Published online Apr 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2278

Revised: January 10, 2013

Accepted: January 29, 2013

Published online: April 14, 2013

Processing time: 145 Days and 15 Hours

Esophageal involvement by lichen planus (ELP), previously thought to be quite rare, is a disease much more common in women and frequently the initial manifestation of mucocutaneous lichen planus (LP). Considering that the symptoms of ELP do not present in a predictable manner, ELP is perhaps more under-recognized than rare. To date, four cases of squamous cell carcinoma in association with ELP have been reported, suggesting that timely and accurate diagnosis of ELP is of importance for appropriate follow-up. In this case report, a 69-year-old female presented with dysphagia and odynophagia. She reported a history of oral LP but had no active oral or skin lesions. Endoscopic examination revealed severe strictures and web-like areas in the esophagus. Histologic examination demonstrated extensive denudation of the squamous epithelium, scattered intraepithelial lymphocytes, rare eosinophils and dyskeratotic cells. Direct immunofluorescence showed rare cytoid bodies and was used to exclude other primary immunobullous disorders. By using clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data, a broad list of differential diagnoses can be narrowed, and the accurate diagnosis of ELP can be made, which is essential for proper treatment and subsequent follow-up.

Core tip: Lichen planus is an idiopathic disorder that generally affects middle-aged patients with clinical manifestations in the skin, mucous membranes, genitalia, hair, and nails. It is fairly common as a skin disease, affecting 0.5% to 2% of the population, the mouth being the most common site of involvement. We present one such case, diagnosed using clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data, and distinguished from primary immunobullous disorders by immunofluorescence.

- Citation: Nielsen JA, Law RM, Fiman KH, Roberts CA. Esophageal lichen planus: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(14): 2278-2281

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i14/2278.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2278

Lichen planus (LP) is an idiopathic disorder that generally affects middle-aged patients with clinical manifestations in the skin, mucous membranes, genitalia, hair, and nails[1]. Proposed etiologies include reaction to medication, Hepatitis C or other viral infections, bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, or autoimmune processes; however, the exact etiology and pathogenesis are still unknown[1,2]. It is fairly common as a skin disease, affecting 0.5% to 2% of the population[3], the mouth being the most common site of involvement[1]. Conversely, esophageal involvement by LP (ELP) has previously been considered quite rare, with fewer than 50 cases reported in the literature before 2008 and a predilection for women[4]. In 2010 the Mayo Clinic published a series of 27 cases within a 10-year period, suggesting that it is perhaps more under-recognized than rare and often the initial manifestation of mucocutaneous LP[1]. Subsequently, there is often a significant delay between onset of symptoms, dysphagia being the most common, and diagnosis[3]. Considering that four cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in association with ELP have been confirmed to date[5-7], the seriousness of this diagnostic delay should move physicians to take greater precautions to rule out ELP. We present one such case, diagnosed using clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data, and distinguished from primary immunobullous disorders by immunofluorescence.

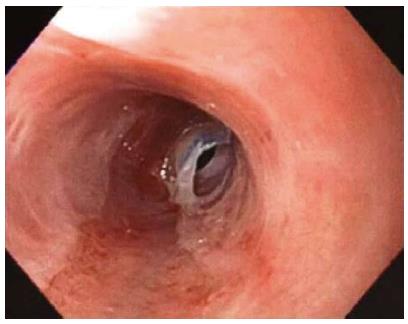

A 69-year-old female presented with dysphagia and odynophagia that had been ongoing for years. She reported a history of oral LP, but had no active oral or skin lesions, and a previously normal upper gastrointestinal series X-ray. The patient initially declined endoscopy and took proton-pump inhibitors without benefit. Later endoscopic examination revealed severe strictures and rings throughout the length of the esophagus with web-like areas; however, the gastroesophageal junction was spared and appeared essentially normal. The mucosa showed severe, diffuse sloughing with passage of the endoscope (Figure 1). Esophageal biopsy was obtained for routine histology and submitted in 10% buffered formalin. Esophageal dilation was not performed.

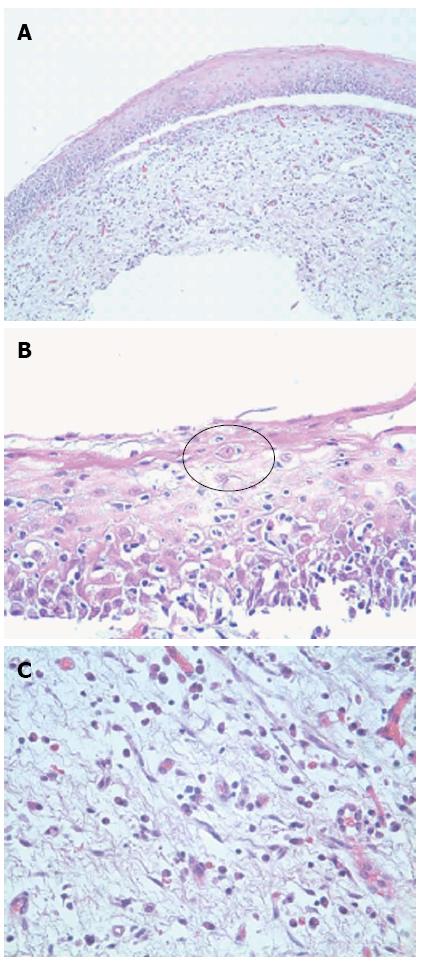

Histologically, the esophageal tissue demonstrated extensive denudation of the surface epithelium. The mucosa was detached from the subepithelial tissue in several areas without preservation of the basal layer (Figure 2A). Where attached, the squamous (esophageal) epithelium was somewhat atrophic with diffuse spongiotic change, scattered intraepithelial lymphocytes, rare eosinophils, and dyskeratotic cells (Civatte bodies) (Figure 2B, black circle). The subepithelial tissue showed edema and a diffuse lichenoid infiltrate including lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasional mast cells (Figure 2C). There was no evidence of Candida by virtue of a negative alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff stain. The absence of significant intraepithelial acute inflammation and/or viral cytopathic effect in conjunction with the lichenoid infiltrate and Civatte bodies excluded a viral infection. However, while a definitive diagnosis of LP could not be made on routine histology alone, it was suggested. The patient was promptly re-biopsied a month later from the middle and upper esophagus. The biopsies were submitted in Zeus transport media for immunofluorescence.

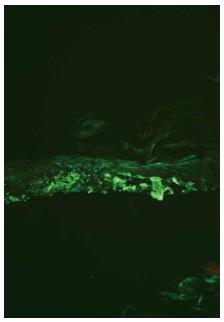

Direct immunofluorescence revealed fibrillar deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane zone (Figure 3), characteristic of but not specific for LP. IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 showed rare cytoid bodies in the same areas without any evidence of a primary immunobullous disorder such as pemphigus or pemphigoid. The basic histomorphology in conjunction with the clinical history of oral lichen planus and the negative immunofluorescence excluded immunobullous disorders, such as esophageal pemphigus vulgaris.

First described by Al-Shihabi et al[8] and Lefer[9] simultaneously but separately, over 80 cases of ELP have been reported in both English and foreign-language literature to date, only 8 of which are male[3]. Multiple retrospective studies have shown that ELP is under-recognized[1,3,10], since the esophageal symptoms can present before, concurrently, or develop after the diagnosis of extra-ELP[1,3]. In his review of 79 patients that developed ELP, Fox noted that 14 patients developed ELP as the first and only manifestation of LP. Oral LP has been long known to predispose 2%-3% of cases to the development of oral SCC[10]; however, with documentation of 4 cases of ELP progressing to esophageal SCC, early diagnosis and accurate therapy for ELP patients has become a more serious issue[2]. One of these esophageal SCC cases was reported in a series of 8 patients, the mean delay between symptom onset and diagnosis of which was 27 mo[6]. Additionally, Katzka et al[1] found in his review of 27 patients with ELP that this delay in diagnosis not only resulted in increased length of time with symptoms (range: 0.33-30 years, mean: 4.72 years) but also increased the number of failed treatments before diagnosis (range: 0-15, mean: 2.5), including prior dilatations, medications such as proton-pump inhibitors, and fundoplication.

Because the symptoms of ELP are not distinctive, many clinicians recommend physicians maintain a low threshold for performing endoscopies to rule out ELP in patients experiencing dysphagia with a history of mucocutaneous LP[3,10]. Esophageal sloughing and refractory strictures in a middle-aged or older female even in the absence of extra-ELP should raise ELP as a diagnostic consideration, as less than half of those with mucosal LP will exhibit concomitant skin lesions[2,10]. Additionally, easy peeling of the esophageal mucosa with minimal contact and formation of “tissue paper-like membranes” is a frequently observed characteristic[11]. Suspecting a more common culprit such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), endoscopists oftentimes focus on the lower esophagus and could potentially miss proximal lesions caused by ELP[3]. In general, GERD can be distinguished from ELP by the sparing of the gastroesophageal junction in ELP[3]. In a study using magnification chromoendoscopy on 24 consenting patients with cutaneous and/or oral LP, the University Medical Center Utrecht (Netherlands) found that 5 (21%) had ELP, 5 (21%) had GERD, and 7 (29%) had both, with no differences in symptoms amongst the groups[10]. Early diagnosis may be improved by new diagnostic modalities such as chromoendoscopy or magnification endoscopy[2].

The final diagnosis can be reached by combining the historic, endoscopic, and histologic data; whereas the routine light microscopy, while unusual, is not pathognomonic for ELP. The most indicative characteristics of ELP are a lymphohistiocytic interface inflammatory infiltrate and dyskeratotic cells (Civatte bodies)[10]. Other common disorders that affect both esophagus and skin are bullous disorders, such as pemphigus vulgaris, paraneoplastic pemphigus, epidermolysis bullosa aquistia, mucous membrane pemphigoid, bullous pemphigoid, and Hailey-Hailey disease[3]. The lack of specific immunofluorescent staining in conjunction with the subepithelial as opposed to suprabasal separation and history of oral LP clearly excluded the bullous disorders in this case[3,11]. While pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) shows similar histology in cutaneous biopsies, there are no published reports of PLC occurring on mucosal surfaces such as the esophagus[12]. Even more importantly, the patient had no cutaneous lesions or history to support this diagnosis. A viral cause was excluded due to the lack of erosion/ulceration, viral cytopathic effect, and acute inflammation. Further, Civatte bodies are not typically seen in viral infections. More remote possibilities, such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and toxin-associated damage, are characterized by apoptosis, which is absent in this case. Furthermore, Civatte bodies, while characteristic of ELP, are not seen in GVHD or toxic-injury, such as caused by the drug mycophenolate which essentially mimics GVHD. Finally, historical data showing a lack of transplant history or mycophenolate use serves to remove GVHD and/or mycophenolate from a diagnostic consideration here[12]. By taking into consideration the various diagnostic methods and suggestions, other possible diagnoses can be ruled out, and the diagnostic delay of ELP can be decreased, which is essential for appropriate treatment and clinical follow-up, potentially preventing more serious sequelae, including SCC[2].

P- Reviewers Decorti G, Gassler N S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Katzka DA, Smyrk TC, Bruce AJ, Romero Y, Alexander JA, Murray JA. Variations in presentations of esophageal involvement in lichen planus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:777-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Izol B, Karabulut AA, Biyikoglu I, Gonultas M, Eksioglu M. Investigation of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement and H. pylori presence in lichen planus: a case-controlled study with endoscopic and histopathological findings. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1121-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fox LP, Lightdale CJ, Grossman ME. Lichen planus of the esophagus: what dermatologists need to know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:175-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chandan VS, Murray JA, Abraham SC. Esophageal lichen planus. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1026-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schwartz MP, Sigurdsson V, Vreuls W, Lubbert PH, Smout AJ. Two siblings with lichen planus and squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1111-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chryssostalis A, Gaudric M, Terris B, Coriat R, Prat F, Chaussade S. Esophageal lichen planus: a series of eight cases including a patient with esophageal verrucous carcinoma. A case series. Endoscopy. 2008;40:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Benni M, Areni A, Scialpi C, Miglioli M, Di Febo G. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in esophageal lichen planus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:596-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Shihabi BM, Jackson JM. Dysphagia due to pharyngeal and oesophageal lichen planus. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96:567-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lefer LG. Lichen planus of the esophagus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:267-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Quispel R, van Boxel OS, Schipper ME, Sigurdsson V, Canninga-van Dijk MR, Kerckhoffs A, Smout AJ, Samsom M, Schwartz MP. High prevalence of esophageal involvement in lichen planus: a study using magnification chromoendoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:187-193. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ukleja A, DeVault KR, Stark ME, Achem SR. Lichen planus involving the esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2292-2297. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Montgomery EA, Voltaggio L. Biopsy interpretation of the gastrointestinal tract mucosa: Volume 1: Non-Neoplastic. 2nd ed. Pine JW, editor. China: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2012; 21-35. |