Published online Oct 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5807

Revised: June 27, 2012

Accepted: July 9, 2012

Published online: October 28, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the status of anorectal function after repeated transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM).

METHODS: Twenty-one patients undergoing subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis were included. There were more than 5 large (> 1 cm) polyps in the remaining rectum (range: 6-20 cm from the anal edge). All patients, 19 with villous adenomas and 2 with low-grade adenocarcinomas, underwent TEM with submucosal endoscopic excision at least twice between 2005 and 2011. Anorectal manometry and a questionnaire about incontinence were carried out at week 1 before operation, and at weeks 2 and 3 and 6 mo after the last operation. Anal resting pressure, maximum squeeze pressure, maximum tolerable volume (MTV) and rectoanal inhibitory reflexes (RAIR) were recorded. The integrity and thickness of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and external anal sphincter (EAS) were also evaluated by endoanal ultrasonography. We determined the physical and mental health status with SF-36 score to assess the effect of multiple TEM on patient quality of life (QoL).

RESULTS: All patients answered the questionnaire. Apart from negative RAIR in 4 patients, all of the anorectal manometric values in the 21 patients were normal before operation. Mean anal resting pressure decreased from 38 ± 5 mmHg to 19 ± 3 mmHg (38 ± 5 mmHg vs 19 ± 3 mmHg, P = 0.000) and MTV from 165 ± 19 mL to 60 ± 11 mL (165 ± 19 mL vs 60 ± 11 mL, P = 0.000) at month 3 after surgery. Anal resting pressure and MTV were 37 ± 5 mmHg (38 ± 5 mmHg vs 37 ± 5 mmHg, P = 0.057) and 159 ± 19 mL (165 ± 19 mL vs 159 ± 19 mL, P = 0.071), respectively, at month 6 after TEM. Maximal squeeze pressure decreased from 171 ± 19 mmHg to 62 ± 12 mmHg (171 ± 19 mmHg vs 62 ± 12 mmHg, P = 0.000) at week 2 after operation, and returned to normal values by postoperative month 3 (171 ± 19 vs 166 ± 18, P = 0.051). RAIR were absent in 4 patients preoperatively and in 12 (χ2 = 4.947, P = 0.026) patients at month 3 after surgery. RAIR was absent only in 5 patients at postoperative month 6 (χ2 = 0.141, P = 0.707). Endosonography demonstrated that IAS disruption occurred in 8 patients, and 6 patients had temporary incontinence to flatus that was normalized by postoperative month 3. IAS thickness decreased from 1.9 ± 0.6 mm preoperatively to 1.3 ± 0.4 mm (1.9 ± 0.6 mm vs 1.3 ± 0.4 mm, P = 0.000) at postoperative month 3 and increased to 1.8 ± 0.5 mm (1.9 ± 0.6 mm vs 1.8 ± 0.5 mm, P = 0.239) at postoperative month 6. EAS thickness decreased from 3.7 ± 0.6 mm preoperatively to 3.5 ± 0.3 mm (3.7 ± 0.6 mm vs 3.5 ± 0.3 mm, P = 0.510) at month 3 and then increased to 3.6 ± 0.4 mm (3.7 ± 0.6 mm vs 3.6 ± 0.4 mm, P = 0.123) at month 6 after operation. Most patients had frequent stools per day and relatively high Wexner scores in a short time period. While actual fecal incontinence was exceptional, episodes of soiling were reported by 3 patients. With regard to the QoL, the physical and mental health status scores (SF-36) were 56.1 and 46.2 (50 in the general population), respectively.

CONCLUSION: The anorectal function after repeated TEM is preserved. Multiple TEM procedures are useful for resection of multi-polyps in the remaining rectum.

- Citation: Zhang HW, Han XD, Wang Y, Zhang P, Jin ZM. Anorectal functional outcome after repeated transanal endoscopic microsurgery. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(40): 5807-5811

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i40/5807.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5807

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant disease that is classically characterized by the development of hundreds to thousands of adenomas in the rectum and colon during the second decade of life. Almost all patients will develop colorectal cancer if they are not identified and treated at an early stage. The incidence of FAP at birth is approximately 1/8300[1] in both men and women, and less than 1% of them develop colorectal cancer[1].

Twenty years ago, many patients with FAP underwent subtotal colectomy in China. Currently, some of the older patients refused to undergo a complicated operation (such as ileal pouch-anal anastomosis) because of old age or poor physical status. However, polyps are still present in the remaining rectum of patients and some of these polyps are too large to be extirpated by a colonoscope. These large polyps often cause bleeding and discomfort in old patients and anxiety about the risk of cancer in relatively younger patients. These patients desire a minimally invasive procedure.

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) was developed in 1983 by Büess et al[2-6]. It is a minimally invasive procedure to manage anorectal villous adenomas and early rectal adenocarcinomas[7,8]. TEM can be used to excise tumors located in the middle and upper rectum, and to manage other lesions, such as adenomas, which are not amenable to colonoscopic excision and can spare some patients the risks and side effects of major rectal surgery. In this study, patients had several large polyps and many small polyps. We performed TEM repeatedly to excise large polyps and fulgerize small polyps. The patients were satisfied with the clinical and anorectal functional outcome after TEM.

Generally, several factors from a single TEM procedure may cause internal anal sphincter (IAS) damage, which results in a decrease in mean anal resting pressure (ARP) and absence of rectoanal inhibitory reflexes (RAIR)[9]. It is unknown if repeated TEM will cause more severe IAS damage than a single TEM. The current study assessed anorectal function by anorectal manometry. Anorectal manometry provides objective data, which are necessary to determine sphincter function postoperatively.

From January 2005 to June 2011, 21 patients (13 females and 8 males) who had been diagnosed with FAP and underwent TEM 2 or 3 times were included in the study. All the patients had undergone subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis previously. When there were more than 5 large (> 1 cm) polyps in the remaining rectum (range: 6-20 cm from the anal edge), including 19 villous adenomas and 2 adenocarcinomas (2 uT1N0M0), these patients underwent TEM at least twice (19 underwent TEM twice and 2 underwent TEM 3 times) in our department using the technique designed by Buess et al[2,10].

All these patients were followed up for more than 6 mo (range: 6-24 mo). The median age of these patients at the time of the operation was 66 years (range: 49-82 years). All of the 21 patients underwent colonoscopy, biopsy and anorectal manometry before operation, and 2 patients with malignant lesions underwent endosonography and magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative staging. The inclusion criteria for this study were: those patients who had documentation for TEM, with villous adenomas, and uT1N0M0 adenocarcinomas located 5-18 cm from the anal verge. The exclusion criteria were preoperative defects of IAS as shown by endosonography or preoperational anal incontinence.

For patients with benign or low-grade malignant polyps in the remaining rectum, we performed submucosal endoscopic excision with TEM. Intraoperative pathological examination was performed to ensure that no malignant lesion remained. We closed the defect with sutures for the large polyps (> 1 cm).

There are a variety of approaches for anorectal manometry and determining RAIR. In our study, anorectal manometry was performed with an 8-channel water-perfused catheter (MMS Corporation, Holland) with an external diameter of 5.5 mm. A computer system with menu-driven software (MMS Corporation, Holland) was used. The patients assumed the left lateral decubitus position. The stationary technique (the catheter was left in one position) was used in our laboratory. Anorectal manometric parameters, such as ARP, maximum squeeze pressure (MSP), maximum tolerable volume (MTV) and RAIR were recorded. Endoanal ultrasonography was used to study the integrity and thickness of the IAS and external anal sphincter (EAS). Manometry and a standardized questionnaire about incontinence were carried out at preoperative week 1 and postoperative week 2, months 3 and 6.

We used the SF-36 score, which summarizes physical and mental health status, to assess the effect of multiple TEM on patient quality of life (QoL).

SPSS 17.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Paired Student’s t test was used to analyze the manometric data.

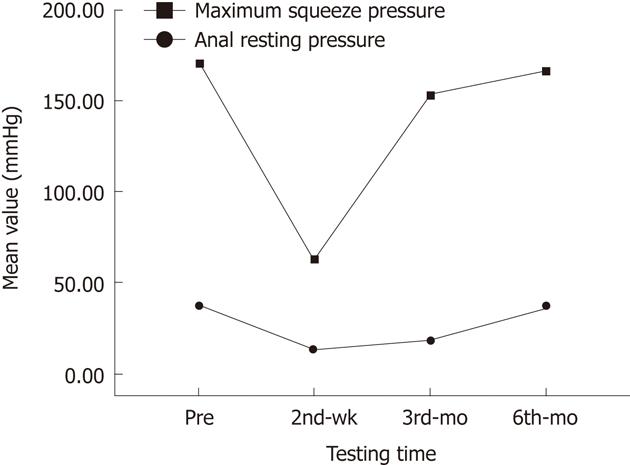

Apart from negative RAIR in 4 patients, all of the anorectal manometric values in the 21 patients were normal before the operation. However, all anorectal manometric parameters changed to different degrees after TEM. The mean ARP decreased from 38 mmHg ± 5 mmHg to 19 ± 3 mmHg (38 ± 5 mmHg vs 19 ± 3 mmHg, P = 0.000) and MTV decreased from 165 ± 19 mL to 60 ± 11 mL (165 ± 19 mL vs 60 ± 11 mL, P = 0.000) at month 3 after TEM. MSP decreased from 171 ± 19 mmHg to 62± 12 mmHg (171 ± 19 mmHg vs 62 ± 12 mmHg, P = 0.000) at week 2 after operation, and returned to normal values at postoperative month 3 (171 ± 19 vs 166 ± 18, P = 0.051). ARP and MTV were 37 ± 5 mmHg (38 ± 5 mmHg vs 37 ± 5 mmHg, P = 0.057) and 159 ± 19 mL (165 ± 19 mL vs 159 ± 19 mL, P = 0.071), respectively, at month 6 after TEM, which were up to the normal values (Figure 1). Among them, ARP in 18 patients, MSP in 19 patients and MTV in 21 patients were decreased by more than 50% at wk 2 after TEM (Table 1).

RAIR was absent in 4 patients preoperatively and in 12 (χ2 = 4.947, P = 0.026) patients at 3 mo after surgery while RAIR was absent only in 5 patients (including 4 patients whose RAIR was absent preoperatively) at postoperative month 6 (χ2 = 0.141, P = 0.707).

Endosonography demonstrated that disruption to the IAS occurred in 8 patients, with full integrity of the EAS in all patients. Of these 8 patients, 6 had incontinence to flatus at postoperative week 2, which disappeared at postoperative month 3. IAS thickness decreased from 1.9 ± 0.6 mm preoperatively to 1.3 ± 0.4 mm (1.9 ± 0.6 mm vs 1.3 ± 0.4 mm, P = 0.000) at postoperative month 3 and increased to 1.8 ± 0.5 mm (1.9 ± 0.6 mm vs 1.8 ± 0.5 mm, P = 0.239) at postoperative month 6. EAS thickness decreased from 3.7 ± 0.6 mm preoperatively to 3.5 ± 0.3 mm (3.7 ± 0.6 mm vs 3.5 ± 0.3 mm, P = 0.510) at month 3 and then increased 3.6± 0.4 mm (3.7 ± 0.6 mm vs 3.6 ± 0.4 mm, P = 0.123) at month 6, as demonstrated by endoanal ultrasonography.

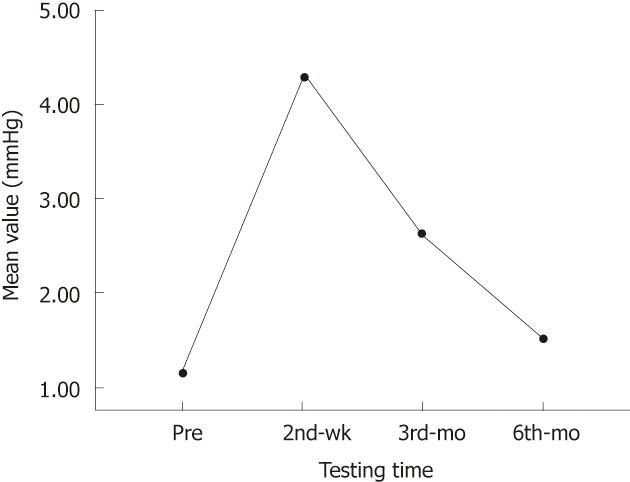

Twenty patients had frequent stools per day and relatively high Wexner scores in a short time period after repeated TEM. Two-thirds of the patients had more than 5 bowel movements per day and 1 bowel movement at night. Bowel movements almost returned to the preoperative frequency in 17 of these patients 3-6 mo after surgery. Actual fecal incontinence was uncommon, but episodes of soiling were reported by 3 patients. Overall, the number of stools per day increased from 1.5 ± 0.7 before surgery to 5.6 ± 1.8 (1.5 ± 0.7 vs 5.6 ± 1.8, P = 0.000) at postoperative week 2 and then decreased to 1.7 ± 0.7 (1.5 ± 0.7 vs 1.7 ± 0.7, P = 0.329) at postoperative month 6. The Wexner scores increased from 0 before surgery to 4.1 ± 0.8 (0 vs 4.1 ± 0.8, P = 0.000) at postoperative week 2, and then they decreased to 2.0 ± 0.5 (0 vs 2.0 ± 0.5, P = 0.002) and 0.7 ± 0.1 (0 vs 0.7 ± 0.1, P = 0.261) at postoperative mos 3 and 6, respectively (Figure 2).

With regard to the QoL of the patients, the 2 scores of the SF-36, which summarizes the physical and mental health status, were 56.1 ± 6.1 and 46.2 ± 5.9, respectively (both are 50 in the general population). The scores were not significantly different compared with the general population.

All the patients were followed up for 6-24 mo, and no case of relapse was found.

FAP is a genetic disorder that results from a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis gene. In the majority of patients, polyps arise during childhood, mostly in the distal colon (rectosigmoid) as small intramucosal nodules. At adolescence, the polyps are usually identified throughout the colon and, thereafter, increase in size and number. Approximately half of FAP patients develop adenomas by 15 years of age and 95% develop by 35 years.

Given the substantial risk of rectal cancer developing after colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis, total proctocolectomy was recommended mostly for the typical FAP patients with multiple rectal adenomas. Currently, surgical options for FAP include subtotal colectomy with IRA, total proctocolectomy with ileostomy, and proctocolectomy with or without mucosectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis.

Therefore, TEM has gradually been accepted. TEM is a new technique used only in a few well-known hospitals in China, and excellent outcome in morbidity and a low relapse rate have been achieved. A few studies have addressed its functional results[11-17] and suggest that several factors during a single TEM may cause IAS damage. This damage results in a decrease in mean ARP and absence of RAIR[9]. There have been no studies on clinical and anorectal functional results after repeated TEM. It is unknown whether repeated TEM causes more severe IAS damage.

Several studies have shown that the IAS is the main contributor to ARP[18-20]. Division or damage of the IAS may be associated with troublesome soiling[21] and accounts for approximately 50%-85% of ARP, and EAS contributes to the other 25%-30% of ARP[22-24]. On the other hand, MSP is largely related to contraction of the EAS. Use of a wide rectoscope during TEM may result in rupture of the IAS because of significant anal dilatation, followed by a temporary decrease in ARP and MSP.

A fall in anorectal pressures because of anal dilatation can occur after using anal separators and stapling instruments in coloproctological procedures for hemorrhoids, fistula, or cancer[25-27]. According to our study results, the decrease in sphincteric thickness at postoperative month 3 due to anal dilatation may be another factor contributing to a temporary fall in anorectal pressure. Both ARP and MSP were decreased at postoperative week 2. However, MSP turned normal at postoperative month 3, which was faster than that of ARP and MTV at postoperative month 6. The integrity of both EAS and IAS could be explained by the finding that patients were continent, even though ARP and MSP were decreased in a short time period after surgery. Six of 8 patients with rupture of the IAS in our study presented with some degree of incontinence. We consider that a damaged IAS may result in temporary incontinence. MTV was decreased at postoperative week 2 and was returned to normal at postoperative month 6. Partial excision and reconstruction of the anorectal wall during TEM resulted in a decrease in anorectal volume and compliance, which may lead to a decrease in MTV.

RAIR is defined as transient relaxation of the IAS in response to rectal distension as confirmed by Denny-Brown and Robertson[28]. RAIR has been postulated as a factor in maintenance of continence[29,30], but the exact role of RAIR is unknown. Therefore, the upper anal canal is able to discriminate between flatus and fecal material. It is absent initially after low anterior resection and the ileoanal pouch procedure. Regeneration may occur after hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis and low stapled anastomosis[31-34]. RAIR disappears when the anorectal wall is removed[35] and when there are changes with depth if the IAS is excised[10]. According to our study results, RAIR was absent in 4 patients preoperatively and absent in only 5 patients (including the 4 patients whose RAIR was absent preoperatively) at postoperative month 6. Patients whose RAIR was absent after TEM had a deeper IAS excision. Only one patient (excluding the 4 patients whose RAIR was absent preoperatively) whose RAIR was absent postoperatively was treated with TEM 3 times and the excision of the anorectal wall was deeper.

We used the Wexner score to assess continence[36]. Most patients had more frequent stools per day (15 patients had more than 5 bowel movements per day and 1 bowel movement at night) and relatively higher Wexner scores (range: 6-13) at postoperative week 2 after multiple TEMs. There was remarkable improvement in these incontinence scores at 6 mo after operation, with most patients reporting satisfactory anorectal function. While actual fecal incontinence was unusual, episodes of soiling were reported by 3 patients.

With regard to the QoL of patients who had multiple TEM procedures, at 6 mo after operation, the physical and mental health status scores were not significant compared with the general population. The FAPs, multiple-operations, postoperative discomfort were possible explanations for the low mental health status scores. A good QoL is a surrogate for good functional outcome. In the current study, anorectal function was well-preserved, even though some anorectal manometric parameters changed over time.

In conclusion, we found that anorectal function is well-preserved when TEM is performed repeatedly and patients have a good QoL. Repeated TEM is a good choice of treatment for resection of multi-polyps in the remaining rectum of FAP patients who underwent subtotal colectomy.

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) can cause colorectal cancer. Some of the patients with FAP who underwent subtotal colectomy in China twenty years ago refuse to undergo a complicated operation because of old age or poor physical status. The authors have used transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) repeatedly to excise large polyps and fulgerize small polyps for preventing the canceration of the disease.

TEM has been suggested as a minimally invasive procedure to manage anorectal villous adenomas and early rectal adenocarcinomas. However, TEM procedure may cause internal anal sphincter (IAS) damage. It is unknown if several procedures of TEM cause more severe IAS damage than a single TEM. There had been no studies on clinical and anorectal functional outcome after repeated TEM.

It is unknown whether TEM that is performed multiple times causes more severe IAS damage. This is the first study to report that repeated TEM is a good choice of treatment for resection of multi-polyps in the remaining rectum of FAP patients who undergo subtotal colectomy. Furthermore, the study showed that a good anoretal functional outcome with little IAS damage was achieved after repeated TEM.

Repeated TEM is a good choice of treatment for resection of multi-polyps in the remaining rectum of FAP patients who underwent subtotal colectomy.

This is a clinical report on anorectal function measured before and 2 to 3 after TEM excision of recurrent polyps in the rectal stump of FAP patients who underwent subtotal colectomy. This is a very interesting article which evaluates the short and long-term anorectal function (as measured by anorectal manometry) following repeat TEM procedures. TEM is very helpful tool in the management of recurrent polyps in FAP patients who have a residual rectal stump. There is little data on its use in this clinical setting, and no data on the impact of serial TEM procedures on anorectal function, so this work is important.

Peer reviewers: Michael Leitman, MD, FACS, Chief of General Surgery, Beth Israel Medical Center, 10 Union Square East, Suite 2M, New York, NY 10003, United States; Patricia Sylla, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Division of General and Colorectal Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, WACC 460, 15 Parkman Street, Boston, MA 02114, United States; Dr. Marek Bebenek, MD, PhD, Department of Surgical Oncology, Regional Comprehensive Cancer Center, pl. Hirszfelda 12, 53-413 Wroclaw, Poland

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Buess G, Hutterer F, Theiss J, Böbel M, Isselhard W, Pichlmaier H. [A system for a transanal endoscopic rectum operation]. Chirurg. 1984;55:677-680. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Buess G, Theiss R, Günther M, Hutterer F, Pichlmaier H. Endoscopic surgery in the rectum. Endoscopy. 1985;17:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Buess G, Kipfmüller K, Naruhn M, Braunstein S, Junginger T. Endoscopic microsurgery of rectal tumors. Endoscopy. 1987;19 Suppl 1:38-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Buess G, Kipfmüller K, Ibald R, Heintz A, Hack D, Braunstein S, Gabbert H, Junginger T. Clinical results of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:245-250. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Buess G, Kipfmüller K, Hack D, Grüssner R, Heintz A, Junginger T. Technique of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:71-75. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mentges B, Buess G, Effinger G, Manncke K, Becker HD. Indications and results of local treatment of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1997;84:348-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee W, Lee D, Choi S, Chun H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical surgery for T1 and T2 rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1283-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jin Z, Yin L, Xue L, Lin M, Zheng Q. Anorectal functional results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery in benign and early malignant tumors. World J Surg. 2010;34:1128-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ramirez JM, Aguilella V, Arribas D, Martinez M. Transanal full-thickness excision of rectal tumours: should the defect be sutured? a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Herman RM, Richter P, Walega P, Popiela T. Anorectal sphincter function and rectal barostat study in patients following transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:370-376. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kennedy ML, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery excision: is anorectal function compromised? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:601-604. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kreis ME, Jehle EC, Haug V, Manncke K, Buess GF, Becker HD, Starlinger MJ. Functional results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1116-1121. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mora López L, Serra Aracil J, Rebasa Cladera P, Puig Divi V, Hermoso Bosch J, Bombardo Junca J, Alcántara Moral M, Hernando Tavira R, Ayguavives Garnica I, Navarro Soto S. [Anorectal disorders in the immediate and late postoperative period after transanal endoscopic microsurgery]. Cir Esp. 2007;82:285-289. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gracia Solanas JA, Ramírez Rodríguez JM, Aguilella Diago V, Elía Guedea M, Martínez Díez M. A prospective study about functional and anatomic consequences of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98:234-240. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wang HS, Lin JK, Yang SH, Jiang JK, Chen WS, Lin TC. Prospective study of the functional results of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1376-1380. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Banerjee AK, Jehle EC, Kreis ME, Schott UG, Claussen CD, Becker HD, Starlinger M, Buess GF. Prospective study of the proctographic and functional consequences of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg. 1996;83:211-213. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Duthie HL, Watts JM. Contribution of the external anal sphincter to the pressure zone in the anal canal. Gut. 1965;6:64-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ihre T. Studies on anal function in continent and incontinent patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1974;25:1-64. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Frenckner B, Euler CV. Influence of pudendal block on the function of the anal sphincters. Gut. 1975;16:482-489. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lund JN, Scholefield JH. Aetiology and treatment of anal fissure. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1335-1344. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yamana T, Oya M, Komatsu J, Takase Y, Mikuni N, Ishikawa H. Preoperative anal sphincter high pressure zone, maximum tolerable volume, and anal mucosal electrosensitivity predict early postoperative defecatory function after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1145-1151. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lestar B, Penninckx F, Kerremans R. The composition of anal basal pressure. An in vivo and in vitro study in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gibbons CP, Trowbridge EA, Bannister JJ, Read NW. Role of anal cushions in maintaining continence. Lancet. 1986;1:886-888. [PubMed] |

| 25. | MacDonald A, Smith A, McNeill AD, Finlay IG. Manual dilatation of the anus. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1381-1382. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Horgan PG, O'Connell PR, Shinkwin CA, Kirwan WO. Effect of anterior resection on anal sphincter function. Br J Surg. 1989;76:783-786. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Ho YH, Tsang C, Tang CL, Nyam D, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Anal sphincter injuries from stapling instruments introduced transanally: randomized, controlled study with endoanal ultrasound and anorectal manometry. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:169-173. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Denny-Brown D, Robertson EG. 'An investigation of the nervous control of defecation' by Denny-Brown and Robertson: a classic paper revisited. 1935. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:376-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Duthie HL, Bennett RC. The relation of sensation in the anal canal to the functional anal sphincter: a possible factor in anal continence. Gut. 1963;4:179-182. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Miller R, Bartolo DC, Cervero F, Mortensen NJ. Anorectal sampling: a comparison of normal and incontinent patients. Br J Surg. 1988;75:44-47. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Lane RH, Parks AG. Function of the anal sphincters following colo-anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1977;64:596-599. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Williams NS, Price R, Johnston D. The long term effect of sphincter preserving operations for rectal carcinoma on function of the anal sphincter in man. Br J Surg. 1980;67:203-208. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Suzuki H, Matsumoto K, Amano S, Fujioka M, Honzumi M. Anorectal pressure and rectal compliance after low anterior resection. Br J Surg. 1980;67:655-657. [PubMed] |

| 34. | O'Riordain MG, Molloy RG, Gillen P, Horgan A, Kirwan WO. Rectoanal inhibitory reflex following low stapled anterior resection of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:874-878. [PubMed] |