CASE REPORT

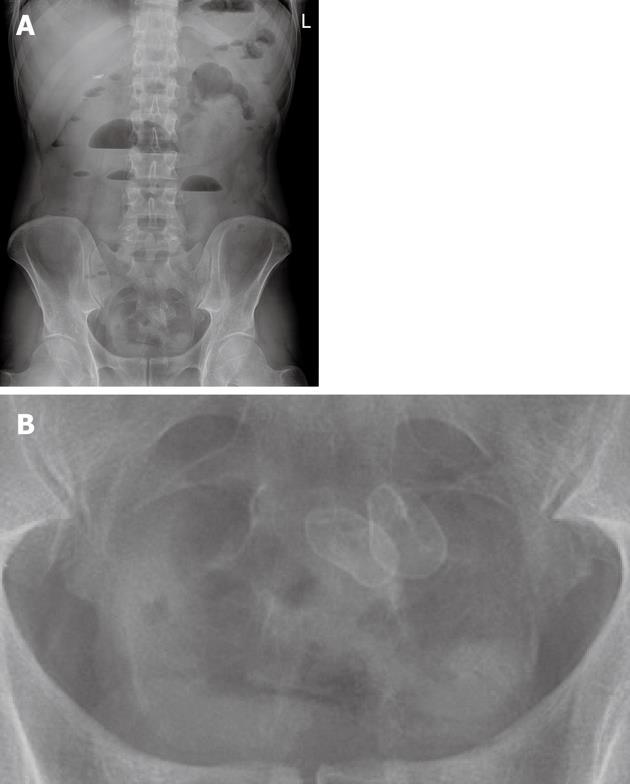

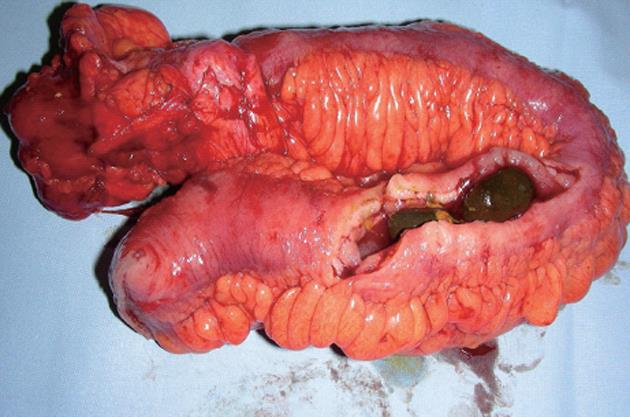

A 46-year-old male patient (nonsmoker) presented with acute diffuse abdominal pain, constipation and vomiting at the emergency unit of the department of surgery. His past medical history included laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis several years ago and a 12-year history of Crohn’s disease. At the time of admission the patient was treated with budesonide, enteroclysma and 5-aminosalicylic acid (A2L3B1 Montreal Classification for Crohn’s disease 2005). The clinical examination showed no fever, a soft, but distended abdomen without abdominal guarding. Blood investigation revealed a normal leucocyte count and a marginally increased level of C-reactive protein. On the abdominal X-ray, the typical imaging of an incipient small bowel ileus with dilated small bowel loops was apparent (Figure 1A), however, two conspicuous small shadows in the pelvis were also observed (Figure 1B). Consequently, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen was performed to confirm or exclude a mechanical obstruction. The CT scan showed a significant small bowel stricture and two adjacent intraluminal radiopaque, dense calcified enteroliths with a maximal diameter of 20 mm in the terminal ileum with significant wall thickening, acute inflammatory signs and prestenotic dilatation of the small bowel indicating a mechanical ileus (Figure 2). The patient underwent immediate emergency laparotomy: the intraoperative findings revealed a long (30 cm), dense narrowing of the terminal ileum with irremovable stony palpable masses, poststenotic emptiness and prestenotic dilatation of the bowel (Figure 3). An ileocoecal resection of about 40 cm of the terminal ileum with a side to side ileoascendostomy reconstruction was conducted (Figure 4). Histopathological examination of the resected specimen confirmed the diagnosis of an acute inflammatory episode of Crohn’s disease without any sign of malignant transformation or perforation. After an uneventful postoperative stay of 11 d, the patient was discharged home with Crohn’s disease specific medication (metronidazole, azathioprine) recommended by the gastroenterologists to prevent postoperative bacterial infection and to control inflammatory activity.

Figure 1 X-ray of the abdomen with two small radiopaque enteroliths in the lower abdomen.

A: Overall picture; B: Enlarged detail. L: Left.

Figure 2 Computed tomography images with two radiopaque enteroliths.

Figure 3 Intraoperative illustration of the small bowel ileus with evident stenosis and prestenotic dilation.

Figure 4 Resected specimen of the cecum and small bowel with two fixed enteroliths causing small bowel obstruction.

DISCUSSION

The first description of enterolithiasis in the scientific literature can be traced back to 1917, when Pfahler et al[3] published a report on the radiological features of enterolithiasis. It was not until 1959 that Atwell et al[4] introduced the definition of enteroliths as “endogenous foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract”. According to a classification by Grettve et al[5], enteroliths can be divided into primary and secondary enteroliths. Primary enteroliths always develop inside the bowel, and can be caused by concretions of normal chylus components such as choleic acid, calcium phosphate and calcium carbonate (so called “true” primary enteroliths) or by ingested indigestible material such as hair (trichobezoar), vegetables (phytobezoar) or other exogenous substances such as barium sulfate (so called “false” primary enteroliths). In contrast, secondary enteroliths typically form outside the bowel and then pass into the bowel like gallstones which fistulate into the bowel causing peritonitis and/or mechanical obstruction. The most common localization of enteroliths is the colon including the appendix vermiformis (appendicoliths), however, enteroliths can occur throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract from the stomach to the rectum.

Stasis or decelerated motility of the gastrointestinal tract seems to be the crucial pathogenetic factor in the development of enteroliths, since an unimpaired continuous flow of the gastrointestinal content usually does not allow the formation of enteroliths[5]. However, when stasis occurs, small particles have enough time to crystallize and form accumulating stones. Stasis is always associated with anatomic alterations of the gastrointestinal tract such as harmless anatomic variations (diverticula, duplication cysts)[6,7] or pathologic conditions (strictures) due to bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease or tuberculosis[8-10]. In addition, stasis may also develop after bowel resection with a broad side to side enteroanastomosis with a big blind pouch allowing for continuous deposition of intestinal contents[11]. Enteroliths can be asymptomatic and dissolve spontaneously passing slowly through the gastrointestinal tract until excretion. However, in most cases enterolithiasis is associated with recurrent signs of intestinal obstruction and intermittent abdominal pain. In addition, refractory chronic anemia and perforation have also been reported[4,12]. Interestingly, the patient in our case report did not really suffer from any of these symptoms, although both enterolithiasis and Crohn’s disease represent chronic disorders. Obviously, there was a moderate postinflammatory, quite asymptomatic stricture of the terminal ileum which permitted very slow but continuous development of enteroliths without significant alteration of intestinal passage. The actual inflammatory episode then led to complete intestinal obstruction due to thickening of the bowel wall. We suggest that the enteroliths developed primarily on site, since they were almost completely fixed in the diseased bowel segment. Additionally, the enteroliths stood out with a very hard consistency and blank-looking, polished surface (Figure 5A). About 20 cm proximal of the stricture another enterolith was detected in the resected specimen with completely different characteristics: this enterolith was morbid, fragile, rough and easily movable, potentially because there was no stricture (Figure 5B). We hypothesize that this additional enterolith represents the typical status nascendi of an enterolith which is usually not observable, since it is asymptomatic and potentially excreted.

Figure 5 Typical images of enteroliths.

A: Long-standing enterolith with blank-looking polished surface; B: Emerging enterolith with a rough and fragile surface.

The radiological diagnosis of enteroliths depends on their calcium content[13,14]. In our case, two radiopaque enteroliths were clearly visible on abdominal X-ray, whereas the third mobile enterolith was not detectable. The differential diagnosis of radiopaque enterolith-like alterations includes gallstones, urolithiasis-calcified lymph nodes or pancreatic calcifications. Of note, enteroliths may change their localization on radiographs due to the mobility of the small bowel[9].

Due to its typical strictures impairing the intestinal flow, Crohn’s disease offers favorable conditions for the development of enteroliths. Nevertheless, enteroliths are a very rare condition in Crohn’s disease, since most patients never become symptomatic or because symptoms are not attributable to enteroliths. Studies have proven that enterolithiasis in Crohn’s disease occurs only in patients with a long history of the disorder and long duration of symptoms of between 7 and 40 years (median 15.7 years)[9]. Additionally, a few cases of enterolithiasis-associated adenocarcinomata have been reported in the literature[15]. In summary, there is no evidence for prophylactic treatment of asymptomatic enterolithiasis in Crohn’s disease, although enteroliths represent clear indicators of a stenotic condition. Patients with intestinal obstruction require laparotomy with stricturoplasty or segmental bowel resection.