Published online Oct 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5799

Revised: May 31, 2012

Accepted: June 8, 2012

Published online: October 28, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for foregut neuroendocrine tumors (NETs).

METHODS: From April 2008 to December 2010, patients with confirmed histological diagnosis of foregut NETs were included. None had regional lymph node enlargement or distant metastases to the liver or lung on preoperative computerized tomography scanning or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). ESD was attempted under general anesthesia. After making several marking dots around the lesion, a mixture solution was injected into the submucosa. The mucosa was incised outside the marking dots. Dissection of the submucosal layer beneath the tumor was performed under direct vision to achieve complete en bloc resection of the specimen. Tumor features, clinicopathological characteristics, complete resection rate, and complications were evaluated. Foregut NETs were graded as G1, G2, or G3 on the basis of proliferative activity by mitotic count or Ki-67 index. All patients underwent regular follow-up to evaluate for any local recurrence or distant metastasis.

RESULTS: Those treated by ESD included 24 patients with 29 foregut NETs. The locations of the 29 lesions are as follows: esophagus (n = 1), cardia (n = 1), stomach (n = 23), and duodenal bulb (n = 4). All lesions were found incidentally during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for other indications, and none had symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. Preoperative EUS showed that all tumors were confined to the submucosa. Among the 24 gastric lesions, 16 lesions in 11 patients were type I gastric NETs arising in chronic atrophic gastritis with hypergastrinemia, while the other 8 solitary lesions were type III because of absence of atrophic gastritis in these cases. All of the tumors were removed in an en bloc fashion. The average maximum diameter of the lesions was 9.4 mm (range: 2-30 mm), and the procedure time was 20.3 min (range: 10-45 min). According to the World Health Organization 2010 classification, histological evaluation determined that 26 lesions were NET-G1, 2 gastric lesions were NET-G2, and 1 esophageal lesion was neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC). Complete resection was achieved in 28 lesions (28/29, 96.6%), and all of them were confined to the submucosa in histopathologic assessment with no lymphovascular invasion. The remaining patient with NEC underwent additional surgery because the resected specimens revealed angiolymphatic and muscularis invasion, as well as incomplete resection. Delayed bleeding occurred in 1 case 3 d after ESD, which was managed by endoscopic treatment. There were no procedure-related perforations. During a mean follow-up period of 24.4 mo (range: 12-48 mo), local recurrence occurred in only 1 patient 7 mo after initial ESD. This patient successfully underwent repeat ESD. Metastasis to lymph nodes or distal organs was not observed in any patient. No patients died during the study period.

CONCLUSION: ESD appears to be a safe, feasible, and effective procedure for providing accurate histopathological evaluations and curative treatment for eligible foregut NETs.

- Citation: Li QL, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Ma LL, Qin WZ, Hu JW, Cai MY, Yao LQ, Zhou PH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for foregut neuroendocrine tumors: An initial study. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(40): 5799-5806

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i40/5799.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5799

Depending on the point of origin in the disseminated endocrine system, gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) can be classified as a tumor of the foregut (esophagus, stomach and duodenum), midgut (distal ileum and proximal colon), or hindgut (distal colon and rectum). Foregut NETs are considered rare, and the reported incidence is 10%-30% of all gastrointestinal NETs, but their incidence has been increasing in most countries over the last 50 years[1]. These increases in diagnosed incidence and prevalence are likely attributable, in part, to better awareness and improved diagnostic strategies regarding NETs, as well as the increasingly widespread use of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy[2].

Foregut NETs can show a broad range of clinical behavior, ranging from benign and asymptomatic to disseminated and metastatic. This clinical behavior is a reflection of tumor location, type, grade and stage. With the advent of screening gastroscopy, we currently can diagnose and treat small foregut NETs at a very early stage. Foregut NETs that are limited to the mucosa/submucosa and are less than 11-20 mm in size demonstrate a low frequency of lymph node and distant metastasis, and thus have been managed with local excision (including endoscopic treatment), which offers improved quality of life compared with surgery[3,4]. Nowadays traditional polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) are most commonly employed for some foregut NETs[5-12]. However, complete histological resection may not always be easy to achieve by using EMR because most gastrointestinal NETs are not confined to the mucosa but, rather, invade the submucosa[13], which results in frequent involvement of the resection margin.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a method of endoscopic resection that involves circumferential cutting of the mucosa surrounding the tumor followed by dissection of the submucosa under the lesion. ESD has the advantage of a high probability of en bloc and histologically complete resection even in huge lesions because the technique involves dissection of the submucosal tissue beneath the lesion[14-16]. To date, the fact that ESD can facilitate a histologically complete resection of NETs has been verified for the use of ESD for treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors (now referred to as NETs)[17-19]. However, no systematic data have yet been published in which ESD has been applied to foregut NETs. Thus, we retrospectively evaluated the feasibility and efficacy of ESD for foregut NETs in this study.

With the approval of the institutional review board, 24 patients with confirmed histological diagnosis of foregut neuroendocrine neoplasms were treated with ESD from April 2008 to December 2010. None had regional lymph node enlargement or distant metastases to the liver or lung on computerized tomography (CT) scanning or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) before ESD. Tumor characteristics, complete resection rate, complications, local recurrences, and distant metastases were evaluated in all patients. Informed patient consent was obtained prior to the procedures. The procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (1964, and amended in 1975, 1983, 1989, 1996 and 2000) of the World Medical Association.

Preoperative EUS (high-frequency miniprobe, UM-2R, 12 MHz; UM-3R, 20 MHz, Olympus) was performed to evaluate the depth of tumor invasion and the involvement of regional lymph nodes. The existence of lymph node and distant metastasis was surveyed by contrast-enhanced CT, abdominal ultrasound, and chest X-ray.

To dissect the tumor, ESD was attempted with a single-channel gastroscope (GIF-H260, Olympus) and an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife (KD-611L, Olympus) or hook knife (KD-620LR, Olympus). A transparent cap (D-201-11304, Olympus) was attached to the tip of the gastroscope to provide direct views of the submucosal layer. Other equipment included an injection needle (NM-4L-1, Olympus), grasping forceps (FG-8U-1, Olympus), snare (SD-230U-20, Olympus), hot biopsy forceps (FD-410LR, Olympus), clips (HX-610-90, HX-600-135, Olympus), high-frequency generator (ICC-200, ERBE), and argon plasma coagulation unit (APC300, ERBE).

Patients were treated under general anesthesia. After making several marking dots with argon plasma coagulation around the lesion, a mixture solution (including 100 mL normal saline, 1 mL indigo carmine, and 1 mL epinephrine) was injected into the submucosa. The mucosa was incised outside the marking dots. Direct dissection of the submucosal layer beneath the tumor was then performed under direct vision to achieve a complete en bloc resection of the specimen. The tumor was dissected along the capsule, and saline solution was injected repeatedly during the dissection when necessary. The resultant artificial ulcer was managed routinely with argon plasma coagulation to prevent delayed bleeding and hemoclips were used to close the deeply dissected areas as needed.

The World Health Organization (WHO) 2010 classification of tumors of the digestive system was used for histopathologic evaluation[20] (Table 1). Immunohistochemistry with the two robust neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin was used to reach an accurate diagnosis. The mitotic count per 10 high-power fields or the Ki-67 index per 400 cells-2000 cells was used for grading and staging. On the basis of proliferative activity, foregut neuroendocrine neoplasms were graded as G1, G2 or G3. Low to intermediate grade tumors (G1-G2) were defined as NETs (previously referred to as carcinoids) whereas high-grade carcinomas (G3) were termed neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs).

| Classification | Grading | ||

| Grade | Mitotic count (per 10 HPF) | Ki-67 index (%) | |

| NET | G1 | < 2 | < 2 |

| NET | G2 | 2–20 | 3-20 |

| NEC | G3 | > 20 | > 20 |

en bloc resection refers to a resection in one piece. A resection with a tumor-free margin in which both the lateral and basal margins were free of tumor cells was considered as a complete resection. A resection was considered as an incomplete resection in which the tumor extended into the lateral or basal margin, or the margins were indeterminate because of artificial burn effects.

There is a clinicopathological categorization of gastric NETs which distinguishes the four types of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the stomach[3]: type I are those arising in chronic atrophic gastritis with hypergastrinemia; type II occurs in patients with hypergastrinemia due to Zollinger-Ellison syndrome in association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I; type III are gastric NETs not associated with any specific pathogenetic background; and poorly differentiated NECs are nowadays classified as type IV neuroendocrine neoplasms of the stomach.

Additional surgical intervention was recommended in the case of type I or type II gastric NETs with positive margins, size > 20 mm, G2-G3 histological grading, invasion into the muscularis propria, or vessel infiltration of tumor cells. Additional surgery was also recommended in the case of type III gastric NETs with a size > 10 mm irrespective of other risk factors. Surgery was the only treatment of choice in case of a localized type IV gastric NET.

Surgical indication for esophageal and duodenal NETs is controversial. The indication used in our study corresponded with that of type III gastric NETs.

Patients underwent follow-up endoscopy and/or EUS at 1, 3, 6 and 12 mo after ESD and annually thereafter to view the wound healing and evaluate for any residual tumor or recurrence. Close follow-up was also carried out to evaluate for distant metastasis every 6 mo by abdominal ultrasound, contrast-enhanced CT, and chest radiography.

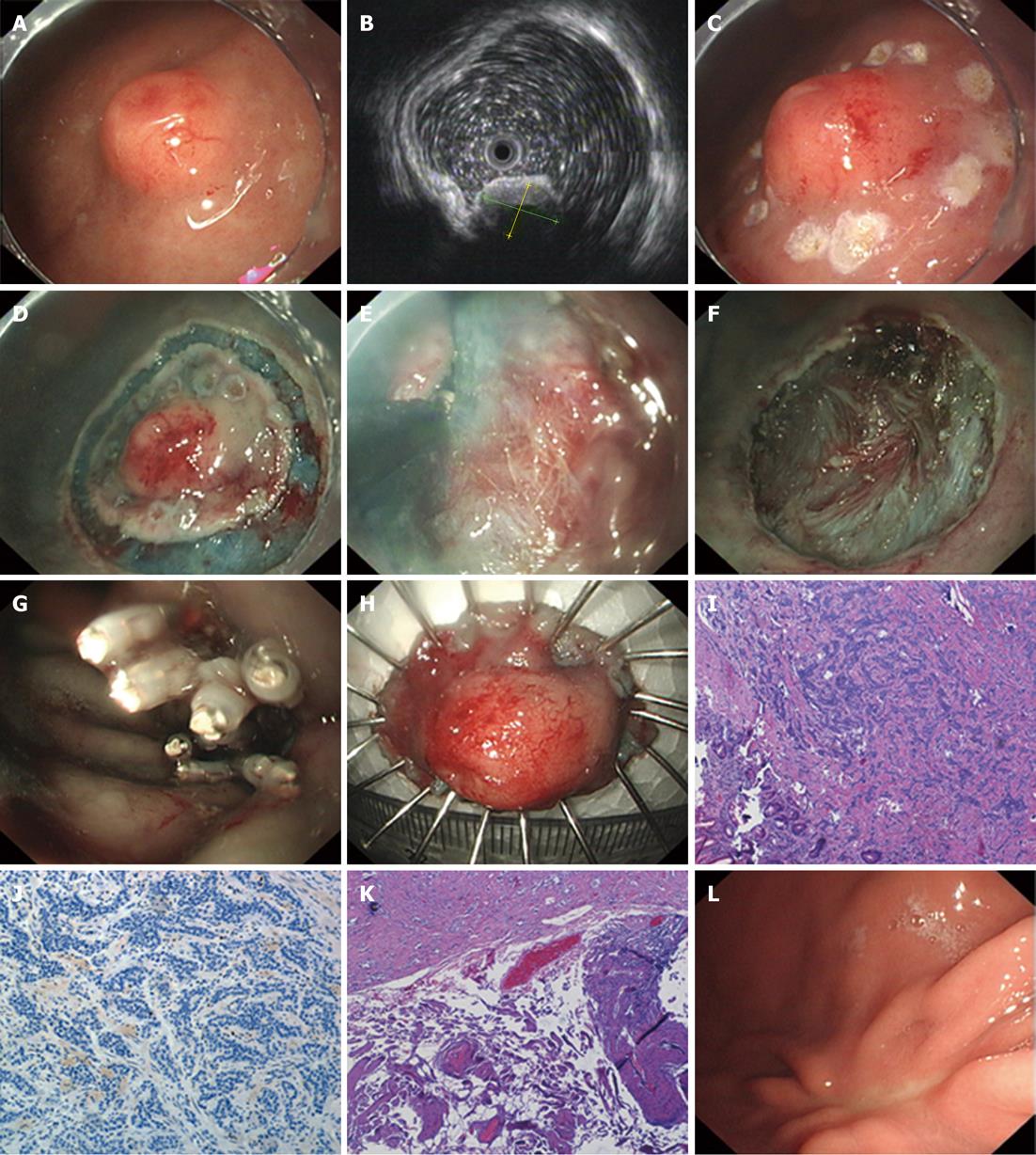

Patient characteristics, lesion features, and clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 2. The study cohort consisted of 9 men (ages 35 to 71 years) and 15 women (ages 35 to 82 years). Of these, 3 cases had 2 tumors and 1 case had 3 tumors (case nos. 12, 14, 20 and 24). The 29 lesions were found in the esophagus (n = 1), gastric cardia (n = 1), stomach (n = 23), or duodenal bulb (n = 4; Figure 1).

| Case no. | Age (yr) | Gender | Location | Macroscopic appearance | Clinicopathological type | Size (mm) | en bloc resection | Depth of invasion | WHO classification | Lateral margin | Vertical margin | Vessel invasion | Complication | Additional surgery | Follow-up (mo) |

| 1 | 41 | M | Gastric antrum | Submucosal tumor | III | 10 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 48 |

| 2 | 53 | M | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | I | 5 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 40 |

| 3 | 71 | M | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | III | 18 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | Reject | 36 |

| 4 | 55 | F | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | III | 10 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 30 |

| 5 | 82 | F | Gastric fundus | Submucosal tumor | III | 30 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G2 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | Reject | 30 |

| 6 | 35 | F | Gastric fundus | Polyp | I | 6 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 30 |

| 7 | 35 | M | Duodenal bulb | Submucosal tumor | NA | 15 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | Reject | 30 |

| 8 | 57 | M | Duodenal bulb | Submucosal tumor | NA | 5 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 30 |

| 9 | 40 | F | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 6 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 30 |

| 10 | 47 | F | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | I | 4 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 30 |

| 11 | 71 | F | Duodenal bulb | Submucosal tumor | NA | 6 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 24 |

| 12 | 56 | F | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 3, 2 | Yes | Mucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 24 |

| 13 | 51 | F | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | III | 8 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 24 |

| 14 | 55 | M | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 8, 3, 3 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 24 |

| 15 | 55 | M | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 4 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 18 |

| 16 | 45 | F | Esophagus | Submucosal tumor | NA | 30 | Yes | Muscularis | NEC | (-) | (+) | Present | None | Yes | 18 |

| 17 | 57 | M | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | III | 15 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | Delayed bleeding | Reject | 22 |

| 18 | 35 | F | Gastric body | Submucosal tumor | III | 25 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G2 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | Yes | 18 |

| 19 | 70 | F | Duodenal bulb | Submucosal tumor | NA | 10 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 18 |

| 20 | 45 | F | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 6, 3 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 12 |

| 21 | 48 | F | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 5 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 12 |

| 22 | 55 | M | Gastric body | Polyp | I | 5 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 12 |

| 23 | 65 | F | Cardia | Submucosal tumor | III | 20 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | Reject | 14 |

| 24 | 35 | F | Gastric fundus | Erosion | I | 5, 3 | Yes | Submucosa | NET-G1 | (-) | (-) | Absent | None | None | 12 |

All lesions were found incidentally during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for other indications such as anemia, reflux symptoms, or nonspecific abdominal symptoms. None had symptoms of carcinoid syndrome. With respect to macroscopic appearance, 15 patients had submucosal tumors with a central depression or erosion on top, 8 patients had sessile polyps with a reddened surface, and 1 patient had an erosion-type tumor.

EUS showed that all tumors were confined to the submucosa. Before ESD procedures, histological diagnosis of foregut NETs had been confirmed via biopsies in 4 cases (case nos. 8, 13, 15 and 22), suspected diagnosis of NETs were made based upon specific macroscopic appearances and EUS characteristics in 15 cases, and an indefinite diagnosis was made in 5 cases (case nos. 5, 7, 16, 18 and 23).

Among the 24 gastric lesions, 16 lesions in 11 patients were type I gastric NETs arising in chronic atrophic gastritis with hypergastrinemia, while the other 8 solitary lesions were type III because of absence of atrophic gastritis. No patient had metastatic disease to lymph nodes or distal organs on preoperative examinations.

All of the tumors were removed in an en bloc fashion (29/29, 100%). The average maximum diameter of the lesions was 9.4 mm (range: 2-30 mm), and the average procedure time was 20.3 min (range: 10-45 min) (Figure 2A-H).

According to the WHO 2010 classification, results of pathological studies determined that 26 lesions were NET-G1, 2 gastric lesions were NET-G2 (case nos. 5 and 18), and 1 esophageal lesion was NEC (case no. 16). In the esophageal lesion defined as NEC, the tumor invaded the muscularis propria and the vertical margin was affected by tumor cells. Lymphatic and vascular invasion were also observed in the resected specimens. This patient thus underwent esophagectomy and excision of regional lymph nodes. Complete resection was achieved for the remaining 28 lesions (28/29, 96.6%), all of which were confined to the submucosa without lymphovascular invasion upon histopathologic assessment (Figures 2I-K).

Delayed bleeding occurred in 1 case 3 d after ESD (case no. 17). Successful hemostasis was achieved by coagulating forceps and spraying with thrombin during emergency endoscopy, and no blood transfusion was necessary. There were no procedure-related perforations.

Additional surgical intervention was considered in 6 cases (case nos. 3, 5, 7, 17, 18 and 23) because duodenal and type III gastric NETs with a diameter larger than 10 mm may have a high risk of metastasis. However, only 1 of the 6 underwent additional surgery (case no. 18), and we could not reveal residual lesions or metastatic lymph nodes in the surgical specimens. The remaining 5 cases refused additional surgery, citing their age, physical condition, or other personal reasons. These patients remained under careful follow-up.

During a mean follow-up period of 24.4 mo (range: 12-48 mo), local recurrence occurred in only 1 patient 7 mo after initial ESD (case no. 14). This patient underwent successful repeat ESD. Metastasis to lymph nodes or distal organs was not observed in any patient, and no patient died during the study period.

Though rare, primary foregut NETs may now be discovered more often with the advent of screening gastroscopy[1]. Nowadays more and more foregut NETs are usually diagnosed at an early stage (tumor size < 11-20 mm and limited to the mucosa/submucosa)[1,3], and thus can be managed with local excision (including endoscopic treatment) because of a low frequency of lymph node and distant metastasis.

As a minimally invasive technique, endoscopic resection may benefit patients diagnosed with foregut NETs. This approach offers the promise of localized treatment of these tumors with relatively few complications and low mortality. Various endoscopic resection procedures have been described as potential treatment procedures for foregut NETs, such as endoscopic polypectomy, strip biopsy, aspiration resection, and band-snare resection[5-12]. However, complete resection of NETs is difficult with conventional polypectomy because most gastrointestinal NETs are not confined to the mucosa but, rather, invade the submucosa[13], which results in frequent involvement of the resection margin. As such, polypectomy may not provide adequate resection margins and additional surgical intervention may be needed.

In the current study we applied ESD to remove foregut NETs. Most of the lesions extended into the submucosa (96.6%, 28/29), and en bloc resection was achieved for all of the tumors in this study. Moreover, a histologically complete resection was achieved for 96.6% (28/29) of the current series. This is important as a high rate of histologically complete resections with ESD may give several advantages for the treatment of foregut NETs[17-19]. First, a histologically complete resection can provide a substantial amount of submucosal tissue, such that an accurate determination of lymphovascular invasion and histological grading is possible, which can inform decisions regarding subsequent therapy. Second, incomplete resection of tumors results in the need for additional surgery, and complete resection for a reduced frequency of unnecessary surgery. Third, repeat endoscopic resection of remnant tumor after an initial incomplete endoscopic resection may be difficult because of fibrosis that prevents lifting the lesion by submucosal injection. Therefore, we recommend histologically complete resection of foregut NETs even when lesions are small, and the present study indicates that ESD may maximize the likelihood of such an outcome because of complete resection.

Bleeding and perforation are the two main complications of ESD. In this study, only 1 case had delayed bleeding 3 d after ESD. Successful hemostasis was achieved by coagulating forceps and spraying with thrombin during emergency endoscopy. No patient had immediate or delayed perforation. The relatively low ESD complication rate most likely reflects the small size of the lesions. Furthermore, we focus heavily on preventing and handling bleeding during the procedure because hemostasis may take a long time to establish and the endoscopic view may be affected. This is important because blind hemostasis may eventually lead to perforation. In our study, immediate minor bleeding was treated successfully by grasping the bleeding vessels with hot biopsy forceps and coagulating them during ESD. Direct coagulation with the hook knife was done for small vessels in the submucosa, and metallic clips were often deployed for more brisk bleeding.

Certain properties of foregut NETs should be considered for rescue surgery after endoscopic resection. The indication for this is usually based on the location, type, grade, and stage of the foregut NET disease. Considering the review of Scherübl et al[3] for the treatment of gastric NETs, in this study additional surgical intervention was recommended in the case of type I or type II gastric NETs with positive margins, size > 20 mm, G2-G3 histological grading, invasion into the muscuralis propria, or vessel infiltration of tumor cells. Additional surgery was also recommended in the case of type III gastric NETs with a size > 10 mm irrespective of other risk factors. Surgery was the only treatment of choice in case of a localized type IV gastric NET. As for the endoscopic treatment of esophageal and duodenal NETs, the indication is controversial. In correspondence to a systemic review[4], additional surgery was recommended in our study in patients with duodenal NETs larger than 10 mm. According to these indications, additional surgical intervention should have been undertaken 7 cases; however, 5 of them refused additional surgery, citing their age, physical condition, or other personal reasons. Nonetheless, during a 2-year follow-up period, local recurrence or distal metastasis didn’t occur in these 5 patients.

Thus, the appropriate selection criteria of foregut NETs for endoscopic resection is still controversial and is in need of further investigation. Because of complete resection, the present study indicates that ESD may reasonably serve as a curative treatment for foregut NETs when lesions are within the existing criteria. ESD also provides enough histological information for tumor grading and staging even when lesions are beyond the selection criteria, which informs decisions regarding subsequent surgery. In addition, endoscopic treatment might also be considered in particular in patients with a high risk of perioperative complications due to old age or advanced comorbidity, for example, or if there are other contraindications to major surgery, even though the lesions are a little beyond the existing criteria. If EUS is able to rule out invasion of the muscularis propria, the upper size limit for the lesion would only be restricted by what is endoscopically practicable[4]. If endoscopy is deemed unsuitable, laparoscopic techniques could be another attractive alternative[21,22].

In conclusion, ESD may be considered for the treatment of eligible foregut NETs because the technique shows a high histologically complete resection rate, provides accurate histopathological evaluation, has a low complication rate, and can be performed within a reasonable timeframe. Issues to be addressed in future prospective studies include identification of appropriate selection criteria and analysis of long-term results after ESD treatment of foregut NETs.

With the advent of screening gastroscopy, foregut neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) can be diagnosed at a very early stage and thus managed with local excision, including endoscopic treatment. However, complete resection of NETs is difficult with conventional polypectomy because most gastrointestinal NETs are not confined to the mucosa but, rather, invade the submucosa, which results in frequent involvement of the resection margin.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a method of endoscopic resection that involves circumferential cutting of the mucosa surrounding the tumor followed by dissection of the submucosa under the lesion. ESD has the advantage of a high probability of en bloc and histologically complete resection even in huge lesions because the technique involves dissection of the submucosal tissue beneath the lesion. To date, the fact that ESD can facilitate histologically complete resection of NETs has been verified on the use of ESD for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors (now referred to as NETs). However, no systematic studies have yet been published in which ESD has been applied for foregut NETs.

In the current study, the authors reported for the first time that ESD can reasonably serve as curative treatment for eligible foregut NETs when lesions are within the existing criteria. ESD also provides enough histological information for tumor grading and staging even when the lesions are beyond the selection criteria, which informs decisions regarding subsequent surgery.

The study suggests that ESD should be considered for treatment of eligible foregut NETs. Issues to be addressed in future prospective studies include identification of appropriate selection criteria and analysis of long-term results after ESD treatment of foregut NETs.

Gastrointestinal NETs can be classified as tumor of the foregut (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum), midgut (distal ileum and proximal colon), or hindgut (distal colon and rectum).

This is a good descriptive study reporting the results of endoscopic treatment for the resection of foregut NETs. The results are interesting and suggest that ESD may be considered for treatment of eligible foregut NETs because the technique shows a high histologically complete resection rate, provides accurate histopathological evaluation, has a low complication rate, and can be performed within a reasonable timeframe.

Peer reviewers: Masahiro Tajika, MD, PhD, Department of Endoscopy, Aichi Cancer Center Hospital, 1-1 Kanokoden, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464-8681, Japan; Giovanni D De Palma, Professor, Department of Surgery and Advanced Technologies, University of Naples Federico II, School of Medicine, 80131 Naples, Italy; Yuji Naito, Professor, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto 602-8566, Japan

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kulke MH, Scherübl H. Accomplishments in 2008 in the management of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3:S62-S66. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Scherübl H, Cadiot G, Jensen RT, Rösch T, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (gastric carcinoids) are on the rise: small tumors, small problems? Endoscopy. 2010;42:664-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dalenbäck J, Havel G. Local endoscopic removal of duodenal carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2004;36:651-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamamoto C, Aoyagi K, Suekane H, Iida M, Hizawa K, Kuwano Y, Nakamura S, Fujishima M. Carcinoid tumors of the duodenum: report of three cases treated by endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 1997;29:218-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nishimori I, Morita M, Sano S, Kino-Ohsaki J, Kohsaki T, Suenaga K, Yokoyama Y, Onishi S, Sugimoto T, Araki K. Endosonography-guided endoscopic resection of duodenal carcinoid tumor. Endoscopy. 1997;29:214-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshikane H, Goto H, Niwa Y, Matsui M, Ohashi S, Suzuki T, Hamajima E, Hayakawa T. Endoscopic resection of small duodenal carcinoid tumors with strip biopsy technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:466-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zyromski NJ, Kendrick ML, Nagorney DM, Grant CS, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Thompson GB, Farley DR, Sarr MG. Duodenal carcinoid tumors: how aggressive should we be? J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:588-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ichikawa J, Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Kida Y, Imaizumi H, Kida M, Saigenji K, Mitomi H. Endoscopic mucosal resection in the management of gastric carcinoid tumors. Endoscopy. 2003;35:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hopper AD, Bourke MJ, Hourigan LF, Tran K, Moss A, Swan MP. En-bloc resection of multiple type 1 gastric carcinoid tumors by endoscopic multi-band mucosectomy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1516-1521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yokoyama S, Takifuji K, Tani M, Kawai M, Naka T, Uchiyama K, Yamaue H. Endoscopic resection of duodenal bulb neuroendocrine tumor larger than 10 mm in diameter. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Merola E, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Panzuto F, D'Ambra G, Di Giulio E, Pilozzi E, Capurso G, Lahner E, Bordi C, Annibale B. Type I gastric carcinoids: a prospective study on endoscopic management and recurrence rate. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:207-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yoshikane H, Tsukamoto Y, Niwa Y, Goto H, Hase S, Mizutani K, Nakamura T. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: evaluation with endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:375-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gotoda T, Kondo H, Ono H, Saito Y, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Yokota T. A new endoscopic mucosal resection procedure using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for rectal flat lesions: report of two cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:560-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ono S, Kobayashi K, Hashimoto T, Yamamichi N, Tateishi A. Successful outcomes of a novel endoscopic treatment for GI tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with a mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, glycerin, and sugar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rösch T, Sarbia M, Schumacher B, Deinert K, Frimberger E, Toermer T, Stolte M, Neuhaus H. Attempted endoscopic en bloc resection of mucosal and submucosal tumors using insulated-tip knives: a pilot series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:788-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou PH, Yao LQ, Qin XY, Xu MD, Zhong YS, Chen WF, Ma LL, Zhang YQ, Qin WZ, Cai MY. Advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection with needle-knife over endoscopic mucosal resection for small rectal carcinoid tumors: a retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2607-2612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee DS, Jeon SW, Park SY, Jung MK, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK. The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal carcinoid tumors: comparison with endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2010;42:647-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park HW, Byeon JS, Park YS, Yang DH, Yoon SM, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise N, editors . WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC Press 2010; . |

| 21. | Ozao-Choy J, Buch K, Strauchen JA, Warner RR, Divino CM. Laparoscopic antrectomy for the treatment of type I gastric carcinoid tumors. J Surg Res. 2010;162:22-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsujimoto H, Ichikura T, Nagao S, Sato T, Ono S, Aiko S, Hiraki S, Yaguchi Y, Sakamoto N, Tanimizu T. Minimally invasive surgery for resection of duodenal carcinoid tumors: endoscopic full-thickness resection under laparoscopic observation. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |