Published online Oct 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5616

Revised: August 22, 2012

Accepted: August 26, 2012

Published online: October 21, 2012

AIM: To compare postoperative complications and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with different routes of reconstruction.

METHODS: After obtaining approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, we retrospectively reviewed data from 306 consecutive patients with histologically diagnosed esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who were treated between 2001 and 2011. All patients underwent radical McKeown-type esophagectomy with at least two-field lymphadenectomy. Regular follow-up was performed in our outpatient department. Postoperative complications and long-term survival were analyzed by treatment modality, baseline patient characteristics, and operative procedure. Data from patients treated via the retrosternal and posterior mediastinal routes were compared.

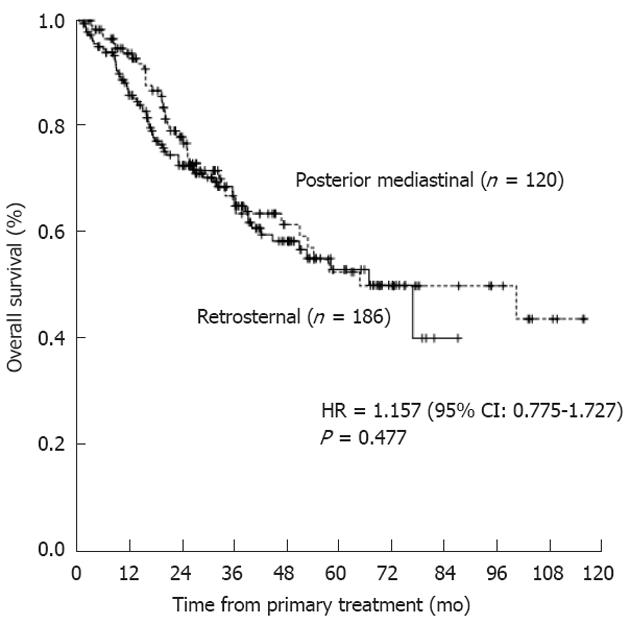

RESULTS: The posterior mediastinal and retrosternal reconstruction routes were employed in 120 and 186 patients, respectively. Pulmonary complications were the most common complications experienced during the postoperative period (46.1% of all patients; 141/306). Compared to the retrosternal route, the posterior mediastinal reconstruction route was associated with a lower incidence of anastomotic stricture (15.8% vs 27.4%, P = 0.018) and less surgical bleeding (242.8 ± 114.2 mL vs 308.2 ± 168.4 mL, P < 0.001). The median survival time was 26.8 mo (range: 1.6-116.1 mo). Upon uni/multivariate analysis, a lower preoperative albumin level (P = 0.009) and a more advanced pathological stage (pT; P = 0.006; pN; P < 0.001) were identified as independent factors predicting poor prognosis. The reconstruction route did not influence prognosis (P = 0.477).

CONCLUSION: The posterior mediastinal route of reconstruction reduces incidence of postoperative complications but does not affect survival. This route is recommended for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

- Citation: Zheng YZ, Dai SQ, Li W, Cao X, Wang X, Fu JH, Lin P, Zhang LJ, Lu B, Wang JY. Comparison between different reconstruction routes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(39): 5616-5621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i39/5616.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i39.5616

The therapeutic treatment of esophageal cancer has undergone important changes over the past several decades. For patients with localized esophageal cancer, subtotal esophagectomy with a thoracic-abdominal-cervical incision (McKeown-type esophagectomy), combined with extensive lymphadenectomy, is now generally recognized as the optimal treatment in terms of long-term survival[1-5].

After subtotal esophagectomy, a gastric tube formed by resection of the lesser curvature is generally considered to be the most suitable esophageal substitute available[6-10]. Reconstruction under such circumstances commonly uses either the posterior mediastinal (PM) or retrosternal (RS) route[6,10,11]. However, the optimal route remains controversial, principally because most previous studies focused exclusively on postoperative complications and quality of life, rather than prognosis[6-9,12].

Thus, for the first time, we conducted a retrospective study to compare not only the incidence of postoperative complications but also prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) treated via the PM and RS routes.

After approval was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, 306 patients diagnosed with ESCC were consecutively recruited between January 2001 and March 2011. Careful preoperative evaluations were conducted to ensure that there were no contraindications to surgical treatment. All patients included in the present evaluation underwent radical esophagectomy. Exclusion criteria included any history of malignant disease, the presence of a second primary tumor, prior non-curative resection (R1/R2), prior use of an esophageal substitute that was not a gastric tube, and any prior neoadjuvant treatment. Disease was staged based on the recommendations of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC 2010). The baseline characteristics of the 306 patients enrolled in the present study are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Data | Route of reconstruction (%) | |

| Posterior mediastinal | Retrosternal | ||

| Age (yr) | |||

| Median | 58.3 | 58.6 | 58.2 |

| Range | 32-79 | 32-79 | 34-78 |

| ≤ 651 | 233 | 90 (75.0) | 143 (76.9) |

| > 65 | 73 | 30 (25.0) | 43 (23.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 237 | 95 (79.2) | 142 (76.3) |

| Female | 69 | 25 (20.8) | 44 (23.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Median | 22.3 | 22.2 | 22.3 |

| Range | 15.2-35.9 | 15.2-33.8 | 15.2-35.9 |

| Smoking index | |||

| Median | 444.2 | 483.6 | 418.7 |

| Range | 0-3330 | 0-3330 | 0-2000 |

| ≤ 4002 | 174 | 67 (55.8) | 107 (57.5) |

| > 400 | 132 | 53 (44.2) | 79 (42.5) |

| Tumor location | |||

| Upper thorax | 46 | 8 (6.7) | 38 (20.4) |

| Middle thorax | 153 | 54 (45.0) | 99 (53.2) |

| Lower thorax | 107 | 58 (48.3) | 49 (26.3) |

| pT status (UICC 7th) | |||

| pT1 | 30 | 11 (9.2) | 19 (10.2) |

| pT2 | 55 | 26 (21.7) | 29 (15.6) |

| pT3 | 221 | 83 (69.2) | 138 (74.2) |

| pN status (UICC 7th) | |||

| pN0 | 139 | 58 (48.3) | 81 (43.5) |

| pN1 | 93 | 36 (30.0) | 57 (30.6) |

| pN2 | 53 | 16 (13.3) | 37 (19.9) |

| pN3 | 21 | 10 (8.3) | 11 (5.9) |

| Tumor grade (UICC 7th) | |||

| G1 | 90 | 41 (34.2) | 49 (26.3) |

| G2 | 168 | 59 (49.2) | 109 (58.6) |

| G3 | 48 | 20 (16.7) | 28 (15.1) |

All patients underwent McKeown-type esophagectomy with at least two-field lymphadenectomy, as described in previous studies[1,4,5]. Three-field lymphadenectomy was performed only if the cervical lymph nodes were thought to be abnormal upon preoperative evaluation. No definitive criteria have been established, therefore, each reconstructive option was determined by the individual surgeon. Pyloroplasty was performed if a patient showed abnormal gastric motility preoperatively. Neither a manubrium nor a partial clavicle was reconstructed.

Complications that occurred during hospital stay and during long-term follow-up were recorded. These included anastomotic leakage, chylothorax, pulmonary complications, cardiac complications, and recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) palsy. Drainage, conservative management, symptomatic and function-supportive treatment, and observation, respectively, were used as initial treatments. The treatment of choice for anastomotic stricture (the options included bougienage and stent placement) depended on the extent and history of the stricture. Surgical details, and complications, are summarized in Table 2.

| Variable | Route of reconstruction (%) | P value | |

| PM | RS | ||

| No. of patients | 120 | 186 | |

| Lymphadenectomy | |||

| Three-field | 29 (24.2) | 32 (17.2) | |

| Two-field | 91 (75.8) | 154 (82.8) | 0.137 |

| Pyloroplasty | 5 (4.2) | 9 (4.8) | 0.784 |

| Anastomosis | |||

| Left neck | 110 (91.7) | 176 (94.6) | |

| Right neck | 8 (6.7) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Intrathoracic | 2 (1.7) | 4 (2.2) | 0.360 |

| Thoracic duct | |||

| Reserved | 27 (22.5) | 80 (43.0) | |

| Ligation | 80 (66.7) | 104 (55.9) | |

| Resected | 13 (10.8) | 2 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Surgical bleeding (mL) | 242.8 ± 114.2 | 308.2 ± 168.4 | < 0.001 |

| Complications (short-term) | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 15 (12.5) | 23 (12.4) | |

| Cervical | 13 (10.8) | 19 (10.2) | |

| Intrathoracic | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Mediastinal | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Esophagotracheal | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.573 |

| Chylothorax | 2 (1.7) | 17 (9.1) | 0.008 |

| Pulmonary | 50 (41.7) | 91 (48.9) | 0.214 |

| Cardiac | 16 (13.3) | 20 (10.8) | 0.494 |

| RLN palsy | 22 (18.3) | 31 (16.7) | 0.707 |

| Complications (long-term) | |||

| Anastomotic stricture | 19 (15.8) | 51 (27.4) | 0.018 |

After completion of primary treatment, patients were followed up in our outpatient department every 4-6 mo for the first 3 years and every 12 mo thereafter. Radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy and/or surgical resection were adopted if and when local recurrence and/or metastasis occurred. The chosen treatment modality was determined by consideration of symptoms, the physical condition of the patient, and the clinical stage of disease. Patient-specific therapeutic schedules used the best available remedies at any time. Survival status was explored via direct telecommunication with patients or family members in October 2011.

We used SPSS 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) for statistical analysis. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the date of death or final clinical follow-up. Correlations between the reconstructive route and clinicopathological characteristics and postoperative complications were assessed using the t and χ2 tests. To detect factors associated with an increased risk of chylothorax, crude and adjusted analyses were performed using both univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Survival was analyzed via the Kaplan-Meier method and the differences between curves were assessed with the aid of the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox’s regression analysis was performed with inclusion of parameters that prior univariate analysis had identified as significant. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Of the 306 patients, 120 and 186 were treated via PM and RS reconstruction, respectively. Baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Pulmonary complications were the most common during the perioperative period (46.1% of all patients; 141/306). Patients in the RS group were more likely to preserve the thoracic duct (P < 0.001). The mean blood loss was 282.6 mL for the entire cohort and was 65.4 mL greater in the RS group than in the PM group (P < 0.001). A positive association between development of chylothorax and use of the RS route was observed (P = 0.008). Anastomotic stricture, the combined incidence of which was 12.4% (38/306), was more common in the RS than in the PM group (P = 0.018). Details of the operations and complications are listed in Table 2. Upon subgroup analysis, RLN palsy was found to be highly associated with three-field lymphadenectomy (P = 0.094) and anastomotic fistula (P = 0.043) (Table 3).

| Variable | Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (%) | P value |

| Lymphadenectomy | ||

| Three-field | 15 (24.6) | |

| Two-field | 38 (12.4) | 0.094 |

| Anastomotic fistula | ||

| No | 42 (15.6) | |

| Yes | 11 (28.9) | 0.043 |

The median follow-up interval was 32.1 mo for surviving patients. A total of 201 patients were alive at last follow-up. The predicted 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates after primary surgery were 75%, 60% and 50% respectively. The median survival time was 26.8 mo (range: 1.6-116.1 mo).

Preoperative albumin level (P = 0.009), pT status (P = 0.006), and pN status (P < 0.001) were independent factors prognostic for survival upon uni/multivariate analysis (Table 4). However, reconstruction route was not a significant prognostic factor (P = 0.477; Figure 1).

| Factor | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value1 | HR (95% CI) | P value1 | |

| Age (yr)2 | 1.642 (1.097-2.460) | 0.016 | 1.013 (0.991-1.035) | 0.245 |

| Sex3 | 0.690 (0.431-1.107) | 0.124 | 0.690 (0.428-1.112) | 0.127 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.974 (0.917-1.035) | 0.400 | ||

| Smoking index4 | 1.499 (1.019-2.204) | 0.040 | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.596 |

| Preoperative albumin level (g/L) | 0.952 (0.917-0.988) | 0.009 | 0.949 (0.912-0.987) | 0.009 |

| Tumor location5 | 0.872 (0.663-1.148) | 0.330 | ||

| pT6 | 1.768 (1.209-2.585) | 0.003 | 1.708 (1.163-2.508) | 0.006 |

| pN7 | 1.903 (1.571-2.306) | < 0.001 | 1.848 (1.525-2.239) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor grade8 | 0.984 (0.731-1.324) | 0.915 | ||

| Surgical bleeding | 1.001 (0.999-1.002) | 0.285 | ||

| Lymphadenectomy | 0.655 (0.384-1.115) | 0.119 | 0.779 (0.454-1.339) | 0.367 |

| Reconstruction9 | 1.157 (0.775-1.727) | 0.477 | ||

In the present study of patients with histologically diagnosed esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who underwent radical McKeown-type esophagectomy with at least two-field lymphadenectomy, we compared survival and complications in patients according to whether the RS or PM route was used. Our work had the advantages that it was performed in patients with the same disease etiology treated with a uniform therapeutic modality, and who underwent long-term follow-up focusing not only on postoperative complications but also on prognosis.

We confirmed that the reconstruction route was not associated with any significant variance in the extent of cardiac (P = 0.494) or pulmonary (P = 0.214) complications, as has been shown in previous studies[6,7,10].

The incidence of RLN palsy was 17.3% in our entire cohort, and did not differ between the PM and RS groups (P = 0.707). In esophagectomy patients, the prime etiology of RLN palsy is direct mechanical injury inflicted on the RLN during dissection[5,13]. Fang et al[14] reported that development of RLN palsy was closely linked to cervical dissection (22.9% vs 9.6%, P = 0.089) and anastomotic leakage (53.8% vs 13.5%, P = 0.001). These data lend support to our conclusion that surgical trauma and fistula-induced secondary corrosion play important roles in the development of RLN palsy (Table 3). Thus, RLN injury would be reduced if trauma during cervical lymphadenectomy were minimized and new anastomotic fistulae were managed in a timely manner.

The conduit is longer when the posterior route of reconstruction is used, therefore, a higher frequency of anastomotic leakage would be expected because a segment of stomach that is more remote from the blood supply is used (compared to the RS route)[8,9]. However, a recent meta-analysis by Urschel et al[10] showed that the reconstruction route chosen did not affect the frequency of anastomotic fistula (95% CI: 0.35-2.94; P = 0.98), in agreement with our data. Additionally, we found a significant association between anastomotic stricture and use of the RS route (P = 0.018). After review of the literature, we suggest that patients undergoing RS reconstruction are more at risk of anatomic stricture because of the narrow entrance to the thoracic inlet and the severe foregut angulation that are created when the RS route is used[7,11,15]. In this context, some authors recommend removal of the manubrium and the sternoclavicular joints[16,17]. We did not take these options; rather we prioritized thoracic stability and better patient appearance. Also, application of cervical anastomosis, which permits better intraoperative exposure at the cost of more severe postoperative pressure, has been reported to decrease fistula but increases stricture development[18]. This was not observed in our present work (anastomotic fistula, P = 0.182; anastomotic stricture, P = 0.110) (data not shown).

Chylothorax, the overall incidence of which was 6.2%, was significantly associated with use of the RS route (P = 0.008). However, prophylactic thoracic duct ligation or resection, which is known to mitigate against chylothorax[19,20], was more likely to be performed in patients of the PM group (P < 0.001). Additionally, each reconstructive option was determined by the preference of the individual surgeon. Therefore, surgeon characteristics and decisions regarding whether to perform thoracic duct ligation or resection seemed to be the major factors contributing to the higher incidence of chylothorax observed in the RS group. The route of reconstruction may not be important, in agreement with the data of previous studies[11,12].

Turning to surgical bleeding, Turnbull et al[21] considered that such bleeding was reduced when the PM technique was used because the extent of tunneling associated with this approach is less than that required when RS reconstruction is used. This is in line with the findings of the present study (P < 0.001). Although bleeding often requires blood transfusion, the clinical significance of a 64.5-mL loss of blood is marginal.

In the present study, the 5-year OS rate was 50% (median: 26.8 mo), which was better than in previous studies[1,3]. This can be attributed to the strict enrolment criteria. Specifically, to facilitate objective comparisons, we excluded patients with pT4-stage disease, those with preoperative metastasis, and those who underwent non-radical (R1/R2) resections.

To date, the most commonly cited argument as to why the RS route of reconstruction should be favored is that it affords a radiotherapeutic advantage if local recurrence occurs[6,7], thus contributing to a favorable prognosis. However, to the best of our knowledge, no prior study has evaluated long-term survival in patients treated via the RS and PM reconstructive routes. Only the biological behavior of a tumor and the chosen treatment modality could influence survival. Thus, the objective of the present study was not to verify the independently prognostic significance of a given reconstructive route but to ascertain whether the route of reconstruction influenced the efficacy of a uniform treatment modality, thereby inducing a difference in survival. To explore this question, we performed prognostic analysis but failed to demonstrate any significant survival difference according to whether the RS or PM route was used (median OS, 25.4 mo vs 27.4 mo; P = 0.477) (Figure 1). Several possible explanations may be advanced. First, improvements in patient selection and surgical techniques, especially in the context of McKeown-type esophagectomy combined with extended lymphadenectomy, have decreased the rates of local recurrence[4,7,22]. Second, various treatment modalities (chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and/or surgical resection) have been shown to be satisfactory in terms of efficacy and to allow acceptable levels of post-recurrence survival[23-26]. Thus, recurrence is no longer an intractable problem for which no effective treatment is available.

Several prognostic factors were identified upon uni/multivariate survival analysis; these included preoperative albumin level and pathological stage (pT and pN status). Lower preoperative albumin levels have long been regarded as indicative of poor nutritional status, abnormal liver function, and a metabolic response to acute phase disease[27,28]. A lower albumin level was significantly associated with a shorter survival time (P = 0.009). A similar result was reported by Lien et al[29] in patients with adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. The importance of pathological stage, the best-established prognostic factor for malignant disease, was emphasized once again in our present work.

The present study has both strengths and weaknesses. The work was retrospective in nature. All work was performed in a single institution, with patients who had disease of uniform etiology and who were identically treated. However, the data may be biased to some extent, because we could not control for surgical experience or guarantee that all documentation was completely accurate. However, we attempted to minimize the latter possible source of error by using consistent definitions when performing our review of records, and all data were independently checked.

In conclusion, this is believed to be the first retrospective study to investigate systematically the influence of reconstructive route on both clinical complications and prognosis. Use of the PM route of reconstruction reduces the incidence of postoperative complications, without compromising survival, and must be recommended for use in patients with resectable ESCC.

For patients with localized esophageal cancer, subtotal esophagectomy with a thoracic-abdominal-cervical incision (McKeown-type esophagectomy), combined with extensive lymphadenectomy, is now generally recognized as the optimal treatment in terms of long-term survival. Reconstruction under such circumstances commonly uses either the posterior mediastinal (PM) or retrosternal (RS) route. Despite studied and debated for decades, there remains no consensus as to the optimal route of reconstruction after subtotal esophagectomy.

Postoperative complications and quality of life are hot topics and have been analyzed in previous studies. A recent meta-analysis showed that PM and anterior mediastinal routes of reconstruction are associated with similar outcomes.

To date, the most commonly cited argument as to why the RS route of reconstruction should be favored is that it affords a radiotherapeutic advantage if local recurrence occurs, thus contributing to a favorable prognosis. However, no prior study has evaluated long-term survival and, their results may be biased based on their small sample size. The authors’ work had the advantages that it was performed in a large cohort with the same disease etiology treated with a uniform therapeutic modality, and who underwent long-term follow-up focusing not only on postoperative complications but also on prognosis.

Use of the PM route of reconstruction reduces the incidence of postoperative complications but does not affect survival. This route is recommended for treatment of patients with resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

This paper is well written. The authors retrospectively reviewed 306 consecutive patients. They described that choice of reconstruction method was determined by surgeon preference, because there are still no criteria. Therefore, the surgeon factor should be included in all analyses. Especially in the analysis of risk for postesophagectomy chylothorax, the major factor seemed to be the surgeon and not route of reconstruction.

Peer reviewer: Satoru Motoyama, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Akita University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-1-1 Hondo, Akita 010-8543, Japan

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Lerut T, Nafteux P, Moons J, Coosemans W, Decker G, De Leyn P, Van Raemdonck D, Ectors N. Three-field lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction in 174 R0 resections: impact on staging, disease-free survival, and outcome: a plea for adaptation of TNM classification in upper-half esophageal carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240:962-972; discussion 972-974. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Altorki N, Kent M, Ferrara C, Port J. Three-field lymph node dissection for squamous cell and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 2002;236:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Morita M, Yoshida R, Ikeda K, Egashira A, Oki E, Sadanaga N, Kakeji Y, Yamanaka T, Maehara Y. Advances in esophageal cancer surgery in Japan: an analysis of 1000 consecutive patients treated at a single institute. Surgery. 2008;143:499-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li H, Yang S, Zhang Y, Xiang J, Chen H. Thoracic recurrent laryngeal lymph node metastases predict cervical node metastases and benefit from three-field dissection in selected patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:548-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pennathur A, Luketich JD. Resection for esophageal cancer: strategies for optimal management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:S751-S756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gawad KA, Hosch SB, Bumann D, Lübeck M, Moneke LC, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Busch C, Küchler T, Izbicki JR. How important is the route of reconstruction after esophagectomy: a prospective randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1490-1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bartels H, Thorban S, Siewert JR. Anterior versus posterior reconstruction after transhiatal oesophagectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1141-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen H, Lu JJ, Zhou J, Zhou X, Luo X, Liu Q, Tam J. Anterior versus posterior routes of reconstruction after esophagectomy: a comparative anatomic study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong AC, Law S, Wong J. Influence of the route of reconstruction on morbidity, mortality and local recurrence after esophagectomy for cancer. Dig Surg. 2003;20:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Urschel JD, Urschel DM, Miller JD, Bennett WF, Young JE. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of route of reconstruction after esophagectomy for cancer. Am J Surg. 2001;182:470-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Lanschot JJ, van Blankenstein M, Oei HY, Tilanus HW. Randomized comparison of prevertebral and retrosternal gastric tube reconstruction after resection of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1999;86:102-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang H, Tan L, Feng M, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Comparison of the short-term health-related quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer with different routes of gastric tube reconstruction after minimally invasive esophagectomy. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nishihira T, Hirayama K, Mori S. A prospective randomized trial of extended cervical and superior mediastinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Am J Surg. 1998;175:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fang WT, Chen WH, Chen Y, Jiang Y. Selective three-field lymphadenectomy for thoracic esophageal squamous carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Orringer MB. Transhiatal esophagectomy without thoracotomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1984;200:282-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Harrison DF. Resection of the manubrium. Br J Surg. 1977;64:374-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kunisaki C, Makino H, Otsuka Y, Kojima Y, Takagawa R, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Nomura M, Akiyama H, Shimada H. Appropriate routes of reconstruction following transthoracic esophagectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1997-2002. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bancu S, Zamfir D, Bara T, Butyurka A, Eşianu M, Borz C, Popescu G, Török A, Bancu L, Turcu M. Cervical anastomotic fistula in surgery of the esophagus. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2006;101:31-33. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Geller JL. Arson in review. From profit to pathology. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15:623-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bolger C, Walsh TN, Tanner WA, Keeling P, Hennessy TP. Chylothorax after oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 1991;78:587-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Turnbull AD, Ginsberg RJ. Options in the surgical treatment of esophageal carcinoma. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1994;4:315-329. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ando N, Ozawa S, Kitagawa Y, Shinozawa Y, Kitajima M. Improvement in the results of surgical treatment of advanced squamous esophageal carcinoma during 15 consecutive years. Ann Surg. 2000;232:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Natsugoe S, Okumura H, Matsumoto M, Uchikado Y, Setoyama T, Uenosono Y, Ishigami S, Owaki T, Aikou T. The role of salvage surgery for recurrence of esophageal squamous cell cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:544-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lin CC, Yeh KH, Yang CH, Hsu C, Tsai YC, Hsu WL, Cheng AL, Hsu CH. Multifractionated paclitaxel and cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with metastatic or recurrent esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:703-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jingu K, Nemoto K, Matsushita H, Takahashi C, Ogawa Y, Sugawara T, Nakata E, Takai Y, Yamada S. Results of radiation therapy combined with nedaplatin (cis-diammine-glycoplatinum) and 5-fluorouracil for postoperative locoregional recurrent esophageal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hsu FM, Lin CC, Lee JM, Chang YL, Hsu CH, Tsai YC, Lee YC, Cheng JC. Improved local control by surgery and paclitaxel-based chemoradiation for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results of a retrospective non-randomized study. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Haupt W, Holzheimer RG, Riese J, Klein P, Hohenberger W. Association of low preoperative serum albumin concentrations and the acute phase response. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Danielsen PL, Agren MS, Jorgensen LN. Platelet-rich fibrin versus albumin in surgical wound repair: a randomized trial with paired design. Ann Surg. 2010;251:825-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lien YC, Hsieh CC, Wu YC, Hsu HS, Hsu WH, Wang LS, Huang MH, Huang BS. Preoperative serum albumin level is a prognostic indicator for adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |