Published online Sep 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4898

Revised: April 19, 2012

Accepted: April 22, 2012

Published online: September 21, 2012

AIM: To define the clinical characteristics, and to assess the management of colonoscopic complications at a local clinic.

METHODS: A retrospective review of the medical records was performed for the patients with iatrogenic colon perforations after endoscopy at a local clinic between April 2006 and December 2010. Data obtained from a tertiary hospital in the same region were also analyzed. The underlying conditions, clinical presentations, perforation locations, treatment types (operative or conservative) and outcome data for patients at the local clinic and the tertiary hospital were compared.

RESULTS: A total of 10 826 colonoscopies, and 2625 therapeutic procedures were performed at a local clinic and 32 148 colonoscopies, and 7787 therapeutic procedures were performed at the tertiary hospital. The clinic had no perforations during diagnostic colonoscopy and 8 (0.3%) perforations were determined to be related to therapeutic procedures. The perforation rates in each therapeutic procedure were 0.06% (1/1609) in polypectomy, 0.2% (2/885) in endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), and 3.8% (5/131) in endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Perforation rates for ESD were significantly higher than those for polypectomy or EMR (P < 0.01). All of these patients were treated conservatively. On the other hand, three (0.01%) perforation cases were observed among the 24 361 diagnostic procedures performed, and these cases were treated with surgery in a tertiary hospital. Six perforations occurred with therapeutic endoscopy (perforation rate, 0.08%; 1 per 1298 procedures). Perforation rates for specific procedure types were 0.02% (1 per 5500) for polypectomy, 0.17% (1 per 561) for EMR, 2.3% (1 per 43) for ESD in the tertiary hospital. There were no differences in the perforation rates for each therapeutic procedure between the clinic and the tertiary hospital. The incidence of iatrogenic perforation requiring surgical treatment was quite low in both the clinic and the tertiary hospital. No procedure-related mortalities occurred. Performing closure with endoscopic clipping reduced the C-reactive protein (CRP) titers. The mean maximum CRP titer was 2.9 ± 1.6 mg/dL with clipping and 9.7 ± 6.2 mg/dL without clipping, respectively (P < 0.05). An operation is indicated in the presence of a large perforation, and in the setting of generalized peritonitis or ongoing sepsis. Although we did not experience such case in the clinic, patients with large perforations should be immediately transferred to a tertiary hospital. Good relationships between local clinics and nearby tertiary hospitals should therefore be maintained.

CONCLUSION: It was therefore found to be possible to perform endoscopic treatment at a local clinic when sufficient back up was available at a nearby tertiary hospital.

- Citation: Sagawa T, Kakizaki S, Iizuka H, Onozato Y, Sohara N, Okamura S, Mori M. Analysis of colonoscopic perforations at a local clinic and a tertiary hospital. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(35): 4898-4904

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i35/4898.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4898

Colonoscopy is widely used for the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of colorectal diseases[1,2]. The improvement of the equipment and increased needs for screening colonoscopy has increased the number of colonoscopies rapidly not only at hospitals but also in clinics. It is convenient for patients to have lesions treated when they are identified by either a routine-check up or diagnostic endoscopy. Therefore, therapeutic endoscopy is sometimes needed at a local clinic, including on the day surgery to perform polypectomy. The occurrence of complications in such cases negatively affects the quality life of these patients. Bleeding after polypectomy is the most common complication[3]. However, the development of endoscopic clipping prevents the occurrence of bleeding after polypectomy[4]. Therefore, cases that need surgical treatment for bleeding after therapeutic procedures are quite rare. Although perforation occurs less often, it is more problematic than bleeding and should be given the most attention[5,6]. Perforations sometimes require surgical intervention and will decrease the patients’ quality of life. Several large, retrospective studies have determined perforation incidences of 0.02%-0.8% and 0.15%-3% for diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy, respectively[6-11].

Surgery has been the mainstream treatment for iatrogenic perforation[12-14]. Surgical treatment for iatrogenic perforation should be avoided at local clinics because most such clinics do not have the appropriate equipment for such surgery. As a result, the performance of therapeutic endoscopy has so far not become common at local clinics. However, the use of endoscopic clipping to prevent the leakage of intestinal contents can circumvent the need for surgery[15,16]. Although surgical treatment should be selected when it is needed, the use of endoscopic clipping could potentially extend the therapeutic indications for such treatments at local clinics.

The aim of this study was to determine the incidences, clinical presentations, and management of iatrogenic perforations that occurred after diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy at a local clinic. This study compared the data between a local clinic and a tertiary hospital. Finally, the optimal strategies for performing therapeutic endoscopy and steps for dealing with complications at local clinics are also discussed.

This study retrospectively reviewed the patient database of colonoscopies, and therapeutic procedures at Shirakawa Clinic (Maebashi, Japan) between April 2006 and December 2010. The data from Maebashi Red Cross Hospital (Maebashi, Japan), a tertiary hospital in the same region were also analyzed and compared between January 1996 and December 2010. Endoscopies at Shirakawa Clinic and Maebashi Red Cross Hospital are performed or supervised by staff gastroenterologists or fellows. The Shirakawa Clinic has 19 inpatient beds and appropriate management, such as drip infusion, can be easily carried out. However, the performance of either surgery or intensive care is restricted and patients required such case are therefore referred to the Maebashi Red Cross Hospital which is a tertiary hospital. Patients that required treatment for an iatrogenic colon perforation during the study period were analyzed. The underlying conditions, clinical presentations, perforation locations, treatment types (operative or conservative), and outcome data were analyzed. Possible complications were explained to all patients before the procedures, and all provided their written consent. Outpatients were informed to contact the clinic if they experienced any post-procedural abdominal distension or pain. This study was approved by the institutional ethical committee (No. SC2011/003; date, December 10, 2010).

The device for diagnostic endoscopy was a single-channel endoscope (CF260AI, Olympus Optical Co, Tokyo, Japan). A single-channel endoscope (GIF230 and/or CF260AI, Olympus) with a hood and a high-frequency generator with an automatically controlled system (Erbotom ICC200 or VIO 300D, ERBE, Tuebingen, Germany) were used for the endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) procedure. The patients principally received 24 mg sennoside the night before the examination for bowel preparation, and drank 200 mL polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution (Niflec®, Ajinomoto Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) every 10 min on the examination day, for a total intake of 2000 mL PEG solution. Polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) were performed as usual[17,18]. The ESD procedure was performed as described previously[19-21]. Abdominal X-rays were routinely performed after therapeutic procedures to check the perforation. Patients without complications were permitted to take soft food the day after the therapeutic procedures. Hemoclips (HX-600-135 and HX-600-090L, Olympus) were used for the endoscopic closure of any perforation.

The data were expressed as the mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using the Fisher’s exact probability test, and Mann-Whitney’s U-test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

A total of 10 826 colonoscopies, and 2625 therapeutic procedures were performed at the Shirakawa Clinic between April 2006 and December 2010. Eight (0.07%) perforations were attributed to endoscopy (Table 1). There were no perforation cases for diagnostic procedures. On the other hand, a therapeutic procedure was performed in the 8 perforation cases (perforation rate, 0.3%; 1 per 328 procedures). The perforation rates for specific procedure types were 0.06% (1 per 1609) for polypectomy, 0.2% (1 per 443) for EMR, and 3.8% (1 per 26) for ESD. Perforation rates for ESD were significantly higher than those for polypectomy or EMR (P < 0.01). The cases with iatrogenic perforation are shown in Table 2. The study group included 3 females and 5 males aged from 57 years to 80 years of age (mean age 67.4 ± 6.6 years).

| Total | Diagnostic | Therapeutic | Polypectomy | EMR | ESD | ||

| Shirakawa Clinic between April 2006 and December 2010 | |||||||

| Number | n | 10 826 | 8201 | 2625 | 1609 | 885 | 131 |

| Perforation | n (%) | 8 (0.07) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.3) | 1 (0.06) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (3.8) |

| Maebashi Red Cross Hospital between January 1996 and December 2010 | |||||||

| Number | n | 32 148 | 24 361 | 7787 | 5500 | 2244 | 43 |

| Perforatio | (%) | 9 (0.03) | 3 (0.01) | 6 (0.08) | 1 (0.02) | 4 (0.17) | 1 (2.3) |

| Case | Age | Gender | Procedure | Site of perforation | Disease | Discovery of perforation | Abdominal pain | Peritonitis sign | Extrabowel gasses | Treatment | Max body temperature (°C) | CRP (mg/dL) | Cessation of food intake (d) | Intravenous antibiotics treatment (d) | Total hospital stay (d) |

| 1 | 71 | F | EMR | Ascending | Adenocarcinoma | Just after procedure | + | No | Free air | Conservative (with clipping) | 36.9 | 4.4 | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| 2 | 57 | M | ESD | Ascending | Adenocarcinoma | During | - | No | Free air | Conservative (with clipping) | 36.8 | 0.9 | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| 3 | 69 | F | ESD | Caecum | Adenoma | During | - | No | PP1 | Conservative (with clipping) | 37.5 | 3.8 | 2 | 8 | 13 |

| 4 | 66 | M | ESD | Rectm (Rb) | Adenoma | Just after procedure | - | No | PP | Conservative (without clipping) | 37.9 | 17.9 | 1 | 6 | 12 |

| 5 | 80 | M | ESD | Caecum | Adenoma | Just after procedure | - | No | Free air | Conservative (without clipping) | 37.0 | 4.2 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| 6 | 68 | M | Polypectomy | Transverse | Adenoma | 1 d after procedure | + | Located | Free air | Conservative (without clipping) | 36.9 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| 7 | 64 | M | EMR | Ascending | Adenocarcinoma | 2 d after procedure | + | Located | Free air | Conservative (without clipping) | 36.9 | 5.5 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| 8 | 64 | F | ESD | Ascending | Adenocarcinoma | During | + | Located | Free air | Conservative (with clipping) | 37.2 | 2.4 | 3 | 5 | 11 |

A total of 32 148 colonoscopies, and 7787 therapeutic procedures were performed in Maebashi Red Cross Hospital, and 9 (0.03%) perforations were attributed to endoscopy (Table 1). There were 3 (0.01%) perforation cases among the diagnostic procedures. Six perforations occurred with therapeutic endoscopy (perforation rate, 0.08%; 1 per 1298 procedures). Perforation rates for specific procedure types were 0.02% (1 per 5500) for polypectomy, 0.17% (1 per 561) for EMR, 2.3% (1 per 43) for ESD. The patients included 3 females and 6 males from 59 years to 81 years of age (mean age 69.2 ± 8.5 years). The cases with perforation during diagnostic endoscopy were complicated with diverticulitis, radiation colitis and amyloidosis, respectively. These 3 perforations during diagnostic endoscopy were treated by surgery. There were no significant differences in the perforation rates for each therapeutic procedure between the local clinic and the tertiary hospital.

Three of 8 cases (37.5%) perforations were detected during the endoscopic procedure due to the visualization of a tear in the serosa. Six (75%) patients were diagnosed to have a perforation within 24 h of colonoscopy. Two patients were diagnosed to have a perforation more than 24 h later. These cases were considered to be delayed perforation caused by electrocautery. Four (50%) of 8 patients had been undergone clipping. Six (75%) patients had free intraperitoneal air and 2 patients showed pneumoretroperitoneum by abdominal radiography or computed tomography (CT). There were no symptoms of peritonitis in 5 patients and 3 patients showed localized peritonitis. All patients were managed conservatively because there no progression to peritonitis symptoms, Conservative treatment included the withholding of oral intake, hydration, intravenous antibiotics and serial abdominal examinations.

The mean maximum C-reactive protein (CRP) titer was 6.3 ± 5.6 mg/dL (range 0.9-17.9 mg/dL) and maximum body temperature was 37.1 ± 0.4 °C (range: 36.8-37.9 °C). The mean fasting period for these patients was 2.3 ± 1.3 d (range: 1-4 d) and the mean hospital stay following perforation was 10.4 ± 1.8 d (range: 7-13 d). The points of references used to discontinue fasting were relief of abdominal pain, improvement of leukocytosis. The mean duration of total intravenous antibiotic treatment was 6.0 ± 1.2 d (range 4-8 d). Flomoxef sodium (FMOX) was administered in all cases. When fasting had been completed, oral ciprofloxacin was prescribed.

The mean maximum CRP titer was 2.9 ± 1.6 mg/dL with clipping and 9.7 ± 6.2 mg/dL without clipping, respectively. The mean maximum CRP titer was significantly lower in the patients with clipping (P < 0.05). The duration of fasting with and without clipping were 1.8 ± 1.0 d and 2.8 ± 1.5 d, respectively. The duration of intravenous antibiotics treatment with and without clipping was 5.8 ± 1.7 d and 6.3 ± 0.5 d, respectively. The duration of total the hospital stay with and without clipping were 10.0 ± 2.6 d and 10.8 ± 1.0 d, respectively. There were no significant differences in the total hospital stay, duration of fasting, dose of intravenous antibiotics between those that had or had not undergone clipping because of the small number of patients with perforation. However, the duration of fasting, dose of intravenous antibiotics and total hospital stay tended to be shorter when clipping was successful in comparison to when clipping was not performed.

Perforation discovered during the therapeutic procedure and treated with clipping: The case was 57-year-old male with no major complications. Perforation was observed during an ESD procedure for ascending colon adenocarcinoma (Figure 1A). Carbon dioxide inflation was used during ESD. Endoscopic clipping closed the small tear of the serosa. Abdominal X-ray showed a small amount of extra-bowel gasses. This case was treated conservatively. FMOX was administered for 4 d. The patient fasted for 1 d and food intake was started at day 3. The patient was discharged at day 9.

Perforation discovered more than 24 h after therapeutic procedure and treated without clipping: The case was a 64-year-old male with a past history of myocardial infarction. Abdominal pain was appeared after 2 d an EMR procedure for ascending colon adenoma. Abdominal XP and CT findings revealed free air (Figure 1B). This case was treated conservatively because the symptoms of peritonitis were localized. FMOX was administered for 6 d. The patient fasted for 4 d and food intake was started at day 6. The patient was discharged on day 11.

Perforation discovered just after a therapeutic procedure and treated with suture clippings: The case was a 71-year-old female complicated with hypertension. This case was treated by usual air inflation during the EMR procedure. Abdominal XP and CT findings revealed free air just after the EMR procedure for ascending colon adenoma (Figure 1C). Inflation was changed to CO2 inflation and endoluminal repair with suture clipping was performed. FMOX was administered for 6 d. The patient fasted for 1 d and food intake was started on day 3. The patient was discharged on day 7.

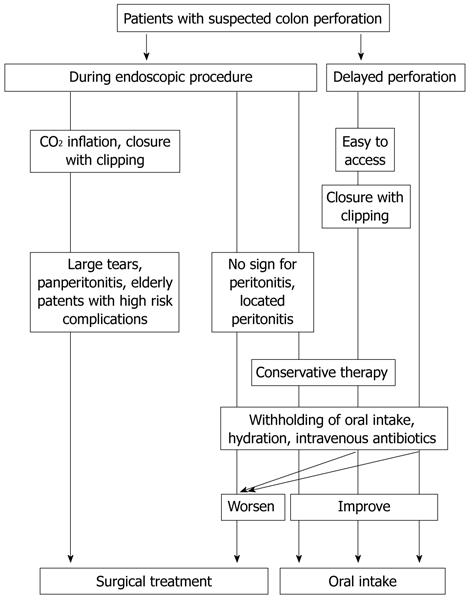

A management algorithm for colonoscopic bowel perforation at a clinic is shown in Figure 2. A minor colon injury that is recognized during colonoscopy should be treated by changing to CO2 inflation, endoluminal repair with clips and further conservative treatment could avoid immediate surgical intervention. Delayed endoscopic repair with clipping should be considered only if the condition of the patient is stable and a specific site is highly suspected. This latter recommendation should be useful when the perforation is suspected in the rectosigmoid area, because perforations in this region are easily located on scope reinsertion. An operation is indicated in the presence of a large perforation, and in the setting of generalized peritonitis or ongoing sepsis. Such patients should be immediately transferred to a tertiary hospital. A good relationship between local clinics and nearby tertiary hospitals should therefore be maintained.

The perforation risks of diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy are 0.02%-0.8% and 0.15%-3%, respectively[6-11]. Large studies of iatrogenic perforation related to colonoscopy are shown in Table 3[6-11,22-24]. New therapeutic approaches including ESD techniques have become more popular and the risk of perforation is increased in comparison to conventional techniques such as polypectomy or EMR. The perforation risk of a therapeutic procedure is usually higher than that of a diagnostic procedure. Fortunately, there were no perforations during diagnostic procedures at the local clinic in the present study.

| Ref. | Total | Diagnostic | Therapeutic | Polypectomy | EMR | ESD |

| Anderson et al[11] | 59 987 | |||||

| 22 (0.04) | ||||||

| Cobb et al[10] | 43 609 | |||||

| 14 (0.03) | ||||||

| Kaneko et al[24] | 3 152 053 | 2 587 689 | 564 364 | 422 119 | 142 245 | ND |

| 1387 (0.04) | 568 (0.02) | 819 (1.4) | 621 (0.15) | 198 (0.14) | ND | |

| Iqbal et al[9] | 78 702 | |||||

| 66 (0.84) | ||||||

| Tulchinsky et al[23] | 120 067 | |||||

| 7 (0.06) | ||||||

| Lüning et al[7] | 30 366 | |||||

| 35 (0.12) | ||||||

| Lüning et al[7] | 433 816 | |||||

| 393 (0.09) | ||||||

| Taku et al[8] | 15 160 | 8240 | 1906 | 43 | ||

| 23 (0.15) | 4 (0.05) | 12 (0.63) | 6 (14.0) | |||

| Kang et al[6] | 44 534 | 37 762 | 6772 | |||

| 53 (0.12) | 26 (0.07) | 27 (0.40) | ||||

| Oka et al[22] | 71 204 | 34 433 | 36 083 | 688 | ||

| 62 (0.09) | 6 (0.02) | 33 (0.09) | 23 (3.3) |

Recent studies have demonstrated the possibility of endoscopic perforation closure using endoclips[25,26]. Closure by endoscopic clipping significantly reduced the maximum CRP titer in this study. Successful closure with endoscopic clipping in conservatively managed patients can reduce the fasting period, duration of intravenous antibiotic administration, and hospital stay[25,26]. As a result, successful clipping can improve patient quality of life and reduce medical costs. This study found no significant differences in the duration of fasting, intravenous antibiotics treatment, total hospital stay between those that had or had not undergone clipping. It may be due to the small number of patients with perforation.

Perforations associated with diagnostic procedures are usually due to applying pressure to the colonic wall, and they are noticed immediately. However, perforations that occur after therapeutic procedures are often diagnosed late. Ischemia of the colonic wall caused by electrical or thermal injury after electrocoagulation can cause a delayed perforation following therapeutic procedures[10]. Clipping can induce mucosal and submucosal healing and prevent fecal soiling of the peritoneal cavity when the perforation is small and significant colonic pathology does not exist. However, the application of clipping for perforation in delayed perforation still remains controversial. Delayed endoscopic repair with clipping should be considered only if the condition of the patient is stable and a specific site is highly suspected[6]. This recommendation is likely to be useful when the perforation is suspected to be in the rectosigmoid area, because perforations in this region are easily located on scope reinsertion[6].

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the work and the inclusion of descriptions of local experience without the addition of new protocols. However, we believe that investigating a large number of patients at a local clinic will elucidate the role the local clinic plays in therapeutic endoscopies. Furthermore, selection bias between the two institutes of patients or endoscopists may have existed. The incidence of complications depends on the type of lesion or the skill of the endoscopist. Selection bias of patients or endoscopists is a problem to be evaluated in a future study.

Selective patients are likely to improve under conservative management involving hospitalization, intestinal rest, intravenous fluids, and antibiotics to limit peritonitis and allow the perforation to seal. However, conservative management requires careful observation with frequent and repeated abdominal exams. Patients successfully treated non-surgically must be clinically stable, and their abdominal symptoms should improve rapidly with no deterioration due to peritoneal signs[14]. A local clinic does not have any surgical options, so a good relationship and close contact with a tertiary hospital is needed. Patients must be immediately transferred to a tertiary hospital when either abdominal symptoms are observed or peritonitis worsens.

In conclusion, iatrogenic colonic perforation is a serious but uncommon complication of colonoscopy. However, surgery is not mandatory for perforations caused by therapeutic procedures, and endoscopic perforation closure using endoclips should be considered as a helpful adjunct to conservative treatment. It is possible to perform endoscopic treatment at a local clinic when there is appropriate back-up by a nearby tertiary hospital. Of course, close contact between local clinics and a tertiary hospital is essential.

The number of colonoscopies has increased rapidly, not only in hospitals, but also in clinics. The occurrence of complications negatively affects the quality life of patients. The aim of this study was to determine the incidence, clinical presentation and management of iatrogenic perforations that occurred after diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopies at a local clinic.

Data and management strategies regarding iatrogenic perforations at hospitals were reported. However, such reports from clinics were rare. Optimal strategies for performing therapeutic endoscopy and steps for managing complications at local clinics were also discussed.

This study investigated the incidence, management and outcomes of colonoscopic perforation in a local clinic. Performing endoscopic perforation closure using endoclips should be considered as a helpful adjunct to conservative treatment. It is possible to perform endoscopic treatment at a local clinic when appropriate back-up support at a nearby tertiary hospital is available.

The number of endoscopic treatments performed at local clinics will increase when appropriate back-up support at nearby tertiary hospitals is available.

A colonoscopic perforation is a complication of diagnostic or therapeutic colonoscopy. Although perforation occurs infrequently, it is problematic and should be given proper attention. Perforations sometimes require surgical intervention, and will decrease a patient’s quality of life.

The study is well designed and the paper is well written. Although there is no novelty in the idea and only a description of the local experience is provided, the study is a nice piece of work that includes a large number of patients.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Daniel R Gaya, Department of Gastroenterology, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Castle Street, Glasgow G4 0SF, United Kingdom; Maha Maher Shehata, Professor, Internal Medicine, Mansoura University, Medical Specialized Hospital, Mansoura 35516, Egypt

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Taupin D, Chambers SL, Corbett M, Shadbolt B. Colonoscopic screening for colorectal cancer improves quality of life measures: a population-based screening study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Forde KA. Colonoscopic screening for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2006;20 Suppl 2:S471-S474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Juillerat P, Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Vader JP, Arditi C, Schusselé Filliettaz S, Dubois RW, Gonvers JJ, Froehlich F, Burnand B, Pittet V. Appropriateness of colonoscopy in Europe (EPAGE II). Presentation of methodology, general results, and analysis of complications. Endoscopy. 2009;41:240-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hachisu T. Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis using an improved clipping apparatus. Surg Endosc. 1988;2:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hagel AF, Boxberger F, Dauth W, Kessler HP, Neurath MF, Raithel M. Colonoscopy-associated perforation: a 7-year survey of in-hospital frequency, treatment and outcome in a German university hospital. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1121-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kang HY, Kang HW, Kim SG, Kim JS, Park KJ, Jung HC, Song IS. Incidence and management of colonoscopic perforations in Korea. Digestion. 2008;78:218-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lüning TH, Keemers-Gels ME, Barendregt WB, Tan AC, Rosman C. Colonoscopic perforations: a review of 30,366 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:994-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Taku K, Sano Y, Fu KI, Saito Y, Matsuda T, Uraoka T, Yoshino T, Yamaguchi Y, Fujita M, Hattori S. Iatrogenic perforation associated with therapeutic colonoscopy: a multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1409-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Iqbal CW, Chun YS, Farley DR. Colonoscopic perforations: a retrospective review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1229-135: discussion 1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cobb WS, Heniford BT, Sigmon LB, Hasan R, Simms C, Kercher KW, Matthews BD. Colonoscopic perforations: incidence, management, and outcomes. Am Surg. 2004;70:750-757. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Anderson ML, Pasha TM, Leighton JA. Endoscopic perforation of the colon: lessons from a 10-year study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3418-3422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Orsoni P, Berdah S, Verrier C, Caamano A, Sastre B, Boutboul R, Grimaud JC, Picaud R. Colonic perforation due to colonoscopy: a retrospective study of 48 cases. Endoscopy. 1997;29:160-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Farley DR, Bannon MP, Zietlow SP, Pemberton JH, Ilstrup DM, Larson DR. Management of colonoscopic perforations. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:729-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lo AY, Beaton HL. Selective management of colonoscopic perforations. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:333-337. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Mana F, De Vogelaere K, Urban D. Iatrogenic perforation of the colon during diagnostic colonoscopy: endoscopic treatment with clips. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:258-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yoshikane H, Hidano H, Sakakibara A, Niwa Y, Goto H. Feasibility study on endoscopic suture with the combination of a distal attachment and a rotatable clip for complications of endoscopic resection in the large intestine. Endoscopy. 2000;32:477-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kedia P, Waye JD. Routine and advanced polypectomy techniques. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:506-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Long WB, Furth EE, Ginsberg GG. Efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection: a study of 101 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:390-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Mori M, Itoh H. Endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Okamura S, Mori M, Itoh H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for rectal tumors. Endoscopy. 2007;39:423-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Onozato Y, Ishihara H, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Kakizaki S, Okamura S, Mori M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers and large flat adenomas. Endoscopy. 2006;38:980-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Oka S, Tanaka S, Kanao H, Ishikawa H, Watanabe T, Igarashi M, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Kobayashi K, Inoue Y. Current status in the occurrence of postoperative bleeding, perforation and residual/local recurrence during colonoscopic treatment in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2010;22:376-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tulchinsky H, Madhala-Givon O, Wasserberg N, Lelcuk S, Niv Y. Incidence and management of colonoscopic perforations: 8 years' experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4211-4213. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kaneko E, Harada H, Kasugai T, Ogoshi K, Niwa H. Fourth national survey report concerning the procedural accidents related to gastrointestinal endoscopy: Five years of data from 1998 to 2002. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2004;46:54-61. |

| 25. | Magdeburg R, Collet P, Post S, Kaehler G. Endoclipping of iatrogenic colonic perforation to avoid surgery. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1500-1504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Taku K, Sano Y, Fu KI, Saito Y. Iatrogenic perforation at therapeutic colonoscopy: should the endoscopist attempt closure using endoclips or transfer immediately to surgery? Endoscopy. 2006;38:428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |