Published online Sep 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4892

Revised: May 2, 2012

Accepted: May 12, 2012

Published online: September 21, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the effect of single nucleotide polymorphisms of interleukin (IL)-28B, rs12979860 on progression and treatment response in chronic hepatitis C.

METHODS: Patients (n = 64; 37 men, 27 women; mean age, 44 ± 12 years) with chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1, received treatment with peg-interferon plus ribavirin. Genotyping of rs12979860 was performed on peripheral blood DNA. Histopathological assessment of necroinflammatory grade and fibrosis stage were scored using the METAVIR system on a liver biopsy sample before treatment. Serum viral load, aminotransferase activity, and insulin level were measured. Insulin resistance index, body mass index, waist/hip ratio, percentage of body fat and fibrosis progression rate were calculated. Applied dose of interferon and ribavirin, platelet and neutrophil count and hemoglobin level were measured.

RESULTS: A sustained virological response (SVR) was significantly associated with IL28B polymorphism (CC vs TT allele: odds ratio (OR), 25; CC vs CT allele: OR, 5.4), inflammation activity (G < 1 vs G > 1: OR, 3.9), fibrosis (F < 1 vs F > 1: OR, 5.9), platelet count (> 200 × 109/L vs < 200 × 109/L: OR, 4.7; OR in patients with genotype CT: 12.8), fatty liver (absence vs presence of steatosis: OR, 4.8), insulin resistance index (< 2.5 vs > 2.5: OR, 3.9), and baseline HCV viral load (< 106 IU/mL vs > 106 IU/mL: OR, 3.0). There was no association with age, sex, aminotransferases activity, body mass index, waist/hip ratio, or percentage body fat. There was borderline significance (P = 0.064) of increased fibrosis in patients with the TT allele, and no differences in the insulin resistance index between groups of patients with CC, CT and TT alleles (P = 0.12). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between insulin resistance and stage of fibrosis and body mass index was r = 0.618 and r = 0.605, respectively (P < 0.001). Significant differences were found in the insulin resistance index (P = 0.01) between patients with and without steatosis. Patients with the CT allele and absence of a SVR had a higher incidence of requiring threshold dose reduction of interferon (P = 0.07).

CONCLUSION: IL28B variation is the strongest host factor not related to insulin resistance that determines outcome of antiviral therapy. Baseline platelet count predicts the outcome of antiviral therapy in CT allele patients.

- Citation: Cieśla A, Bociąga-Jasik M, Sobczyk-Krupiarz I, Głowacki MK, Owczarek D, Cibor D, Sanak M, Mach T. IL28B polymorphism as a predictor of antiviral response in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(35): 4892-4897

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i35/4892.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i35.4892

Investigations on genetic determinants of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) established that a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the interleukin (IL)-28B gene promoter region affected the spontaneous and induced clearance of hepatitis C virus (HCV)[1-5]. Among 500 000 genetic variants which were analyzed genome-wide, a few associated with the virologic response were identified, and showed variable frequency and importance across human ethnic groups[3,5-7]. The mechanism by which SNPs influence the outcome of HCV infection and its treatment is not clear. It is suggested that regulation of the promoter region of IL28B in antiviral activity may also affect two other genes belonging to interferon (IFN)-λ family encoded in this region[6,8-12]. According to some authors, IL28B SNPs are merely indicators of more complex mechanisms of CHC pathogenesis[13]. Some factors which determine the efficacy of antiviral therapy influence the course of CHC[14]. The impact of SNPs within the IL28B region on spontaneous and induced HCV clearance suggests the possibility that polymorphism affects the chronic phase of hepatitis. On the basis of previous research, there is no clear evidence that there is a correlation between IL28B SNPs and progression of untreated CHC. In a meta-analysis by Romero-Gomez et al[15], an effect of IL28B polymorphism on the progression of fibrosis was disputed. Research evaluating liver cirrhosis and fibrosis progression after liver transplantation in HCV-infected patients indicated a connection with IL28B SNPs[16,17].

However, about 50% of patients with a sustained virological response (SVR) do not carry the favorable IL28B alleles[15]. The factors which increase the chance of a therapeutic response in these patients are not yet known. A detailed analysis of the course of therapy of CHC with pegylated IFNα and ribavirin (RBV) in the presence of a hazardous IL28B allele might better delineate the clinical characteristics of this difficult-to-treat group of patients.

The aim of this study was to determine the impact of IL28B polymorphism on the progression of CHC, in order to identify predictors of effective therapy with IFN and RBV in the group of patients with unfavorable IL28B polymorphism.

Sixty-four patients of European origin (Caucasians) with CHC due to HCV genotype 1 were included in the present study. Patients were treated with standard antiviral therapy with pegylated IFN 2a or 2b and RBV according to standard criteria of inclusion and exclusion. A liver biopsy was performed before treatment, and HCV viral load (COBAS® TaqMan® HCV 2.0) and insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR: homeostasis model of assessment) was determined.

The histopathological assessment of necroinflammatory grade and fibrosis stage were scored using the METAVIR system, and the presence of fatty liver disease was taken into consideration. The course of therapy was monitored on the basis of early virologic response (EVR), end of treatment response (ETR) and SVR.

The presence of the IL28B-related SNP rs 12979860 variant was determined in whole blood samples. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples using proteinase K ion exchange column extraction kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland). An amplification product of 190 bp length was obtained using standard polymerase chain reaction with the following primers: 5’- GCC TCT TCC TCC TGC GGG ACA AG and 5’- GCG CGG AGT GCA ATT CAA CCC T. Following digestion with Bsh1236I (BstUI) restriction endonuclease, products were separated using agarose gel electrophoresis. The variant C was digested by the enzyme into fragments. All laboratory procedures were performed on blinded samples.

Patient age, sex, measurable anthropometric parameters such as waist, waist/hip ratio, body mass index (BMI) and percentage of body fat from MALTRON® measurements were analyzed in the present study.

Based on estimated duration of infection, the fibrosis progression rate was defined as the ratio between fibrosis stage and HCV duration. The serum aminotransferase levels prior to the start of treatment and after 72 wk was assessed. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| IL28B polymorphism | n (%) | SVR (%) | Gender (M/F) | Age (yr) | BMI(kg/m2) |

| CC | 13 (20) | 77 | |||

| CT | 34 (53) | 38 | |||

| TT | 17 (27) | 6 | |||

| All | 64 | 39 | 27/37 | 44 ± 12 | 27 ± 5 |

The complete blood count at baseline and its changes during the course of therapy were determined. Thresholds for drug dose reduction were established: white blood cells < 750 cells/µL platelets < 70 000/µL, and hemoglobin < 10 g/L. For each patient the dose of IFN and RBV used in the therapy was established and expressed as a percentage of the recommended dosage. The significance of differences in the clinical parameters as well as anthropometric, biochemical, histological and virological features between patients with and without a SVR was determined based on analysis of variance Kruskal-Wallis rank sum, Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests. A similar analysis was performed on patients only with the IL28B CT genotype. In patients with CC and TT genotypes, analysis of the diversity of the SVR was not performed because of the disproportionate distribution and small number of patients who did or did not achieve a SVR (Table 1).

Using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, we assessed variations in the investigated clinical features between patients with different IL28B polymorphisms. In the logistic regression model we evaluated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of SVR, depending on the degree of inflammatory-necrotic activity, fibrosis scores, platelet count, baseline viral load, insulin resistance index (IR index) and IL28B polymorphisms (Table 2). The OR was determined against cases of high inflammatory-necrotic activity, above grade 1 in the METAVIR score, advanced fibrosis according to METAVIR F > 1, presence of steatosis, viral load > 1 × 106 IU/mL, alleles TT and CT, baseline platelet count < 200 × 109/L and IR index > 2.5.

| Features affecting SVR | P value | OR | 95% CI |

| CC vs TT | < 0.001 | 25 | 3.5-177.5 |

| Platelets CT | 0.002 | 12.8 | 1.8-42.6 |

| Staging | 0.008 | 5.9 | 1.5-23.8 |

| CC vs CT | 0.018 | 5.4 | 1.2 -23.3 |

| Fatty liver | 0.014 | 4.8 | 1.2-13.6 |

| Platelets | 0.005 | 4.7 | 1.3-17.3 |

| Grading | 0.026 | 3.9 | 1.1-13.4 |

| Insulin resistance | 0.029 | 3.9 | 1.1-13.8 |

| HCV viremia | 0.038 | 3 | 1-8.8 |

The study was performed according to ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. All patients were informed about the study, and provided written informed consent.

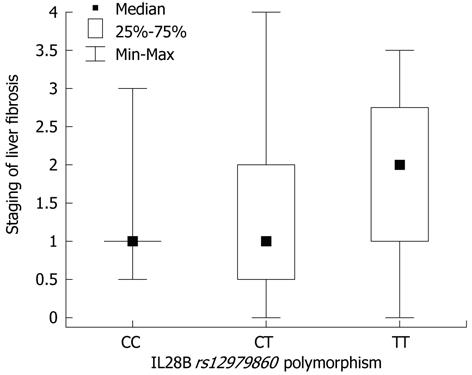

In the Mann-Whitney U test, differences were found in inflammatory-necrotic activity (P = 0.011), stage of fibrosis (P = 0.009), fibrosis progression rate (P = 0.015), EVR and ETR (P = 0.00001), baseline viral load (P = 0.09), reduction in viral load at 3 mo of therapy (P = 0.0004) and the presence of a biochemical response after completion of therapy (P = 0.03) between the patients who achieved a SVR and those who did not. In the group of patients who achieved a SVR, a lower incidence of liver steatosis was observed significantly (χ2 test, P = 0.062). In the χ2 test, there were no significant differences between patients with and without SVR as regards sex, age, comorbidities, and anthropometric factors. Differences in the parameters mentioned above were not observed among the three groups selected on the basis of the IL28B polymorphism. The χ2 test showed differences in the rate of achievement of EVR (P = 0.02), ETR (P = 0.069) and SVR (P = 0.001) between groups of patients with CC, CT and TT alleles. The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test showed differences in the size of the reduction of viral load after 3 mo of therapy (P = 0.019) between groups of patients with CC, CT and TT alleles. The OR revealed that patients with the CC allele had a 25-fold greater chance of achieving a SVR compared with those with the TT allele (P < 0.001) and a 5.4-fold higher chance compared with those with the CT allele (P = 0.018) (Table 2). Patients with low liver inflammation had a 3.9 times greater probability of achieving a SVR (P = 0.026), and patients with no or little fibrosis had 5.9 times greater probability (P = 0.008). HCV viral load < 1 × 106 IU/mL increased the chance of achieving a SVR by 3-fold (P = 0.038), and an IR index < 2.5 increased the chance by 3.9-fold (P = 0.029). The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test showed no differences in the IR index between groups of patients with CC, CT and TT alleles (P = 0.12). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between IR index and stage of fibrosis and BMI was r = 0.618 and r = 0.605, respectively (P < 0.001). In the Mann-Whitney U test, differences were found in the IR index (P = 0.005) between patients with and without steatosis. The Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test revealed borderline significance (P = 0.064) of increased fibrosis in patients with the TT allele (Figure 1).

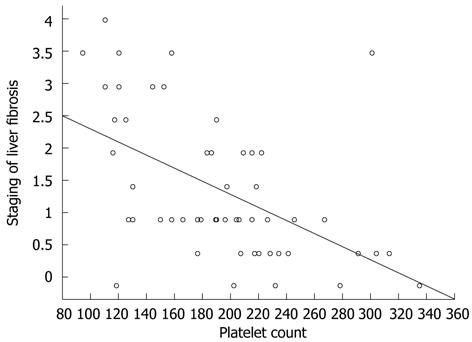

The Mann-Whitney U test established that patients who did not achieve a SVR had low platelet levels at baseline (P = 0.001) compared with subjects with a SVR. A similar trend was also found for neutrophils (P > 0.05). Patients without SVR bearing the CT allele, were characterized by lower baseline platelet count (P = 0.003) and decreased (P = 0.02) drop of platelet count upon treatment. Decreased platelet levels in patients with the CT allele and absence of a SVR were accompanied by a higher incidence of requiring a dose reduction of IFN (P = 0.07). No differences in IFN and RBV dosage in patients with the CT allele or other allelic variants were found between groups with or without a SVR.

The present study observed an impact of IL28B SNPs on the efficacy of IFN and RBV in CHC, which was consistent with the results from previous research. In patients with TT and CT genotypes, greater severity of liver fibrosis and necroinflammation, presence of liver steatosis, higher HCV viral load, and lower baseline platelets, had a reduced chance of therapeutic success. In the OR of the SVR, the greatest differences concerned the IL28B polymorphism between CC and TT alleles. The difference was more than 4-fold for fibrosis in the comparison of the CC allele with the CT allele. For liver steatosis, low platelet level, necroinflammatory grade, IR index and initial viral load of HCV, the difference was 5-8-fold (Table 2). The results confirm that polymorphism in the IL28B is significantly related to the outcome of antiviral therapy of CHC.

The mechanism by which genetic factors influence the progression of fibrosis in CHC remains unclear[18-21]. In the present study, patients with the TT genotype had a more active state of necroinflammation in the histological analysis, and borderline significance (P = 0.06) of greater severity of fibrosis (Figure 1). This observation is consistent with previous results describing a higher incidence of TT or CT allele in cases of cirrhosis and faster fibrosis progression in HCV-infected liver transplant recipients and liver from donors with the TT genotype[16,17]. Taking into consideration that the correlation between the degree of fibrosis and IL28B was not statistically significant and there was no association with fibrosis progression rate, it was not possible to confirm the impact of the genotype on the progress of CHC. Thus, IL28B polymorphism is probably not the factor which directly affects the outcome of untreated CHC.

The correlation between insulin resistance and stage of fibrosis, presence of the liver steatosis, efficacy of IFN/RBV therapy and higher BMI observed in the present study is consistent with the results from previous observations[22-27]. No statistically significant correlation between insulin resistance and IL28B polymorphism was observed, indicating that there are different mechanisms by which both factors can influence the course and therapy of CHC.

In the present study 60% of patients with SVR had TT (8%) or CT (52%) genotypes, which are not known factors associated with higher IFN responsiveness. These values are similar to those described in previous reports[15]. Analysis of the differences in the course of therapy in patients with the CT allele and a SVR revealed higher baseline platelet and neutrophil levels. These factors were markedly reduced in the group of patients with therapeutic failure. The present results are consistent with existing data, where the platelet level was a predictor of a rapid virological response[28]. In this study, a low baseline platelet count was significantly associated with the need for IFN dose reduction in the group without a SVR. In the group of patients with the CT allele, the platelet count was the only factor differentiating patients with and without a SVR. The chance of a SVR was 8-fold higher in patients with the CT allele and higher platelet count compared with patients with low levels of platelets.

The platelet level is one of the factors used to estimate the risk of the presence of advanced liver fibrosis[29]. In the present study, the platelet level also correlated with the stage of liver fibrosis (Figure 2). More severe fibrosis, and a lower baseline platelet level increased the risk of requiring a reduction in IFN dose and subsequent reduction in the chance of achieving a SVR[13]. Assessment of the platelet level and the IL28B polymorphism can complement the decision-making algorithm for a patient’s eligibility for antiviral therapy.

Differentiation of SNPs in the IL28B promoter region is the strongest factor determining the effectiveness of therapy with IFN and RBV. Despite the greater severity of fibrosis in patients with the TT genotype, there was no additional evidence of an IL28B SNP associated with progression of CHC. In patients with the IL28B CT allele, a low baseline platelet count is associated with a requirement to reduce IFN and a decreased chance of obtaining a SVR.

Ineffective therapy for chronic viral hepatitis type C (CHC) determines the progression of liver disease to cirrhosis and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the IL28B promoter gene region determines spontaneous and induced clearance of hepatitis C virus.

Clinical aspects of the impact of IL28B SNPs on the efficacy of antiviral therapy and progression of CHC are not fully recognized. In the present study, potential factors influencing the efficacy of therapy in relation to IL28B polymorphism were investigated.

The results of the study confirm a significant role of SNPs in the IL28B gene among different predictive factors of a sustained virological response (SVR). The impact of IL28B SNPs on the SVR is not related to insulin resistance. In the case of the CT allele, a low baseline platelet count is associated with a reduced chance of a SVR. The phenomenon is connected with the stage of liver fibrosis and need for a reduction of interferon dose during therapy. The results suggest that the progression of CHC is faster in patients with the TT genotype.

Results of the study can complement the decision-making algorithm for eligibility of patients with CHC for antiviral therapy.

Single nucleotide polymorphism is a variation of a single nucleotide usually found in non-coding microsatellite fragments of the genome. It may serve as the fingerprint for predicting susceptibility toward disease. IL28B SNPs include different variants localized in the gene promoter region, among which the most common in clinical practice is C/T SNP of rs 12979860.

This study examined the association of SNPs of the IL28B, rs12979860 on progression of CHC. They found that SNPs of IL28B had any impact on CHC progression, in spite of apparently more advanced fibrosis among patients carrying TT genotype. In addition, they revealed that, in patients with the CT allele IL28B, low baseline platelets count is linked to the reduction of IFN and decreased chance of reaching the SVR. This study demonstrated a new characteristic of IL-28b in CHC.

Peer reviewer: Takumi Kawaguchi, MD, PhD, Department of Digestive Disease Information and Research, Kurume University School of Medicine, 67 Asahi-machi, Kurume 830-0011, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2776] [Cited by in RCA: 2722] [Article Influence: 170.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell E. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1505] [Cited by in RCA: 1503] [Article Influence: 93.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rauch A, Kutalik Z, Descombes P, Cai T, Di Iulio J, Mueller T, Bochud M, Battegay M, Bernasconi E, Borovicka J. Genetic variation in IL28B is associated with chronic hepatitis C and treatment failure: a genome-wide association study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1338-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, Korenaga M, Hino K, Hige S. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1779] [Cited by in RCA: 1774] [Article Influence: 110.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, Ge D, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Urban T, Afdhal NH, Jacobson IM, Esteban R. Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:120-9.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Imazeki F, Yokosuka O, Omata M. Impact of IL-28B SNPs on control of hepatitis C virus infection: a genome-wide association study. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:497-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahlenstiel G, Booth DR, George J. IL28B in hepatitis C virus infection: translating pharmacogenomics into clinical practice. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:903-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pagliaccetti NE, Eduardo R, Kleinstein SH, Mu XJ, Bandi P, Robek MD. Interleukin-29 functions cooperatively with interferon to induce antiviral gene expression and inhibit hepatitis C virus replication. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30079-30089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Tokunaga K, Mizokami M. lambda-Interferons and the single nucleotide polymorphisms: A milestone to tailor-made therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:449-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miller DM, Klucher KM, Freeman JA, Hausman DF, Fontana D, Williams DE. Interferon lambda as a potential new therapeutic for hepatitis C. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1182:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Witte K, Witte E, Sabat R, Wolk K. IL-28A, IL-28B, and IL-29: promising cytokines with type I interferon-like properties. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:237-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Doyle SE, Schreckhise H, Khuu-Duong K, Henderson K, Rosler R, Storey H, Yao L, Liu H, Barahmand-pour F, Sivakumar P. Interleukin-29 uses a type 1 interferon-like program to promote antiviral responses in human hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2006;44:896-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Clark PJ, Thompson AJ, McHutchison JG. IL28B genomic-based treatment paradigms for patients with chronic hepatitis C infection: the future of personalized HCV therapies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Romero-Gomez M, Eslam M, Ruiz A, Maraver M. Genes and hepatitis C: susceptibility, fibrosis progression and response to treatment. Liver Int. 2011;31:443-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Charlton MR, Thompson A, Veldt BJ, Watt K, Tillmann H, Poterucha JJ, Heimbach JK, Goldstein D, McHutchison J. Interleukin-28B polymorphisms are associated with histological recurrence and treatment response following liver transplantation in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2011;53:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fabris C, Falleti E, Cussigh A, Bitetto D, Fontanini E, Bignulin S, Cmet S, Fornasiere E, Fumolo E, Fangazio S. IL-28B rs12979860 C/T allele distribution in patients with liver cirrhosis: role in the course of chronic viral hepatitis and the development of HCC. J Hepatol. 2011;54:716-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bataller R, North KE, Brenner DA. Genetic polymorphisms and the progression of liver fibrosis: a critical appraisal. Hepatology. 2003;37:493-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Poynard T, Bedossa P, Opolon P. Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. The OBSVIRC, METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet. 1997;349:825-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2199] [Cited by in RCA: 2159] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alberti A, Chemello L, Benvegnù L. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1999;31 Suppl 1:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Perumalswami P, Kleiner DE, Lutchman G, Heller T, Borg B, Park Y, Liang TJ, Hoofnagle JH, Ghany MG. Steatosis and progression of fibrosis in untreated patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology. 2006;43:780-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Romero-Gómez M, Del Mar Viloria M, Andrade RJ, Salmerón J, Diago M, Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Corpas R, Cruz M, Grande L, Vázquez L. Insulin resistance impairs sustained response rate to peginterferon plus ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:636-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 539] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Petta S, Cammà C, Di Marco V, Alessi N, Cabibi D, Caldarella R, Licata A, Massenti F, Tarantino G, Marchesini G. Insulin resistance and diabetes increase fibrosis in the liver of patients with genotype 1 HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1136-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cua IH, Hui JM, Kench JG, George J. Genotype-specific interactions of insulin resistance, steatosis, and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2008;48:723-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kawaguchi T, Taniguchi E, Itou M, Sakata M, Sumie S, Sata M. Insulin resistance and chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Cammà C, Petta S, Di Marco V, Bronte F, Ciminnisi S, Licata G, Peralta S, Simone F, Marchesini G, Craxì A. Insulin resistance is a risk factor for esophageal varices in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;49:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Basaranoglu M, Basaranoglu G. Pathophysiology of insulin resistance and steatosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4055-4062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hayes CN, Kobayashi M, Akuta N, Suzuki F, Kumada H, Abe H, Miki D, Imamura M, Ochi H, Kamatani N. HCV substitutions and IL28B polymorphisms on outcome of peg-interferon plus ribavirin combination therapy. Gut. 2011;60:261-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, Enders F, Saksena S, Burt AD, Bida JP. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology. 2007;45:846-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1917] [Cited by in RCA: 2279] [Article Influence: 126.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |