflux (fluid or liquid from your stomach coming up into your throat) at night (when recumbent).

Severity of the symptoms was rated on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from “none” = 0 to “very severe” = 5, therefore the SSS could range from 0-20. This score was used as the outcome variable to assess patients’ reflux symptom severity over time. For this instrument we defined a clinically relevant improvement as change of at least 25% of symptom severity.

Means, standard deviations and percentages were calculated. t-tests or when appropriate non-parametric test were used to compare characteristics of patient groups. To assess which factors may affect symptom severity over time, bivariate correlations and non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney) were used between individual factors and the change in SSS from baseline to 2 and 6 mo. Variables which were significant in initial analyses, or thought to be biologically relevant, were then included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. SPSS 15 was used for all analyses (2006, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A sample size of > 100 subjects was considered sufficient to identify relevant effect at an alpha level of 0.05 and a beta > 0.75.

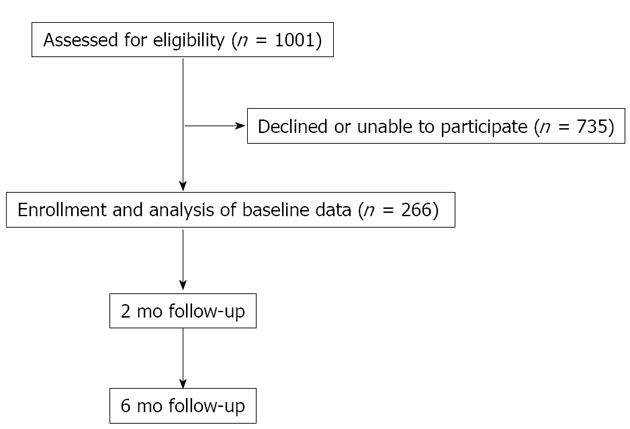

Across the 2 sites, 1001 patients were eligible to participate (598 at the RAH; 403 at the LHM), (52.2% female overall). In total, 266 participated, 173 from the RAH [response rate (RR) = 29%] and 93 from LMH (RR = 23%) (P = 0.35), 145 participants were female (54.5%). Patient flow and follow-up are shown in Figure 1.

Baseline demographic details are shown in Table 1. Of note, at baseline 63% of participants were on treatment with a PPI (while all patients had PPI for at least 4 wk in the past), almost one third were regular smokers and 15.6% had high alcohol intake (daily or greater than 5 standard drinks/d).

| LA-classification | NERD | Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | Grade D |

| n (F) | 138 (90) | 21 (13) | 33 (15) | 19 (5) | 55 (22) |

| (%, 95%CI) | (51.9, 45.9-57.8) | (7.9, 5.2-11.8) | (12.4, 9.0-16.0) | (7.1, 4.6-10.9) | (20.7, 16.2-25.9) |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD (range) | 49 ± 12.2 (19-65) | 42 ± 12.9 (19-62) | 50 ± 11.9 (22-65) | 46 ± 12.8 (29-65) | 53 ± 8.1 (37-65) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD (range) | 28.8 ± -6.4 (19-49) | 30 ± 8.5 (21-53) | 29.7 ± 6.1 (21-44) | 26.3 ± 5.5 (15-35) | 28.7± 7.6 (16-53) |

| Percentage BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 39.7% | 38.9% | 43.3% | 27.8% | 24.5% |

| PPI at enrolment | 61.5% | 50% | 71% | 57.9% | 70.4% |

| Tobacco | 25.2% | 30% | 8.7% | 21.4% | 7.9% |

| Alcohol (daily or > 50 g/d) | 7.7% | 13.3% | 23.8% | 14.3% | 34.2% |

| Employed | 54.4% | 66.7% | 55% | 50% | 44.7% |

| Married | 48.6% | 40% | 52.2% | 42.9% | 51.3% |

| Socioeconomically disadvantaged | 54.9% | 56.3% | 50% | 43.8% | 51.2% |

As shown in Table 2 participants from the community hospital were significantly older, more socioeconomically disadvantaged, had more NERD, included fewer Barrett’s surveillance cases, were more often smokers and had a trend for a greater proportion to be obese than those at the city hospital. However, there were no significant differences in gender mix or the proportion with high alcohol consumption between the hospitals.

| Variable | RAH-tertiary referral centre (n = 173) | LMH-community Hospital (n = 93) | P value |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD (range) | 48 ± 12.5 (19-65) | 51.5 ± 10.2 (23-65) | 0.027 |

| Disadvantaged SES | 56% | 74.4% | < 0.001 |

| LA-Grade NERD | 46.8% | 61.3% | 0.024 |

| LA-Grade C/D | 21.4% | 6.4% | 0.024 |

| Smoking | 14.7% | 31.3% | 0.007 |

| Alcohol (daily or > 5 Std. drinks/d) | 17.1% | 12.7% | 0.701 |

| Male gender | 48.6% | 60.2% | 0.171 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 32.1% | 44.1% | 0.064 |

Higher grades of esophagitis (LA grade C + D) were associated with male gender (M = 38.8% vs F = 18.6%, P < 0.001), older age (P = 0.014) and with heavy alcohol consumption (15/37 with heavy alcohol consumption vs 15/125 with nil or moderate alcohol consumption, P = 0.002). Interestingly, there was an inverse association between higher grades of esophagitis and current smoking (15.4% in smokers vs 29.9% in non-smokers, P = 0.017).

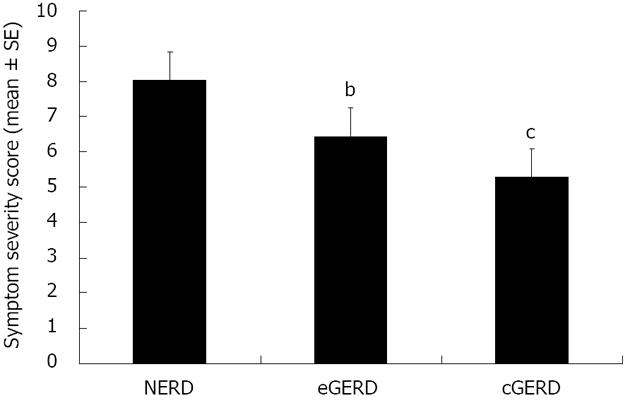

The cohort had a mean SSS of 7 (SD 5.5) out of a possible maximum of 20. Reflux symptoms were rated as moderate to severe by 22.1% of the patients. In patients with NERD, the symptom score was significantly higher than in those with erosive or complicated GERD (e.g., Barretts, Figure 2). Unemployed participants had a significantly higher mean symptom score at baseline than those who were employed (P = 0.007). Similarly, subjects with a lower SES had significantly more severe symptoms at baseline (8.1 ± 0.66) as compared to other patients (5.8 ± 0.52, P < 0.05); this difference was not explained by variation in the use of antisecretory drugs at baseline (P > 0.4) and overall there was no significant difference the in symptom score at baseline for patients with and without PPI therapy (without PPI 6.8 ± 0.75 vs with PPI 7.1 ± 0.47).

At 2 mo, 128 patients (48.1% of initial responders) agreed to be reassessed and 94 complete questionnaires were returned. At 6 mo, 108 participants (40.6% of initial responders) responded, providing 77 completed questionnaires.

Descriptive and univariate comparisons: During follow-up the vast majority of patients had PPI therapy. Only 9% never had PPI, and only 6% started PPI after the baseline visit. The overall mean symptom score significantly improved from baseline at two and six months (Figure 3). However, looking at individual improvements, only 15% of patients had improvement in their symptom score at 2 mo and 19% at 6 mo. The majority of subjects had residual reflux symptoms and 19% and 17% still rated their reflux symptoms as moderate to severe, at 2 and 6 mo respectively, compared to 22.1% at baseline. At 2 mo, a higher body mass index (BMI) correlated with a greater improvement in SSS (mean ± SD, 6.7 ± 28.8, P = 0.031). Only minor gender differences were noted; with a greater change of the absolute SSS from baseline to 2-mo seen in women compared to men (mean ± SD, 1.1 ± 4.3, P = 0.046), however there was no gender difference in symptom responsiveness at the 6-mo evaluation.

Multiple linear regressions: Multiple linear regression analyses were separately performed for the 2- and 6-mo time-points to identify factors were associated with changes in symptom severity over time. Factors included in the model were SES, BMI > 30 kg/m2, PPI use, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, marital and employment status. Neither model (2 or 6 mo) reached overall significance (P = 0.104, adjusted R2= 0.066 at 2 mo; P = 0.732, adjusted R2= -0.043 at 6 mo); indicating that the chosen set of socio-demographic and life style factors did not explain a significant proportion of the variability in change in symptom severity.

Amongst individual predictors; social status and employment status were each associated with significant improvement in symptoms score at 2 mo. Patients of advantaged social status had an average 3.3 points greater improvement in symptoms score than patients of average SES and 2.5 points gain on those of disadvantaged SES (P = 0.031 and 0.014 respectively). Unemployed patients had an average 2.2 points greater SSS improvement compared to those employed or studying (P = 0.02). No individual factors were significantly associated with change in symptom score from baseline to 6 mo.

The main findings of this study are: (1) In the routine clinical setting more than 90% of patients referred for the assessment of suspected GERD are or have been on treatment with a PPI by the time of endoscopy. Nevertheless slightly more than 50% (138/266) do not have any mucosal lesions; (2) Patients without mucosal lesions have significantly more severe symptoms as compared to patients with erosive or complicated GERD; and (3) There is statistically significant improvement of symptoms over 6 mo. However, while the available treatments (e.g., PPI) are considered highly effective for the healing of lesions and relief of symptoms, it is remarkable that the majority of patients continue to have GORD symptoms.

It is important to note that the majority of patients referred for endoscopic assessment of GERD symptoms, received PPI therapy at the time of endoscopy or had received PPI before. In spite of that 48% of patients were found to have mucosal lesions at the time of endoscopy. However, symptoms do not appear to be “driven by lesions” as symptom severity was significantly higher in patients without mucosal lesions as compared to those with lesions. Moreover, symptoms persisted in the majority of patients although there was a modest, even though statistically significant improvement of symptoms during follow-up.

Previous clinical trials have clearly shown that GERD patients can be effectively treated with PPI[16]. While there is no reason to question the data of these clinical trials, the typical patient now referred in the routine clinical setting for an endoscopy is already treated with PPI before an endoscopy is even considered. To our knowledge this is the first non-interventional prospective study that specifically examined this cohort of patients and aimed to define the response to therapy and possible influence of socio-demographic and lifestyle factors in a real world clinical setting. It is very striking that only a very small proportion of patients experience a substantial improvement of symptoms after endoscopy and being treated with a PPI.

Whilst medication adherence could not be verified in this observational study, it is possible that all patients have taken the medication at the appropriate time or at the individually prescribed dosage. However, it seems unlikely poor compliance is the major explanation for this apparent failure of PPI, as they give rapid symptom relief[17]. We therefore hypothesize that in this patient group excess oesophageal acidification is not likely to be the major driver for the symptoms. It is likely that some of the symptoms are manifestation(s) of functional gastrointestinal disorders. These are known to commonly co-exist in subjects with reflux[18], and would substantially account for the lack of response to PPI therapy. On the other side it is interesting that 9% of the group reported not being offered PPI therapy despite having the cardinal symptoms of reflux (heartburn/regurgitation).

The marginal improvement in symptoms over time (SSS 7 at baseline and 5.5 at 6 mo) shows that the usual care approach adopted falls short with regard to improvement of symptoms when compared with trial data[16]. Altogether, less than one quarter of patients improved over 6 mo and the percentage of patients with moderate to severe symptom severity only decreased from 22% to 19% after 2 mo and was still 17% at 6 mo. This may reflect the fact that now predominantly non-responders to PPI therapy are referred for endoscopy. Our data may raise the question if other diagnostic and therapeutic approaches might be needed for these patients. Our results showed at baseline that higher LA grades were more likely found in men, older subjects, and participants with higher alcohol consumption, consistent with several studies[1,19,20]. Interestingly, whilst these factors are associated with more severe baseline reflux symptoms, they did not modify the symptomatic response to therapy, again suggesting that symptoms in our cohort may not be entirely attributable to GERD. This is likely to be due to our patient selection process due to biases inherent in their referral, which appears to have resulted in a group with “reflux symptoms” not due to clear-cut GERD (high proportion referred with ongoing symptoms despite PPI therapy).

Tobacco smoking is a listed as a major risk factor for many diseases, but there are few studies in regard to reflux symptoms. Due to lowering the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter it is proposed as a possible risk factor for erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus[9,21]. Our data however, revealed greater tobacco use in patients with non-erosive or low grades esophagitis. This observation is based upon the post-hoc data analysis. Thus it needs to be independently confirmed before firm conclusions can be drawn with regard to this point. Of note, however, tobacco use did not influence the response to therapy over time in our cohort.

Whilst in the multivariable models, the set of socioeconomic and life style factors did not influence symptom severity over time, BMI > 30 kg/m2, SES and employment status, as individual factors, did influence symptom severity in our population. Patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 had greater improvement in SSS at both 2 and 6 mo, and advantaged social status and unemployment were both associated with a greater improvement in symptom severity over time. While this finding is based upon a post-hoc analysis and also requires independent prospective validation, it is reasonable to assume that a BMI > 30 kg/m2 increases reflux of acidic content into the esophagus. Thus inhibiting acid secretion would reduce esophageal acid exposure and improve symptoms.

Our study has the strength that it reflects the routine clinical setting. Patients were studied with minimal interference. Thus our “real-life” setting did not reflect the setting of clinical trials with regular contacts that facilitate compliance with medication. While all patients had be informed and consent obtained at baseline and symptoms assessed during the follow-up, there were no other interferences with routine care that potentially could affect the outcome. While this provides insights into the real world, this must be balanced against some limitations including a possible participation bias by including only those choosing to complete the questionnaires, and the appreciable dropout rate after 2 mo. However, consistent with most clinical trials a considerable proportion of patients declined to participate or could not participate for various reasons. However, characteristics of patients included into the study were not different from patients not included. Thus our finding and conclusions appear to be relevant for the whole population. These are also part of the strength of the study as this is far more representative of what happens in real world clinical medicine.

In summary, contrasting general beliefs, the majority of patients with reflux symptoms referred for endoscopy continue to have symptoms in spite of the use of highly potent PPI’s. Patients without endoscopic lesions appear to have more severe symptoms. The obvious persistence of symptoms suggests that there is the need to better monitor the response to therapy in these patients and to develop and properly use diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients with reflux symptoms who do not respond to the routine therapy with PPIs.

Authors aimed to study at 2 and 6 mo after endoscopy, the outcome of patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) referred for endoscopy under real life conditions. Little naturalistic data on reflux symptoms under usual care conditions exist. The majority of patients with GERD symptoms referred for endoscopy have already been or are currently treated with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). In this setting symptoms are more severe in patients without erosive lesions. After endoscopy with continued PPI therapy, there is a significant but modest improvement of symptoms however, the majority of patients continue to have symptoms. Thus long-term PPI therapy appears to be insufficient in providing relief of symptoms in a considerable proportion of patients. Patients unresponsive to PPI therapy for reflux symptoms may benefit from investigations other than upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. There is a need to develop and test new approaches for these patients.

Numerous trials suggest that in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease the currently available treatments (i.e., PPI) provide rapid control of symptoms and healing of lesions. Since these treatments are now widely available, they are frequently used prior to endoscopy and patients non-responsive to PPI are more likely to be referred for endoscopy. This study clearly demonstrates that there is a considerable unmet need with regard to symptom control in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

This is the first study that prospectively assessed the symptoms of GERD patients’ referred for endoscopy. The fact that the majority of patients continued to have symptoms contrasts general beliefs. Endoscopy alone might not be appropriate to target therapy in patients with GERD symptoms.

This research has considerable implications in the clinical setting. While highly potent treatments (e.g., PPI) are widely available and used, patients referred for endoscopy are more likely to have symptoms that do not respond to PPI. Thus the study suggests that other treatment modalities might be required.

In this manuscript, the authors investigated the outcome of patients with symptoms of GERD referred for endoscopy at 2 and 6 mo post endoscopy. The study was uniquely performed and the results were well discussed with no serious methodological issues.

P- Reviewers Van Rensburg C, Shimatan T S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1392-1413. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bardhan KD. Duodenal ulcer and gastroesophageal reflux disease today: long-term therapy--a sideways glance. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:211-224. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Overutilization of proton pump inhibitors: a review of cost-effectiveness and risk [corrected]. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 2:S27-S32. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Insogna KL. The effect of proton pump-inhibiting drugs on mineral metabolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104 Suppl 2:S2-S4. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, Kreiner G, Christ G, Jilma B. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am Heart J. 2009;157:148.e1-148.e5. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Modlin IM, Hunt RH, Malfertheiner P, Moayyedi P, Quigley EM, Tytgat GN, Tack J, Holtmann G, Moss SF. Non-erosive reflux disease--defining the entity and delineating the management. Digestion. 2008;78 Suppl 1:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Zheng Z, Nordenstedt H, Pedersen NL, Lagergren J, Ye W. Lifestyle factors and risk for symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in monozygotic twins. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:87-95. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Turrell G, Mathers CD. Socioeconomic status and health in Australia. Med J Aust. 2000;172:434-438. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Armstrong D. A critical assessment of the current status of non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion. 2008;78 Suppl 1:46-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Glover J, Glover L, Tennant S, Page A. A Social Health Atlas of South Australia. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide 2006; . |

| 13. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Rentz AM, Kahrilas P, Stanghellini V, Tack J, Talley NJ, de la Loge C, Trudeau E, Dubois D, Revicki DA. Development and psychometric evaluation of the patient assessment of upper gastrointestinal symptom severity index (PAGI-SYM) in patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:1737-1749. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Revicki DA, Rentz AM, Tack J, Stanghellini V, Talley NJ, Kahrilas P, De La Loge C, Trudeau E, Dubois D. Responsiveness and interpretation of a symptom severity index specific to upper gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:769-777. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Haag S, Holtmann G. Onset of relief of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: post hoc analysis of two previously published studies comparing pantoprazole 20 mg once daily with nizatidine or ranitidine 150 mg twice daily. Clin Ther. 2010;32:678-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zheng RN. Comparative study of omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and esomeprazole for symptom relief in patients with reflux esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:990-995. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kaji M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Kohata Y, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, Watanabe K, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Arakawa T. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1151-1156. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Fock KM, Talley NJ, Fass R, Goh KL, Katelaris P, Hunt R, Hongo M, Ang TL, Holtmann G, Nandurkar S. Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:8-22. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chen M, Xiong L, Chen H, Xu A, He L, Hu P. Prevalence, risk factors and impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a population-based study in South China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:759-767. [PubMed] |