Published online Sep 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4604

Revised: April 13, 2012

Accepted: April 20, 2012

Published online: September 7, 2012

AIM: To investigate optimal timing for therapeutic efficacy of entecavir for acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACLF-HBV) in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative patients.

METHODS: A total of 109 inpatients with ACLF-HBV were recruited from the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University from October 2007 to October 2010. Entecavir 0.5 mg/d was added to each patient’s comprehensive therapeutic regimen. Patients were divided into three groups according to model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score: high (≥ 30, 20 males and 4 females, mean age 47.8 ± 13.5 years); intermediate (22-30, 49 males and 5 females, 45.9 ± 12.4 years); and low (≤ 22, 28 males and 3 females, 43.4 ± 9.4 years). Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 11.0 software. Data with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD and comparisons were made with Student’s t tests. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Viral loads were related exponentially and logarithmic data were used for analysis.

RESULTS: For 24 patients with MELD score ≥ 30, treatment lasted 17.2 ± 16.5 d. Scores before and after treatment were significantly different (35.97 ± 4.87 and 40.48 ± 8.17, respectively, t = -2.762, P = 0.011); HBV DNA load was reduced (4.882 ± 1.847 copies log10/mL to 3.685 ± 1.436 copies log10/mL); and mortality rate was 95.83% (23/24). Of 54 patients with scores of 22-30, treatment lasted for 54.0 ± 43.2 d; scores before and after treatment were 25.87 ± 2.33 and 25.82 ± 13.92, respectively (t = -0.030, P = 0.976); HBV DNA load decreased from 6.308 ± 1.607 to 3.473 ± 2.097 copies log10/mL; and mortality was 51.85% (28/54). Of 31 patients with scores ≤ 22, treatment lasted for 66.1 ± 41.9 d; scores before and after treatment were 18.88 ± 2.44 and 12.39 ± 7.80, respectively, (t = 4.860, P = 0.000); HBV DNA load decreased from 5.841 ± 1.734 to 2.657 ± 1.154 copies log10/mL; and mortality was 3.23% (1/31).

CONCLUSION: For HBeAg-negative patients with ACLF-HBV, when entecavir was added to comprehensive therapy, a MELD score ≥ 30 predicted very poor prognosis due to fatal liver failure.

- Citation: Yan Y, Mai L, Zheng YB, Zhang SQ, Xu WX, Gao ZL, Ke WM. What MELD score mandates use of entecavir for ACLF-HBV HBeAg-negative patients? World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(33): 4604-4609

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i33/4604.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4604

Currently, there are only four commercially available nucleoside analogs for the treatment of hepatitis B virus (HBV). These include lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir and telbivudine; all efficient antiviral agents that can reduce the HBV DNA load to the lower limit of detection in 72%, 51%, 90% and 88% of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients, respectively, after 1 year of treatment[1-5]. However, these drugs seem to be ineffective for some patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACLF-HBV), for whom even comprehensive therapy in combination with antiviral treatment cannot reduce a high mortality rate[6,7]. When compared with HBeAg-positive CHB patients, the proportion of HBeAg-negative CHB patients has been increasing during recent years, and the age of these patients is relatively advanced. Although the HBV-DNA load is relatively low, this form of hepatitis is active, prone to fluctuation, and positively correlated with the degree of inflammation and necrosis of the liver[8,9]. Furthermore, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are more prevalent among these patients. In a previously reported study, 71.74% of patients with ACLF-HBV were negative for HBeAg[6]. Here, we evaluated the efficacy of entecavir, a potent antiviral nucleoside analog, in ACLF-HBV patients having different model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores, and suggest a new method for guiding the therapeutic decision-making process.

A total of 109 inpatients with ACLF-HBV were recruited from the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University from October 2007 to October 2010. Diagnosis was based on the Guidelines for Diagnosis of Liver Failure (2006)[10] and included the presence of two or more of the following: prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT-INR) ≥ 1.5; serum total bilirubin > 10 times the upper limit of normal; ascites; hepatic encephalopathy; decreased liver size; or the hepatorenal syndrome. The standard serum creatinine (Cr) was defined as the normal median (31.8-93.7 μmol/L), and MELD scores were ≥ 16.1. All patients were hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive, HBeAg-negative, hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb)-positive and hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb)-positive. There were 97 male (89.0%) and 12 female (11.0%) patients with a mean age of 45.61 ± 11.90 years (range: 25-73 years). Patients were divided into three groups according to MELD score: high (≥ 30, 20 male and 4 female, mean age 47.8 ± 13.5 years); intermediate (22-30, 49 male and 5 female, 45.9 ± 12.4 years); and low (≤ 22, 28 male and 3 female, 43.4 ± 9.4 years). There were no marked differences in age and sex among the three groups. Patients co-infected with hepatitis A, C or E virus or human immunodeficiency virus were excluded. None had been treated with regular pegylated interferon, nucleoside analogs, or thymosin. Entecavir 0.5 mg/d was added to each patient’s comprehensive therapeutic regimen as the sole antiviral agent.

HBV DNA levels were determined by real-time polymerase chain reactions with commercial diagnostic kits (Da-an GeneCo., Guangzhou, China). The lower detection limit was 500 copies/mL. HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb and HBcAb were detected with an automatic rapid immunoassay system (AxSYM; Abbott, United States). Total bilirubin and Cr and were measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer (AU 640; Olympus, Japan); normal ranges were 4-17.1 μmol/L and 31.8-93.7 μmol/L, respectively. PT-INR = (prothrombin time/reference prothrombin time) ISI. Prothrombin time was measured using detection reagent STA-Neoplastine(r) CI PLUS with an automatic coagulometer (STA-R) (Diagnostica Stago, France). Sample collection, transportation, preservation and processing were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MELD score = 3.8 × loge [serum bilirubin (μmol/L) × 0.058] + 11.2 × loge (PT-INR) + 9.6 × loge [serum Cr (μmol/L) × 0.011] + 6.4 × (0 or 1) (cholestatic or alcoholic cirrhosis: 0; other liver diseases: 1)[11].

Survival: patients discharged with no evidence of liver failure; death: progression of disease leading to death in spite of comprehensive therapy and entecavir treatment.

Statistical analysis were performed using SPSS 11.0 software. Data with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD and comparisons were made with Student’s t tests. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Viral loads were related exponentially and logarithmic data were used for analysis.

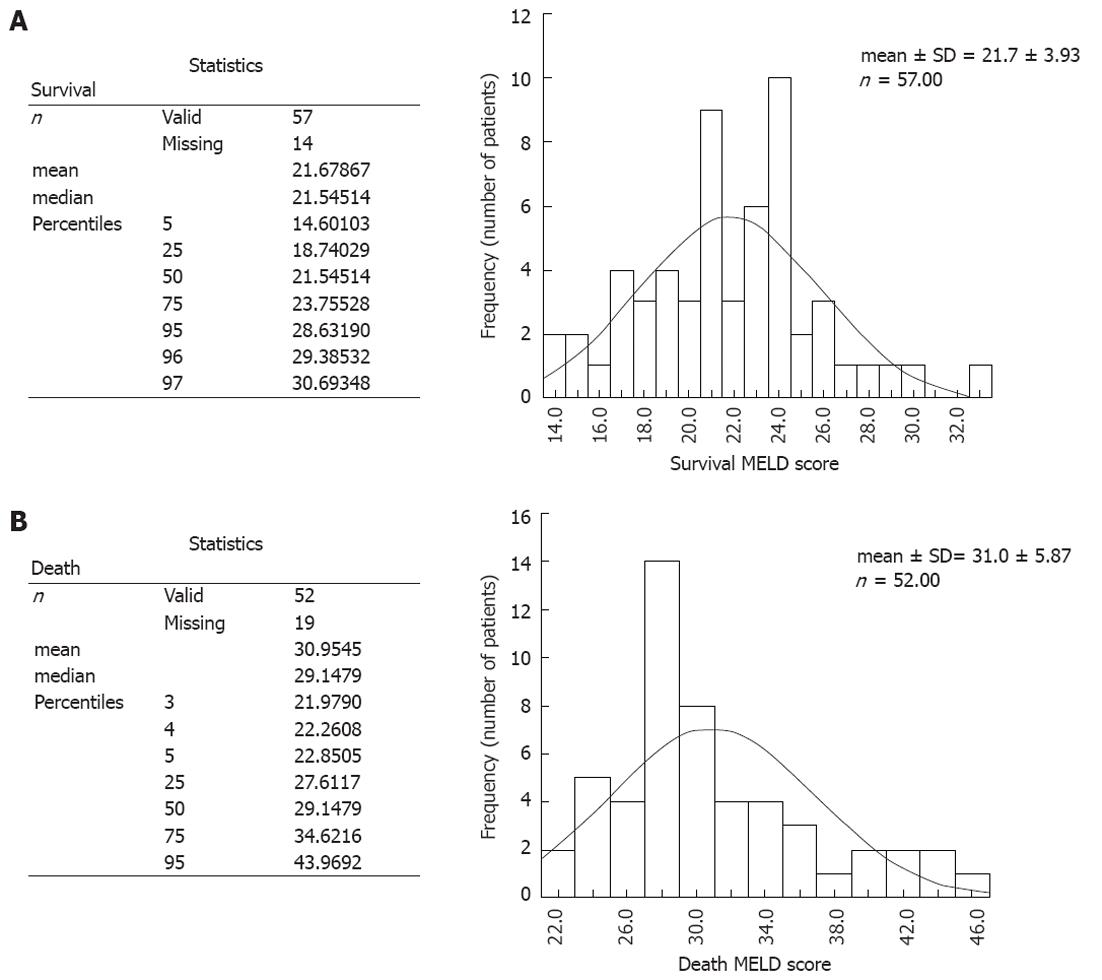

The mortality rate was > 95% in patients with MELD score > 30, and > 95% of patients survived with MELD score < 22. Frequency distribution of MELD scores of patients receiving entecavir who survived or succumbed is described in Figure 1.

Of the 24 patients with high MELD scores (≥ 30), 23 (95.83%) died. Antiviral treatment was administered for 17.2 ± 16.5 d. Comparing measurements taken before antiviral treatment and before death, there were no marked differences in HBV DNA load, total bilirubin, INR and prothrombin activity (PTA), but Cr and MELD scores increased significantly (P = 0.003 and 0.011, respectively) (Table 1).

| n = 24 | Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | INR | Prothrombin activity (%) | Blood creatinine (μmol/L) | MELD score | HBV DNA loads (copies log10/mL) | Treatment course (d) | Mortality (%) |

| High model (n = 24) | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 563.8 ± 163.0 | 4.14 ± 1.05 | 21.2 ± 5.8 | 124.0 ± 113.1 | 35.97 ± 4.87 | 4.882 ± 1.847 | 17.2 ± 16.5 | 95.83 (23/24) |

| Before death | 615.3 ± 216.4 | 4.67 ± 1.71 | 20.0 ± 8.1 | 179.1 ± 129.1b | 40.48 ± 8.17 | 3.685 ± 1.436 | ||

| t value | -1.742 | -1.699 | 0.738 | -3.340 | -2.762 | 2.590 | ||

| P value | 0.095 | 0.103 | 0.468 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.027 | ||

| Intermediate model (n = 54) | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 444.5 ± 160.3 | 2.56 ± 0.71 | 35.6 ± 12.1 | 70.1 ± 15.8 | 25.87 ± 2.33 | 6.308 ± 1.607 | 54.0 ± 43.2 | 51.85 (28/54) |

| After treatment | 409.5 ± 357.7 | 3.23 ± 2.26 | 38.4 ± 24.1 | 93.4 ± 75.8 | 25.82 ± 13.92 | 3.473 ± 2.097b | ||

| t value | 0.667 | -2.637 | -1.132 | -2.223 | -0.030 | 8.826 | ||

| P value | 0.508 | 0.011 | 0.263 | 0.031 | 0.976 | 0.000 | ||

| Low model (n = 31) | ||||||||

| Before treatment | 351.9 ± 114.8 | 1.59 ± 0.37 | 56.8 ± 14.1 | 62.5 ± 11.1 | 18.88 ± 2.44 | 5.741 ± 1.734 | 66.1 ± 41.9 | 3.23 (1/31) |

| Recovery stage | 102.8 ± 144.4 | 1.55 ± 0.64 | 63.5 ± 18.2 | 67.4 ± 52.6 | 12.39 ± 7.80 | 2.657 ± 1.154 | ||

| t value | 7.065 | 0.411 | -2.468 | -0.526 | 4.860 | 9.332 | ||

| P value | 0.000 | 0.684 | 0.020 | 0.603 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

Of the 54 patients with intermediate MELD scores, 28 (51.85%) died and 26 survived. Antiviral treatment was administered for 54.0 ± 43.2 d. The MELD scores before and after antiviral treatment were not significantly different (25.87 ± 2.33 and 25.82 ± 13.92, respectively; t = -0.030, P = 0.976), but the HBV DNA load decreased significantly, by 2.918 ± 1.811 copies log10/mL (P = 0.000). Liver function results and outcomes are presented in Table 1.

There were 31 patients with low MELD scores; one (3.23%) died and 30 survived. Antiviral treatment was administered for 66.1 ± 41.9 d. Total bilirubin decreased and PTA increased significantly during antiviral treatment (P < 0.05), and decreases in MELD score (18.88 ± 2.44 to 12.39 ± 7.80; t = 4.860, P = 0.000) and HBV DNA levels (by 3.185 ± 1.740 copies log10/mL, P = 0.000) were also significant (Table 1).

Providing comprehensive treatment is the main therapeutic strategy for patients with ACLF; when possible other treatment options include use of bioartificial liver support systems and liver transplantation. Comprehensive treatment can only prolong survival for the fraction of patients having a potential for liver regeneration. When antiviral treatment is added, prolonged survival times can be achieved at low cost. It remains controversial whether comprehensive therapy with bioartificial liver support systems is translated into a survival benefit. Liver transplantation is usually limited by high cost, insufficient donors, and unclear effects on long-term survival. In recent years, treatment of liver failure with stem cell transplantation has achieved favorable outcomes in preclinical studies, but this strategy has not been approved and its therapeutic efficacy remains to be confirmed. At present, treatment with nucleoside analogs has been applied in the treatment of ACLF-HBV and has been confirmed effective, but not all patients can survive[12-16]. When is the right time to add nucleoside analogs for treatment of ACLF-HBV patients? Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of comprehensive therapy in combination with antiviral treatment.

For HBeAg-negative and -positive CHB patients, there are differences in indication for treatment with nucleoside analogs, their therapeutic efficacy, and criteria for discontinuation of treatment. In the natural course of CHB, the HBV viral load significantly increases once the host immune function is compromised, which may induce acute cellular immune responses, resulting in ACLF. Therefore, maximizing long-term inhibition or elimination of HBV DNA may prevent the occurrence of ACLF in HBeAg-negative patients[17]. Nucleoside analogs can rapidly inhibit the replication of HBV and minimize propagation of the virus between hepatocytes. In addition, antiviral treatment can reduce target antigens on hepatocytes, thereby reducing attacks by cytotoxic T cells, thus attenuating the extent of damage and subsequent necrosis.

Entecavir is a cyclopentyl guanosine analog that can significantly inhibit HBV DNA polymerase, which then suppresses initiation of DNA replication and extension, resulting in reduction of viral load[18-20]. Among four commercially available nucleoside analogs, entecavir is the most potent antiviral drug, and it has the lowest frequency of resistance (1% after 4 years)[21,22]. The US Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B recommends entecavir as the first-line antiviral drug for treatment of patients with HBV-related liver failure[23]. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the efficacy of entecavir in combination with comprehensive therapy of ACLF-HBV, according to MELD score.

In 2003, Malinchoc et al[11] analyzed clinical information of 231 patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt procedures. They applied Cox proportional hazards regression to establish the MELD score, which was then used to evaluate the risk of death among patients with liver diseases of any cause, achieving favorable reliability. A 2002 study revealed that MELD scores were given priority in making the decision to perform liver transplantation[24]. In addition, MELD score is also a sensitive indicator of the severity of liver failure.

In the present study, mean scores in the high MELD score group increased significantly before death, and mortality was 95.83% (23/24). Therapeutic failure in this group may be attributed to the fact that suppression of viral replication requires a relative long period of time; a previous study has determined that treatment with entecavir can significantly reduce the viral load within 4 wk[25]. However, treatment in this group lasted on average only 17.2 d, in the setting of fatal liver failure. In addition, ACLF pathogenesis is complex; the rapid increase in HBV replication is only one factor contributing to liver failure. Once liver failure is initiated, additional antiviral treatment is not adequate to prevent progression.

No significant differences in scores were observed before and after antiviral treatment in the intermediate MELD score group, which may account for the difference in outcome [48.15% (26/54) recovered and 51.85% (28/54) died]. Death in this group may be related to late-stage ACLF or to deteriorating liver function in the early or intermediate stages. In this CHB condition, massive liver necrosis may occur from induction of potent cellular immune responses; as a result, antiviral treatment may not be effective. Survival of 48.15% (26/54) of these patients may be attributed to the potential for liver regeneration, even if several parameters suggest liver failure. In this group, the course of treatment was 54.0 d, so HBV DNA replication was significantly suppressed, and further liver necrosis was prevented.

In the low MELD score group, scores were significantly decreased by antiviral treatment, and the mortality was 3.23% (1/31). The majority of patients recovered, possibly because they had early-stage ACLF, a low risk for development of cellular immune responses, and the potential for compensatory liver regeneration. The mean length of treatment was 66.1 d; enough time for entecavir to accomplish an antiviral effect, which, together with effective liver regeneration, promotes recovery from liver failure.

We suggest that timely administration of an antiviral agent may improve prognosis for HBeAg-negative ACLF patients, and that prognosis can be predicted by the MELD score. When the score is ≤ 22, most patients may survive if given comprehensive therapy in combination with antiviral treatment. When the MELD is 22-30, survival, if given antiviral treatment, will depend on the severity of liver failure, the developmental trend of the disease, and whether comprehensive therapeutic interventions provide enough time for antiviral drugs to exert their effects. When the MELD score is ≥ 30, the vast majority of patients will not recover with comprehensive plus antiviral therapy. These patients are at high risk for death and liver transplantation should be considered.

In the natural course of chronic hepatitis B, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) viral load significantly increases once the host immune function is compromised, which may induce acute cellular immune responses, resulting in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). Therefore, maximizing long-term inhibition or elimination of HBV DNA may prevent the occurrence of ACLF in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-negative patients.

In previous studies, treatment with nucleoside analogs has been used for acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure (ACLF-HBV) and has been confirmed as effective. When is the right time to add nucleoside analogs to treatment of ACLF-HBV patients? The present study investigated the optimal timing, according to model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, for therapeutic efficacy of entecavir for ACLF-HBV in HBeAg-negative patients.

For HBeAg-negative patients with ACLF-HBV, when entecavir was added to comprehensive therapy, patients with different MELD scores may have a different outcome; a MELD score ≥ 30 predicted very poor prognosis due to fatal liver failure.

This issue is of great interest and is offering a new method of deciding the optimal timing for therapeutic efficacy of entecavir to treat ACLF-HBV in HBeAg-negative patients according to MELD score.

Peer reviewer: Tatsuya Ide, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Kurume University School of Medicine, 67 Asahi-machi, Kurume 830-0011, Japan

S- Editor Lv S L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, Farci P, Hadziyannis S, Jin R, Lu ZM, Piratvisuth T, Germanidis G, Yurdaydin C. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1206-1217. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Zink RC, Cross A. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011-1020. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tassopoulos NC, Volpes R, Pastore G, Heathcote J, Buti M, Goldin RD, Hawley S, Barber J, Condreay L, Gray DF. Efficacy of lamivudine in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-negative/hepatitis B virus DNA-positive (precore mutant) chronic hepatitis B. Lamivudine Precore Mutant Study Group. Hepatology. 1999;29:889-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576-2588. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Shu X, Xu QH, Chen N, Zhang K, Li G. [The clinic features and the short-term efficacy of entecavir treatment of the HBeAG negative acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure]. Zhonghua Shiyan He Linchuang Bingduxue Zazhi. 2008;22:481-483. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shu X, Xu QH, Chen N, Zhang K, Li G. [The clinic features and the short-term efficacy of entecavir treatment of the HBeAG negative acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure]. Zhonghua Shiyan He Linchuang Bingduxue Zazhi. 2008;22:481-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Coco B, Leandro G, Colombatto P, Gorin JM, Bonino F. Outcome of anti-HBe positive chronic hepatitis B in alpha-interferon treated and untreated patients: a long term cohort study. J Hepatol. 2002;36:263-270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Lindh M, Horal P, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G. Hepatitis B virus DNA levels, precore mutations, genotypes and histological activity in chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2000;7:258-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association, Severe Liver Diseases and Artificial Liver Group. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for liver failure. Zhonghua Chuan Ran Bing Zazhi. 2006;24:422-425. |

| 11. | Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1967] [Cited by in RCA: 2069] [Article Influence: 82.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chen LB, Cao H, Zhang YF, Shu X, Chen N, Zhang K, Li G, Xu QH. [Efficacy of antiviral treatment on patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure with low viral load]. Zhonghua Shiyan He Linchuang Bingduxue Zazhi. 2010;24:364-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sun LJ, Yu JW, Zhao YH, Kang P, Li SC. Influential factors of prognosis in lamivudine treatment for patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu JW, Sun LJ, Zhao YH, Li SC. Prediction value of model for end-stage liver disease scoring system on prognosis in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure after plasma exchange and lamivudine treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1242-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Janssen HL, van Zonneveld M, Senturk H, Zeuzem S, Akarca US, Cakaloglu Y, Simon C, So TM, Gerken G, de Man RA, Niesters HG, Zondervan P, Hansen B, Schalm SW. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b alone or in combination with lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sun QF, Ding JG, Xu DZ, Chen YP, Hong L, Ye ZY, Zheng MH, Fu RQ, Wu JG, Du QW. Prediction of the prognosis of patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure using the model for end-stage liver disease scoring system and a novel logistic regression model. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoshiba M. [Recent advances in the treatment of fulminant hepatitis B]. Nihon Rinsho. 2004;62 Suppl 8:280-283. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Honkoop P, De Man RA. Entecavir: a potent new antiviral drug for hepatitis B. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:683-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1107] [Cited by in RCA: 1090] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Levine SM, Pokornowski KA, Walsh AW, Fang J, Yu CF, Zhang S, Mazzucco CE. Two-year assessment of entecavir resistance in Lamivudine-refractory hepatitis B virus patients reveals different clinical outcomes depending on the resistance substitutions present. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:902-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yao GB, Zhu M, Wang YM, Xu DZ, Tan DM, Chen CW, Hou JL. A double-blind, double-dummy, randomized, controlled study of entecavir versus lamivudine for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Zhanghua Neike Zazhi. 2006;45:891-895. |

| 22. | Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, Walsh A, Fang J, Hsu M, Mazzucco C. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naïve patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:1656-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, Tobias H, Wright TL. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:936-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D'Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3462] [Cited by in RCA: 3677] [Article Influence: 153.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yao G. Entecavir is a potent anti-HBV drug superior to lamivudine: experience from clinical trials in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |