Published online Mar 28, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1943

Revised: December 19, 2012

Accepted: January 5, 2013

Published online: March 28, 2013

Processing time: 246 Days and 5.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the impact of sociodemographic/clinical factors on early virological response (EVR) to peginterferon/ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) in clinical practice.

METHODS: We conducted a multicenter, cross-sectional, observational study in Hepatology Units of 91 Spanish hospitals. CHC patients treated with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin were included. EVR was defined as undetectable hepatitis C virus (HCV)-ribonucleic acid (RNA) or ≥ 2 log HCV-RNA decrease after 12 wk of treatment. A bivariate analysis of sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with EVR was carried out. Independent factors associated with an EVR were analyzed using a multiple regression analysis that included the following baseline demographic and clinical variables: age (≤ 40 years vs > 40 years), gender, race, educational level, marital status and family status, weight, alcohol and tobacco consumption, source of HCV infection, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) (≤ 85 IU/mL vs > 85 IU/mL), serum ferritin, serum HCV-RNA concentration (< 400 000 vs≥ 400 000), genotype (1/4 vs 3/4), cirrhotic status and ribavirin dose (800/1000/1200 mg/d).

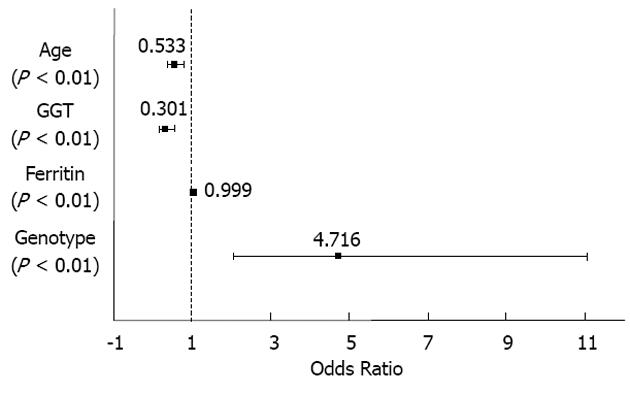

RESULTS: A total of 1014 patients were included in the study. Mean age of the patients was 44.3 ± 9.8 years, 70% were male, and 97% were Caucasian. The main sources of HCV infection were intravenous drug abuse (25%) and blood transfusion (23%). Seventy-eight percent were infected with HCV genotype 1/4 (68% had genotype 1) and 22% with genotypes 2/3. The HCV-RNA level was > 400 000 IU/mL in 74% of patients. The mean ALT and AST levels were 88.4 ± 69.7 IU/mL and 73.9 ± 64.4 IU/mL, respectively, and mean GGT level was 82 ± 91.6 IU/mL. The mean ferritin level was 266 ± 284.8 μg/L. Only 6.2% of patients presented with cirrhosis. All patients received 180 mg of peginterferon α-2a. The most frequently used ribavirin doses were 1000 mg/d (41%) and 1200 mg/d (41%). The planned treatment duration was 48 wk for 92% of patients with genotype 2/3 and 24 wk for 97% of those with genotype 1/4 (P < 0.001). Seven percent of patients experienced at least one reduction in ribavirin or peginterferon α-2a dose, respectively. Only 2% of patients required a dose reduction of both drugs. Treatment was continued until week 12 in 99% of patients. Treatment compliance was ≥ 80% in 98% of patients. EVR was achieved in 87% of cases (96% vs 83% of patients with genotype 2/3 and 1/4, respectively; P < 0.001). The bivariate analysis showed that patients who failed to achieve EVR were older (P < 0.005), had higher ALT (P < 0.05), AST (P < 0.05), GGT (P < 0.001) and ferritin levels (P < 0.001), a diagnosis of cirrhosis (P < 0.001), and a higher baseline viral load (P < 0.05) than patients reaching an EVR. Age < 40 years [odds ratios (OR): 0.543, 95%CI: 0.373-0.790, P < 0.01], GGT < 85 IU/mL (OR: 3.301, 95%CI: 0.192-0.471, P < 0.001), low ferritin levels (OR: 0.999, 95%CI: 0.998-0.999, P < 0.01) and genotype other than 1/4 (OR: 4.716, 95%CI: 2.010-11.063, P < 0.001) were identified as independent predictors for EVR in the multivariate analysis.

CONCLUSION: CHC patients treated with peginterferon-α-2a/ribavirin in clinical practice show high EVR. Older age, genotype 1/4, and high GGT were associated with lack of EVR.

- Citation: García-Samaniego J, Romero M, Granados R, Alemán R, Jorge Juan M, Suárez D, Pérez R, Castellano G, González-Portela C. Factors associated with early virological response to peginterferon-α-2a/ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(12): 1943-1952

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i12/1943.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1943

Until recent approval of the first direct acting antivirals (DAAs) against hepatitis C virus (HCV)[1-4], the combination of pegylated interferon and ribavirin was the standard of care (SOC) for chronic hepatitis C (CHC)[5-8] with the goal of achieving a sustained viral response (SVR) [undetectable hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid (HCV-RNA) at week 24]. However, the overall SVR rate with standard peginterferon and ribavirin combination does not exceed 56%-63%[5,9,10], and is even lower in some patient subgroups[10]. Indeed, pivotal studies showed that HCV genotype 1 patients achieve a SVR rate of 41%-56%, whereas in those infected with HCV genotype 2/3, a SVR is obtained in 74%-80%[5,9-11]. Variability in virological response depends on diverse patient factors as well as virological and histological factors. Genotype other than 1, low baseline viral load, age less than 40 years, body weight ≤ 75 kg and absence of advanced fibrosis and/or cirrhosis have been identified as predictive factors of SVR in the studies evaluating peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin combination[9,12].

Pivotal studies have shown that early virological response (EVR) is highly predictive of SVR[9,13]. Accordingly, patients who do not achieve an EVR have an almost null probability of achieving a SVR[9,13-15]. The study conducted by Fried et al[9] showed that only 3% of patients who did not obtain an EVR with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin achieved a SVR. The high negative predictive value (PPV) of EVR has great clinical value as it allows us to decide whether to continue or discontinue treatment at week 12, therefore preventing or minimizing the adverse effects related to treatment continuation. Current treatment guidelines for hepatitis C include this decision criteria at week 12[5,7,8,16] and recommend discontinuation of treatment in patients who fail to achieve an EVR. In addition, the clinical utility of EVR has been demonstrated in the routine clinical practice setting, particularly in genotype 1-infected patients[17].

Limited data have been reported regarding the EVR predictive factors in patients receiving peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin combination therapy. Correct identification of these factors could be a useful strategy to optimize treatment in CHC and improve SVR rates, particularly in patients with genotype 1. On the other hand, treatment adherence is key to achieve successful treatment. The occurrence of adverse effects associated with peginterferon and/or ribavirin is the main reason for dose reduction or treatment discontinuation. As a result, 15%-20% of patients participating in clinical trials and approximately 25% of those in routine clinical practice discontinue treatment[18]. Lack of adherence during the first 12 wk of treatment has been shown to have a particularly negative impact on EVR[13,19]. Thus, the PPV of EVR associated with good treatment compliance is very high, achieving a SVR in 75% of cases with EVR and good treatment adherence[9].

Given that sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with EVR are not well known and considering that treatment adherence is a variable closely related to EVR, characterization of viral and patient factors associated with treatment compliance, and hence EVR, has important clinical implications. The present study was designed to analyze baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with EVR and antiviral treatment compliance in CHC patients treated with peginterferon α-2a in the routine clinical practice setting in Spain.

This was a national, multicenter, cross-sectional, observational study. The study was carried out in the Hepatology Units of 91 Spanish hospitals. All participating patients gave their written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Carlos III of Madrid. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and their amendments.

The study included adult patients (over 18 years of age) diagnosed with CHC and treated with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin under routine clinical practice conditions. Patients with any contraindication to hepatitis C treatment according to the prescribing information and those with HBV and/or human immunodeficiency virus coinfection were excluded.

The main purpose of the study was to analyze EVR in relation to sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. For this purpose, the following variables were recorded at the start of treatment: age, sex, race, nationality, educational level, marital status, occupation and family status, weight, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, source of HCV infection, methadone replacement therapy, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and ferritin levels, cirrhotic status, viremia and HCV genotype. In addition, ribavirin dose and scheduled duration of treatment, dose reductions of peginterferon α-2a and/or ribavirin up to week 12, data on premature treatment discontinuation (week and reason for discontinuation) were also collected. Furthermore, data on HCV-RNA concentrations at week 12 were recorded and EVR was analyzed (complete/partial). HCV-RNA levels were measured using quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays, mostly the Amplicor HCV Monitor (Roche, Kenilworth NJ, United States), although other commercial tests were used in some centers. A lower limit of detection of 50 IU/mL was considered in all participating hospitals. The secondary objective of the study was to evaluate treatment adherence at week 12.

EVR was defined as undetectable levels of HCV-RNA at week 12 (complete EVR) or ≥ 2 log reduction in HCV viral load from baseline (partial EVR).

To evaluate treatment adherence, compliance was recorded according to the 80/80/80 rule[20] and modified according to the study design. Treatment compliant or adherent patients were those receiving 80% or more of the total dose of peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin during 80% of the time until week 12. Likewise, noncompliant patients included those who received < 80% of the prescribed dose of one or both drugs during < 80% of the expected duration (12 wk).

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed on the sociodemographic and clinical variables collected from the medical records at the start of treatment with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin. Quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean, median, SD, minimum, maximum, first quartile and third quartile) and the results are expressed as mean ± SD or median (range). Qualitative variables are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. To characterize the population based on patient sex and the influence of sociodemographic and clinical characteristic on EVR, a bivariate analysis was carried out using Student’s t test for quantitative variables and the chi-square test for the remaining sociodemographic and clinical qualitative independent variables. Similarly, a bivariate analysis of sociodemographic and clinical variables associated with EVR was carried out based on patient race. Variables with statistical significance or with P < 0.10 in the bivariate model were analyzed in a multivariate logistic regression model. Some factors that were not statistically significant were retained in the model based on previous clinical evidence. Odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI were calculated for the independent predictive factors of EVR. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, only patients with available data for all the variables taken into account for the analysis were included. Significance level was set at P < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States).

Baseline patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. A total of 1202 patients were included in the study. Thirty-six were excluded as they met at least one of the following criteria: peginterferon dose other than 180 mg (30 patients), negative HCV-RNA at baseline visit (1 patient), HCV-RNA level not available at week 12 when withdrawal had not occurred (8 patients). The number of evaluable patients was 1166, of which 1014 were analyzed and 152 were excluded for having a detectable viral load at week 12 without specifying the value and/or detection level.

| Characteristics | |

| Patient sociodemographics | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 712 (70) |

| Female | 302 (30) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 44.3 ± 9.8 |

| Nationality | |

| Spanish | 919 (91) |

| Other | 93 (9) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 980 (97) |

| Other | 27 (3) |

| Educational level | |

| Did not complete compulsory education | 125 (12) |

| Compulsory education | 506 (50) |

| Professional training | 243 (24) |

| University | 131 (13) |

| Postgraduate/Master/PhD | 7 (1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 280 (28) |

| Married | 580 (58) |

| Separated | 138 (14) |

| Widowed | 11 (1) |

| Family status | |

| Lives with another person | 898 (89) |

| Lives alone | 97 (10) |

| Prison inmate | 16 (2) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 75.7 ± 13.4 |

| Alcohol consumption | 154 (15) |

| Tobacco consumption | 514 (51) |

| Source of HCV infection1 | |

| IVDU | 256 (25) |

| Transfusion | 234 (23) |

| Other | 55 (6) |

| Unknown | 462 (46) |

| Methadone replacement therapy | 65 (7) |

| ALT (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 88.4 ± 69.7 |

| AST (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 73.9 ± 64.4 |

| GGT (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 82.0 ± 91.6 |

| Ferritin (μg/L), mean ± SD | 266.0 ± 284.8 |

| Cirrhosis | 62 (6.2) |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1/4 | 784 (78) |

| 2/3 | 223 (22) |

| HCV-RNA | |

| < 400 000 IU/mL | 264 (26) |

| ≥ 400 000 IU/mL | 744 (73) |

Seven hundred and twelve (70%) patients were male. The vast majority of patients were Spanish (91%) and Caucasian (97%). Fifty percent of patients had completed compulsory education. Of the total number of patients, 580 (57%) were married and 898 (89%) patients lived with another person (Table 1).

The mean age was 43.3 ± 9.0 years in men and 46.6 ± 11.4 years in women (P < 0.001). No differences were found in race, educational level or family status based on gender. No significant differences were found in baseline sociodemographic characteristics based on race. The only differences noted were a greater proportion of women over 40 who were Caucasian (P < 0.005) and a higher educational level among Caucasian patients (P < 0.01).

Alcohol consumption was reported in 154 (15%) patients and 514 (51%) were smokers. The most common source of HCV infection was intravenous drug use (25%) followed by transfusion (23%). Mean ALT and AST levels were 88.4 ± 69.7 and 73.9 ± 64.4 IU/mL, respectively, and the mean GGT level was 82 ± 91.6 IU/mL. The mean ferritin level was 266 ± 284.8 μg/L. Only 62 (6.2%) patients presented with cirrhosis.

Of the total number of patients, 784 (78%) had genotype 1/4, of which 694 (68%) had genotype 1. The HCV-RNA level was greater than 400 000 IU/mL in 744 (73.8%) patients (Table 1). The proportion of patients with tobacco and alcohol consumption habit was greater in men (P < 0.001). The diagnosis of cirrhosis was also more common in men (P < 0.05). Intravenous drug abuse as the source of HCV infection was more frequent in men and transfusion was more frequent in women (P < 0.001). Among the clinical variables analyzed, there were no differences in baseline viral load level or HCV genotype according to gender, but men had higher ALT, AST and GGT values (P < 0.001) and higher levels of ferritin (P < 0.001). With regard to ribavirin dose, 800 mg/d and 1000 mg/d were the most common doses given to women, whereas men received the 1200 mg/d dose more frequently (P < 0.001).

All patients received 180 μg of peginterferon α-2a. The most frequently used ribavirin doses were 1000 mg/d (41%) and 1200 mg/d (41%) (Table 2). In accordance with current treatment recommendations, the 1000 mg/d and 1200 mg/d doses of ribavirin were used more often for patients with genotype 1/4 (49% and 45% of patients received doses of 1200 and 1000 mg/d, respectively), whereas more than half of those with genotype 2/3 (58%) received 800 mg/d of ribavirin (P < 0.001).

| Treatment data | |

| Peginterferon α-2a | |

| Dose: 180 mg | 1014 (100) |

| At least one dose reduction of peginterferon | 66 (7)1 |

| At least one discontinuation of peginterferon | 46 (81) |

| Ribavirin | |

| Dose | |

| 800 mg/d | 183 (18) |

| 1000 mg/d | 413 (41) |

| 1200 mg/d | 416 (41) |

| 1400 mg/d | 1 (0.1) |

| At least one dose reduction of ribavirin | 66 (7)1 |

| At least one discontinuation of ribavirin | 56 (89) |

| Scheduled treatment duration | |

| 24 wk | 234 (23) |

| 48 wk | 773 (77) |

In more than three-quarters of patients, the scheduled duration of treatment was 48 wk (Table 2). For 97% of patients with genotype 1/4, the planned treatment duration was 48 wk and in 92% of those with genotype 2/3 the scheduled duration was 24 wk (P < 0.001).

Sixty-six (7%) patients had their peginterferon α-2a dose reduced on at least one occasion. Of these, 46 (81%) patients had only one dose reduction. Similarly, 66 (7%) patients experienced at least one dose reduction of ribavirin. Of these, 56 (89%) patients had at least one dose reduction before week 12. Only 15 (2%) patients required a dose reduction of both drugs (Table 2).

Of 1014 patients included in the analysis, 866 (87%) achieved an EVR. Of these patients, 699 (70%) had a complete EVR and 176 (18%) achieved a partial EVR. The results showed significant differences in EVR depending on genotype, and the percentage of patients with EVR at week 12 was higher in the group of patients with genotype 2/3 (96% vs 83% of patients with genotype 2/3 and genotype 1/4, respectively; P < 0.001).

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the early responders (EVR) and non-responders (non-EVR). According to the results obtained from the bivariate analysis, the only sociodemographic variable associated with EVR was age (P < 0.005). The clinical variables associated with EVR were ALT (P < 0.005), AST (P < 0.05) and GGT values (P < 0.001), ferritin levels (P < 0.001), presence of cirrhosis (P < 0.001), viral genotype (P < 0.001), and baseline viral load (P < 0.05).

| Factors | EVR | Non-EVR | P value1 |

| Patient sociodemographics | |||

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 43.9 ± 9.7 | 47.0 ± 10.0 | < 0.005 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 602 (86) | 101 (14) | NS |

| Female | 264 (89) | 33 (11) | |

| Origin | |||

| Developed country | 64 (93) | 5 (7) | NS |

| Developing country | 801 (86) | 129 (14) | |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 836 (87) | 130 (14) | NS |

| Other | 24 (89) | 3 (11) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Equivalent to or less than high | 537 (86) | 85 (14) | NS |

| Professional training | 209 (87) | 31 (13) | |

| University or higher | 119 (88) | 17 (13) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 235 (85) | 41 (15) | NS |

| Married | 491 (86) | 81 (14) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 135 (92) | 12 (8) | |

| Family status | |||

| Lives alone | 82 (85) | 15 (16) | NS |

| Lives with another person | 769 (87) | 117 (13) | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 75.6 ± 13.4 | 77.2 ± 13.5 | NS |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 731 (86) | 115 (14) | NS |

| Yes | 133 (88) | 19 (13) | |

| Tobacco consumption | |||

| No | 414 (85) | 75 (15) | NS |

| Yes | 450 (88) | 59 (12) | |

| Source of HCV infection | |||

| Injection drug use | 221 (90) | 26 (11) | NS |

| Transfusion | 126 (89) | 16 (11) | |

| IV route | 79 (87) | 12 (13) | |

| Other | 435 (85) | 78 (15) | |

| Methadone replacement therapy | |||

| No | 803 (86) | 126 (14) | NS |

| Yes | 57 (89) | 7 (11) | |

| ALT (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 86.3 ± 69.4 | 101.7 ± 71.5 | < 0.05 |

| AST (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 72.1 ± 65.3 | 84.8 ± 58.5 | < 0.05 |

| GGT (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 73.6 ± 85.2 | 134.0 ± 114.4 | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (μg/L), mean ± SD | 248.0 ± 268.8 | 388.8 ± 357.3 | < 0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | |||

| No | 817 (88) | 112 (12) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 41 (67) | 20 (33) | |

| HCV genotype | |||

| 1/4 | 645 (84) | 126 (16) | < 0.001 |

| 2/3 | 214 (96) | 8 (4) | |

| HCV-RNA (IU/mL), mean ± SD | 3 354 135.6 ± 5 978 359.9 | 3 781 940.0 ± 4 780 000.6 | NS |

| Baseline viral load | |||

| < 400 000 IU/mL | 237 (91) | 25 (10) | < 0.05 |

| ≥ 400 000 IU/mL | 623 (85) | 109 (15) | |

In the multivariate analysis, the only sociodemographic factor identified as a predictor of EVR was age (OR: 0.543, 95%CI: 0.373-0.790, P < 0.01) and the clinical factors predictive of EVR were GGT level (OR: 3.301, 95%CI: 0.192-0.471, P < 0.001), ferritin level (OR: 0.999, 95%CI: 0.998-0.999, P < 0.01) and genotype (OR: 4.716, 95%CI: 2.010-11.063, P < 0.001). Age ≤ 40 years, GGT level ≤ 85 IU/mL, low ferritin levels and HCV genotype other than 1/4 were independent predictors of EVR (Figure 1).

Treatment compliance was greater than 80% in 971 (97.8%) patients. No significant differences were found between patients with treatment adherence greater than 80% and those whose compliance was less than 80% with regard to their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (data not shown).

The response to treatment with peginterferon plus ribavirin is heterogeneous and non-optimal in several HCV patients, as occurs in those infected with genotype 1, high viral load, advanced fibrosis, metabolic syndrome or non-CC polymorphisms of the interleukin 28b gene (IL28b)[12,13,15,21,22].

EVR is highly predictive of SVR[9,23] and provides hepatologists with a valuable tool to decide on continuation and duration of treatment, as well as providing patients with an additional motivation to adhere to treatment. The predictive value of EVR in patients infected with genotype 1 in the clinical practice setting in Spain[17] was previously shown to be comparable to that obtained in pivotal trials[9,23]. However, although identification of both viral and host factors associated with EVR may be very useful to predict SVR and therefore guide therapy[13], to date, there are limited data available addressing this issue.

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest series from a clinical setting to analyze factors associated with EVR in CHC patients treated with peginterferon plus ribavirin under routine clinical practice conditions. The data analysis showed that 87% of patients achieved EVR. This response rate is comparable or even higher than that reported in international pivotal trials with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin[9,23] and confirm the results reported in previous studies conducted in Spain, also under routine clinical practice conditions, but with a considerably lower number of patients[17,24]. A complete EVR was observed in 70% of our patients and again this rate was higher than that reported in other previous studies, which ranged from 34% to 64%[9,10,12,25,26].

As expected, the percentage of patients with EVR was higher in the group of patients with genotype 2/3 than in those with genotype 1/4 according to previous studies[9,10,27-29]. However, despite including a high percentage of patients with genotype 1 (the most difficult to cure), our study achieved response rates as high as those in the pivotal trials.

Patients who failed to achieve EVR were older, had higher ALT, AST, GGT and ferritin levels, a more frequent diagnosis of cirrhosis and a higher baseline viral load than patients achieving EVR. Most of the limited available studies on factors associated with EVR have shown that low baseline viral load, younger age, absence of overweight/obesity and lack of cirrhosis are independent factors associated with EVR[30-33]. In our study, age < 40 years, GGT levels < 85 IU/mL, low ferritin levels and genotype non-1/4 were identified as independent predictive factors of EVR in the multivariate analysis.

Interestingly, a recent study has identified high GGT as a predictor of nonresponse to treatment with peginterferon in patients infected with genotype 1[34]. The precise mechanism whereby increased GGT levels may affect treatment response in CHC remains a matter of debate, although it may be related either to a more intense degree of necroinflammatory activity, more advanced fibrosis, or to hepatic steatosis[35,36]. In this regard, a positive correlation between serum GGT levels and the hepatic expression of proinflammatory tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) mRNA in CHC has been suggested[37]. Indeed, hepatic levels of TNF-α mRNA have been found to be significantly higher in nonresponders to IFN-α-based therapy than in those with a SVR. On the other hand, although the multivariate analysis identified high levels of ferritin as an independent predictor of EVR, this association was clearly irrelevant (OR = 0.999). Therefore, ferritin level may lack clinical validity as a predictive factor of EVR in this setting.

Age was found to be an independent factor for EVR in our study, in agreement with previous series where it was shown that age greater than 40 years is an independent predictor of nonresponse to treatment[12,29,34]. Furthermore, older patients have been suggested to be more resistant to peginterferon-based therapies since they are more frequently infected by HCV genotype 1b, have a longer disease duration and exhibit greater liver damage than younger patients.

Consistent with most published studies[10,12,17,38], our findings show that the proportion of women with CHC treated with peginterferon plus ribavirin in routine practice in Spain is much lower in comparison to the proportion of men, in the absence of demographic variables justifying this difference, or known barriers of access to treatment for women. In addition, women are treated at an older age than men. We can speculate that the lower fibrosis severity as well as the higher rate of normal ALT levels in women with CHC can explain the relatively low proportion of female patients treated in our series. Although in some studies women have shown higher response rates than men[31,38], our data did not show differences in EVR based on gender despite the high proportion of male patients. In light of these results, new epidemiological studies on the prevalence of HCV infection, as well as clinical studies including a larger number of women are needed to determine if there is gender inequality in the prescription of antiviral therapy.

Baseline HCV viral load is a well-known independent predictive factor of treatment response[12,29-31,33]. In agreement with previous evidence, the patients in our study who achieved EVR were those who had lower baseline viral loads (< 400 000 IU/mL), although viral load did not constitute a predictive factor for EVR in the multiple logistic regression analysis.

Race has been identified as a predictive factor of EVR in previous studies[12]. The data from our study, despite its large sample size, does not allow us to conclude that race plays a role in EVR because the vast majority of patients included in the study were Caucasian (97.3%). Furthermore, when the study was designed, genetic analysis of IL28b gene polymorphisms, which are related to race[21], was not available. Indeed, one limitation of our study is the lack of information on IL-28B genotype as it has been described as a relevant predictor of treatment response[39,40]. However, the impact of the imbalance of this genetic polymorphism between groups on treatment response was described just after the data from this study were collected.

Our study also revealed that Spanish CHC patients treated in routine clinical practice receive the correct doses of each drug according to current treatment guidelines, and this is critical since both dose optimization and treatment duration are essential to maximize response[17]. The treatment regimen is individualized, according to current guideline recommendations, based on the viral genotype, so that patients with genotype 1/4 are treated with ribavirin in weight-adjusted doses of 1000-1200 mg/d for 48 wk, whereas patients carrying genotypes 2/3 are treated in most cases with ribavirin at a dose of 800 mg/d for 24 wk.

Combination therapy frequently causes adverse effects. Most are mild and controlled by reducing the dose of each drug or with additional treatments including growth factors, but in some cases they require discontinuation of treatment. Various studies have shown that dose reductions and particularly treatment discontinuation are associated with a marked reduction in the EVR rate[20]. Other reports have noted that dose reductions of peginterferon and/or ribavirin are quite frequent during the first 12 wk of treatment[13]. However, in the current analysis, only 7% of patients required dose reduction of peginterferon or ribavirin. Moreover, it should be noted that only 7 patients of the total population analyzed discontinued treatment due to serious adverse effects in the first 12 wk. This percentage (less than 1%) is markedly lower than that reported in other studies[11,41].

Treatment compliance is a variable closely related to EVR[13,19,20]. It has been shown that lack of adherence during the first 12 wk of treatment has a negative impact on EVR. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients who met the 80/80/80 rule have a greater response than those receiving lower doses or for less time[20]. In our series, 98% of patients met the 80/80/80 rule up to week 12. Good treatment compliance is one of the factors explaining the high rate of EVR seen in our study. Treatment modifications and the motivation of patients may have had a significant impact on adherence to treatment. The low dose reductions required for both drugs could have encouraged patients to complete the prescribed course of treatment. Additionally, determination of EVR provides patients and physicians with an early goal and motivates them to adhere to treatment recommendations. Moreover, it is noteworthy that patients were treated by hepatologists belonging to units with wide experience in the care of CHC patients.

The main limitations of this study arise from the occurrence of the major advance in CHC in the last years, the development of DAAs and the recent approval of the triple therapy as the new SOC for CHC. Nevertheless, despite the obvious change in treatment paradigm, therapy based on peginterferon plus ribavirin will continue to play an important role as SOC, especially for non-1 HCV patients, considering that protease inhibitors must be combined with peginterferon plus ribavirin in genotype 1 patients. In addition, while remarkably effective, the recently approved protease inhibitors are also accompanied by frequent serious toxicities and considerable costs. Therefore, some patients who cannot tolerate protease inhibitors will need to be treated with dual combination given that triple combination regimens have a higher side effect burden[3,42,43]. Additionally, the high cost of the DAAs will probably preclude the use of triple-combination therapies in health care systems constrained by rising costs and economically disadvantaged regions. It is well known that patients with rapid virological response to dual combination achieve SVR in higher rates, close to 90%, and therefore, despite the above limitations, our findings may be relevant and applicable at the onset of the DAAs era. Furthermore, our findings provide a meaningful assessment of factors associated with EVR regarding applicability to guide therapy of real-world patients given that our study population comprises a larger, more representative cohort of patients than those included in clinical trials evaluating predictive factors of EVR. However, further studies will be needed to validate whether the predictive factors of EVR to dual therapy remain a predictive tool in the context of new DAA agents in the routine clinical practice setting.

In summary, CHC patients treated with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin in routine clinical practice in Spain have high EVR rates, similar to those obtained in pivotal studies, and a high level of treatment compliance. Age > 40 years, genotype 1/4 and GGT ≥ 85 IU/mL were independent predictive factors of lack of EVR. In the new era of hepatitis C treatment where standard treatment is incorporated with DAAs, identification of predictive factors such as the new definitions of extended rapid viral response will be an essential tool to achieve maximum response rates.

Editorial and medical writing assistance was provided by Cristina Vidal and Antonio Torres from Dynamic Science. The authors would like to acknowledge the investigators and collaborators of MONOTRANS Study Group: Pérez R, Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain; Muñoz R, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Manzano M, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Fernández I, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Domínguez F, Clínica Santa Cristina, Vigo, Spain; Fajardo JM, Hospital Infanta Elena, Huelva, Spain; Pastor E, Hospital Arquitecto Marcide, Ferrol, Spain; Suárez I, Hospital Hospital Infanta Elena, Huelva, Spain; Morano LE, Hospital Meixoeiro, Vigo, Spain; Espinosa MD, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain; Sansó A, Hospital de Manacor, Mallorca, Spain; Montoliú S, Hospital Joan XXIII, Tarragona, Spain; Pardo A, Hospital Joan XXIII, Tarragona, Spain; Sánchez J, Hospital Río Carrión, Palencia, Spain; Amine S, Hospital General de Lanzarote, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Alonso MM, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain; Eraña L, Hospital Santiago Apóstol, Vitoria, Spain; Guerrero J, Hospital Cruz Roja del INGESA, Ceuta, Spain; García E, Hospital General de Fuerteventura, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Sánchez JJ, Virgen de la Salud, Toledo, Spain; Calvo S, Hospital Comarcal de El Escorial, Madrid, Spain; Vázquez E, Complejo Hospitalario Pontevedra, Pontevedra, Spain; Moreno D, Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid, Spain; González R, Hospital de Móstoles, Madrid, Spain; Morán S, Hospital Santa María del Rosell, Cartagena, Spain; Torrente V, Hospital Sant Joan de Reus, Tarragona, Spain; Jiménez E, Hospital Universitario Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Lee C, Hospital Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Hervias D, Hospital Virgen de Altagracia-Manzanares, Ciudad Real, Madrid, Spain; Rincón JP, Santa María del Rosell, Cartagena, Spain; Gimenez A, Hospital General de Granollers, Barcelona, Spain; Rodriguez R, Complejo Hospitalario Santa María Madre, Orense, Spain; Moreno M, Hospital General de Fuerteventura, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; Casanova C, Hospital Universitario de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain; Sánchez H, Hospital La Inmaculada, Almeria, Spain; Juan Carlos Penalva, Hospital de Torrevieja, Alicante, Spain; Compañy L, Hospital General de Alicante, Alicante, Spain; Sáez J, Hospital de Elche, Alicante, Spain.

Peginterferon plus ribavirin is the standard therapy for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) world-wide. Early virological response (EVR) predicts sustained virological response (SVR) in CHC. Although identification of both viral and host factors associated with EVR may be very useful to predict SVR and therefore guide therapy, to date, there are limited data available addressing this issue in clinical practice.

The high negative predictive value of EVR has remarkable value in clinical practice since it allows to decide whether to continue or discontinue treatment at week 12, therefore preventing or minimizing the adverse effects related to treatment continuation. Indeed, current treatment guidelines for hepatitis CHC include this decision criterion and recommend discontinuing treatment in patients who fail to achieve an EVR.

The present study is the largest series from a clinical setting to analyze predictive factors of EVR in CHC patients treated with peginterferon α-2a plus ribavirin in routine clinical practice. The remarkably high EVR rates obtained in our study were similar to those reported with this dual therapy in pivotal studies, and confirm the data from previous studies in clinical practice in Spain which included a significantly lower number of patients. Age > 40 years, genotype 1/4 and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) ≥ 85 IU/mL were identified as independent predictive factors of lack of EVR.

The results from this study may be useful in guiding treatment decision making. In particular, early prediction of virological response to dual therapy can help to identify candidates who are unlikely to have a SVR before treatment initiation or in the early treatment phase.

EVR indicates EVR which is defined as undetectable hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid (HCV-RNA) or ≥ 2 log decrease in HCV-RNA after 12 wk of treatment.

This study is well constructed and it is based in a big CHC patient cohort coming from 91 hospitals through all Spanish territory. This is an interesting and relevant study which confirms the results of previous studies with a notably lower number of Spanish cases. Moreover, this study consolidates some basal factors such a GGT levels, age or viral genotype as predictive factors of EVR. This study also highlights the higher rate of ERV in Spain compared with other regions.

P- Reviewer Rodriguez-Frias F S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yan JL

| 1. | Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 1307] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci P, Flisiak R. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1905] [Cited by in RCA: 1854] [Article Influence: 132.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Pound D, Davis MN, Galati JS, Gordon SC, Ravendhran N. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:705-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, Focaccia R, Younossi Z, Foster GR, Horban A. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1230] [Cited by in RCA: 1199] [Article Influence: 85.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002--June 10-12, 2002. Hepatology. 2002;36:S3-S20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cammà C, Licata A, Cabibbo G, Latteri F, Craxì A. Treatment of hepatitis C: critical appraisal of the evidence. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:399-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dienstag JL, McHutchison JG. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:225-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147-1171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4747] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H, Bernstein D, Rizzetto M. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346-355. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, Chung RT, Hamzeh FM, Jensen DM. Factors associated with rapid and early virologic response to peginterferon alfa-2a/ribavirin treatment in HCV genotype 1 patients representative of the general chronic hepatitis C population. J Viral Hepat. 2010;17:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Davis GL, Wong JB, McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Harvey J, Albrecht J. Early virologic response to treatment with peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:645-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Husa P, Oltman M, Ivanovski L, Rehák V, Messinger D, Tietz A, Urbanek P. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon α-2a (40 kD) plus ribavirin among patients with chronic hepatitis C and earlier treatment failure to interferon and ribavirin: an open-label study in central and Eastern Europe. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee SS, Heathcote EJ, Reddy KR, Zeuzem S, Fried MW, Wright TL, Pockros PJ, Häussinger D, Smith CI, Lin A. Prognostic factors and early predictability of sustained viral response with peginterferon alfa-2a (40KD). J Hepatol. 2002;37:500-506. [PubMed] |

| 16. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2011;55:245-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 889] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 65.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Diago M, Olveira A, Solá R, Romero-Gómez M, Moreno-Otero R, Pérez R, Salmerón J, Enríquez J, Planas R, Gavilán JC. Treatment of chronic he1patitis C genotype 1 with peginterferon-alpha2a (40 kDa) plus ribavirin under routine clinical practice in Spain: early prediction of sustained virological response rate. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cacoub P, Ouzan D, Melin P, Lang JP, Rotily M, Fontanges T, Varastet M, Chousterman M, Marcellin P. Patient education improves adherence to peg-interferon and ribavirin in chronic genotype 2 or 3 hepatitis C virus infection: a prospective, real-life, observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6195-6203. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Manns MP. Adherence to combination therapy: influence on sustained virologic response and economic impact. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:S11-S24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2776] [Cited by in RCA: 2721] [Article Influence: 170.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zeuzem S. Heterogeneous virologic response rates to interferon-based therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: who responds less well? Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:370-381. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Ferenci P, Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Smith CI, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Predicting sustained virological responses in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40 KD)/ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2005;43:425-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 409] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tural C, Galeras JA, Planas R, Coll S, Sirera G, Giménez D, Salas A, Rey-Joly C, Cirera I, Márquez C. Differences in virological response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin between hepatitis C virus (HCV)-monoinfected and HCV-HIV-coinfected patients. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:1047-1055. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Di Bisceglie AM, Ghalib RH, Hamzeh FM, Rustgi VK. Early virologic response after peginterferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin or peginterferon alpha-2b plus ribavirin treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:721-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jeffers LJ, Cassidy W, Howell CD, Hu S, Reddy KR. Peginterferon alfa-2a (40 kd) and ribavirin for black American patients with chronic HCV genotype 1. Hepatology. 2004;39:1702-1708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Heintges T, Shiffman ML, Gordon SC, Hoefs JC, Schiff ER, Goodman ZD, Laughlin M, Yao R. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing pegylated interferon alfa-2b to interferon alfa-2b as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2001;34:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 468] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, Niederau C, Minuk GS, Ideo G, Bain V, Heathcote J, Zeuzem S, Trepo C. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT). Lancet. 1998;352:1426-1432. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Rasenack J, Heathcote EJ, Lai MY, Gane E, O’Grady J, Reichen J, Diago M, Lin A. Peginterferon alfa-2a in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1666-1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 883] [Cited by in RCA: 850] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ferenci P, Laferl H, Scherzer TM, Gschwantler M, Maieron A, Brunner H, Stauber R, Bischof M, Bauer B, Datz C. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for 24 weeks in hepatitis C type 1 and 4 patients with rapid virological response. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:451-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jensen DM, Morgan TR, Marcellin P, Pockros PJ, Reddy KR, Hadziyannis SJ, Ferenci P, Ackrill AM, Willems B. Early identification of HCV genotype 1 patients responding to 24 weeks peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kd)/ribavirin therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:954-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mangia A, Minerva N, Bacca D, Cozzolongo R, Ricci GL, Carretta V, Vinelli F, Scotto G, Montalto G, Romano M. Individualized treatment duration for hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:43-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang JF, Chiu CF, Yang YH, Hou NJ, Lee LP, Hsieh MY, Lin ZY, Chen SC. Rapid virological response and treatment duration for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2008;47:1884-1893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Weich V, Herrmann E, Chung TL, Sarrazin C, Hinrichsen H, Buggisch P, Gerlach T, Klinker H, Spengler U, Bergk A. The determination of GGT is the most reliable predictor of nonresponsiveness to interferon-alpha based therapy in HCV type-1 infection. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1427-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hwang SJ, Luo JC, Chu CW, Lai CR, Lu CL, Tsay SH, Wu JC, Chang FY, Lee SD. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: prevalence and clinical correlation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:190-195. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Silva IS, Ferraz ML, Perez RM, Lanzoni VP, Figueiredo VM, Silva AE. Role of gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:314-318. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Taliani G, Badolato MC, Nigro G, Biasin M, Boddi V, Pasquazzi C, Clerici M. Serum concentration of gammaGT is a surrogate marker of hepatic TNF-alpha mRNA expression in chronic hepatitis C. Clin Immunol. 2002;105:279-285. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Bressler BL, Guindi M, Tomlinson G, Heathcote J. High body mass index is an independent risk factor for nonresponse to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:639-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Iadonato SP, Katze MG. Genomics: Hepatitis C virus gets personal. Nature. 2009;461:357-358. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell E. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1505] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 93.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Jacobson IM, Brown RS, Freilich B, Afdhal N, Kwo PY, Santoro J, Becker S, Wakil AE, Pound D, Godofsky E. Peginterferon alfa-2b and weight-based or flat-dose ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2007;46:971-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hézode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci P, Pol S, Goeser T, Bronowicki JP, Bourlière M, Gharakhanian S, Bengtsson L. Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1839-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, McNair L, Alam J, Muir AJ. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1827-1838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 851] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |