Published online Jan 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.103

Revised: September 19, 2012

Accepted: September 22, 2012

Published online: January 7, 2013

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of a single-use endoscopy as an alternative procedure to nasogastric lavage in patients with acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

METHODS: Patients who presented with hematemesis, melena or hematochezia were enrolled in this study. EG scan™ and conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were subsequently performed. Active bleeding was defined as blood in the stomach, and inactive bleeding was defined as coffee ground clots and clear fluid in the stomach. The findings were recorded and compared.

RESULTS: Between January and March, 2011, 13 patients that presented with hematemesis (n = 4), melena (n = 6), or bleeding from a previous nasogastric feeding tube (n = 3), were enrolled in this study. In 12 patients with upper GI bleeding, the EG scan device revealed that 7 patients had active bleeding and 5 patients had inactive bleeding, whereas conventional EGD revealed that 8 patients had active bleeding and 4 patients had inactive bleeding. The sensitivity and specificity of the EG scan device was 87.5% and 100% for active bleeding, with conventional EGD serving as a reference. No complication were reported during the EG scan procedures.

CONCLUSION: The EG scan is a feasible device for screening acute upper GI bleeding. It may replace nasogastric lavage for the evaluation of acute upper GI bleeding.

- Citation: Cho JH, Kim HM, Lee S, Kim YJ, Han KJ, Cho HG, Song SY. A pilot study of single-use endoscopy in screening acute gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(1): 103-107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i1/103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i1.103

Acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is managed by early conventional endoscopy within 24 h of presentation[1-3]. In high-risk upper GI bleeding, urgent endoscopy reduces mortality; therefore, risk stratification is important[4,5]. Nasogastric lavage is a routine procedure used to evaluate acute upper GI bleeding and to assess risk before performing conventional endoscopy. The findings of nasogastric lavage help doctors decide whether to perform an early conventional endoscopy[1,6-8]. However, the effect of nasogastric lavage on clinical outcomes and mortality remains controversial[3,9-12]. Nasogastric intubation and lavage is one of the most painful procedures performed in the emergency department[13,14].

A novel single-use endoscopy device (EG scan™: IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) has been developed from the MiroCam® capsule endoscopy technology created by the IntroMedic company and Professor Si Young Song of Yonsei University College of Medicine[15,16]. The EG scan machinery (version I) is composed of an optical probe, a handle for control, and a display monitor. The optical probe is disposable (Figure 1), and the largest diameter is 6 mm, similar to a nasogastric tube with diameter of 16 French (Figure 2). The optical probe can be deflected to 60o upward or 60o downward, but not left or right. The optical probe is inserted though the mouth or nose using display monitor to visualize the process, and the probe can only be used once. The machinery of the full EG scan system is as small as a laptop computer and is portable. It can operate anywhere electric power is supplied. It is easy to use and is accessible for use by a non-GI endoscopist.

The EG scan has the potential to improve the easy and accuracy of diagnosis due to its visual monitoring capabilities for the evaluation of acute GI bleeding in decision making for early conventional upper endoscopy. It is also less painful and has a lower risk of complication than a blindly inserted nasogastric tube. We aimed to test the feasibility of the EG scan to assess GI bleeding for guidance of early conventional endoscopy in patients with acute GI bleeding as an alternative procedure to nasogastric lavage.

Patients who were older than 18 years old and had clinical manifestations suspected of being acute GI bleeding were enrolled in this study. Acute GI bleeding was defined as presentation with hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia within 24 h. Patients who visited the emergency room for acute GI bleeding or in-patients who had been admitted to intensive care unit or general ward and presented with acute GI bleeding in Myongji Hospital were enrolled in this study. Patients with confirmed lower GI bleeding were excluded from this study.

When the patients were hemodynamically stable, an EG scan (version I) was immediately performed at the patients’ bedside by one PGY-4 medical resident. The EG scan’s optical probe was inserted through the mouth using the display monitor to visualize the process. The findings of the EG scan were recorded. Thereafter, conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was instantly performed by one qualified endoscopist, who had not been informed of the findings from the EG scan. The findings from the 2 procedures were compared.

Blood in the stomach was categorized into “active bleeding”, and coffee ground clots and clear fluid were categorized into “inactive bleeding”. In the EGD, high-risk lesions were defined as spurting, oozing of blood, or non-bleeding visible vessels, or by the Forrest classifications Ia, Ib, or IIa[17,18].

To investigate the diagnostic efficacy of the EG scan device, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for active bleeding were calculated, with conventional EGD serving as a reference.

Thirteen patients with acute GI bleeding were enrolled between January and March 2011 (Table 1). Of the 13 patients, 12 patients had symptoms suspicious of upper GI bleeding: 6 patients presented with melena, 3 patients presented with hematemesis, and 3 patients presented with bleeding from a previously located nasogastric tube for feeding or drainage. One patient presented with hematemesis, but the final focus of bleeding was identified as lung cancer.

| No. | Age (yr) | Sex | Reason for endoscopy | Underlying disease/condition | EG scan | EGD | |||

| Performance location | Bleeding status | Bleeding status | Diagnosis | Risk | |||||

| 1 | 52 | M | Hematemesis | Heavy alcoholics | ER | Active | Active | Mallory-Weiss syndrome | High |

| 2 | 47 | F | Hematemesis | Liver cirrhosis | ER | Active | Active | Gastric varix bleeding | High |

| ESRD | |||||||||

| 3 | 87 | M | Hematemesis | Old stroke | ER | Inactive | Active | Gastric ulcer with bleeding | High |

| 4 | 79 | M | Melena | Pneumonia | ICU | Active | Active | Gastric ulcer with bleeding | High |

| Abdominal aorta aneurysm | |||||||||

| 5 | 88 | M | Melena | Cardiac arrest | ICU | Active | Active | Gastric ulcer with bleeding | High |

| Pneumonia | |||||||||

| 6 | 74 | M | Melena | Old stroke | ER | Inactive | Inactive | Duodenal ulcer | Low |

| 7 | 63 | M | Melena | Valvular heart disease | General ward | Inactive | Inactive | Gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcer | Low |

| Coumadin toxicity | |||||||||

| 8 | 85 | F | Melena | Acute myocardial infarction | ICU | Active | Active | Gastric ulcer with bleeding | High |

| 9 | 50 | M | Melena | None | ER | Inactive | Inactive | Duodenal ulcer with visible vessel | High |

| 10 | 72 | F | Blood clots from NG tube for feeding | Stroke | ICU | Inactive | Inactive | Multiple gastric hematin, | Low |

| Parkinson’s disease | |||||||||

| 11 | 89 | F | Fresh blood from NG tube for feeding | Aspiration pneumonia | ICU | Active | Active | Gastric ulcer with bleeding | High |

| 12 | 80 | M | Fresh blood from NG tube for drainage | Postoperative state for gastric cancer | ICU | Active | Active | Anastomosis site bleeding | High |

| 13 | 73 | M | Hematemesis | COPD with acute exacerbation | ER | Active | Active | Hemoptysis (Ingestion of blood from lung cancer) | Not related |

| Lung cancer | |||||||||

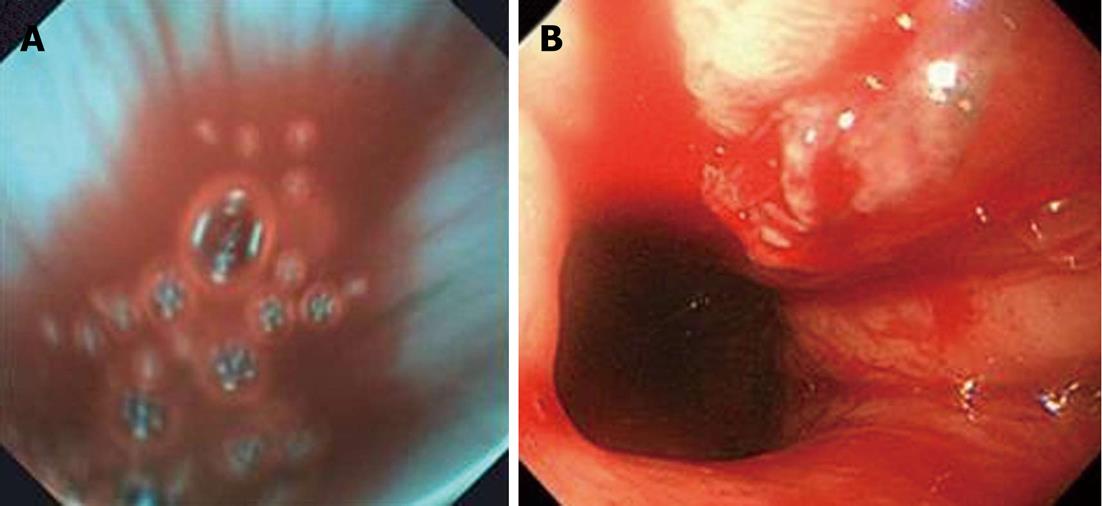

In the 12 patients with upper GI bleeding, 7 patients were diagnosed as having active bleeding by the EG scan, with the same finding by conventional EGD (Figure 3). In 5 patients diagnosed as having inactive bleeding by EG scan, 4 patients were confirmed as having inactive bleeding. The remaining patient was reported as active bleeding by conventional EGD. The sensitivity of the EG scan was 87.5% for active bleeding, and the specificity of the EG scan was 100% for inactive bleeding, with conventional EGD serving as a reference. The positive predictive value for active bleeding was 100%, and the negative predictive value for active bleeding was 80%, with conventional EGD serving as a reference. No complication were reported during the EG scan procedures.

In our small-scale pilot study, the EG scan was shown to evaluate acute upper GI bleeding before conventional EGD in a manner similar to nasogastric lavage. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive values of the EG scan procedure were significant although the results are preliminary. Only one of 12 patients with upper GI bleeding had a discrepancy between the EG scan results and the EGD results. The cause of this discrepancy was possibly a gastric ulcer that had an inactive period of bleeding during the EG scan, whereas blood spurted from the ulcer during the EGD. Therefore, the result was not associated with the accuracy of the EG scan. In a large-scale study using a Canadian retrospective registry, a bloody nasogastric aspirate has a sensitivity of 48.4%, a specificity of 75.8%, and a negative predictive value of 77.9% of for high-risk endoscopic lesions[17]. In a prospective study, 73% of Greek patients with upper GI bleeding and a bloody nasogastric aspirate have active bleeding[19]. In a retrospective cohort study with GI bleeding patients without hematemesis, the sensitivity of a positive nasogastric aspirate is 42%[10]. With respect to these findings, the EG scan is worth consideration of a large-scale controlled study as an alternative procedure to nasogastric lavage.

An EG scan probe can be inserted through a patient’s mouth as it is in conventional EGD. This method can avoid pain during the nasal insertion of a nasogastric tube. The visual monitoring of the EG scan may prevent serious complications related to the blind insertion of a nasogastric tube, such as nasopharynx perforation, esophageal perforation and displacement into the trachea[11,20-22]. In addition, the EG scan’s optical probe can be inserted through a patient’s nose in the same manner in which a nasogastric tube is inserted. In our study, the pain related to the insertion of the EG scan was not investigated and should be part of the evaluation in a further study.

In critically ill patients with other morbidities such as acute myocardial infarction and COPD, conventional EGD has an increased complication rate[23-26]. When these patients are suspected of having acute GI bleeding, it is necessary to exactly assess the acuity, severity, and location of the GI bleeding. In these high-risk patients, the EG scan could play the role of a bridge to conventional EGD by assessing the exact status of GI bleeding. In our study, critically ill patients with acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and pneumonia received an EG scan with high performance and without any complications.

In Korea, the prices of a nasogastric tube and lavage are approximately 10 United States dollars and 20 United States dollars, respectively, whereas the price of a disposable optical probe of EG scan is approximately 100 United States dollars. The cost of performing EG scan is currently more expensive than nasogastric lavage. However, an EG scan may screen active bleeding more precisely than nasogastric lavage and may eventually reduce unnecessary emergency EGDs and costs. The cost and effectiveness of the EG scan must be confirmed through large-scale studies. Additionally, the price of an EG scan could be decreased by advancements in electronics in the future, and this technology could replace nasogastric lavage.

However, the EG scan has several weaknesses. First, EG scan version I does not provide air inflation; therefore, it is difficult to find the focus of the bleeding in the stomach. Recently, an EG scan version II with an air inflation function has been released that could resolve this problem. Second, there is no method to clear the cover glass in front of the camera during the procedure, which means that vision can be impaired when secreted materials become stuck to the cover glass. Additionally, angulation of the head of the optical probe is limited up to 60o upward or 60o downward. Further development of the technique will compensate for these weak points when using the EG scan.

In conclusion, the EG scan was developed for single-use and as a portable device. It is feasible for screening acute upper GI bleeding with high sensitivity and specificity. If larger, controlled trials looking at the predictive value, the cost, patient discomfort, and the relative side effect profile of immediate endoscopy or nasogastric lavage in comparison to the EG scan prove positive, this device has the potential to replace nasogastric lavage or universal urgent EGD in an emergency room, ward or intensive care unit setting.

Nasogastric lavage is an important method to evaluate acute gastrointestinal bleeding. However, the findings of nasogastric lavage sometimes indicate false positive or false negative active bleeding, and nasogastric tube insertion is very painful to patients. A more precise and less painful procedure has been needed.

The EG scanTM (IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) is a novel disposable endoscopy tool using the mechanism of capsule endoscopy, and its machinery is small enough to be portable. It has been developed to be used in outpatient clinics quickly and comfortably.

This is the first study to investigate the diagnostic efficacy of the EG scan for screening active bleeding. The promising results suggest that the EG scan should be a candidate procedure as a substitute to nasogastric lavage, although this is a pilot study with a small sample size.

These preliminary findings suggest that the EG scan may be a substitute for nasogastric lavage. This device can also be used as esophagoscopy in outpatient clinics and as a flexible rectosigmoidoscopy. In the future, the portable nature of this device may enable EG scans to be used for patients in an emergency outside of a hospital.

A single-use endoscopy tool is disposable after use. Early endoscopy is an endoscopic procedure used within 24 h of presentation to diagnose or treat diseases. Active bleeding is defined as the existence of blood in the stomach, and inactive bleeding is defined as the existence of coffee ground clots or clear fluid in the stomach. A high-risk ulcer is one with current bleeding or high risk of bleeding.

This pilot study shows that the EG scan, a novel single-use endoscopy device, can screen active bleeding simply and easily. It is a portable system suitable for fast diagnosis in emergency rooms and intensive care units, although the efficacy should be confirmed in large-scale trials.

P-Reviewers Misra SP, Kozarek RA S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101-113. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Greenspoon J, Barkun A, Bardou M, Chiba N, Leontiadis GI, Marshall JK, Metz DC, Romagnuolo J, Sung J. Management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:234-239. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bardou M, Benhaberou-Brun D, Le Ray I, Barkun AN. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lim LG, Ho KY, Chan YH, Teoh PL, Khor CJ, Lim LL, Rajnakova A, Ong TZ, Yeoh KG. Urgent endoscopy is associated with lower mortality in high-risk but not low-risk nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Stanley AJ. Update on risk scoring systems for patients with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2739-2744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pallin DJ, Saltzman JR. Is nasogastric tube lavage in patients with acute upper GI bleeding indicated or antiquated? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:843-857. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Anderson RS, Witting MD. Nasogastric aspiration: a useful tool in some patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:364-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang ES, Karsan S, Kanwal F, Singh I, Makhani M, Spiegel BM. Impact of nasogastric lavage on outcomes in acute GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:971-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Witting MD, Magder L, Heins AE, Mattu A, Granja CA, Baumgarten M. Usefulness and validity of diagnostic nasogastric aspiration in patients without hematemesis. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pitera A, Sarko J. Just say no: gastric aspiration and lavage rarely provide benefit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:365-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marmo R, Koch M, Cipolletta L, Capurso L, Pera A, Bianco MA, Rocca R, Dezi A, Fasoli R, Brunati S. Predictive factors of mortality from nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1639-1647; quiz 1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singer AJ, Richman PB, Kowalska A, Thode HC. Comparison of patient and practitioner assessments of pain from commonly performed emergency department procedures. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:652-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schlager A, Metzger YC, Adler SN. Use of surface acoustic waves to reduce pain and discomfort related to indwelling nasogastric tube. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1045-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chung JW, Park S, Chung MJ, Park JY, Park SW, Chung JB, Song SY. A novel disposable, transnasal esophagoscope: a pilot trial of feasibility, safety, and tolerance. Endoscopy. 2012;44:206-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bang S, Park JY, Jeong S, Kim YH, Shim HB, Kim TS, Lee DH, Song SY. First clinical trial of the “MiRo” capsule endoscope by using a novel transmission technology: electric-field propagation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Aljebreen AM, Fallone CA, Barkun AN. Nasogastric aspirate predicts high-risk endoscopic lesions in patients with acute upper-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Forrest JA, Finlayson ND, Shearman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet. 1974;2:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 594] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adamopoulos AB, Baibas NM, Efstathiou SP, Tsioulos DI, Mitromaras AG, Tsami AA, Mountokalakis TD. Differentiation between patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding who need early urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and those who do not. A prospective study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:381-387. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tho PC, Mordiffi S, Ang E, Chen H. Implementation of the evidence review on best practice for confirming the correct placement of nasogastric tube in patients in an acute care hospital. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ronen O, Uri N. A case of nasogastric tube perforation of the nasopharynx causing a fatal mediastinal complication. Ear Nose Throat J. 2009;88:E17-E18. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Pillai JB, Vegas A, Brister S. Thoracic complications of nasogastric tube: review of safe practice. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:429-433. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Cappell MS. Gastrointestinal endoscopy in high-risk patients. Dig Dis. 1996;14:228-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yachimski P, Hur C. Upper endoscopy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and upper gastrointestinal bleeding: results of a decision analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:701-711. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cappell MS, Iacovone FM. Safety and efficacy of esophagogastroduodenoscopy after myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 1999;106:29-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lieberman DA, Wuerker CK, Katon RM. Cardiopulmonary risk of esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Role of endoscope diameter and systemic sedation. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:468-472. [PubMed] |