CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old man with abdominal pain came to emergency room (ER) at 8 PM. He started to feel abdominal discomfort 6 h before. He began experiencing severe sharp abdominal pain with a sudden onset 3 h before. The pain persisted even after the patient took some antacid drug at home. He recalled that he had dinner with fish the previous night. He appeared acutely ill without any vomiting, shortness of breath, diarrhea or fever. At the time of his arrival in the ER, he was alert and oriented. His blood pressure was 144/86 mmHg, heart rate 72 beats/min, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, and body temperature 37.1 °C. He reported no past history of hypertension, diabetes or abdominal surgery. The initial physical examination revealed normal breathing sounds and regular heart beat without murmur. He had normal active bowel sounds and diffuse abdominal tenderness particularly over the right lower quadrant abdomen, coupled with muscle guarding and rebounding pain. Focus echogram showed no ascites, distended gall bladder with murphy’s sign on sonography, or hydronephrosis. Radiography of the kidney-ureter-bladder revealed normal bowel gas without signs of intestinal obstruction or free air. Serum laboratory examinations showed white blood cell count of 10 100/μL, neutrophils of 82.2%, lymphocytes of 12.1%, hemoglobin of 14.8 g/dL, and platelet count of 210 000/μL. Serum biochemistry tests revealed a glucose level of 121 mg/dL, and aspartate aminotransferase of 27 U/L, cereal third transaminase of 43 U/L, total bilirubin of 0.5 mg/dL, direct bilirubin of 0.2 mg/dL, creatinine of 1.3 mg/dL, and Na+/K+ of 145/3.8 mEq/L. After primary ER medical treatment with intravenous tenoxicam 20 mg and buscopan 20 mg, his pain was localized to the right lower quadrant abdomen, but rebounding pain was still noted. Abdominal CT revealed a 26 mm radiopaque linear shadow transversely lodged in the distal ileum with thickened wall, which is consistent with signs of fish bone retention. Minimal peritoneal contamination without pneumoperitoneum or abscess formation was noted. A normal appendix was identified. A fish bone-induced micro-perforation in the distal ileum was highly suspected (Figure 1).

Figure 1 An unenhanced abdominal computerized tomography image reveals a 26 mm in length radiopaque linear shadow in the distal ileum lodged into the thickened intestinal wall at both ends (black arrow).

Minimal peritoneal contamination without pneumoperitoneum, or abscess formation is noted, which is consistent with signs of fish bone induced micro-perforation.

A general surgeon was consulted. The patient and his families were informed of the indication for surgical intervention and the option of a more conservative medical treatment. Given the nature of micro-perforation, the patient’s good overall health condition, and the early diagnosis (6 h after symptom onset) before sepsis signs developed, initial medical treatment was elected to manage the patient’s condition, instead of surgical intervention with the consent of the patient and his families.

Intravenous saline hydration without oral intake, subacillin (ampicillin 2 g + sulbactam 1 g) and SABS (metronidazole) 500 mg were provided at ER. After admission to the ward, fever was noted up to 38 °C in the first 2 d. Subacillin 1.5 g iv every 8 h was prescribed for 5 d, followed by Soonmelt (amoxicillin 250 mg/clavulanic acid 125 mg) one tablet orally every 8 h for 7 d. During the first day of admission, the pain score went down from 10 to 3. Rebounding pain and muscle guarding also subsided. However, tenderness over the right lower quadrant abdomen and the periumbilical area was still noted.

On the fourth day, the patient felt hungry and experienced no more abdominal pain or tenderness. Laboratory examinations revealed white blood cell (WBC) count of 3700/μL, neutrophils of 49.7%, lymphocytes of 37.3%, hemoglobin of 14.1 g/dL, platelet count of 227 000/μL and a C-reactive protein level of 2.97 mg/dL (normal < 0.5 mg/dL). As a result of the improved clinical condition, an oral soft diet was initiated. The patient was tolerant of the soft diet without any deterioration of symptoms. A follow up abdominal CT without contrast, which revealed the radiopaque linear shadow still lodged in the same intestinal segment, was performed on the fourth day. The fish bone rotated and became parallel to the distal ileum lumen with one end penetrating out the intestinal wall into the mesenteric fat. Minimal local inflammatory infiltration was seen around the protruding part. No free air or abscess was noted (Figure 2). There was no surgical intervention because clinical symptoms had been completely resolved. The patient was discharged on the sixth day with normal oral intake and stool passage. At 3- and 6-mo follow-ups with the patient, no recurrent abdominal pain or complication was noted.

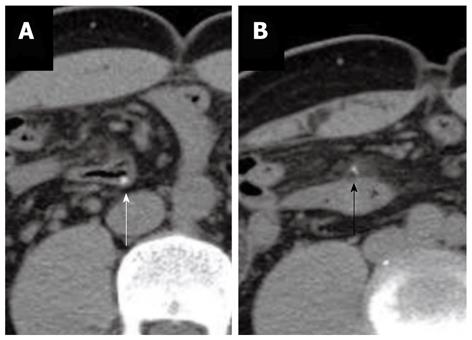

Figure 2 Two follow-up unenhanced abdominal computer tomography images, which reveal the radiopaque shadow still lodged in the intestinal segment.

The fish bone rotates and becomes parallel to the distal ileum lumen. A: Most of the fish bone is still inside the intestinal lumen (white arrow). One end of the fish bone penetrates out the intestinal wall into the mesenteric fat; B: Minimal local inflammatory infiltration contains the protruding part. No free air or abscess is noted (black arrow). The distance between these two images is 18 mm.

DISCUSSION

Unintentional, unconscious foreign body ingestions in adults are usually dietary. Nearly two-thirds of foreign bodies are fish bones[2]. However, most digested foreign bodies pass through the GI tract within a week, and seldom cause major complications[1,9-12]. The ingestion of foreign bodies results in gastrointestinal perforations in less than 1% of patients. Fish bones are the most common objects leading to gastrointestinal perforation[1]. The most common perforation site is the distal ileum[2]. Clinical presentations of GI tract perforation caused by digested foreign bodies vary from case to case, and can be acute, subtle, chronic or even asymptomatic[2,13,14]. The clinical presentations include acute peritonitis, abdominal wall tumor or abscess[2,15], intra-abdominal mass and abscess formation[2,16]. Patients who experience gastric and duodenal perforation tend to present with highly acute pain due to a rapid chemical peritonitis, often followed by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which can lead to rapid clinical deterioration[8,17,18]. Patients often recall the exact time of symptom onset. The perforation may progress to an infected peritonitis and sepsis in untreated patients or in patients who have late-stage presentations[8]. Colon perforations may present without immediate perforation-associated pain and tend to have a slower clinical progression, with the development of a secondary bacterial peritonitis or localized abscess formation partly due to the relatively neutral and non-erosive nature of the chemical environment within the colon[19-21]. Because of the variety of clinical manifestations, the correct preoperative diagnosis is seldom made. Goh et al[2] reported that a correct preoperative diagnosis was made in only 10 (23%) of 44 patients. Furthermore, only a few patients can recall foreign body ingestion. In the report of Goh et al[2], only one (2%) patient provided a definitive history of foreign body ingestion.

Plain radiographs are usually unhelpful with a sensitivity of 32% for fish bones, which varies according to species[22,23]. CT scan is preferred and will usually demonstrate a linear calcified lesion, which if initially missed, can be seen in retrospect. Goh et al[1] reported that the sensitivity of a CT scan in the detection of intra-abdominal fish bones was 71.4% (5/7) in initial reports. Gastrointestinal perforation causes considerable mortality and usually requires emergency surgery. Mortality of secondary peritonitis is still 30% to 50% despite advances in antibiotics, surgical technique, radiographic imaging, and resuscitation therapy[7,8]. The reported indications for surgical intervention are as follows: (1) bowel perforation; (2) peritonitis due to bowel perforation; (3) migration to other organs adjacent to the perforation site; (4) bleeding or severe inflammation in the abdominal cavity; (5) penetration of vessels; and (6) abscess formation[24]. Nonsurgical management highly depends on the time of diagnosis, location and size of the perforation, degree of contamination, and condition of the patient. Nonsurgical management can be successful in stable patients who have minimal signs and symptoms of peritonitis and who have small injuries to the stomach, duodenum, and retroperitoneal portions of the colon[25]. These locations offer possible anatomic containment of the perforation by the retroperitoneal space or omentum. Perforations of the intra-peritoneal small bowel and colon usually require surgery, except for micro-perforations. Micro-perforations often cause minimal peritoneal contamination and can seal spontaneously[25,26]. Micro-perforation means puncture of intestine wall but no CT evidence of free air, purulent peritoneum or abscess. Selected colon perforations, such as certain iatrogenic injuries or perforation secondary to diverticulitis may also be managed non-operatively. Spontaneously sealed perforations and perforations that are contained with the development of an associated abscess cavity can often be successfully managed without surgery[27]. An excellent and clinically useful classification system for diverticular perforations was developed by Hinchey and colleagues and modified by others[19,27]. The treatment of gastrointestinal perforation includes fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, source control, organ system support, and nutrition. Antibiotics are standard treatment for gastrointestinal perforation[7,8,18,28-30]. Many efficacious regimens have been described, and no single agent or combination of agents has been found to be superior to the others[28-32]. We started Subacillin plus SABS initially at ER. Owing to a good response, we then shifted to Subacillin only in the ward.

The duration of antibiotic coverage is controversial[28,33]. Some authors advocate a standard treatment of 7 to 14 d, whereas others recommend continuing antibiotics until the WBC count has normalized and the patient is afebrile[28,30]. Current general consensus advocates antimicrobial therapy for 5 to 7 d if clinical signs of infection have resolved[28,33]. If the patient fails to improve or worsens during this period, the adequacy of source control or the appropriateness of antibiotic coverage must be questioned[28]. Our patient responded well to medical treatment. He was afebrile on the third day. WBC count had normalized on the fourth day. Clinical signs of infection were resolved after oral intake on the fourth day. After 5 d of intravenous Subacillin, the patient received 7 additional days of the oral antibiotic Soonmelt.

We found one recent case report of fish bone induced distal ileum micro-perforation which was spontaneously relieved one day after admission while awaiting surgical intervention[34]. There were two previous documented cases of hepatic abscess secondary to fish bone perforation that were successfully treated with medical therapy, because of contraindication for operation[35,36]. The impacted fish bone remains unchanged in the pylorus. The patient remained asymptomatic during the 18 mo of follow-up.

The clinical improvement is not necessarily a result of fish bone pass out. Because the fish bone is sharp and linear, it could penetrate the small intestinal wall and migrate into the surrounding soft tissue. It may cause delayed complications. Reported complications of migrated fish bones include retropharyngeal abscesses[37], gastric submucosal mass[38], inflammatory omentum mass[39], pancreatitis with intraluminal thrombosis of superior mesenteric vein due to penetrating into the superior mesenteric vein[40], migration into the right renal vein[41], and liver abscess[35,36,42-45]. Most complications following foreign body impaction will require surgery at some stage, even many years after ingestion has occurred[46]. Because there are vital organs nearby (such as the mediastinum, great vessel, liver and pancreas), fish bones migrated from the esophagus, stomach or duodenum may induce catastrophic complications. It is important to be mindful of the delayed complications of fish bones migration.

In conclusion, ingestion of foreign bodies is a common event. However, perforation of the GI tract by fish bones is not common. Key hints for the diagnosis of a fish bone induced GI tract perforation are the following: acute onset of peritonitis signs, patient’s dietary history with an emphasis on fish, and image evidence of abdominal CT. Key factors affecting clinical treatment decisions include the nature of perforation, the patient’s overall health condition, and the timing of diagnosis. Medical treatment may be one of the choices in micro-perforation of the distal ileum induced by fish bone in select patient.