Published online Apr 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2445

Revised: March 18, 2013

Accepted: March 21, 2013

Published online: April 28, 2013

Processing time: 224 Days and 17.3 Hours

During the course of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), surgery may be needed. Approximately 20% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) will require surgery, whereas up to 80% of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients will undergo an operation during their lifetime. For UC patients requiring surgery, total proctocolectomy and ileoanal pouch anastomosis (IPAA) is the operation of choice as it provides a permanent cure and good quality of life. Nevertheless a permanent stoma is a good option in selected patients, especially the elderly. Minimally invasive surgery has replaced the conventional open approach in many specialized centres worldwide. Laparoscopic colectomy and restorative IPAA is rapidly becoming the standard of care in the treatment of UC requiring surgery, whilst laparoscopic ileo-cecal resection is already the new gold standard in the treatment of complicated CD of terminal ileum. Short term advantages of laparoscopic surgery includes faster recovery time and reduced requirement for analgesics. It is, however, in the long term that minimally invasive surgery has demonstrated its superiority over the open approach. A better cosmesis, a reduced number of incisional hernias and fewer adhesions are the long term advantages of laparoscopy in IBD surgery. A reduction in abdominal adhesions is of great benefit when a second operation is needed in CD and this influences positively the pregnancy rate in young women undergoing restorative IPAA. In developing the therapeutic plan for IBD patients it should be recognized that the surgical approach to the abdomen has changed and that surgical treatment of complicated IBD can be safely performed with a true minimally invasive approach with great patient satisfaction.

Core tip: The clinical management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients has dramatically changed in the last decades and primary, secondary and even tertiary levels of medical treatment are available to treat both Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. However, it should be recognized that surgical approaches have also changed, for the better, in the last few years and that minimally invasive surgery is now available in most centers. The timing of surgery is a key issue for proper management of IBD patients. Laparoscopic surgery should be seen as less aggressive than the standard surgical approach and could lower the threshold for surgical intervention.

- Citation: Sica GS, Biancone L. Surgery for inflammatory bowel disease in the era of laparoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(16): 2445-2448

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i16/2445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2445

During the course of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), surgery may be needed. Approximately 20% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) will require surgery, whereas up to 80% of Crohn’s disease (CD) patients will undergo an operation during their lifetime[1]. For UC patients requiring surgery, total proctocolectomy is the operation of choice as it provides a permanent cure and ileoanal pouch anastomosis (IPAA) has replaced the classic permanent ileostomy as the procedure of choice to accompany a proctocolectomy. Partial colectomy is rarely performed because of the high probability that the disease will recur in the remaining colon. Nevertheless partial colectomy and ileo-rectal anastomosis as well as proctocolectomy and permanent ileostomy are still good options in selected patients, especially the elderly.

For CD, surgery is not a definitive cure. Therefore, intestinal resection is indicated for patients who are refractory to the therapy or who are intolerant to medical treatments. In addition, patients that show severe complications of the disease will require surgery for obstruction, recurrent sub-obstructions, abdominal abscesses, perforation, massive bleeding or even cancer. The most common surgical procedure is ileo-cecal resection and primary reconstruction, which is indicated in patients with CD of distal ileum and/or ileo-colon. Stricturoplasty is less frequently indicated in patients with limited proximal small bowel strictures. Endoscopic dilatations of jejunum and ileum and more limited resections are also employed in a minority of cases. Endoscopic recurrence 1 year after ileo-colonic resection is observed in up to 80% of patients, while clinical recurrence is observed in about 20% of patients at 2 years and in up to 80% at 20 years[2].

There is little question that the timing of surgical intervention is a key issue for proper management of IBD patients. Indication and timing of surgery in IBD requires a joint evaluation by dedicated gastroenterologists and surgeons.

IBD surgery can be regarded as a cure for UC whilst it is undertaken to improve symptoms and to ameliorate the quality of life for CD patients. In both UC and CD, surgery can be a salvage procedure for acute, severe disease.

Although gastroenterologists are familiar with the potential complications associated with acute severe disease, most are reassured by statistics consistently showing an overall standardized mortality ratio for IBD patients near to that of general population[3]. A large scale analysis performed in the Oxford region (United Kingdom) using record linkage studies, showed that 3-year mortality was significantly lower among people who underwent elective colectomy for IBD than among those who were admitted to hospital without colectomy or who had had emergency colectomy[4]. The most worrying finding of the study by Roberts and colleagues is that in patients admitted for UC and CD who had no surgery (13.6% and 10.1% respectively) most deaths occur between 6 mo and 36 mo after admission. The decision to operate is an important one and should be made after a careful evaluation of all the clinical variables in each individual patient at the time of the diagnosis of the disease. Undoubtedly, many people suffer needlessly because they try to avoid surgery. Surgical delay does not only put the patient through unnecessary periods of pain and suffering, but it can also increase the risks of operative complications and ultimately lead to a worse outcome. On the other hand, it is clear that avoiding or delaying surgery may be the better choice for IBD patients, particularly in young CD patients, because of the almost certain recurrence of the lesions.

The general belief that surgery for IBD should be the last resort is flawed by reports on outcomes after colectomy in IBD patients, showing a relatively good prognosis[2,5-7]. However, these reports are mainly small, short term studies from specialist centers, not taking into account data from district hospitals where operations are performed mainly in emergency situations or with less positive results.

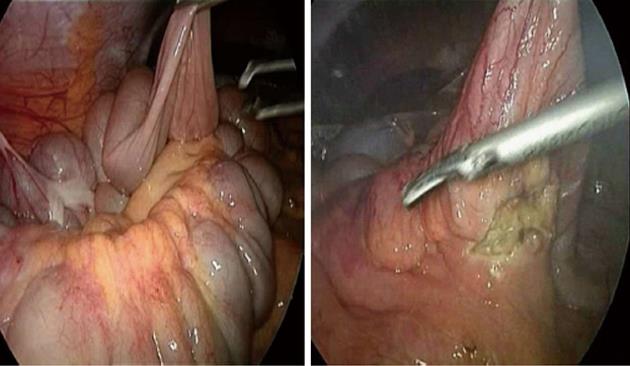

Furthermore the development of the therapeutic plan for IBD patients should also take into account the fact that the surgical approach to the abdomen has changed in recent years. Colectomies can be safely performed using a minimally invasive approach[8] to the great satisfaction of the patient (Figure 1). Most CD patients who have undergone laparoscopic ileo-cecal resection have been reported to choose a laparoscopic operation should the disease recur[9].

This is in agreement with data from the bariatric surgery where a steep increase in the request for surgical treatment of morbid obesity was observed after the development of minimally invasive procedures.

Surgery is certainly not the cure for CD, but is a viable therapeutic option and, given the potential advantages of the minimally invasive surgery, it shouldn’t be always put at the top of the pyramid of treatment. In selected subgroups of patients, early surgery is correlated with a more favorable surgical outcome and a laparoscopic ileo-cecal resection together with a fast track recovery protocol[10] may represent an appealing alternative to several years of medication. There is currently enough evidence to suggest a laparoscopic ileo-cecal resection as the gold standard in the management of CD patients with obstructive symptoms, but no significant evidence of active inflammation[11]. In fact, this group of patients (less than 40 cm affected bowel and appreciable symptoms but no imminent obstruction) respond well to medical treatment but will almost always require surgery during the course of their disease. A delayed surgical approach may not only increase the risk of septic complications but it may also reduce the possibility of performing a minimally invasive operation. CD patients who have undergone years of medication, and who present with a severely thickened bowel and mesentery due to marked inflammation and fibrosis, are candidates for more extensive resection with little chance of undergoing a minimally invasive procedure.

The quality of life for patients with UC is improved after colectomy[2]. Surgery is indicated in UC when medical therapy is ineffective, intractability being one of the most common reasons for proctocolectomy. Alternatively, steroid dependence which is not responsive to immunomodulatory drugs (including biologics), low compliance, multifocal dysplasia or high grade dysplasia, may represent indications for surgery. As for CD, delaying surgery may increase mortality and morbidity in UC. In patients who have undergone an emergency colectomy for UC, the risk of death increases substantially in the four to six months after surgery[4]. It has been recommended that about 85% of patients who do not respond to conventional steroid treatment within 6 d of hospitalization should undergo colectomy. A subgroup of these patients could alternatively be treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor “rescue” therapy, in accordance with the European Crohn and Colitis Organization guidelines[12]. Nevertheless, all of these criteria need to be considered in the light of the clinical characteristics of each individual patients, and a possible decision for surgery needs to be jointly assessed by an experienced gastroenterologist and surgeon on a daily basis. Furthermore, in UC the timing of surgery influences the surgical approach and vice versa: an emergency colectomy usually ends with a terminal ileostomy. This procedure is followed, generally after several months, by a completive proctectomy, restaurative pouch and lateral ileostomy. The third and last operation, the ileostomy closure, will be performed after a few months, provided the good condition of the ileo-anal pouch. However, in cases of planned elective surgery it will be possible to avoid one operation by performing a totally laparoscopic procto-colectomy and IPAA at the same time, followed by the closure of the lateral ileostomy (Figure 2).

Optimal care of patients with IBD continues to involve a great deal of judgment. Avoiding mortality and achieving a good quality of life are the guiding principles in the care of IBD patients. The decision to operate remains a difficult one and should take into account all the pros and cons of a planned “nice” laparoscopic resection compared to the symptomatic relief that may be achieved by primary, secondary or even tertiary medical therapy. Randomized controlled trials that include a large number of patients are required to establish the optimal timing for surgery in IBD.

Finally, but most importantly, unless severe complications indicate the need for emergency surgery, a decision for elective surgery must take into account not only the clinical characteristics of each patients but also the view of the patient. Indeed, the timing of surgery needs to be extensively discussed and approved not only by the gastroenterologist and surgeon, but also by the patient, who should be clearly informed of the risks and benefits of both medical and surgical therapy.

Laparoscopic surgery in IBD is safe and feasible. It offers both cosmetic advantages and some short term advantages, such as a possible reduction in perioperative complications[13]. Long term advantages include fewer incisional hernias and fewer adhesions[14] with a significant impact on female fertility in UC patients[15]. The minimally invasive procedure is the approach that is preferred in specialized centres. Considering its proven advantages and popularity amongst patients, it should be seen as a new strategic option when considering therapeutic alternatives in complicated IBD patients.

P- Reviewers Macrae FA, Rocha R S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Andrews HA, Lewis P, Allan RN. Prognosis after surgery for colonic Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1184-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Selinger CP, Leong RW. Mortality from inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1566-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roberts S, Williams JG, Goldacre MJ. Mortality in patient with and without colectomy admitted to hospital for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: record linkage studies. BMJ. 2007;335:1033. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oresland T. Review article: colon-saving medical therapy vs. colectomy in ulcerative colitis - the case for colectomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24 Suppl 3:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Scammell BE, Andrews H, Allan RN, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley MR. Results of proctocolectomy for Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1987;74:671-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Melville DM, Ritchie JK, Nicholls RJ, Hawley PR. Surgery for ulcerative colitis in the era of the pouch: the St Mark’s Hospital experience. Gut. 1994;35:1076-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sica GS, Iaculli E, Benavoli D, Biancone L, Calabrese E, Onali S, Gaspari AL. Laparoscopic versus open ileo-colonic resection in Crohn’s disease: short- and long-term results from a prospective longitudinal study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1094-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sica GS, Di Carlo S, Biancone L, Gentileschi P, Pallone F, Gaspari AL. Single access laparoscopic ileocecal resection in complicated Crohn’s disease. Surg Innov. 2010;17:359-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Spinelli A, Bazzi P, Sacchi M, Danese S, Fiorino G, Malesci A, Gentilini L, Poggioli G, Montorsi M. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopy combined with enhanced recovery pathway after ileocecal resection for Crohn’s disease: a case-matched analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:126-32; discussion p.132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D’Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571-607. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fleming FJ, Francone TD, Kim MJ, Gunzler D, Messing S, Monson JR. A laparoscopic approach does reduce short-term complications in patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Indar AA, Efron JE, Young-Fadok TM. Laparoscopic ileal pouch-anal anastomosis reduces abdominal and pelvic adhesions. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:174-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bartels SA, D'Hoore A, Cuesta MA, Bensdorp AJ, Lucas C, Bemelman WA. Significantly increased pregnancy rates after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1045-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |