Published online Nov 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i41.5918

Revised: May 10, 2012

Accepted: May 26, 2012

Published online: November 7, 2012

AIM: To investigate in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease the efficacy of symbiotics associated with a high-fibre diet on abdominal symptoms.

METHODS: This study was a multicentre, 6-mo randomized, controlled, parallel-group intervention with a preceding 4-wk washout period. Consecutive outpatients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease, aged 40-80 years, evaluated in 4 Gastroenterology Units, were enrolled. Symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease patients were randomized to two treatment arms A or B. Treatment A (n = 24 patients) received 1 symbiotic sachet Flortec© (Lactobacillus paracasei B21060) once daily plus high-fibre diet for 6 mo. Treatment B (n = 21 patients) received high-fibre diet alone for 6 mo. The primary endpoint was regression of abdominal symptoms and change of symptom severity after 3 and 6 mo of treatment.

RESULTS: In group A, the proportion of patients with abdominal pain < 24 h decreased from 100% at baseline to 35% and 25% after 3 and 6 mo, respectively (P < 0.001). In group B the proportion of patients with this symptom decreased from 90.5% at baseline to 61.9% and 38.1% after 3 and 6 mo, respectively (P = 0.001). Symptom improvement became statistically significant at 3 and 6 mo in group A and B, respectively.

The proportion of patients with abdominal pain >24 h decreased from 60% to 20% then 5% after 3 and 6 mo, respectively in group A (P < 0.001) and from 33.3% to 9.5% at both 3 and 6 mo in group B (P = 0.03). In group A the proportion of patients with abdominal bloating significantly decreased from 95% to 60% after 3 mo, and remained stable (65%) at 6-mo follow-up (P = 0.005) while in group B, no significant changes in abdominal bloating was observed (P = 0.11). After 6 mo of treatment, the mean visual analogic scale (VAS) values of both short-lasting abdominal pain (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 4.6 ± 2.1 vs 2.2 ± 0.8, P = 0.02; group B: 4.6 ± 2.9 vs 2.0 ± 1.9, P = 0.03) and abdominal bloating (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 5.3 ± 2.2 vs 3.0 ± 1.7, P = 0.005; group B: 5.3 ± 3.2 vs 2.3 ± 1.9, P = 0.006) decreased in both groups, whilst the VAS values of prolonged abdominal pain decreased in the Flortec© group, but remained unchanged in the high-fibre diet group (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 6.5 ± 1.5 vs 4.5 ± 2.1, P = 0.052; group B: 4.5 ± 3.8 vs 5.5 ± 3.5).

CONCLUSION: A high-fibre diet is effective in relieving abdominal symptoms in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. This treatment may be implemented by combining the high-fibre diet with Flortec©.

-

Citation: Lahner E, Esposito G, Zullo A, Hassan C, Cannaviello C, Paolo MCD, Pallotta L, Garbagna N, Grossi E, Annibale B. High-fibre diet and

Lactobacillus paracasei B21060 in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(41): 5918-5924 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i41/5918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i41.5918

Diverticular disease (DD) of the colon is a very common disorder which remains asymptomatic in nearly 80% of patients. The remaining patients develop recurrent abdominal symptoms and some complications, such as diverticulitis and bleeding, requiring hospital admission and surgery[1-3]. The main goals of symptomatic DD management are both relief of abdominal symptoms and prevention of acute diverticulitis[4].

The standard therapeutic approach for symptomatic uncomplicated DD still remains to be defined. Guidelines of the American College of Gastroenterology, the European Association for Endoscopy Surgery, and the World Gastroenterology Organization recommend a high-fibre diet in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD[5,6]. Some data would suggest that cyclic treatment with nonabsorbable antibiotics plus high-fibre diet is more effective in obtaining symptom relief as compared to diet alone[7,8], and it reduces the incidence of first episode of acute diverticulitis at 1 year[9]. However, the level of evidence of superiority of nonabsorbable antibiotics over dietary fibre or fibre supplementation is poor[10], and both the cost and efficacy of a long-life cyclic treatment with nonabsorbable antibiotics to prevent diverticulitis in all symptomatic DD patients has been questioned[11,12].

A recent systematic review suggest the potential usefulness of fibre, rifaximin, mesalazine, and probiotics, and their possible combination in symptomatic uncomplicated DD treatment, but reliable controlled therapeutic trials are still lacking[12].

Probiotics, prebiotics, and symbiotics may modify the gut microbial balance leading to health benefits[13-16]. Changes in peri-diverticular bacterial flora have been suggested as a potential key step in the pathogenesis of diverticular microscopic inflammation. This, in turn, may play a role in generating abdominal symptoms in uncomplicated DD, thus making probiotics an appealing therapy for DD. Some data suggest that probiotic therapy is safe and potentially useful in the management of DD patients[17]. Flortec© is a totally natural symbiotic agent, consisting of the synergistic combination of Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) B21060 (probiotic component) and arabinogalactan/xylooligosaccharides (prebiotic component). Flortec© treatment has been shown to be effective in relieving symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome[18], and in the treatment of acute diarrhea in adults treated at a primary care setting[19]. The therapeutic benefit of this symbiotic formulation in addition to a high dietary fibre intake in symptomatic uncomplicated DD remains to be defined. The primary aim of this cluster randomized study was to investigate the efficacy of a patented symbiotic preparation containing L. paracasei B21060 in association with high-fibre diet compared to high-fibre diet alone on relief of abdominal symptoms in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD.

Consecutive outpatients were evaluated in 4 Gastroenterology Units (1 academic and 3 nonacademic) for enrolment in the study. Inclusion criteria were a well-established diagnosis of symptomatic uncomplicated DD and age ranging from 40 to 80 years. The study was performed over a 10 mo period from March, 2010 to January, 2011.

Symptomatic uncomplicated DD was defined as the presence of colonic diverticula associated with abdominal pain and/or bloating for at least 6 mo before recruitment, without signs of acute diverticulitis[20]. Signs of acute inflammation were excluded by physical examination (to ascertain the absence of abdominal rigidity, rebound tenderness, and/or guarding in one or more abdominal quadrants), as well as routine biochemistry (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, protein electrophoresis). To quantify and localize the colonic diverticula, double contrast enema and/or colonoscopy was performed. Exclusion criteria were: presence of less than 5 diverticula, recent history (< 3 mo) or actual clinical evidence of acute diverticulitis, previous colonic surgery, antibiotics, mesalazine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or laxative use during the four weeks before enrolment, coexisting inflammatory bowel disease, diseases with possible small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Patients were also excluded if dyspeptic symptoms were predominant over abdominal symptoms and when low compliance or motivation could be expected for any reason. All patients provided written informed consent.

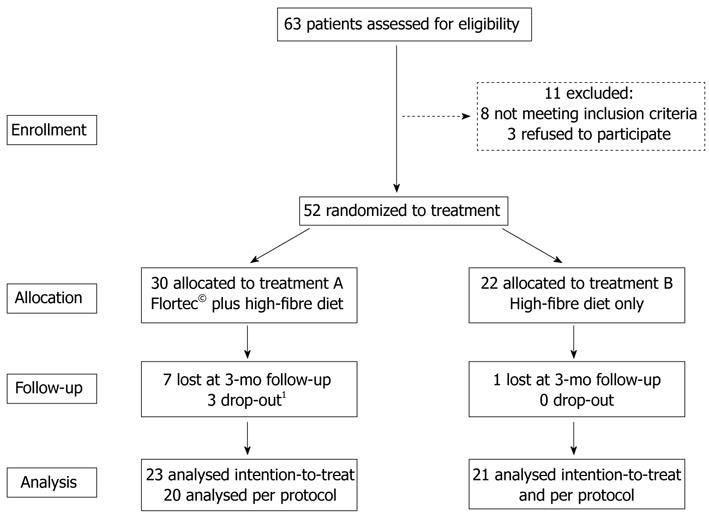

This study was a multicentre, 6-mo randomized, controlled, parallel-group intervention with a preceding 4-wk washout period. All patients were instructed to follow a high-fibre diet containing at least 30 g daily intake of dietary fibre as well as a daily water intake of at least 1.5 L. For this purpose, all patients were given an information sheet regarding the content of dietary fibre in commonly consumed fruits, vegetables and cereals, and dietary counselling was performed. According to cluster randomization[21], each participating centre was randomly assigned to recruit patients for either treatment A or B. For 6 mo, treatment arm A received a once daily dose of the symbiotic preparation Flortec© administered orally, plus high-fibre diet, while treatment arm B was treated with high-fibre diet only (Figure 1). Rescue medication was not allowed during the study period.

All patients underwent 3 clinical interviews: at study entry and after 3 and 6 mo of intervention. Patients were evaluated for abdominal symptoms, compliance to therapy assessed by a structured questionnaire, and routine biochemistry (complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, protein electrophoresis) was done to exclude signs of acute inflammation. In order to assess compliance to the high-fibre diet and to verify eventual changes in dietary fibre intake, at study entry and 3- and 6-mo follow-up clinical interviews, the daily fibre intake during the 7 d before the interview was recorded (a semiquantitative score ranging from 0-28 was used: for each day of the week max 4 points were assigned: 1 point for intake of fruit and another point for intake of vegetables or whole grain cereals at lunch and/or dinner). The primary endpoint considered was the regression of abdominal symptoms and change in symptom severity after 3 and 6 mo of treatment. As a secondary endpoint the tolerability of treatment - i.e., occurrence of adverse effects was considered.

Symptoms of patients were evaluated at study entry and after 3 and 6 mo of treatment by assessing the presence/absence and intensity of abdominal pain lasting more or less than 24 h and the presence/absence and intensity of abdominal bloating[19,21]. Patients were asked to grade the intensity of abdominal symptoms on a visual analogic scale (VAS) consisting of a 10 cm long line with 0 cm indicating “no sensation” and 10 cm indicating “the strongest sensation ever felt”.

Flortec© (Bracco Co, Milan, Italy) is a composite symbiotic formulation and each 7 g sachet contains 5 × 109 colony-forming units viable lyophilized L. paracasei B12060. The dry powder bacteria were mixed with the following excipients: xylo-oligosaccharides (700 mg), glutamine (500 mg), and arabinogalactone (1243 mg). As glutamine and oligosaccharides have some prebiotic activities on human fecal flora, the Flortec formulation combines the synergistic effect of a prebiotic with a probiotic (a symbiotic formulation). The study preparation was in powder form. Patients were instructed to store the preparation at room temperature (< 20 °C) in a dry place and to dissolve the powder preparation in 100 mL of water once daily and to ingest it immediately 2 h after lunch.

The sample size was calculated considering data reported in literature: we expected that dietary fibre supplementation would be effective in 30% of cases, accepting a range from 15% to 45% (5, 12) s Because the combined efficacy of high-fibre diet and symbiotic supplementation is not known in literature, for this pilot study a superiority of about 30% for the second treatment arm over the first one was supposed, and a total of 50 cases (25 for each arm) were needed, with an α error of 10% and a study power of 80%.

The analysis was carried out on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, defined as all randomized patients who performed at least one follow-up assessment after baseline, and on the per-protocol population, defined as all patients who completed the prescribed treatment in the 6-mo-treatment period. The presence of abdominal symptoms was expressed as number (%) of total patients and in terms of severity as mean ± SD of VAS. Data were analysed by Fisher’s exact and/or Student’s t-test. To test for differences between the baseline, 3- and 6-mo sets of proportion of patients presenting abdominal pain or bloating, Cochran’s Q test was performed. The results were coded 0 for absence and 1 for presence of abdominal symptoms. The compliance to high-dietary fibre intake was assessed by analysis of variance. The P values were considered significant if they were less than 0.05. The statistical analyses were carried out using a dedicated software package (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium, version 10.1.2).

Of the 52 randomized patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD (35 females, mean age 66.3 ± 9.5 years), at baseline 48 (92.3%) had abdominal pain lasting less than 24 h, 22 (42.3%) had abdominal pain lasting more than 24 h, and 42 (80.8%) had abdominal bloating, whereas dyspeptic symptoms were present in only 6 (11.5%) patients. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are given in Table 1. No differences between the treatment groups were observed with respect to baseline characteristics and gastrointestinal symptoms. The dietary fibre intake score was not statistically different between groups (13.3 ± 7.3 vs 16.0 ± 9.1, P = 0.30).

| High-fibre diet plus probiotics (n = 30) | High-fibre diet alone (n = 22) | P value | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yr | 68.1 ± 8.6 | 63.8 ± 10.3 | 0.10 |

| Gender, female | 22 (73.3) | 13 (59.1) | 0.43 |

| Body mass index | 26.4 ± 2.9 | 24.9 ± 2.9 | 0.07 |

| Smoking habit | 12 (40.0) | 11 (50.0) | 0.66 |

| Alcoholic drinks | 9 (30.0) | 11 (50.0) | 0.24 |

| Coffee | 28 (93.3) | 20 (90.9) | 0.84 |

| Localization of colon diverticula | |||

| Left colon | 27 (90.0) | 20 (90.9) | 0.49 |

| Left and right colon | 3 (10.0) | 2 (9.1) | 0.28 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Dyspeptic symptoms | 3 (10.0) | 3 (13.6) | 0.97 |

| Abdominal pain lasting < 24 h | 28 (93.3) | 20 (90.9) | 0.48 |

| VAS | 4.6 ± 2.2 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 0.97 |

| Abdominal pain lasting > 24 h | 14 (46.7) | 8 (36.4) | 0.49 |

| VAS | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 5.2 ± 2.8 | 0.12 |

| Abdominal bloating | 25 (83.3) | 17 (77.2) | 0.49 |

| VAS | 5.4 ± 2.2 | 5.2 ± 3.1 | 0.80 |

The flowchart in Figure 1 shows the progress of patients from recruitment until the end of the study. Of the 52 randomized patients, 30 (57.7%) were allocated to the Flortec© plus high-fibre diet group (group A) and 22 (42.3%) to the high-fibre diet group (group B). Eight patients were lost at 3-mo follow-up, and, therefore, 44 patients were included in the ITT population. In group A, 3 patients dropped out after 3 mo of treatment, 1 patient for new onset of constipation and 2 patients for worsening of abdominal symptoms, while in group B all 21 patients completed the 6-mo treatment period. Thus, the PP population consisted of 41 patients.

At baseline, 3- and 6-mo evaluation, the dietary fibre intake scores were not different between the Flortec© group and the high-fibre diet group. In particular, in group A patients, the dietary fibre intake score was 16 ± 9.1 at baseline (17.9 ± 7.3 vs 16 ± 9.1, P < 0.01 at 3 mo; 18.3 ± 7 vs 16 ± 9.1, P < 0.01 at 6 mo). In group B patients, this score increased from 13.3 ± 7.3 at baseline to 18.4 ± 6.1 at 3 mo (P < 0.0001) and to 21.4 ± 4.5 at 6 mo (P < 0.0001). Dietary fibre intake similarly increased in both groups over the study period (P = 0.702).

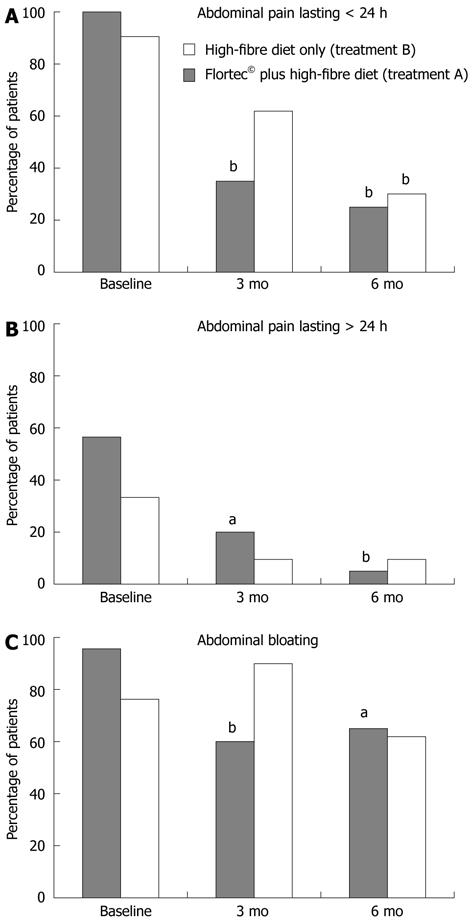

As shown in Figure 2, in group A the proportion of patients with abdominal pain lasting less than 24 h significantly decreased from 100% at baseline to 35% after 3 mo and to 25% after 6 mo of treatment (P < 0.001 by Cochran’s Q test). In group B the proportion of patients with this symptom decreased from 90.5% at baseline to 61.9% after 3 mo and to 38.1% after 6 mo of treatment (P = 0.001 by Cochran’s Q test). The symptom improvement became statistically significant at 3 and 6 mo in groups A and B, respectively.

In group A, the proportion of patients with abdominal pain lasting more than 24 h (Figure 2) significantly decreased from 60% at baseline to 20% after 3 mo and further decreased to 5% after 6 mo of treatment (P < 0.001 by Cochran’s Q test). In group B, the proportion of patients with prolonged abdominal pain significantly decreased from 33.3% at baseline to 9.5% after 3 mo, and remained stable (9.5%) at 6-mo follow-up (P = 0.03 by Cochran’s Q test).

As shown in Figure 2, in group A the proportion of patients with abdominal bloating significantly decreased from 95% to 60% after 3 mo, and remained stable (65%) at 6-mo follow-up (P = 0.005 by Cochran’s Q test). In group B, no significant changes in abdominal bloating was observed, the proportion of patients complaining such a symptom being 76.2%, 80.9%, and 61.9% at entry, 3-, and 6-mo follow-up, respectively (P = 0.11 by Cochran’s Q test).

In the high-fibre diet group, 3 patients described the new onset of abdominal symptoms during the study period; 1 patient experienced prolonged abdominal pain and 2 patients abdominal bloating, whilst no onset of new symptoms occurred in the Flortec© group.

After 6 mo of treatment, the mean VAS values of both short-lasting abdominal pain (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 4.6 ± 2.1 vs 2.2 ± 0.8, P = 0.02; group B: 4.6 ± 2.9 vs 2.0 ± 1.9, P = 0.03) and abdominal bloating (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 5.3 ± 2.2 vs 3.0 ± 1.7, P = 0.005; group B: 5.3 ± 3.2 vs 2.3 ± 1.9, P = 0.006) decreased in both groups, whilst the VAS values of prolonged abdominal pain decreased in the Flortec© group, but remained unchanged in the high-fibre diet group (VAS, mean ± SD, group A: 6.5 ± 1.5 vs 4.5 ± 2.1, P = 0.052; group B: 4.5 ± 3.8 vs 5.5 ± 3.5).

None of the patients developed altered biochemical inflammatory parameters, acute diverticulitis or other diverticular disease complications throughout the 6-mo study period. In both groups no adverse event was registered over the 6-mo treatment period.

High-fibre diet is largely suggested for symptomatic uncomplicated DD patients[5,6]. Probiotic therapy may be of benefit in DD patients, but its efficacy when combined with high-fibre diet remains to be established. This pilot study investigated the efficacy of a continuous 6-mo treatment with a symbiotic preparation containing L. paracasei B21060 associated with a high-fibre diet compared to a high-fibre diet alone in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD. The main findings of this study were that (1) a high-fibre diet alone is effective on some abdominal symptoms of symptomatic uncomplicated DD patients, but the combination of this approach with a symbiotic preparation containing L. paracasei B21060 allows an increase in the therapeutic response; and (2) the prescription of a high-fibre diet increases the intake of dietary fibre over time, regardless of whether a single diet or combined approach with symbiotic supplementation is used.

In detail, the high-fibre diet alone was effective in reducing short-lasting abdominal pain following 6 mo of treatment, but using the combined approach with Flortec© a regression of this symptom was already observed after 3 mo. With the dietary approach alone regression of prolonged abdominal pain was observed (P = 0.03), but this therapeutic response was more accentuated with the combined treatment strategy. Finally, abdominal bloating significantly regressed only with the symbiotic treatment, while high-fibre diet alone had no beneficial effect on this symptom. Taken together, these findings show that the combined approach offers an advantage over the dietary approach alone in improving the therapeutic response of patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD with regard to abdominal symptoms.

Our study also showed that both groups significantly increased dietary fibre intake over the study period. This result may be explained by the fact that according to our study design the prescription of a high-fibre diet was supported by a dietary information sheet and followed over time by registering an intake score. It is likely that this systematic approach may have increased the intake of dietary fibre over time, perhaps due to an increased awareness that the prescription of diet needs to be taken seriously, like a real treatment option and not as a simple suggestion.

To date, the underlying mechanisms of the therapeutic benefit of dietary fibre in diverticular disease are not fully understood, albeit a relationship with stool volume and transit time has been hypothesized[5,22]. More recently, it has been shown that vegetarians are less likely than non-vegetarians to have radiologically confirmed diverticulosis (12% vs 33%), and that the insoluble component of fibre is associated with a decreased risk (relative risk 0.63, 95%CI: 0.36 to 0.75) of DD[23], thus giving an indirect rationale for the high-fibre diet in symptomatic uncomplicated DD.

However, abdominal bloating was not effectively treated with a high-fibre diet, but a good therapeutic response was obtained in the Flortec© group only. This result is not surprising because it is well known that a high-fibre diet may increase the presence of intestinal gas due to an increase in the gas-producing intestinal microflora[24]. Indeed, among our study population, it was only in the high-fibre diet group that patients with a new onset of abdominal bloating during the study period were registered.

The rationale for the use of probiotics in symptomatic uncomplicated DD is given by their antiinflamnatory effects and capability to enhance anti-infective defences by (1) maintaining an adequate bacterial colonization in the gastrointestinal tract; (2) inhibiting colonic bacterial overgrowth and metabolism of pathogens; and (3) reducing proinflammatory cytokines[13,14]. In DD, local alterations of the peridiverticular colonic flora have been included as one of the causes leading to periods of symptomatic disease[1-3]. Thus, the therapeutic benefit of the supplementation of L. paracasei B21060 observed in our study may be explained by the ability of probiotics to ensure an optimal colonic microenvironment, which is probably able to prevent local diverticular inflammation and to reduce abdominal symptoms. This idea is supported by experimental data showing that L. paracasei is able to survive the passage through the gastrointestinal tract, to persist in stools after administration is discontinued, and to temporarily associate throughout different sites of the entire human colon, suggesting a positive ecological role played by this probiotic strain[25,26].

Literature data on the role of probiotics in the management of DD are still scant. The benefit of a cyclic 6-mo supplementation with a L. paracasei sub. paracasei F19 in association with a high-fibre diet on prolonged abdominal pain and bloating in symptomatic uncomplicated DD has been described, while the high-fibre diet alone appeared to be ineffective[19]. Compared to the current study, in this study the prescription of a high-fibre diet was not accompanied by detailed dietary information and compliance to the high-fibre diet was not assessed, thus making it difficult to evaluate the therapeutic response in this treatment arm. Other previous studies investigated the efficacy of probiotics, as a non-pathogenic Escherichia coli strain or Lactobacillus casei and VSL#3 together with other therapeutic agents such as antibiotics or mesalazine in patients with DD[27-31], making the results of these studies not comparable with our findings.

We are aware that the relative low sample size of this pilot study may have limited the statistical power of results. However, we preferred to analyse data with respect to single abdominal symptoms rather than to a global symptom score, thus further reducing the sample number. But in this way, the efficacy of treatment on each single symptom could be evaluated more accurately. Furthermore, in this study two treatment arms were compared without a true control and cluster randomization was performed, thus limiting the interpretation of the results with particular regard to placebo effect. Considering that symptoms in symptomatic uncomplicated DD are likely to be influenced by the placebo effect, a placebo-controlled study is necessary to confirm our results.

To conclude, this study provides evidence that a high-fibre diet alone is effective in relieving abdominal pain in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD. This therapeutic response may be implemented by combining the dietary approach with Flortec© treatment which is effective in abdominal bloating, too. Data from this pilot study need to be confirmed in other larger trials.

The standard therapeutic approach for symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (DD) still remains to be defined. Guidelines of American and European Gastroenterology Associations recommend a high-fibre diet in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD. A recent systematic review suggests the potential usefulness of fibre, rifaximin, mesalazine, and probiotics, and their possible combination in symptomatic uncomplicated DD treatment, but reliable controlled therapeutic trials are still lacking.

Probiotics, prebiotics, and symbiotics may modify the gut microbial balance and changes in peri-diverticular bacterial flora likely play a role in the pathogenesis of diverticular microscopic inflammation and in generating abdominal symptoms in uncomplicated DD. Probiotic therapy is safe and potentially useful in the management of DD patients. Flortec© is a totally natural symbiotic agent, consisting of the synergistic combination of Lactobacillus paracasei (L. paracasei) B21060 (probiotic component) and arabinogalactan/xylooligosaccharides (prebiotic component), shown to be effective in relieving symptoms associated with irritable bowel syndrome and acute diarrhea. The therapeutic benefit of a symbiotic formulation in addition to a high dietary fibre intake in symptomatic uncomplicated DD remains to be defined.

In this study, for the first time the efficacy of a symbiotic formulation in addition to a high dietary fibre intake in symptomatic uncomplicated DD is investigated. All patients were instructed to follow a high-fibre diet containing at least 30 g daily intake of dietary fibre as well as a daily water intake of at least 1.5 L. For this purpose, all patients were given an information sheet regarding the content of dietary fibre in commonly consumed fruits, vegetables and cereals, and dietary counselling was performed.

The high-fibre diet alone is effective in relieving abdominal pain in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated DD. Adherence to diet should be monitored by dietary counselling. The combination of the high-fibre diet with a symbiotic preparation may improve the therapeutic response. Data of this pilot study need to be confirmed in other larger, placebo-controlled trials.

Colonic diverticula is a wide-ranging condition running the spectrum from a symptomless to a severe, chronic, recurrent disorder, and has been classified in four clinical stages: (1) the development of diverticula (stage 1); (2) the symptom-free stage (stage 2); (3) the symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (stage 3); and (4) the complicated diverticular disease (stage 4). Symbiotics are the synergistic combination of a probiotic component, as for example L. paracasei B21060, and a prebiotic component, as for example arabinogalactan and/or xylooligosaccharides.

The article demonstrates that the combination of high-fibre diet and L. paracasei B21060 can relieve abdominal bloating as well as abdominal pain. The result is interesting and suggests that a high-fibre diet is effective in relieving abdominal symptoms in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease. This treatment may be implemented by combining a high-fibre diet with Flortec©.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Nobuyuki Matsuhashi, NTT Medical Center Tokyo, 5-9-22 Higashi-gotanda, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-8625, Japan; Antonio Basoli, Professor, General Surgery “Paride Stefanini”, Università di Roma-Sapienza, Viale del Policlinico 155, 00161 Roma, Italy; Dr. Naoki Ishii, Department of Gastroenterology, St. Luke’s In, 9-1 Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Parra-Blanco A. Colonic diverticular disease: pathophysiology and clinical picture. Digestion. 2006;73 Suppl 1:47-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stollman N, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. Lancet. 2004;363:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sheth AA, Longo W, Floch MH. Diverticular disease and diverticulitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1550-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ludeman L, Warren BF, Shepherd NA. The pathology of diverticular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:543-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ünlü C, Daniels L, Vrouenraets BC, Boermeester MA. A systematic review of high-fibre dietary therapy in diverticular disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:419-427. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Stollman NH, Raskin JB. Diagnosis and management of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad Hoc Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3110-3121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Latella G, Pimpo MT, Sottili S, Zippi M, Viscido A, Chiaramonte M, Frieri G. Rifaximin improves symptoms of acquired uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Colecchia A, Vestito A, Pasqui F, Mazzella G, Roda E, Pistoia F, Brandimarte G, Festi D. Efficacy of long term cyclic administration of the poorly absorbed antibiotic Rifaximin in symptomatic, uncomplicated colonic diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:264-269. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Bianchi M, Festa V, Moretti A, Ciaco A, Mangone M, Tornatore V, Dezi A, Luchetti R, De Pascalis B, Papi C. Meta-analysis: long-term therapy with rifaximin in the management of uncomplicated diverticular disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:902-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Humes D, Smith JK, Spiller RC. Colonic diverticular disease. Clin Evid (. Online). 2011;2011:pii0405. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Maconi G, Manes G, Tammaro G, De Francesco V, Annibale B, Ficano L, Buri L, Gatto G. Cyclic antibiotic therapy for diverticular disease: a critical reappraisal. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:295-302. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Maconi G, Barbara G, Bosetti C, Cuomo R, Annibale B. Treatment of diverticular disease of the colon and prevention of acute diverticulitis: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1326-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sanders ME. Probiotics: definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46 Suppl 2:S58-61; discussion S144-151. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sullivan A, Nord CE. Probiotics and gastrointestinal diseases. J Intern Med. 2005;257:78-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gill HS. Probiotics to enhance anti-infective defences in the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:755-773. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Brandt LJ, Quigley EM. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut. 2010;59:325-332. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Narula N, Marshall JK. Role of probiotics in management of diverticular disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1827-1830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andriulli A, Neri M, Loguercio C, Terreni N, Merla A, Cardarella MP, Federico A, Chilovi F, Milandri GL, De Bona M. Clinical trial on the efficacy of a new symbiotic formulation, Flortec, in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a multicenter, randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42 Suppl 3 Pt 2:S218-S223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Grossi E, Buresta R, Abbiati R, Cerutti R. Clinical trial on the efficacy of a new symbiotic formulation, Flortec, in patients with acute diarrhea: a multicenter, randomized study in primary care. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44 Suppl 1:S35-S41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Annibale B, Maconi G, Lahner E, De Giorgi F, Cuomo R. Efficacy of Lactobacillus paracasei sub. paracasei F19 on abdominal symptoms in patients with symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease: a pilot study. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2011;57:13-22. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Murphy AW, Esterman A, Pilotto LS. Cluster randomized controlled trials in primary care: an introduction. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12:70-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Simpson J, Neal KR, Scholefield JH, Spiller RC. Patterns of pain in diverticular disease and the influence of acute diverticulitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1005-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Burkitt DP, Walker AR, Painter NS. Effect of dietary fibre on stools and the transit-times, and its role in the causation of disease. Lancet. 1972;2:1408-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 541] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Humes DJ, West J. Diet and risk of diverticular disease. BMJ. 2011;343:d4115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zuckerman MJ. The role of fiber in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: therapeutic recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:104-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Morelli L, Zonenschain D, Callegari ML, Grossi E, Maisano F, Fusillo M. Assessment of a new synbiotic preparation in healthy volunteers: survival, persistence of probiotic strains and its effect on the indigenous flora. Nutr J. 2003;2:11. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Morelli L, Garbagna N, Rizzello F, Zonenschain D, Grossi E. In vivo association to human colon of Lactobacillus paracasei B21060: map from biopsies. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:894-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fric P, Zavoral M. The effect of non-pathogenic Escherichia coli in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:313-315. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Elisei W. Mesalazine and/or Lactobacillus casei in preventing recurrence of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon: a prospective, randomized, open-label study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Elisei W, Aiello F. Balsalazide and/or high-potency probiotic mixture (VSL#3) in maintaining remission after attack of acute, uncomplicated diverticulitis of the colon. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1103-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Elisei W. Mesalazine and/or Lactobacillus casei in maintaining long-term remission of symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:916-920. [PubMed] |