Published online Nov 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i44.6461

Revised: May 16, 2012

Accepted: May 26, 2012

Published online: November 28, 2012

AIM: To examine factors influencing percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) uptake and outcomes in motor neuron disease (MND) in a tertiary care centre.

METHODS: Case notes from all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MND who had attended the clinic at the Repatriation General Hospital between January 2007 and January 2011 and who had since died, were audited. Data were extracted for demographics (age and gender), disease characteristics (date of onset, bulbar or peripheral predominance, complications), date and nature of discussion of gastrostomy insertion, nutritional status [weight measurements, body mass index (BMI)], date of gastrostomy insertion and subsequent progress (duration of survival) and quality of life (QoL) [Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R)]. In addition, the type of clinician initiating the discussion regarding gastrostomy was recorded as Nutritional Support Team (involved in providing nutrition input viz Gastroenterologist, Speech Pathologist, Dietitian) and other (involved in non-nutritional aspects of patient care). Factors affecting placement and outcomes including length of survival, change in weight and QoL were determined.

RESULTS: Case records were available for all 86 patients (49 men, mean age at diagnosis 66.4 years). Thirty-eight patients had bulbar symptoms and 48 had peripheral disease as their presenting feature. Sixty-six patients reported dysphagia. Thirty-one patients had undergone gastrostomy insertion. The major indications for PEG placement were dysphagia and weight loss. Nine patients required immediate full feeding, whereas 17 patients initially used the gastrostomy to supplement oral intake, 4 for medication administration and 1 for hydration. Initially the PEG regime met 73% ± 31% of the estimated total energy requirements, increasing to 87% ± 32% prior to death. There was stabilization of weight in patients undergoing gastrostomy [BMI at 3 mo (22.6 ± 2.2 kg/m2) and 6 mo (22.5 ± 2.0 kg/m2) after PEG placement compared to weight at the time of the procedure (22.5 ± 3.0 kg/m2)]. However, weight loss recurred in the terminal stages of the illness. There was a strong trend for longer survival from diagnosis among MND in PEG recipients with limb onset presentation compared to similar patients who did not undergo the procedure (P = 0.063). Initial discussions regarding PEG insertion occurred earlier after diagnosis when seen by nutrition support team (NST) clinicians compared to other clinicians. (5.4 ± 7.0 mo vs 11.9 ± 13.4 mo, P = 0.028). There was a significant increase in PEG uptake (56% vs 24%, P = 0.011) if PEG discussions were initiated by the NST staff compared to other clinicians. There was no change in the ALSFRS-R score in patients who underwent PEG (pre 34.1 ± 8.6 vs post 34.8 ± 7.4), although in non-PEG recipients there was a non-significant fall in this score (33.7 ± 7.9 vs 31.6 ± 8.8). Four patients died within one month of the procedure, 4 developed bacterial site infection requiring antibiotics and 1 required endoscopic therapy for gastric bleeding. Less serious complications attributed to the procedure included persistent gastrostomy site discomfort, poor appetite, altered bowel function and bloating.

CONCLUSION: Initial discussion with NST clinicians increases PEG uptake in MND. Gastrostomy stabilizes patient weight but weight loss recurs with advancing disease.

- Citation: Zhang L, Sanders L, Fraser RJ. Nutritional support teams increase percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy uptake in motor neuron disease. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(44): 6461-6467

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i44/6461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i44.6461

In patients with motor neuron disease (MND), the management of dysphagia either at diagnosis or developing during disease progression remains a major clinical issue[1-3]. Provision of adequate nutrition is important in these patients as malnutrition and dehydration can increase the rate of disease progression and adversely upset quality of life (QoL)[1]. Although percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) insertion is an important strategy in optimizing nutritional management, the effect of this intervention on survival remains controversial with studies reporting both benefit[2] and lack of effectiveness[3,4]. The reasons for these discrepancies are unclear and may relate, in part, to the timing of PEG insertion in different patient subgroups[4,5]. Weight gain or weight maintenance has been reported as another positive outcome of PEG, but the duration of the effect is also uncertain[2,6]. Although a number of indications, including weight loss and choking have been proposed for PEG insertion in MND[6-8], published data indicate that the procedure is performed in less than 50% of patients, who fulfill these criteria[1]. In part, this may reflect delays in PEG insertion until there is a major clinical deterioration in swallowing[7], although limited data show subclinical abnormalities in pharyngeal function often occur earlier[9]. Thus, it is possible that some patients who might benefit from supplemental nutrition may not receive this at the appropriate time[7].

A number of strategies have been proposed to increase the use of PEG including nutrition education and early discussion of alternative feeding routes[10,11]. It has also been suggested that involvement of multidisciplinary teams may have a role and potentially improve the length of survival [11-13].

The aim of the current study was to examine the factors associated with the uptake and the outcomes of PEG placement in patients with MND being managed in a tertiary referral centre.

A retrospective case note audit was conducted at the Repatriation General Hospital (RGH), a 270-bed university affiliated teaching metropolitan hospital. The study was approved by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee. To preserve patient anonymity, a unique study ID was assigned to each patient, and personal details were kept separate from the research data.

Patients were included in this study if they had attended RGH for management of MND, and had died between January 2007 and January 2011. All diagnoses of MND were confirmed by one or two neurologists based on El Escorial criteria after appropriate clinical examinations and investigations. Patient characteristics including gender, age, dates of MND onset and diagnosis, presentation features of MND, and complications (the presence of respiratory insufficiency, dysphagia and dementia) were recorded.

The type of MND was classified as either bulbar or limb disease according to symptoms at presentation. Patients with both bulbar and limb symptoms were classified as having bulbar disease.

To assess nutrition status, weights at four times were determined: usual (prior to diagnosis of MND), at diagnosis, at assessment (when the dietetic service was involved), and at death. In patients undergoing gastrostomy, the weight at PEG insertion, and 3 and 6 mo post-procedure were also recorded. Body mass index (BMI) and percentage weight loss (PWL) were also calculated over time.

To assess the role of different clinical groups in PEG management in MND, the type of clinician initiating the discussion of PEG, dates of initial PEG discussion and PEG insertion, and reasons for accepting or declining the procedure, together with the rationale for PEG were recorded. Clinicians with expertise in PEG insertion and management (dietitian, gastroenterologist or speech pathologist) were considered as a nutritional support team (NST). Other clinicians involved in MND management were recorded individually (e.g., palliative care physicians, neurologists, specialist nurses, sleep registered nurses, rheumatologists and general physicians) and grouped as other.

To evaluate the effect of PEG placement on QoL, the results from the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R)[14] were obtained from the Palliative Care MND clinic at the RGH. Scores were extracted from the records at the closest time prior to (≤ 1 to 5 mo) (Q1) and after (≤ 1 to 5 mo) (Q2) PEG insertion in these patients. For non-PEG patients, ALSFRS-R assessments at “correlated” time points Q1’ and Q2’, corresponding to the mean interval before and after PEG insertion were used for comparison.

The outcomes in terms of formula delivery and level of nutrition support as well as any complications of PEG placement were also recorded.

Extracted data were entered into a spreadsheet and analysed using Predictive Analytics Software Statistics Version 18.0.3 for Windows (PASW, formerly SPSS, SPSS Inc., 2010, Chicago, IL, United States). Patient characteristics were recorded as mean ± SD and counts (percentages). Categorical data were compared by χ2 tests. Continuous data between groups and within groups were compared by independent-sample T tests and paired-samples T tests, respectively. P≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

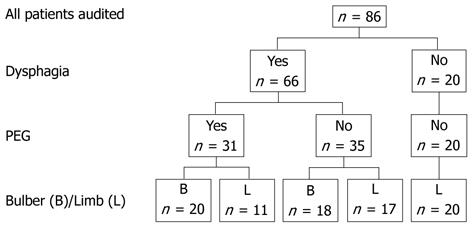

Case records were available for all 86 patients with MND who attended the hospital and met the selection criteria. Demographic and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. The breakdown of the number of patients according to the type of MND, presence of dysphagia and PEG insertion are shown in Figure 1.

| Males | 49 (57) |

| Type of MND | |

| Bulbar as predominant symptom | 38 (44) |

| Limb as predominant symptom | 48 (56) |

| Age at symptom onset (yr) | 65.0 ± 13.7 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 66.4 ± 13.0 |

| Survival after PEG placement (mo) | 11.3 ± 10.1 |

| Living arrangements | |

| Alone | 13 (15) |

| With spouse | 50 (58) |

| With other family member | 10 (12) |

| Care facility | 7 (8) |

| Not recorded | 6 (7) |

| Complications during illness | |

| Dysphagia | 66 (77) |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 47 (55) |

| Dementia | 5 (6) |

| Symptom onset to PEG placement (mo) | 20.3 ± 8.0 |

| Diagnosis to PEG placement (mo) | 10.8 ± 8.3 |

In total, 31 subjects underwent PEG placement using a pull technique with either a 20 Fr (n = 28) or an 18 Fr device. All of these patients had dysphagia. Patients with bulbar presentation (20/38, 53%), were more likely to have PEG inserted than those presenting with limb symptoms (11/48, 23%, P = 0.004).

PEG placement was discussed with 75.6% (65/86) patients, 92.1%, with bulbar (35/38) and 62.5% with limb onset (30/48). The NST initiated these discussions in 36 patients and other clinicians in 29 patients. There was a significant increase in the percentage of patients undergoing PEG when the initial discussions were held with the NST (56% vs 24%, P < 0.02, Table 2). In addition, these patients had longer time from symptom onset to diagnosis, and a shorter time from diagnosis to PEG. There was no difference in the time from the initial discussion to the procedure between the groups.

| Nutritional support team | Other clinicians | P value | |

| Initial PEG discussions, n | 36 | 29 | |

| Patients undergoing PEG insertion after initial discussion, n | 20 (56%, 20/36) | 7 (24%, 7/29) | 0.011 |

| MND symptom onset to MND diagnosis, mo | 12.8 (± 7.5), n = 26 | 8.4 (± 3.9), n = 17 | 0.017 |

| MND diagnosis to initial PEG discussion, mo | 5.4 (± 7.0), n = 20 | 11.9 (± 13.4), n = 6 | 0.028 |

| Initial PEG discussion to placement, mo | 3.5 (± 3.3), n = 20 | 4.4 (± 3.2), n = 6 | 0.572 |

| PEG placement to death, mo | 12.9 (± 11.1), n = 20 | 8.8 (± 10.1), n = 6 | 0.422 |

| MND symptom onset to death, mo | 30.0 (± 13.2), n = 26 | 31.2 (± 13.2), n = 17 | 0.740 |

| MND diagnosis to death, mo | 18.0 (± 15.6), n = 36 | 21.6 (± 15.6), n = 27 | 0.393 |

The major reason for having a PEG inserted was dysphagia (n = 26), with severe weight loss (n = 4) and prophylaxis (n = 1) also recorded. The reasons for PEG insertion not proceeding after discussion (n = 38) were patient preference (n = 17), death before PEG placement [n = 9, (4 discussed with NST, 5 with other)] and lack of medical fitness for procedure (n = 1). In 11 patients no reason for refusal was recorded. In patients who died before the PEG could be undertaken, 4 instances were due to advanced disease and respiratory failure preventing the safe performance of the procedure. Two of these were initially discussed with NST and 2 with other clinicians. Of the other 5 patients (2 NST, 3 other) the patients initially agreed to the gastrostomy but then failed to proceed with the procedure.

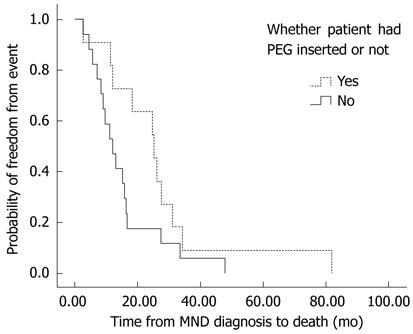

Regardless of the presentation (i.e., bulbar or limb), there was a trend towards longer survival in MND patients with dysphagia after PEG insertion (21.6 ± 15.6 mo), compared to patients who had dysphagia, but did not undergo the procedure (16.8 ± 11.0 mo, P = 0.089). This increased length of survival reflected the effect in patients with limb onset MND who developed dysphagia (PEG: 26.4 ± 20.4 mo vs non-PEG: 14.4 ± 10.8 mo, P = 0.063) (Figure 2) as in bulbar MND patients there was no difference in survival with or without PEG (19.2 ± 12.0 mo vs 18.0 ± 10.8 mo, P = 0.656).

PEG insertion was accompanied by stabilization of patient weight 3 and 6 mo after placement. In contrast, patients who did not undergo PEG placement had ongoing weight loss. However, further weight loss occurred in all patients as MND progressed (Table 3). Thus, the mean BMI for PEG patients decreased significantly from usual weight to diagnosis (P = 0.003), diagnosis to assessment for PEG (P = 0.001) and from this assessment to death (P = 0.023). There was a trend for PEG to be offered to patients who had greater weight loss from diagnosis to assessment (PWL of PEG patients: 5.9% ± 7.0% vs PWL of non-PEG patients with dysphagia: 2.3% ± 6.5%, P = 0.076).

| Time points | n1 | Body mass index (mean ± SD) kg/m2 |

| Usual | 20 | 26.6 ± 4.3 |

| Diagnosis | 23 | 25.3 ± 4.0 |

| Assessment | 25 | 23.8 ± 3.6 |

| PEG insertion | 25 | 22.5 ± 3.0 |

| 3 mo post-PEG | 16 | 22.6 ± 2.2 |

| 6 mo post-PEG | 13 | 22.5 ± 2.0 |

| Death | 16 | 21.2 ± 2.2 |

| Percentage of weight loss (mean ± SD) | ||

| Usual to diagnosis | 22 | 5.8 ± 7.5 |

| Diagnosis to assessment | 26 | 5.9 ± 7.0 |

| Assessment to PEG insertion | 28 | 5.9 ± 5.9 |

| PEG insertion to 3 mo after | 18 | -0.1 ± 6.02 |

| 3 to 6 mo post-PEG | 13 | 1.4 ± 5.1 |

| 6 mo post-PEG to death | 12 | 2.4 ± 4.9 |

Initially, 17 patients used PEG to supplement oral intake; nine required immediate full feeding; four used PEG for medication administration and one for hydration. Eight patients were nil by mouth. Initially the feeding regime met 73% ± 31% of the estimated total energy requirements and this increased to 87% ± 32% prior to death.

Fifty-nine patients (68.6%) had at least one assessment with the ALSFRS-R performed during their illness. There was no change in the ALSFRS-R score in patients who underwent PEG (34.1 ± 8.6, n = 19 at Q1 and 34.8 ± 7.4, n = 17 at Q2). Interestingly, in patients who did not undergo PEG placement, there was a non-significant fall in the ALSFRS-R score from 33.7 ± 7.9 (n = 31) at Q1’ to 31.6 ± 8.8 (n = 18) at Q2’. There was no significant difference between Q1 and Q1’ (P = 0.886), or Q2 and Q2’ (P = 0.252).

Possible adverse effects related to the procedure were recorded in 19 patients after PEG insertion. These included pain at the site of the gastrostomy at follow up (n = 9), poor appetite (n = 4), bacterial site infection requiring antibiotics (n = 4), death within 30 d (n = 4, respiratory failure), nausea (n = 3), constipation (n = 2), diarrhea (n = 2), vomiting (n = 2), bloating (n = 1) and gastric hemorrhage (n = 1).

The new findings from this study are that initial discussions of PEG insertion by a NST significantly increases the uptake of PEG by patients with MND, compared to when discussions were initiated by other clinicians. There was also a trend for increased survival for patients with limb onset disease who had a PEG, but not for patients with bulbar onset disease. Consistent with previous studies, PEG placement initially arrested weight loss, although with disease progression patients again lost weight prior to death. Data on the QoL were incomplete but no decrease was seen in the ratings in patients undergoing PEG placement.

Previous reports suggest that the uptake of PEG is approximately 20%[1], although up to 80% of MND patients developed dysphagia at some point in their illness. The reasons for this are unclear, but may reflect lack of enthusiasm by both patient and clinicians about a procedure whose value remains uncertain. Also, patients may lack sufficient information about the procedure and its implications. Additionally in some patients, respiratory dysfunction may present a contraindication to gastrostomy by preventing safe performance of the procedure[9].

The current report extends previous data showing that involvement of multidisciplinary teams in the care of patients with MND enhances the uptake of interventions, including gastrostomy[10,12,15,16]. In this study, possible PEG placement was discussed with the majority of patients regardless of the presence of dysphagia or the type of presentation of MND. However, the initiation of discussion by clinicians with a background in nutrition significantly increased the patients’ uptake of PEG insertion. It is possible that clinicians familiar with MND are more aware of the importance of nutrition adequacy in MND management and clinicians who are closely involved in management of PEG insertions are able to better allay patients’ concerns. Furthermore, the NST raised the topic significantly earlier than other clinicians after diagnosis, which potentially allowed more time for the patients to adjust to the concept and undergo PEG insertion before their overall condition deteriorated. The time from PEG discussion to PEG insertion was similar between these two clinician groups suggesting that patients were not simply referred to the NST when nutrition was inadequate. Overall survival of patients undergoing PEG placement was similar irrespective of their referring clinician, suggesting that there was no difference in the patients with whom the procedure was discussed to explain the difference in uptake.

The effect of PEG feeding on survival in patients with MND has been controversial. It is possible that differences in reported outcomes may reflect the different subtypes of MND undergoing the procedure as well as the timing of the procedure[2-6,9]. In the current study, there was a strong trend for prolonged survival after PEG, but only in those patients with limb onset disease. The reasons for this are unclear. An early study[2] suggested that PEG prolonged survival significantly in MND patients with bulbar symptoms, including those in whom dysphagia developed at any stage. However, in this study the symptoms at presentation (i.e., bulbar or limb) were not defined[2]. Another case control study[5] found no significant survival benefit of the use of PEG, but PEG was associated with prolonged survival in their whole study cohort and among those with bulbar onset; the reasons for this discrepancy are unclear but may reflect an older patient profile in the current study. Forbes et al[3] found no survival difference, and in their study limb onset patients fared worse than bulbar onset patients, although the survival in this study was shorter than in the present study. Strong et al[4] found that gastrojejunostomy was associated with shorter survival in either bulbar onset or limb onset patients; however, the control group in this study contained patients who did not require PEG placement and therefore might have had better nutrition status initially.

Maintaining a patient’s weight is a possible advantage of PEG in nutrition management in MND, but the duration of this effect is unclear. In the present study, the patients’ weight stabilized for six months after PEG placement, but with disease progression, patients again lost weight. Weight gain at three months post-PEG has been previously described[5,6], but only one report[2] has described ongoing weight gain over 12 mo post-gastrostomy. In that study, the patients’ baseline BMI prior to PEG insertion was lower (19.7 kg/m2) than in the present study (22.5 kg/m2) and this may explain the discrepancy.

The benefits of PEG in prolonging survival and maintaining weight did not reach statistical significance in this study, and may have reflected a bias in patient selection, since patients who underwent PEG placement had more severe weight loss. Several studies have concluded that lower PWL prior to PEG placement is associated with longer survival[5]. This suggests that early recognition of weight loss may be important to optimize timing of the procedure[7]. Consequently PWL has been recommended as the best indicator of malnutrition and for the referral for PEG, rather than BMI[5,12,16]. In the United Kingdom, using ≥ 10% PWL from baseline has been preferred as an indicator for PEG insertion instead of BMI in MND patients[17]. An Irish review suggested that PEG was warranted when 5%-10% of weight loss was observed in MND patients[18], and Chiò et al[5] found that patients with PWL ≥ 10% fared worse after PEG placement. Thus, the optimal timing remains uncertain[1,9]. In the current study, an additional interesting finding was that, consistent with other reports[18], patients experienced rapid weight loss prior to death even with PEG nutrition. The reasons for this are unclear. Although overall PEG feeding did not achieve 100% of the feeding goals (reflecting the desire to provide supplemental feeding/hydration in some patients, and voluntary restriction in others in the terminal phase of their illness) overall nutrition intake appeared adequate. It is possible that loss of muscle mass with disease progression[19] and increased energy requirement due to respiratory insufficiency[18] may be important contributory factors.

A further potential benefit from PEG insertion in MND patients has been the potential to improve QoL[6], but this has not been systematically assessed[1,2,3,17]. In the current study, ALSFRS-R scores were maintained after the gastrostomy PEG. However, interpretation of the data is limited, in part because of difficulties in obtaining comparable data between PEG and non-PEG patients. In addition, the comparison of QoL is likely to be affected by the severity of dysphagia before PEG placement which in itself contributes to the probability of the procedure[8]. Also, adverse effects associated with gastrostomy placement are likely to reduce any positive effects[1]. Although weight loss, pain and poor appetite have been identified as indicators of decreased QoL[1,6], their relationship to PEG placement is difficult to assess.

The retrospective nature of the current study means that some caution is required in the interpretation of the data. Thus, although data from all patients with MND seen at the hospital were included in the study, it is impossible to exclude biases due to patient referral. However, the demographics of the patient group are similar to those reported previously. Moreover, as the hospital provides state-wide palliative care for the majority of patients with MND, data are likely to be representative of Australian patients with the condition. Although nutritional advice provided by services external to the hospital was not obtained, it seems unlikely that this impacted significantly on patient care.

In conclusion, initial discussion about PEG placement with a nutrition support team increased the uptake of PEG in patients with MND. Gastrostomy insertion was associated with a strong trend towards longer survival of patients with dysphagia who had limb onset but not bulbar disease. In patients undergoing PEG placement there was initial stabilization of weight, but with disease progression patient weight again decreased.

Although the importance of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding to facilitate nutrition support and reduce sarcopenia (potentially decreasing the rate of disease progression) is well recognised in patients with motor neuron disease (MND), only a minority of suitable patients undergo the procedure. The reasons for this are likely to be multifactorial, but may include the availability of information about the intervention. Multidisciplinary management of MND is associated with better uptake, but the reasons for this are uncertain.

Currently only supportive therapy such as enteral nutrition is available for MND, but who should receive this and when is unclear. Increased knowledge on which sub-groups of patients are assisted by PEG feeding and the timing of the gastrostomy insertion allows patients and clinicians to make more informed decisions to optimize the benefits.

Patients who received counseling from a Nutrition Support Professional were more likely to undergo the procedure. Interestingly the patients with peripheral onset of disease had a trend to longer survival consistent with the concept that muscle mass is preserved by adequate nutrition.

The findings support the use of multidisciplinary teams in this disease and also provide a possible rationale for the findings of better survival in units where this is undertaken.

MND is a progressive neurological condition of unknown aetiology characterized by relentless progression to respiratory failure.

Well written manuscript (retrospective study) regarding PEG tube utilization in patients with MND. It provides some new inside to early PEG placement in patients with malnutrition and MND.

Peer reviewer: Andrew Ukleja, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Cleveland Clinic Florida, 2950 Cleveland Clinic Blvd., Weston, FL 33331, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Katzberg HD, Benatar M. Enteral tube feeding for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD004030. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mazzini L, Corrà T, Zaccala M, Mora G, Del Piano M, Galante M. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and enteral nutrition in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 1995;242:695-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Forbes RB, Colville S, Swingler RJ. Frequency, timing and outcome of gastrostomy tubes for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease--a record linkage study from the Scottish Motor Neurone Disease Register. J Neurol. 2004;251:813-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Strong MJ, Rowe A, Rankin RN. Percutaneous gastrojejunostomy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chiò A, Finocchiaro E, Meineri P, Bottacchi E, Schiffer D. Safety and factors related to survival after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in ALS. ALS Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Study Group. Neurology. 1999;53:1123-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vuolo G, Tirone A, Cesaretti M, Chieca R, Guarnieri A, Verre L, Greco G, Malentacchp M, Gianninp F, Pirrelli M. Evaluation of nutritional status before and after PEG placement in patients with motor neuron disease. Nutr Ther Metabol. 2008;26:137-140. |

| 7. | Mitsumoto H, Davidson M, Moore D, Gad N, Brandis M, Ringel S, Rosenfeld J, Shefner JM, Strong MJ, Sufit R. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in patients with ALS and bulbar dysfunction. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2003;4:177-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, England JD, Forshew D, Johnston W, Kalra S, Katz JS, Mitsumoto H, Rosenfeld J. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1218-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 532] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Higo R, Tayama N, Nito T. Longitudinal analysis of progression of dysphagia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Neurosciences and the Senses Health Network, Motor Neurone Disease Project Group, Western Australia, Department of Health, Health Networks Branch. Motor neurone disease services for Western Australia. Subiaco, Western Australia: Health Networks Branch 2008; . |

| 11. | Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, England JD, Forshew D, Johnston W, Kalra S, Katz JS, Mitsumoto H, Rosenfeld J. Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2009;73:1227-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 437] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rio A, Cawadias E. Nutritional advice and treatment by dietitians to patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease: a survey of current practice in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Canada. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2007;20:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chiò A, Bottacchi E, Buffa C, Mutani R, Mora G. Positive effects of tertiary centres for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on outcome and use of hospital facilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:948-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, Fuller C, Hilt D, Thurmond B, Nakanishi A. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. BDNF ALS Study Group (Phase III). J Neurol Sci. 1999;169:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2047] [Cited by in RCA: 2489] [Article Influence: 95.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, Frost E, Hardiman O. Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996-2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1258-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rio A, Ellis C, Shaw C, Willey E, Ampong MA, Wijesekera L, Rittman T, Nigel Leigh P, Sidhu PS, Al-Chalabi A. Nutritional factors associated with survival following enteral tube feeding in patients with motor neurone disease. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Leigh PN, Abrahams S, Al-Chalabi A, Ampong MA, Goldstein LH, Johnson J, Lyall R, Moxham J, Mustfa N, Rio A. The management of motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74 Suppl 4:iv32-iv47. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hardiman O. Symptomatic treatment of respiratory and nutritional failure in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 2000;247:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | The Motor Neurone Disease Australia Publication Review Committee. Motor neurone disease aspects of care: for the primary health care team. 3rd ed. Gladesville NSW: MND Australia 2011; . |