Published online Apr 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2154

Revised: December 8, 2012

Accepted: December 27, 2012

Published online: April 14, 2013

Processing time: 234 Days and 13 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the location, histopathology, stages, and treatment of gastric cancer and to conduct survival analysis on prognostic factors.

METHODS: Patients diagnosed with of stomach cancer in our clinic between 2000 and 2011, with follow-up or a treatment decision, were evaluated retrospectively. They were followed up by no treatment, adjuvant therapy, or metastatic therapy. We excluded from the study any patients whose laboratory records lacked the operating parameters. The type of surgery in patients diagnosed with gastric cancer was total gastrectomy, subtotal gastrectomy or palliative surgery. Patients with indications for adjuvant treatment were treated with adjuvant and/or radio-chemotherapy. Prognostic evaluation was made based on the parameters of the patient, tumor and treatment.

RESULTS: In this study, outpatient clinic records of patients with gastric cancer diagnosis were analyzed retrospectively. A total of 796 patients were evaluated (552 male, 244 female). The median age was 58 years (22-90 years). The median follow-up period was 12 mo (1-276 mo), and median survival time was 12 mo (11.5-12.4 mo). Increased T stage and N stage resulted in a decrease in survival. Other prognostic factors related to the disease were positive surgical margins, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, cardio-esophageal settlement, and the levels of tumor markers in metastatic disease. No prognostic significance of the patient’s age, sex or tumor histopathology was detected.

CONCLUSION: The prognostic factors identified in all groups and the proposed treatments according to stage should be applied, and innovations in the new targeted therapies should be followed.

- Citation: Selcukbiricik F, Buyukunal E, Tural D, Ozguroglu M, Demirelli F, Serdengecti S. Clinicopathological features and outcomes of patients with gastric cancer: A single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(14): 2154-2161

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i14/2154.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2154

Despite the innovations in treatment, gastric cancer still remains a mortal disease[1]. Patient, tumor and treatment factors determine the prognosis. In recent years, when there has been an overall reduction in gastric cancer, a moderate increase in proximal stomach and esophagogastric junction region adenocarcinoma has been observed[2]. While the basic treatment of gastric cancer is complete resection and, following this treatment, if necessary, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, the standard treatment in metastatic patients is chemotherapy and palliative treatment. Currently, studies on neoadjuvant therapy are ongoing.

In the intergroup trial (INT 0116), which was a randomized phase III trial, the effectiveness of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was compared with the monitoring group. In that study, 556 patients were randomized to the adjuvant therapy group, in which the five-year survival rate was 50%, or the surgery group, in which it was 41% (HR = 1.35). That study established the standard adjuvant therapy in gastric cancers. After Macdonald’s research[3], with close to ten years’ follow-up demonstrating that survival was 41% after surgery and 50% after adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, this treatment approach has become the standard treatment. However, many studies have been conducted regarding systemic adjuvant treatment[4].

One of the most well-known randomized trials on neoadjuvant treatment for gastric cancer has been reported by Jackson et al[5] and Cunningham et al[6]. The MAGIC study comparing neoadjuvant treatment to surgery alone is the most important work demonstrating a survival advantage for the neoadjuvant treatment approach.

Among the forms of treatment of advanced gastric cancer, the best supportive therapies are single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy and targeted therapies. The five-year survival for stomach cancer is approximately 78%-95% in stage IA, 58%-85% in stage IB, 34%-54% in stage II, 20%-37% in stage IIIA, 8%-11% in stage IIIb, and 5%-7% in stage IV. Wagner et al[7] demonstrated that combination chemotherapy is more beneficial than single-agent chemotherapy (HR = 0.82, 95%CI: 0.74-0.90) Survival with combination treatments vs single-agent chemotherapy is 6.7 mo vs 8.3 mo. Combination chemotherapies do not provide a significant increase in toxicity but do confer a slight difference in treatment-related mortality (1.1% vs 1.5%).

Cisplatin-fluorouracil (CF) is the most commonly used regimen for advanced gastric cancer. In 6 basic studies that investigated CF for gastric cancer, the response rate (RR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were similar between the CF groups and control groups. In these studies PFS was in the range of 3.7 to 4.1 mo, the median survival was 7.2 to 8.6 mo, and the 2-year survival was 7% to 10%. Addition of docetaxel to CF resulted in a survival advantage[8]. Kang et al[9] showed similar results for cisplatin ± capecitabine compared with CF. The REAL-2 study compared oxaliplatin combination regimens with regimens containing cisplatin and determined that the latter conferred the best median survival. In phase III of the REAL-2 study, which analyzed the cisplatin ± 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) combination in advanced gastric cancer, the best median survival was 9.9 mo, and two-year survival was 15% [epirubicin-cisplatin-5-FU (ECF) 9.9 mo, cisplatin oxaliplatin 5-FU 9.3 mo, epirubicin oxaliplatin capecitabine cisplatin 9.9 mo and epirubicin-oxaliplatin-capecitabine 11.2 mo][10].

The TAX 325 study established the standard of phase III trials in advanced gastric cancer. Randomized patients were divided into two arms[8]. The recurrence rate of the docetaxel-cisplatin-fluorouracil (DCF) arm was reduced approximately 32% compared to the CF arm, and time to progression was 5.6 mo in the CF arm vs 3.7 mo in the DCF arm (P = 0.0004).

HER2 overexpression or amplification is detected in 20% of all gastric cancers. In the ToGA trial in epidermal growth receptor-positive gastric cancer patients, in the first-line treatment, chemotherapy alone was compared with the use of trastuzumab + chemotherapy. Time to progression was 5.5 mo in the patients who received chemotherapy alone 6.7 mo in the chemotherapy + trastuzumab group (P = 0.0002). The median survival rate of the patients receiving chemotherapy alone was 11.1 mo vs 13.8 mo among patients receiving trastuzumab and chemotherapy together[11].

The records of patients with gastric cancer followed by the Department of Medical Oncology were analyzed retrospectively. Patients were recruited to the study if they were treated between 2000 and 2011 by the outpatient clinic. They were followed up by no treatment, adjuvant therapy, or metastatic therapy. We excluded from the study any patients whose laboratory records lacked the operating parameters. According to these criteria, the study sample consisted of the remaining 796 patients (552 male, 244 female, mean age at diagnosis: 58 years).

Patient age, sex, symptoms at diagnosis, localization of the tumor, operative details, histopathological features, AJCC 2010 TNM stage, treatment decisions, sites of metastasis, tumor marker levels at baseline, the presence of adjuvant radiotherapy, PFS, disease-free survival (DFS), and OS were recorded.

The type of surgery in patients diagnosed with gastric cancer was total gastrectomy, subtotal gastrectomy or palliative surgery. Patients with indications for adjuvant treatment were treated with adjuvant and/or radio-chemotherapy. The number of patients who received adjuvant treatment was 352 (44.2%). Initially, 394 (49.4%) patients were admitted with metastases, and these patients received chemotherapy. No treatment was initially suggested for 48 patients (6.4%). Each series of chemotherapy treatments received by the patients was recorded.

Statistical analysis were performed with SPSS for Windows ver. 15.0 (standard version). Quantitative (numerical) data are reported as the mean ± SD. For two-group comparisons, we used the paired Student’s t-test or, when necessary, the Mann-Whitney U test. For non-numerical data, when suitable for 2 × 2 contingency tables, Yates’ corrected χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used. Correlations between numerical parameters were analyzed with Spearman’s (p) correlation test. For the comparison of groups, Student’s t-test or, when needed, one-way or multi-factor analysis of variance was used.

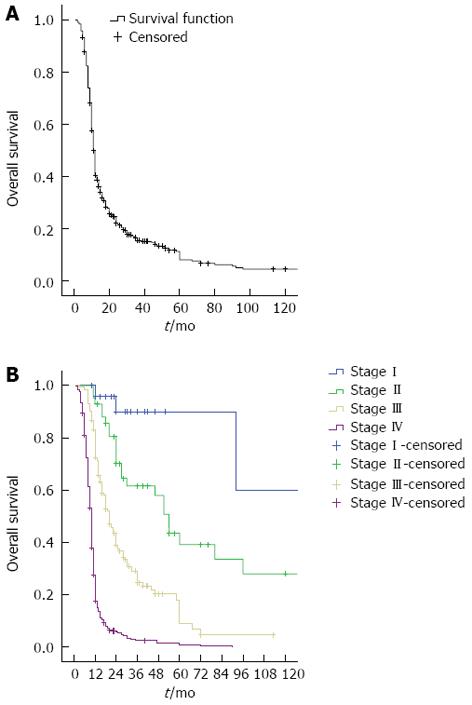

In this study, outpatient clinic records of patients with gastric cancer diagnosis were analyzed retrospectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the 796 gastric cancer cases included in the study were as follows: initial symptoms were dyspeptic symptoms, (39.3%), abdominal pain (24.8%), nausea and vomiting (16.3%), weight loss (7.5%), bleeding (6.4%) and acute abdominal pain (1.6%). The median follow-up period was 12 mo (1-276 mo), the median survival was 12 mo (11.5-12.4 mo), and the 5-year survival rate was 11%. The OS curve is given in Figure 1A, and the survival curve according to stage is given in Figure 1B. The median survival of metastatic patients was 10 mo, compared to 92 mo in stage I patients (P < 0.0001). The demographic data of the 796 gastric cancer patients are given in Table 1. While the 5-year survival rate with lymphovascular invasion was 18%, this rate was 31% in the patients without lymphovascular invasion (LVI) (P < 0.0001). The 5-year survival of patients with perineural invasion (PNI) was 16%, compared to 33.6% without PNI (P < 0.006). The 5-year survival rate for patients with negative surgical margins was 28%, which was significantly higher than those with positive margins (P < 0.0001). All patients with positive margins died within 5 years.

| Age (yr) | Median | 58 (22-90) |

| Sex | Male | 552 (69) |

| Female | 244 (31) | |

| Median follow-up time | 12 mo (range: 1-276 mo) | |

| Median survival | 12 mo (range: 11.5-12.4 mo) | |

| Tumor location | Pyloric + antrum | 362 (45.4) |

| Large and small curvature | 252 (31.6) | |

| Cardio-esophageal | 97 (12.2) | |

| Diffuse | 9 (1.1) | |

| Stage | Stage I | 29 (3.6) |

| Stage II | 43 (5.4) | |

| Stage III | 195 (24.5) | |

| Stage IV | 393 (49.3) | |

| Type of surgery | Total gastrectomy | 265 (33.2) |

| Subtotal gastrectomy | 174 (21.8) | |

| Inoperable/palliative | 341 (42.8) | |

| Treatment | Adjuvant | 352 (44.2) |

| Metastatic | 394 (49.4) | |

| Untreated follow-up | 50 (3.9) | |

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma (intestinal type) | 493 (61.9) |

| Signet ring cell (diffuse) | 254 (31.9) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 24 (3) | |

| Others | 8 (1.1) | |

| In metastasis | Peritonitis carcinomatosa | 193 (24.2) |

| Liver | 169 (21.2) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 73 (9.2) | |

| Liver + peritoneum | 35 (4.4) | |

| Lung | 28 (3.5) | |

| Pleural effusion + acid | 24 (3) | |

| Bone | 23 (2.9) | |

| Others | 17 (2.1) | |

| Recurrence in | Peritonitis carcinomatosa | 61 (40.1) |

| Liver | 36 (23.7) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | 24 (15.8) | |

| Local | 14 (9.2) | |

| Pleural/lung | 12 (7.9) | |

| Others | 5 (5) |

While the 5-year survival of patients with initially normal crystalline egg albumen (CEA) level was 14.8%, patients with high CEA level all died within 5 years (P < 0.012). Five-year survival among patients with initial normal carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) level was 17.5% in all groups, but for the group with high CA 19-9, 5-year survival was 1.2% (P < 0.2). In the evaluation of only stage 4 patients, the tumor marker of high baseline CA 19-9 reached prognostic significance (P < 0.03). Gender (P < 0.2) and histological subtype had no effect on prognosis (P < 0.5). In multivariate analysis, tumor stage had significant effects on overall survival (P < 0.0001) and surgical margin (P < 0.001).

The approaches used for gastric cancer treatment are shown in Table 2. A group of patients with gastric cancer without metastasis was followed without medication, and chemotherapy was applied to the others. DFS for approaches to non-metastatic gastric cancer is given in Table 3. The mean survival of the non-treated follow-up group was significantly higher than other groups, primarily because of the survival of the stage I patients (P = 0.007). Table 4 shows the effects of chemotherapy or supportive treatment in patients with metastasis. Here, the time to the first progression after initial treatment was defined as PFS1, and the time to the second progression (after the second treatment) was defined as PFS2. PFS1 for patients receiving DCF was 6.56 mo, which was similar to other chemotherapy regimens. The first time to progression in patients receiving supportive therapy was 3.85 mo. After a second round of chemotherapy was started because of progression, DCF significantly prolonged PFS2. Eventually, DCF treatment of metastatic gastric cancer patients significantly prolonged time to progression compared to other approaches. Table 5 compares the results of the 1st and 2nd series of treatments for metastatic cancer. In the first metastatic series, DCF treatment was superior to all other treatments, and the greatest statistical superiority was to ECF and supportive care. DCF was therefore the preferred choice for first-line therapy in our study. A superior PFS was obtained with DCF compared to all other approaches. Supportive treatment was the preferred approach in the second series of our study. This was because of the frequent selection of DCF in the first series and the inability to repeat DCF after progression.

| Treatment | ||

| Adjuvant therapy | 5-FU-LV | 222 (27.9) |

| 5-FU-LV/cisplatin | 43 (5.4) | |

| Untreated follow-up | 58 (7.3) | |

| Others | 17 (2.1) | |

| Metastatic series 1 | 5-FU-LV | 32 (4) |

| DCF | 152 (19.1) | |

| ECF | 77 (9.7) | |

| 5-FU-LV/cisplatin | 121 (15.2) | |

| Palliative treatment | 112 (14.1) | |

| Cisplatin/capecitabine | 20 (2.5) | |

| Others | 31 (3.9) | |

| Metastatic series 2 | DCF | 31 (3.9) |

| 5-FU-LV/cisplatin | 19 (2.4) | |

| ECF | 14 (2.3) | |

| Irinotecan/cisplatin | 17 (2.1) | |

| Supportive | 267 (33.5) | |

| Others | 32 (4) |

| Therapeutic approach | n | Average (mo) | Standard deviation | Minimum (mo) | Maximum (mo) |

| First series of chemotherapy and time to progression | |||||

| DCF | 152 | 6.56 | 2.869 | 1 | 18 |

| ECF | 77 | 4.56 | 9.021 | 1 | 48 |

| CF | 121 | 4.15 | 5.546 | 1 | 39 |

| Supportive | 112 | 3.85 | 9.951 | 2 | 60 |

| Others | 38 | 5.24 | 11.954 | 1 | 60 |

| Second series of chemotherapy and time to progression | |||||

| DCF | 31 | 4.38 | 3.921 | 2 | 15 |

| ECF | 14 | 3.71 | 2.443 | 2 | 10 |

| CF | 19 | 3.76 | 3.914 | 3 | 18 |

| Supportive | 267 | 3.39 | 1.871 | 1 | 12 |

| Others | 17 | 3.75 | 1.528 | 1 | 7 |

| 1st-series treatment approach | P value | 2nd-series treatment approach | P value |

| DCF vs 5-FU-LV | 0.043 | DCF vs ECF | 0.050 |

| DCF vs others | 0.010 | DCF vs Supportive | 0.042 |

| DCF vs Supportive | < 0.001 | Supportive vs ECF | 0.500 |

| DCF vs ECF | < 0.001 | DCF vs others | 0.605 |

| DCF vs CF | 0.480 | Irinotecan/Cisp vs ECF | 0.423 |

| ECF vs CF | 0.960 | Supportive vs Irinotecan/Cisp | 0.100 |

| Supportive vs ECF | < 0.01 | DCF vs Irinotecan/Cisp | 0.672 |

Our study population included 70 patients under age 40 (8.8%), 510 patients between 40 and 65 (64%), and 216 patients over the age of 65 (27.2%). A difference in survival according to age was not observed (P = 0.8). In the survival evaluation related to the tumor localization, patients with cardio-esophageal tumors (P < 0.002) and patients with linitis plastica (P < 0.05) showed the worst survival.

This study was designed to determine the prognostic factors of gastric cancer based on tumor location, histological type, stage at diagnosis, and the phases of evaluation of treatment methods.

Talamanti et al[12] explored the relationship between tumor localization and prognosis. Because proximal tumors are more insidious, delay diagnosis, invade more deeply and metastasize to lymph nodes more frequently compared to distal tumors, Talamanti et al[13,14] reported a poorer prognosis for proximal tumors. Furthermore, they demonstrated that the placement of the disease in Caucasian populations significantly affects the prognosis and that tumors with this location show a poor prognosis. In our study, proximal tumors were associated with a worse prognosis than distal tumors, and the frequency of proximal tumors increased significantly after 2005. Proximal tumors required extended gastrectomy, D2 dissection and splenectomy. In this respect, patients with proximal tumors are in serious danger of mortality and morbidity related to surgery as well as delayed diagnosis and increased depth of invasion.

Machara et al[15] and Persiani et al[16] demonstrated the relationship between young age and poor prognosis, but in our study there was no correlation between age and prognosis. In our series this rate was 56% vs 44%. In some studies, the depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant metastasis were the main prognostic factors[17]. In our study, the 5-year survival rate of 16% for patients with PNI was significantly lower than those without PNI. Although it is not lymph node metastasis, lymphovascular invasion is a poor prognostic parameter. Patients with LVI had significantly lower 5-year survival than patients without LVI. Ding et al[18] revealed that lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinoma is the most important prognostic factor. In our study, if the node period was increased, survival decreased, and in patients with N2 gastric cancer, 5-year survival decreased to 5%. In the german gastric cancer study, Siewert et al[19] demonstrated, by analyzing the 10-year results of 1654 patients with curative gastrectomy, that lymph node status, invasion depth, the development of postoperative complications, distant metastases and tumor size are associated with prognosis. Maruyama et al[20] showed in 4734 gastric cancer cases that depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, macroscopic type, localization and histological type are the most important prognostic factors. In our study, while a correlation with the number of lymph no des removed was not detected, increased node stage affected survival.

The ratio of the number of metastatic lymph nodes to removed lymph nodes is an important prognostic factor. Ding et al[20] demonstrated that the increase of this ratio decreases survival. In our series, as the number of metastatic lymph nodes increased, the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year survival rates were 97%, 74%, and 63% for N0; 87%, 34.8%, and 18.5% for N1; 73%, 16.4%, and 5% for N2; and 78%, 39% and 0% for N3. In addition, lymph node-negative patients, despite having better prognosis than lymph node-positive patients, experienced recurrence and short survival. After Lauren[21] demonstrated that gastric carcinoma has two separate histologies, an intestinal and a diffuse type, the distinct effect of tumor histology on prognosis was investigated. While the intestinal type shows a better prognosis, both histological types can cross the stomach wall and reach the serosal surface and may act metastatic. No difference in survival was observed in any of our patients according to histological type.

When the survival analysis was conducted separately according to the zone of metastasis, we found no differences in survival. However, if carcinoma peritonei was detected, survival averaged less than 8 mo. The role and value of metastasectomy for gastric cancer is not clear. Although there are too few data to draw conclusions about the effect of metastasectomy on survival, Kerkar et al[22] found 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival rates in 436 patients with liver metastasectomy of 62%, 30% and 26.5%, respectively. Our series included 8 gastric cancer patients with liver metastases who underwent metastasectomy, and the survival data obtained from these patients were consistent with that study. In another study, in the 23-mo follow-up of 43 patients with solitary pulmonary resection, 15/43 (35%) patients were without evidence of disease, and 5-year survival was reported as 33% for gastric cancer[23]. In our series, there were no cases of metastasectomy for pulmonary metastases of gastric cancer. Dewys et al[24] reported that the gastric cancer symptoms are often nonspecific but can include lumen obstruction, bleeding or acute abdominal pain. Seventy percent of patients initially had symptoms such as abdominal-epigastric pain or discomfort, followed by symptoms such as weight loss, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis and melena. The initial symptoms in our study were consistent with the literature.

In one study, serum CEA was elevated in one-third of gastric cancer patients at diagnosis. Although the CEA level in gastric cancers has low sensitivity as a prognostic marker, high levels are related to the phase of the disease. Higher levels of CA 19-9 and CEA are more sensitive as a combined prognostic factor[25]. Although in our study population, the initially determined marker values demonstrated no relationship with survival, the prognostic significance of high CA 19-9 at diagnosis in stage IV patients emerged. CA 19-9 was not correlated with the level of CEA-free survival. In gastric cancer, as the stage of the disease progresses, the level of CEA increases. In localized cases, CEA increases by 14%-29%, whereas in patients with metastatic cancer, this figure can reach 85%. Haglund et al[26] and Koga et al[27] reported a 48% sensitivity of CA 19-9 in predicting the prognosis of gastric cancer. Kago and colleagues found high levels of CA 19-9 in 20.9% of stomach cancer patients, including 37% of stage 4 patients and 69.2% of patients with liver metastases.

The median survival of patients with metastatic cancer in this study was 10 mo, and for stage I patients the median survival was 92 mo. We compared our data to the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year free survival of gastric cancer according to the data Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) study, covering the years 1975-2008 and a total of 10 601 patients with resected gastric cancer[28], and found that 1-year survival in stage I, II and III patients of our series was greater, the life span of patients with stage IV; 3-year survival in stage I, II and III patients in our series was greater, whereas stage IV patients showed a worse outcome in our series, and 5-year survival in stage I, II and III patients in our series was better, whereas stage IV patients showed a worse outcome. Comparing all of our study population’s survival data with data from the SEER study showed that stage IV patients showed similar survival rates, whereas stage I, II, and III patients seemed to have longer survival times in this series. While local or locoregional recurrence after surgical resection of gastric cancer is a current problem, adjuvant treatment should be administered to patients. Adjuvant therapy, especially in node-positive disease, gives better results. Adjuvant radiotherapy and/or adjuvant chemotherapy has been designed for this purpose in phase III trials.

In a randomized phase III trial, the Intergroup trial (INT 0116), the effectiveness of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was compared with the observation group and a group treated only with surgery. For resected stage IB-IV (M0), a 5-treatment strategy was planned for gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma patients, and at the same time, radiotherapy was used. That study reported a statistically significant advantage in median survival. In the current study, 5-year survival for patients receiving adjuvant therapy was 50%, compared to 41% for the surgery group (HR = 1.35)[3]. In our study, 246 patients were evaluated in terms of the success of adjuvant treatment. A total of 199 patients received adjuvant therapy, but in 99 patients the indication for treatment had not been set. Comparing the types of treatment or follow-up in patients without metastasis at the beginning of the study, the non-treatment group had significantly longer survival than other groups, and significant differences were not found between the other groups. The reason for this most likely is that the patients who received non-adjuvant therapy were already in stage IA, and a longer survival time was expected for these patients. For patients with an indication for adjuvant treatment who underwent a Macdonald regimen, 5-year survival rates were in 90% in stage I, 50% in stage II and 20% in stage III, which are consistent with the literature. The local recurrence rate in the group receiving chemoradiotherapy was 19%. The regional relapse rate was 65% against the 72%. Patients tolerated the regime well. Other adjuvant therapies did not confer a significant increase in survival.

Although some studies have assessed preoperative chemoradiotherapy, the numbers of patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were not large enough for statistical analysis. Compared with general treatment forms in advanced gastric cancer, approaches such as single-agent chemotherapy, combination chemotherapy and targeted therapies can be considered the best adjuvant treatments. Wagner et al[29], in a meta-analysis, compared the best adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy regimens and evaluated the median and overall survival rates. Four quality-of-life questionnaires were used to compare chemotherapy with the best supportive care, and chemotherapy was considered better at 12 mo than at 6 mo. In our study, the chemotherapy regimens were superior to supportive care, in accordance with the literature. DCF was used as a metastatic first-line treatment and produced a PFS of 6.5 mo, compared to 4.5 mo using ECF, 4.1 mo using CF, and 3.8 mo using supportive care. In the evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment on survival, using DCF the overall survival was 9.5 mo, 6.5 mo using EC, 5.1 mo using CF and 4.8 mo in patients with only supportive treatment. Any progression under treatment with chemotherapy or supportive care in the second series of treatments was noted, and the PFS2 for DCF was 4.3 mo, for ECF was 3.7 mo and for supportive therapy was 3.3 mo. Considering the effect of combination chemotherapy on PFS, the DCF regimen was superior to all other treatments. Our study was consistent with the results of the TAX 325 study of Van Cutsem et al[8], which created the standard of advanced gastric cancer care. In their study, DCF was superior to CF in overall survival as well as in time to progression.

Our study evaluated patients treated with different chemotherapy regimens, and DCF showed superior efficacy in all arms in both PFS and overall survival.

The combination of cetuximab with docetaxel and cisplatin does not significantly affect time to progression or overall survival[30]. Lapatinib, the first dual inhibitor of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-1) and HER-2, has been investigated in two phase II studies as a single therapeutic agent, but no survival advantage was observed[31]. Gefitinib and erlotinib, two tyrosine kinase inhibitors, have been used as a combination treatment for cancer, and in extensive studies, a RR of 9% was obtained[32]. Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor A, was investigated in the AVAGAST study. The combination of bevacizumab + CC conferred no significant survival advantage compared to CC alone. In another study, IC was combined with bevacizumab, and a significant advantage was not observed compared to IC alone[33]. Sunitinib is an oral inhibitor of VEGFR1, -2, and -3, PDGFR-α and -β and c-kit. Use of second-line sunitinib in phase II trials produced an overall survival of 47.7 wk. In another phase II study using sorafenib in combination with docetaxel and cisplatin, clinical activity was observed[34]. Everolimus, an oral inhibitor of mTOR, has been effective in gastric cancers in phase I and phase II trials[35].

Due to the limited number of patients with targeted therapy in this study, HER-2 status and the effectiveness of trastuzumab could not be assessed. Efficacy assessments could not be made also because targeted therapies such as trastuzumab were not used in our series. When HER-2 receptor status is analyzed routinely in stomach cancer patients, targeted therapy may be evaluated more completely.

In spite of the development of oncology treatments, gastric cancer still has a high mortality. All the prognostic factors should be evaluated before planning the treatment of gastric cancer. It should be kept in mind that there are new treatment modalities for gastric cancer.

In this study, the authors retrospectively evaluated gastric cancer patients treated in our clinic during the last 10 years. The prognostic factors for these patients were identified and the treatment plan made according to these factors. The treatments of the patients and their survival were evaluated and compared with the literature. Additionally, the importance of targeted therapy is emphasized.

This study has provided new insight into gastric cancer. Properly identifying the prognostic factors and planning the treatment and follow-up according to these factors is suggested. This study has shown that mortality is high in metastatic patients and that clinicians should be more encouraged to use targeted therapy.

Based on the results, molecular features of metastatic patients, such as human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER-2) receptor status, will be identified and targeted therapy principles will be developed.

HER-2 is a member of the epidermal growth factor family. It is involved in tumor proliferation, metastasis and poor prognosis. If a patient is HER-2 positive, then the anti-HER-2 antibody trastuzumab can be useful. Authors need further clinical studies to evaluate other targeted therapy modalities.

The authors have identified the prognostic features of gastric cancer patients and compared the standard treatment modalities. They note the importance of molecular studies in gastric cancer patients, and they predict that targeted therapy will be a part of the standard treatment in the future.

P- Reviewer Guo JM S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Kim JP, Lee JH, Kim SJ, Yu HJ, Yang HK. Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors in 10 783 patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Salvon-Harman JC, Cady B, Nikulasson S, Khettry U, Stone MD, Lavin P. Shifting proportions of gastric adenocarcinomas. Arch Surg. 1994;129:381-38; discussion 381-38;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2465] [Cited by in RCA: 2436] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lordick F, Ridwelski K, Al-Batran SE, Trarbach T, Schlag PM, Piso P. [Treatment of gastric cancer]. Onkologie. 2008;31 Suppl 5:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jackson C, Mochlinski K, Cunningham D. Therapeutic options in gastric cancer: neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs postoperative chemoradiotherapy. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21:1084-107; discussion 1090, 1084-107; 1101. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4899] [Cited by in RCA: 4606] [Article Influence: 242.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wagner AD, Grothe W, Behl S, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD004064. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, Rodrigues A, Fodor M, Chao Y, Voznyi E. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991-4997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1331] [Cited by in RCA: 1457] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kang YK, Kang WK, Shin DB, Chen J, Xiong J, Wang J, Lichinitser M, Guan Z, Khasanov R, Zheng L. Capecitabine/cisplatin versus 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:666-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 544] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chong G, Cunningham D. Can cisplatin and infused 5-fluorouracil be replaced by oxaliplatin and capecitabine in the treatment of advanced oesophagogastric cancer? The REAL 2 trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2005;17:79-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, Lordick F, Ohtsu A, Omuro Y, Satoh T. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Talamonti MS, Kim SP, Yao KA, Wayne JD, Feinglass J, Bennett CL, Rao S. Surgical outcomes of patients with gastric carcinoma: the importance of primary tumor location and microvessel invasion. Surgery. 2003;134:720-77; discussion 720-77;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Powell J, McConkey CC. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia and adjacent sites. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:440-443. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Harrison LE, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Proximal gastric cancers resected via a transabdominal-only approach. Results and comparisons to distal adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Ann Surg. 1997;225:678-83; discussion 683-5. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Maehara Y, Watanabe A, Kakeji Y, Emi Y, Moriguchi S, Anai H, Sugimachi K. Prognosis for surgically treated gastric cancer patients is poorer for women than men in all patients under age 50. Br J Cancer. 1992;65:417-420. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Persiani R, D’Ugo D, Rausei S, Sermoneta D, Barone C, Pozzo C, Ricci R, La Torre G, Picciocchi A. Prognostic indicators in locally advanced gastric cancer (LAGC) treated with preoperative chemotherapy and D2-gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:227-36; discussion 237-8. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Harrison JD, Fielding JW. Prognostic factors for gastric cancer influencing clinical practice. World J Surg. 1995;19:496-500. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ding YB, Chen GY, Xia JG, Zang XW, Yang HY, Yang L, Liu YX. Correlation of tumor-positive ratio and number of perigastric lymph nodes with prognosis of patients with surgically-removed gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:182-185. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Siewert JR, Böttcher K, Roder JD, Busch R, Hermanek P, Meyer HJ. Prognostic relevance of systematic lymph node dissection in gastric carcinoma. German Gastric Carcinoma Study Group. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1015-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maruyama K. The most important prognostic factors cancer patients: a study using univariate and multivariate analyses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:63-68. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Kerkar SP, Kemp CD, Duffy A, Kammula US, Schrump DS, Kwong KF, Quezado M, Goldspiel BR, Venkatesan A, Berger A, Walker M, Toomey MA, Steinberg SM, Giaccone G, Rosenberg SA, Avital I. The GYMSSA trial: a prospective randomized trial comparing gastrectomy, metastasectomy plus systemic therapy versus systemic therapy alone. Trials. 2009;10:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Kemp CD, Kitano M, Kerkar S, Ripley RT, Marquardt JU, Schrump DS, Avital I. Pulmonary resection for metastatic gastric cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1796-1805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, Cohen MH, Douglass HO, Engstrom PF, Ezdinli EZ. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med. 1980;69:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1682] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ikeda Y, Oomori H, Koyanagi N, Mori M, Kamakura T, Minagawa S, Tateishi H, Sugimachi K. Prognostic value of combination assays for CEA and CA 19-9 in gastric cancer. Oncology. 1995;52:483-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Haglund C, Roberts PJ, Jalanko H, Kuusela P. Tumour markers CA 19-9 and CA 50 in digestive tract malignancies. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Koga T, Kano T, Souda K, Oka N, Inokuchi K. The clinical usefulness of preoperative CEA determination in gastric cancer. Jpn J Surg. 1987;17:342-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kunz PL, Gubens M, Fisher GA, Ford JM, Lichtensztajn DY, Clarke CA. Long-term survivors of gastric cancer: a California population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3507-3515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, Kleber G, Grothey A, Fleig WE. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2903-2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 895] [Article Influence: 47.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pinto C, Di Fabio F, Barone C, Siena S, Falcone A, Cascinu S, Rojas Llimpe FL, Stella G, Schinzari G, Artale S. Phase II study of cetuximab in combination with cisplatin and docetaxel in patients with untreated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (DOCETUX study). Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1261-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Iqbal S, Goldman B, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Lenz HJ, Zhang W, Danenberg KD, Shibata SI, Blanke CD. Southwest Oncology Group study S0413: a phase II trial of lapatinib (GW572016) as first-line therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2610-2615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wainberg ZA, Lin LS, DiCarlo B, Dao KM, Patel R, Park DJ, Wang HJ, Elashoff R, Ryba N, Hecht JR. Phase II trial of modified FOLFOX6 and erlotinib in patients with metastatic or advanced adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:760-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shah MA, Ramanathan RK, Ilson DH, Levnor A, D’Adamo D, O’Reilly E, Tse A, Trocola R, Schwartz L, Capanu M. Multicenter phase II study of irinotecan, cisplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5201-5206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Moehler M, Mueller A, Hartmann JT, Ebert MP, Al-Batran SE, Reimer P, Weihrauch M, Lordick F, Trarbach T, Biesterfeld S. An open-label, multicentre biomarker-oriented AIO phase II trial of sunitinib for patients with chemo-refractory advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1511-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Doi T, Muro K, Boku N, Yamada Y, Nishina T, Takiuchi H, Komatsu Y, Hamamoto Y, Ohno N, Fujita Y. Multicenter phase II study of everolimus in patients with previously treated metastatic gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1904-1910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |