Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2501

Revised: November 13, 2012

Accepted: November 14, 2012

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 23 Days and 16.9 Hours

AIM: To address endoscopic outcomes of post-Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) patients diagnosed with a “redundant bile duct” (RBD).

METHODS: Medical records of patients who underwent OLT at the Liver Transplant Center, University Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Texas were retrospectively analyzed. Patients with suspected biliary tract complications (BTC) underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). All ERCP were performed by experienced biliary endoscopist. RBD was defined as a looped, sigmoid-shaped bile duct on cholangiogram with associated cholestatic liver biomarkers. Patients with biliary T-tube placement, biliary anastomotic strictures, bile leaks, bile-duct stones-sludge and suspected sphincter of oddi dysfunction were excluded. Therapy included single or multiple biliary stents with or without sphincterotomy. The incidence of RBD, the number of ERCP corrective sessions, and the type of endoscopic interventions were recorded. Successful response to endoscopic therapy was defined as resolution of RBD with normalization of associated cholestasis. Laboratory data and pertinent radiographic imaging noted included the pre-ERCP period and a follow up period of 6-12 mo after the last ERCP intervention.

RESULTS: One thousand two hundred and eighty-two patient records who received OLT from 1992 through 2011 were reviewed. Two hundred and twenty-four patients underwent ERCP for suspected BTC. RBD was reported in each of the initial cholangiograms. Twenty-one out of 1282 (1.6%) were identified as having RBD. There were 12 men and 9 women, average age of 59.6 years. Primary indication for ERCP was cholestatic pattern of liver associated biomarkers. Nineteen out of 21 patients underwent endoscopic therapy and 2/21 required immediate surgical intervention. In the endoscopically managed group: 65 ERCP procedures were performed with an average of 3.4 per patient and 1.1 stent per session. Fifteen out of 19 (78.9%) patients were successfully managed with biliary stenting. All stents were plastic. Selection of stent size and length were based upon endoscopist preference. Stent size ranged from 7 to 11.5 Fr (average stent size 10 Fr); Stent length ranged from 6 to 15 cm (average length 9 cm). Concurrent biliary sphincterotomy was performed in 10/19 patients. Single ERCP session was sufficient in 6/15 (40.0%) patients, whereas 4/15 (26.7%) patients needed two ERCP sessions and 5/15 (33.3%) patients required more than two (average of 5.4 ERCP procedures). Single biliary stent was sufficient in 5 patients; the remaining patients required an average of 4.9 stents. Four out of 19 (21.1%) patients failed endotherapy (lack of resolution of RBD and recurrent cholestasis in the absence of biliary stent) and required either choledocojejunostomy (2/4) or percutaneous biliary drainage (2/4). Endoscopic complications included: 2/65 (3%) post-ERCP pancreatitis and 2/10 (20%) non-complicated post-sphincterotomy bleeding. No endoscopic related mortality was found. The medical records of the 15 successful endoscopically managed patients were reviewed for a period of one year after removal of all biliary stents. Eleven patients had continued resolution of cholestatic biomarkers (73%). One patient had recurrent hepatitis C, 2 patients suffered septic shock which was not associated with ERCP and 1 patient was transferred care to an outside provider and records were not available for our review.

CONCLUSION: Although surgical biliary reconstruction techniques have improved, RBD represents a post-OLT complication. This entity is rare however, endoscopic management of RBD represents a reasonable initial approach.

- Citation: Torres V, Martinez N, Lee G, Almeda J, Gross G, Patel S, Rosenkranz L. How do we manage post-OLT redundant bile duct? World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2501-2506

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2501.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2501

Despite the dramatic improvements in surgical techniques, biliary tract complications (BTC) are still a significant source of morbidity and mortality after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)[1,2]. Since the beginning of liver transplantation, the biliary reconstruction has been a sensitive area regarding graft and recipient complications.

Presently, clinical evidence supports the choledo-choledocojejunostomy over the T-tube stent placement or Roux-en-Y choledocho-jejunostomy, as the preferred method of biliary reconstruction[3,4]. It is postulated that several factors (e.g., donor and recipient biliary ductal anatomy, duct-duct anastomosis technique, and blood supply to the bile ducts) can affect the final post-surgical bile duct configuration and may result in its ultimate successful function[5,6]. Surgical management used to represent the initial standard of care for BTC; however, the advancement in endoscopic therapeutic interventions has replaced prompt surgical intervention in most of the immediate and delayed complications[7-12].

Endoscopic therapy has been successful in the management of BTC. During the performance of the endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), interventions such as: endoprosthesis (biliary stent) placement with or without concurrent sphincterotomy, balloon dilatation of anastomotic strictures, can be included[12].

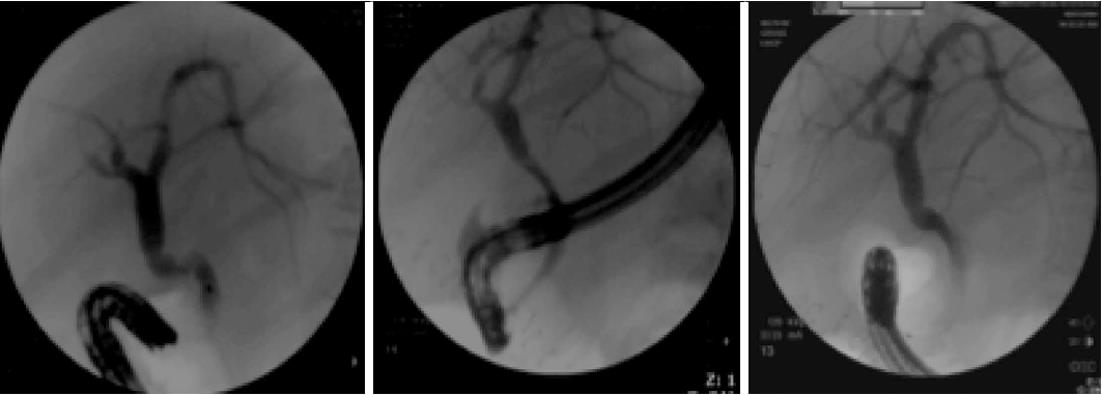

Bile duct stones, bile leaks and anastomotic strictures are among the most common post-transplant complications reported[13-19]. The reported incidence of such complications among different centers has been variable[8,12,17]. Our institution has previously reported the endoscopic experience with BTC in the post-OLT patient, however data did not include management of a “redundant bile duct” (RBD) (Figure 1)[8].

We define the “RBD” a surgically reconstructed donor-recipient extrahepatic bile duct, which due to its length (longer than the native recipient duct), in the absence of anastomotic stricture, creates a looped, sigmoid-shaped (“S”, “Z”) appearance, which leads to delayed bile flow into the duodenum, functionally translating into cholestasis and abnormal pattern of the liver associated tests.

The term was described as an analogy to the “redundant colon”, which describes a large intestine (colon) that is longer than normal and as a result has repetitive, overlapping loops. Typically, the “redundant colon” is a normal anatomic variation.

From our large transplanted data we present our endoscopic experience with the RBD treatment in the post-OLT patient. To our best knowledge, this is the first presentation of successful endoscopic management of the RBD in the post-OLT patient.

We performed a retrospective analysis of records from the Transplant Clinic, Endoscopy and radiology of patients who underwent OLT at the Liver Transplant Center, University Health Science Center at San Antonio.

One thousand two hundred and eighty-two patient records who received OLT from 1992 through 2011 were reviewed. Patients with biliary T-tube placement, biliary anastomotic strictures, bile leaks, bile-duct stones-sludge and suspected sphincter of oddi dysfunction were excluded.

Patients who underwent ERCP in the post-transplant period, indication and number of procedures per patient were reviewed. Laboratory data and pertinent radiographic imaging noted included the pre-ERCP period and a follow-up period of 6-12 mo after the last ERCP intervention.

RBD was identified as a sigmoid-shaped bile duct on cholangiogram (Figure 1) with associated cholestatic liver biomarkers. Endoscopic intervention included biliary stent placement with or without sphincterotomy. All ERCP were performed by experienced biliary endoscopists.

The incidence of RBD, the number of ERCP corrective sessions, and the type of endoscopic interventions were recorded. Successful response to endoscopic therapy (resolution of RBD) was defined as normalization of cholestatic liver profile up to one year after last endoscopic intervention and resolution of cholangiographic abnormalities (Figure 2).

Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS statistical software (version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC). We used the χ2 test to test whether categorical variables differed between individuals whose RBD resolved with ERCP and counterparts that failed ERCP intervention. Comparisons between the 2 groups for continuous variables were performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test (a nonparametric test). Results are reported as median and range or percentage as appropriate. Significance was assumed for P < 0.05 (2 sided).

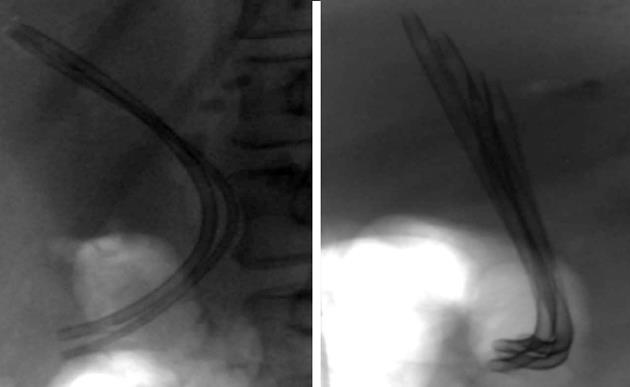

Two hundred and twenty-four patients underwent ERCP for suspected BTC. RBD was reported in each of the initial cholangiograms by three individual experienced endoscopist (Patel S, Gross G, Rosenkranz L) and reviewed by the authors of the manuscript. Twenty-one out of 1282 (1.6%) of liver transplanted patients were identified as having RBD. Patient demographics are listed in Table 1. There were 12 men and 9 women, average age of 59.6 years. Primary indication for liver transplantation was end stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis C (71.4%). Primary indication for ERCP was cholestatic pattern of liver associated biochemical markers. Nineteen out of 21 patients underwent endoscopic therapy and 2/21 required immediate surgical intervention, for failure to stenting the bile duct. In the endoscopically managed group: 65 ERCP procedures were performed with an average of 3.4 per patient and 1.1 stent per session. Fifteen out of 19 (78.9%) patients were successfully managed with biliary stenting. Interventions and results are listed in Table 2. All stents were plastic. Selection of stent size and length were based upon endoscopist preference. Stent size ranged from 7 to 11.5 Fr (average stent size 10 Fr); Stent length ranged from 6 to 15 cm (average length 9 cm). Each stent remained in place for an average of 93 d. Concurrent biliary sphincterotomy was performed in 10/19 patients. Single ERCP session was sufficient in 6/15 (40.0%) patients, whereas 4/15 (26.7%) patients needed two ERCP sessions and 5/15 (33.3%) patients required more than two (average of 5.4 ERCP procedures). Single biliary stent was sufficient in 5 patients; the remaining patients required an average of 4.9 stents. Figure 3 represents a cholangiogram with multiple stents placed in a redundant bile duct. Four out of 19 (21.1%) patients failed endotherapy (lack of resolution of RBD and recurrent cholestasis in the absence of biliary stent) and required either choledocojejunostomy (2/4) or percutaneous biliary drainage (2/4). The medical records of the 15 successful endoscopically managed patients were reviewed for a period of one year after removal of all biliary stents. Eleven patients had continued resolution of cholestatic biomarkers (73%). One patient had recurrent hepatitis C, 2 patients suffered septic shock which was not associated with ERCP and 1 patient was transferred care to an outside provider and records were not available for our review. Endoscopic complications (ERCP-related) recorded included: 2/65 (3%) post-ERCP pancreatitis and 2/10 (20%) non-complicated post-sphincterotomy bleeding. No endoscopic related mortality was found.

| Men | 12 |

| Women | 9 |

| Average age (yr) | 59.6 |

| Indication for OLT | |

| Hepatitis C | 15 |

| Cryptogenic | 2 |

| Steatohepatitis | 1 |

| Medication induced failure | 1 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 1 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 |

| Average time (d) from OLT to ERCP | 88.1 |

| Indication for ERCP | |

| Cholestatic LFT | 21/21 |

| Results | Resolved (n = 15) | Failure (n = 6) | P value |

| Men n (%) | 8/15 (53.3) | 4/6 (66.7) | 0.577 |

| Age1, yr | 59.0 (39.0-70.0) | 64.5 (50-75) | 0.094 |

| Hepatitis C indication n (%) | 11/15 (73.3) | 4/6 (66.7) | 0.760 |

| Time from OLT to ERCP1, d | 14 (4-1059) | 225 (8-865) | 0.086 |

| Total ERCP | 3 (2-10) | 3 (1-4) | 0.492 |

| Total biliary stents placed | |||

| Average stent per patient1 | 3 (0-15) | 2 (0-4) | 0.475 |

| Average stent per session1 | 1.0 (0-1.5) | 0.9 (0-1) | 0.602 |

| ERCP sessions for resolution | - | ||

| Single session | 6/15 | - | |

| Two sessions | 4/15 | - | |

| > Two sessions | 5/15 | - | |

| Percutaneous biliary drainage | 2 | - | |

| Choldocojejunostomy | 2 | - | |

| T bili1, mg/dL | 5.0 (0.3-37.3) | 6.1 (1.2-34.9) | 0.586 |

| AST1 | 122 (34-444) | 190 (40-1131) | 0.392 |

| ALT1 | 248 (42-668) | 262 (58-1579) | 0.846 |

| Alk phos1 | 460 (109-1066) | 345 (243-936) | 0.907 |

Since their initial description, BTC remain a significant source of morbidity and mortality after OLT. Complication rates have been reported as s high as 20% in some series[18]. During organ procurement, the surgeon attempts to minimize any disruption of the donor bile duct blood supply using a variety of techniques[20-24]. During transplantion, surgeons approximate the donor liver and bile duct to the native bile duct stump with caution. A laparotomy pad is placed above the liver, in order to maintain proper positioning during anastomosis and once completed, the pad is removed and the liver allowed to retract cephalad into its natural position. The bile duct is anastomosed with a gentle tension in order to reduce the risk of ischemia and bile leaks. Additionally, torsion of the liver during the transplant may lead to tension and leaks. It should be known that the surgeons do not make special attempts to avoid redundancy. Clearly overt discrepancies are addressed, but this aspect of the operation is quick and concise.

These techniques are performed to preserve blood supply and may theoretically lead to less ischemic bile duct complications. The successful endoscopic management of biliary leaks, bile duct strictures and sphincter dysfunction has previously been reported however, to our best knowledge, this is the first report of successful endoscopic management of a RBD in the post-OLT patient. Although post-OLT RBD represents an uncommon complication with an incidence of 1.6%, endoscopic management appears to be a reasonable initial approach as 78.9% of patients with a RBD post-OLT can be successfully managed with a combination of biliary stenting and sphincterotomy. Endoprosthesis selection is based on the endoscopist preference and comprises plastic biliary stents of variable width (7-11.5 Fr) and length, therefore it is difficult to comment in a non-randomized retrospective study if stent size or length impacted the overall outcome. The exact mechanism of resolution remains unclear, however, we suspect that stent placement alters the configuration of duct anatomy thereby leading to a resolution of the redundant duct. Hepatobiliary biopsies pre and post stent placement would aid in the further evaluation of the histochemical changes associated with this entity[25,26]. However this was not the main endpoint but does represent an avenue of further research. One year follow up of bilirubin and liver associated enzymes also suggest that endoscopic treatment is a viable option as 73% had continued resolution of cholestatic of liver profile.

Since their initial description, biliary tract complications (BTC) remain a significant source of morbidity and mortality after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT). Despite improvement in surgical techniques, the biliary reconstruction remains a sensitive area regarding graft and recipient complications. Endoscopic therapies have been effective in the management of BTC. Authors present their experience with “redundant bile duct” (RBD) in the post-OLT setting.

Management of BTC in the post-OLT setting has previously been reported; however, endotherapy and outcomes in the management of the RBD has not been described until present. The surgical management of the RBD has been published. Authors’ group is the first to propose endoscopic management via a combination of biliary stenting and sphincterotomy as an initial approach to the RBD.

This is the first to demonstrate that a RBD can be successfully managed with a combination of biliary stenting and sphincterotomy with a 78.9% success rate at our institution. One year follow up data also suggests that endoscopic management confers a sustained response.

Although post-OLT RBD an uncommon complication, endoscopic management appears to be a reasonable initial approach.

BTC include: leaks, strictures, retained stones and sphincter of oddi dysfunction. RBD is a surgically reconstructed donor-recipient extrahepatic bile duct which creates a looped, sigmoid-shaped (“S”, “Z”) appearance thereby resulting in delayed bile flow into the duodenum, OLT, Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography.

This manuscript reports on an unusual problem which they have termed the RBD. They reference their own prior study which suggests that such an entity may not be widely known or even accepted. Given that this could represent a real entity, publication may be appropriate.

P- Reviewers Wilcox CM, Garcia-Cano J S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Greif F, Bronsther OL, Van Thiel DH, Casavilla A, Iwatsuki S, Tzakis A, Todo S, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. The incidence, timing, and management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1994;219:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wojcicki M, Milkiewicz P, Silva M. Biliary tract complications after liver transplantation: a review. Dig Surg. 2008;25:245-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Neuhaus P, Platz KP. Liver transplantation: newer surgical approaches. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;8:481-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Krom RA, Kingma LM, Haagsma EB, Wesenhagen H, Slooff MJ, Gips CH. Choledochocholedochostomy, a relatively safe procedure in orthotopic liver transplantation. Surgery. 1985;97:552-556. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rabkin JM, Orloff SL, Reed MH, Wheeler LJ, Corless CL, Benner KG, Flora KD, Rosen HR, Olyaei AJ. Biliary tract complications of side-to-side without T tube versus end-to-end with or without T tube choledochocholedochostomy in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1998;65:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Neuhaus P, Brölsch C, Ringe B, Lauchart W, Pichlmayr R. Results of biliary reconstruction after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1984;16:1225-1227. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Todo S, Furukawa H, Kamiyama T. How to prevent and manage biliary complications in living donor liver transplantation? J Hepatol. 2005;43:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Torres VJ, Gross G, Patel S. Endoscopic management of biliary tract complications in the liver transplant patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB159. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Pfau PR, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Long WB, Lucey MR, Olthoff K, Shaked A, Ginsberg GG. Endoscopic management of postoperative biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:55-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tsujino T, Isayama H, Sugawara Y, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, Yamashiki N, Tada M. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2230-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stratta RJ, Wood RP, Langnas AN, Hollins RR, Bruder KJ, Donovan JP, Burnett DA, Lieberman RP, Lund GB, Pillen TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Surgery. 1989;106:675-683; 683-684. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sanna C, Giordanino C, Giono I, Barletti C, Ferrari A, Recchia S, Reggio D, Repici A, Ricchiuti A, Salizzoni M. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with post-liver transplant biliary complications: results of a cohort study with long-term follow-up. Gut Liver. 2011;5:328-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Malago M, Broelsch CE, Treichel U, Gerken G. Balloon dilatation vs. balloon dilatation plus bile duct endoprostheses for treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Testa G, Malagò M, Broelseh CE. Complications of biliary tract in liver transplantation. World J Surg. 2001;25:1296-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Egawa H, Inomata Y, Uemoto S, Asonuma K, Kiuchi T, Fujita S, Hayashi M, Matamoros MA, Itou K, Tanaka K. Biliary anastomotic complications in 400 living related liver transplantations. World J Surg. 2001;25:1300-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Duailibi DF, Ribeiro MA. Biliary complications following deceased and living donor liver transplantation: a review. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:517-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ostroff JW. Post-transplant biliary problems. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:163-183. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, Kalayci C, Lumeng L, Chalasani N, Kwo P, Lehman GA. Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with choledochocholedochostomy anastomosis: endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:224-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tanaka K, Uemoto S, Tokunaga Y, Fujita S, Sano K, Nishizawa T, Sawada H, Shirahase I, Kim HJ, Yamaoka Y. Surgical techniques and innovations in living related liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1993;217:82-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 471] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Sano K, Ohkubo T, Kaneko J, Takayama T. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in living-related liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1348-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Lin TS, Concejero AM, Chen CL, Chiang YC, Wang CC, Wang SH, Liu YW, Yang CH, Yong CC, Jawan B. Routine microsurgical biliary reconstruction decreases early anastomotic complications in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1766-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Buis CI, Hoekstra H, Verdonk RC, Porte RJ. Causes and consequences of ischemic-type biliary lesions after liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:517-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sanchez-Urdazpal L, Gores GJ, Ward EM, Maus TP, Buckel EG, Steers JL, Wiesner RH, Krom RA. Diagnostic features and clinical outcome of ischemic-type biliary complications after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1993;17:605-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu YY, Ji J, Zhou GW, Shen BY, Chen H, Yan JQ, Peng CH, Li HW. Liver biopsy in evaluation of complications following liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1678-1681. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Adeyi O, Fischer SE, Guindi M. Liver allograft pathology: approach to interpretation of needle biopsies with clinicopathological correlation. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:47-74. [PubMed] |