Published online Sep 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4549

Revised: March 29, 2012

Accepted: May 12, 2012

Published online: September 7, 2012

AIM: To investigate the prognostic value of CD44 variant 6 (CD44v6), a membranous adhesion molecule, in rectal cancer.

METHODS: Altogether, 210 rectal cancer samples from 214 patients treated with short-course radiotherapy (RT, n = 90), long-course (chemo) RT (n = 53) or surgery alone (n = 71) were studied with immunohistochemistry for CD44v6. The extent and intensity of membranous and cytoplasmic CD44v6 staining, and the intratumoral membranous staining pattern, were analyzed.

RESULTS: Membranous CD44v6 expression was seen in 84% and cytoplasmic expression in 81% of the cases. In 59% of the tumors with membranous CD44v6 expression, the staining pattern in the invasive front was determined as “front-positive” and in 41% as “front-negative”. The latter pattern was associated with narrower circumferential margin (P = 0.01), infiltrative growth pattern (P < 0.001), and shorter disease-free survival in univariate survival analysis (P = 0.022) when compared to the “front-positive” tumors.

CONCLUSION: The lack of membranous CD44v6 in the rectal cancer invasive front could be used as a method to identify patients at increased risk for recurrent disease.

- Citation: Avoranta ST, Korkeila EA, Syrjänen KJ, Pyrhönen SO, Sundström JTT. Lack of CD44 variant 6 expression in rectal cancer invasive front associates with early recurrence. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(33): 4549-4556

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i33/4549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4549

In 2008, approximately 1.2 million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) were diagnosed globally[1]. Preoperative radiotherapy (RT) for rectal cancer has improved local control rates[2], but patients may still present with fairly differing clinical responses and prognoses[3]. To improve disease predictability, strong expectations have been placed on tumor markers.

CD44 is a family of transmembrane glycoproteins serving as a major receptor for hyaluronate, an important component of the extracellular matrix (ECM)[4]. CD44 has been suggested to act both as a tumor-suppressing cofactor and as a growth- and invasiveness-promoting molecule[5] through its participation in many important cellular processes, including adhesion, growth regulation, survival, differentiation and motility[6]. Of the several isoforms produced by alternative splicing of the CD44 gene[7], variant 6 (CD44v6) has been intensely studied in relation to CRC progression and outcome[8].

Induction in CD44v6 expression is suggested to represent an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis[9], and has in some studies been related to disease progression, metastatic potential[7,9,10], and poor disease outcome[11]. Instead, in some other studies, stronger CD44v6 expression has been reported in adenomas than in carcinomas, as well as in primary carcinomas compared to metastatic tumors[12], and has been shown to have favorable[8,13] or no[14] effect on CRC outcome. Furthermore, strong expression has been shown to indicate more favorable response to chemotherapy[15].

In most of the previous studies on CD44v6 expression in colorectal tumors, both colonic and rectal carcinomas have been included. There is, however, some evidence that proximal and distal colonic lesions differ in their expression of CD44v6[16]. In those few studies including solely rectal tumors[17-19], CD44v6 has not been considered in relation to RT. In the present study, we examined the expression of CD44v6 immunohistochemically in a cohort of 214 primary rectal carcinomas treated with or without preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy. Considering the fundamental role of the tumor invasive front in tumor-host interaction[20], as well as the discrepant data on the prognostic value of the extent of CD44v6 expression in CRC[8,11,14], intratumoral staining pattern of this protein was also systematically assessed. We hypothesized that this aspect could offer additional information of the significance of CD44v6 expression in rectal cancer.

The material of this study consisted of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples from 214 patients operated upon for rectal cancer at Turku University Hospital between 2000 and 2009. Operative samples were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology, Turku University Hospital. To ensure a biologically and therapeutically homogeneous study population, only tumors of the middle and lower rectum were included. Superficial tumors treated with excision only, as well as patients with distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, were excluded. The use of archival tissue material was approved by the National Supervisory Authority for Welfare and Health (permission No. Dnro 1709/32/300/02, May 13th 2002).

Tumor staging was done according to the tumor node metastasis classification of malignant tumors, 2002[21]. Selection of treatment was based on preoperative tumor staging which included computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging of the rectum, CT of the abdomen, and X-ray or CT of the chest. According to the common clinical guidelines[22], patients were treated either with short-course preoperative RT (n = 90), long-course preoperative (chemo) RT (n = 53), or received no treatment before surgery (n = 71). Short-course RT consisted of five 5-Gy fractions during 1 wk, with surgery on the following week. Long-course RT was given in 1.8-Gy fractions to a total dose of 50.4 Gy over a 6-wk period, with (n = 44) or without (n = 9) concomitant chemotherapy, and operation was performed at 5-7 wk after RT. Chemotherapy regimens were either bolus 5-fluorouracil (n = 5) or capecitabine (n = 39). Anterior resection was performed in 118 cases (55%), and abdominoperineal resection in 92 cases (43%). In four cases (2%), some other technique, such as low Hartmann’s procedure, was used. The presence of vascular invasion was assessed in 159 cases, in which cancer cells could be detected in 47 cases (30%), either in the extramural lymphatic or blood vessels. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was given to patients with lymph node positive or high-risk lymph node negative tumors according to the standard clinical practice[22]. The median follow-up time was 45.5 mo. In 61 patients (29%), local or distant disease recurrence was seen. Of them, 39 (64%) were treated with chemotherapy with or without biological treatments. Among these 39 cases, progression-free survival (PFS) was retrospectively defined from the medical records, and the median PFS was 20.7 mo. The key demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

| Clinical characteristics | Short course RT | Long course RT | Control | P1 |

| Study population (n = 214) | ||||

| Male | 57 (63) | 34 (64) | 32 (45) | 0.03 |

| Female | 33 (37) | 19 (36) | 39 (55) | |

| Mean age (yr) | 65.2 | 64.7 | 74.5 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative T | ||||

| T1-2 | 28 (31) | 0 (0) | 22 (31) | |

| T3 | 54 (60) | 2 (4) | 12 (17) | < 0.001 |

| 2T4 | 1 (1) | 50 (94) | 3 (4) | |

| Tx | 7 (8) | 1 (2) | 34 (48) | |

| Postoperative T | ||||

| T1 | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 5 (7) | |

| T2 | 34 (38) | 6 (11) | 26 (37) | |

| T3 | 50 (56) | 27 (51) | 37 (52) | < 0.001 |

| T4 | 3 (3) | 14 (26) | 3 (4) | |

| T0 | 0 | 4 (8) | 0 | |

| Postoperative N | ||||

| N0 | 53 (59) | 36 (68) | 41 (58) | |

| N1 | 26 (29) | 14 (26) | 15 (21) | 0.33 |

| N2 | 11 (12) | 3 (6) | 12 (17) | |

| Nx | 0 | 0 | 3 (4) | |

| Grade | ||||

| G1 | 9 (10) | 10 (19) | 12 (17) | |

| G2 | 58 (64) | 33 (62) | 48 (68) | 0.07 |

| G3 | 21 (23) | 3 (6) | 11 (16) | |

| Gx | 2 (2) | 7 (13) | 0 | |

| 3Crm (mm) | ||||

| 0 | 3 (4) | 11 (25) | 4 (9) | |

| 0 ≤ crm ≤ 2 | 9 (12) | 7 (16) | 7 (16) | 0.009 |

| > 2 | 65 (84) | 26 (59) | 32 (74) | |

| Disease specific outcome | ||||

| Alive without recurrence | 64 (71) | 25 (47) | 39 (55) | |

| Alive with recurrence | 7 (8) | 7 (13) | 4 (6) | 0.07 |

| Died of disease | 11 (12) | 12 (23) | 18 (25) | |

| Died of other causes | 8 (9) | 9 (17) | 10 (14) | |

Four tumors with T0 after long-course RT were not stained, and accordingly, the actual study material consisted of 210 samples. The most representative blocks were selected and cut into 5-μm sections. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating in a microwave oven in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate, pH 6.0 two times for 7 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the slides in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in Tris-buffered saline. The sections were subjected to immunohistochemical staining with monoclonal antibody for CD44v6 (concentration 1:1000; Bender MedSystems, Vienna, Austria) and monoclonal mouse anti-cytokeratin (Ck-Pan) (clone: AE1/AE3, concentration 1:50; Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, United States) using EnVision + Dual Link System - HRP (Dako, Denmark).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was individually evaluated by two observers (Avoranta ST and Sundström JTT) blinded to clinical data. Squamous basal cells of anal epithelium included in some of the cases were used as a positive control for CD44v6. Using 5×, 10× and 20× objectives, the immunostaining of CD44v6 in every slide was assessed using the following parameters: (1) the extent of expression (membranous and cytoplasmic staining scored separately); (2) the intensity of expression (membranous and cytoplasmic staining scored separately); and (3) the intratumoral pattern of membranous CD44v6 expression. The extent of expression within the whole tumor area was analyzed using four categories: 1 for immunopositivity < 5%, 2 for 5%-20%, 3 for 21%-50% and 4 for > 50%. The intensity of expression was analyzed using four categories: 1 for negative staining; 2 for weak staining (a faint immunopositivity in the membrane or cytoplasm); 3 for moderate staining (a clear immunopositivity in the membrane or cytoplasm); and 4 for strong staining (a pronounced immunostaining in the membrane or cytoplasm equivalent to that of the basal cells of anal squamous epithelium). The intratumoral pattern of membranous CD44v6 expression was classified into three categories: 1 for immunopositivity mainly in the tumor invasive front; 2 for immunopositivity mainly in the tumor central areas; and 3 for heterogenous immunopositivity (no apparent difference in CD44v6 expression between the invasive front and central areas of tumor).

For statistical purposes, categories 1 and 2 were studied as one group and categories 3 and 4 as another group when analyzing the extent and intensity of expression. With regard to the intratumoral pattern of membranous staining, categories 1 and 3 were studied as one group (“front-positive”), and category 2 as in its own group (“front-negative”).

In order to evaluate tumor growth pattern, hematoxylin-eosin and Ck-Pan stainings were scrutinized in each operative sample. Using the Jass’ classification of the tumor growth pattern, tumours were appointed as “expanding” when the invasive margin was pushing or reasonably well circumscribed, and “infiltrating” when the tumor invaded in a diffuse manner with widespread penetration into adjacent normal tissues[23].

Tumor regression grade (TRG) after long-course RT was defined by a pathologist (Sundström JTT) as poor, moderate or excellent according to the modified Dworak and Rödel scales, as described recently[24]. Briefly, poor TRG was defined as minimal or no tumor regression after (chemo) RT. In case of poor response, many tumor cells remained after treatment. In tumors with moderate response, there were only some tumor cells or tumor cell groups left in the primary tumor, lymph nodes or perirectal fat. In tumors with excellent response, few or no tumor cells could be detected.

Statistical analysis were run using IBM SPSS® Statistics 19.0.1 for Windows software. Frequency tables were analyzed using the χ2 test, with the likelihood ratio (LR) or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. 2 × 2 tables were used to calculate odds ratio and 95% CI using the exact method. Fisher’s exact test, Spearman’s correlation and LR were used to assess the significance of the correlation between individual variables in univariate analysis. Inter-observer reproducibility of the assessments was tested using weighted κ. It was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) test, in parallel mode with a two-way random model, using consistency assumption and the average-measures option to interpret the ICC (95% CI). The ICC of assessments was very good with weighted κ ranging from 0.70 to 0.90.

Univariate survival analysis for disease-free survival (DFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) was based on the Kaplan-Meier method where stratum-specific outcomes were compared using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) statistics. To adjust for the covariates, a Cox proportional hazards regression model was used, covariates (as listed separately) being inserted using the enter mode. Of the variables significant in univariate analysis, two (circumferential margin, vascular invasion) were not included in the multivariate model because the data were incomplete. All statistical tests were two-sided and declared significant at a P value of < 0.05.

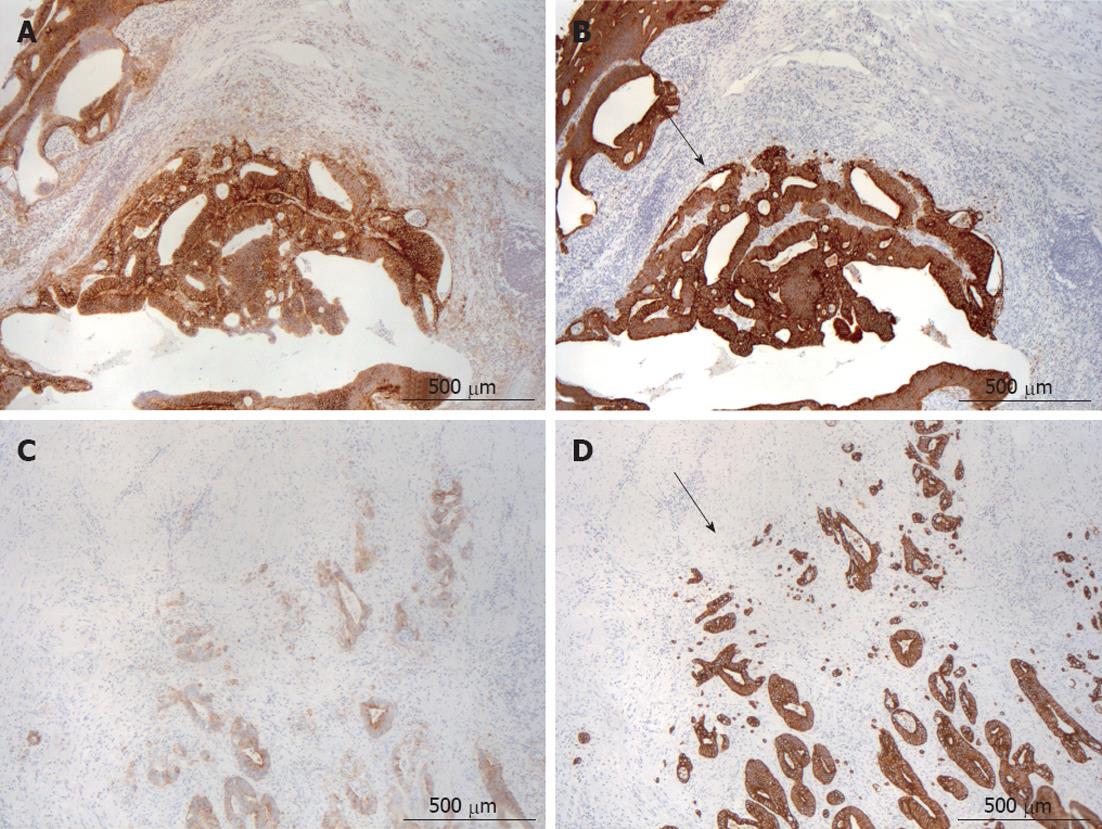

Altogether, 177 out of 210 tumors (84%) showed membranous and 170 (81%) cytoplasmic CD44v6 expression. Both the extent and intensity of membranous and cytoplasmic staining were closely correlated (r = 0.4; r = 0.31, P < 0.001 for both). Of the 177 tumors with membranous CD44v6 positivity, 105 (59%) were “front-positive” (Figure 1A), usually showing an expanding growth pattern (Figure 1B), and 72 (41%) were “front-negative” (Figure 1C), usually showing an infiltrating growth pattern (Figure 1D).

In 206 tumors, a proper invasive front could be detected to evaluate tumor growth pattern. Altogether, 99 (48%) showed an expanding (Figure 1B) and 107 (52%) an infiltrating growth pattern (Figure 1D).

Only the extent of cytoplasmic staining was related to treatment group. Patients in the long-course RT group had less cytoplasmic CD44v6 expression in their tumors as compared to patients in the control group (P = 0.002). Within the long-course RT group, no differences in CD44v6 expression were seen according to concomitant chemotherapy. TRG after long-course RT, as analyzed also from the four tumors without IHC for CD44v6, was poor in 27 cases (51%), moderate in 14 cases (26%) and excellent in 12 cases (23%). No significant differences were seen in CD44v6 expression, as related to TRG.

No significant differences were seen in the extent or intensity of CD44v6 expression concerning the variables listed in Table 1. With regard to the intratumoral pattern of membranous staining, “front-negative” was associated with narrower circumferential margin (P = 0.01), infiltrative tumor growth pattern (P < 0.001), and a greater risk for disease recurrence (P = 0.01 overall) as demonstrated in Table 2. No difference was seen in the number of patients receiving postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy between “front-positive” and “front-negative” groups (P = 0.65). Of the “front-positive” tumors, 37% were diagnosed before and 63% after 2005; the corresponding proportions for “front-negative” tumors being 22% and 78%, respectively (P = 0.035). No other significant correlations were seen between the staining pattern and clinicopathological variables, including PFS.

| Variable (n = 177) | "Front-positive"(n = 105) | "Front-negative"(n = 72) | P1 |

| Treatment group | |||

| Short-course RT | 46 (44) | 32 (44) | |

| Long-course RT | 24 (23) | 14 (19) | 0.87 |

| Control | 35 (33) | 26 (36) | |

| Postoperative T | |||

| T1-2 | 43 (41) | 21 (29) | |

| T3 | 55 (52) | 42 (58) | 0.19 |

| T4 | 7 (7) | 9 (13) | |

| Postoperative N | |||

| N0 | 68 (65) | 40 (56) | |

| N1-2 | 36 (34) | 31 (43) | 0.37 |

| Nx | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| 2Crm | |||

| ≤ 2 mm | 14 (18) | 22 (38) | 0.01 |

| > 2 mm | 64 (82) | 36 (62) | |

| Tumor growth pattern | |||

| Expanding | 63 (60) | 23 (32) | < 0.001 |

| Infiltrating | 42 (40) | 49 (68) | |

| Disease-specific outcome | |||

| Alive without recurrence | 68 (65) | 39 (54) | |

| Alive with recurrence | 3 (3) | 12 (17) | 0.01 |

| Died of disease | 21 (20) | 15 (21) | |

| Died of other causes | 13 (12) | 6 (8) |

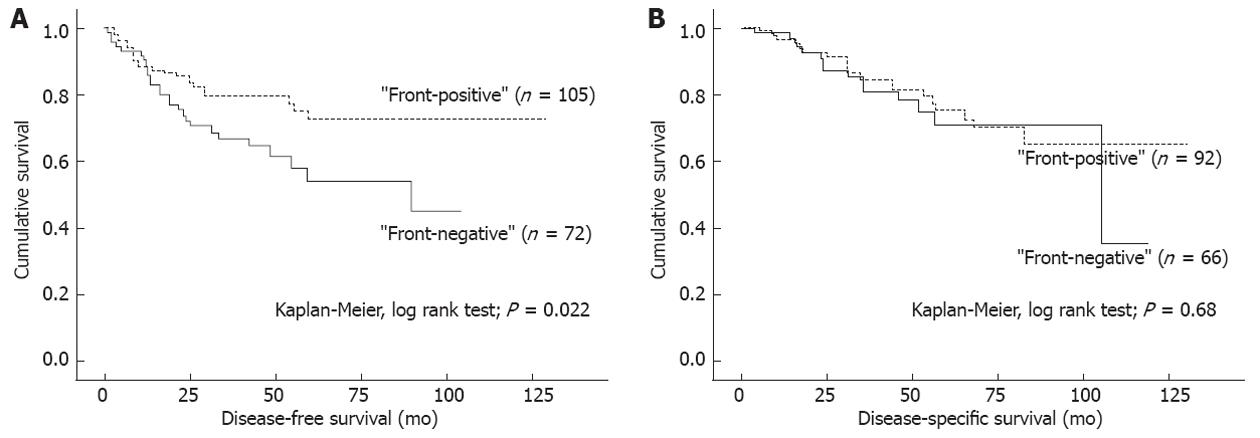

In univariate survival (Kaplan-Meier) analysis, no differences in DFS or DSS were seen according to the extent or intensity of CD44v6 expression, neither membranous nor cytoplasmic (data not shown). DFS (P = 0.022), but not DSS (P = 0.68), in patients with “front-negative” tumors was significantly shorter than in patients with “front-positive” tumors (Figure 2A and B). The same trend/difference was also seen in the short-course RT and control groups (P = 0.058 and P = 0.024 for difference in DFS, respectively) when analyzing treatment subgroups separately. With regard to tumor growth pattern, infiltrating tumors had shorter DFS (P = 0.015), and a tendency towards a shorter DSS (P = 0.14), as compared to expanding tumors.

The results of multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 3. The independent adverse prognostic factors for DFS were male sex, high postoperative T and the presence of positive lymph nodes, and those for DSS were patient age, postoperative T4, poor differentiation grade and disease recurrence.

| Variable | DFS | DSS | ||||

| Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Male | 1.9 | 1.0-3.5 | 0.04 | 1.5 | 0.7-3.0 | 0.3 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 70 yr (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| ≥ 70 yr | 1.4 | 0.8-2.4 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 2.1-10.5 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative T | ||||||

| T1-2 (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| T3 | 3.2 | 1.4-7.2 | 0.005 | 2.0 | 0.8-5.1 | 0.1 |

| T4 | 5.9 | 2.0-17.0 | 0.001 | 4.8 | 1.4-17.0 | 0.02 |

| Postoperative N | ||||||

| N0 (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| N1-2, Nx | 2.0 | 1.1-3.7 | 0.02 | 0.8 | 0.4-1.7 | 0.6 |

| 1Postoperative grade | ||||||

| G1 (ref) | 1.0 | |||||

| G2 | 1.3 | 0.4-3.9 | 0.7 | |||

| G3 | 5.2 | 1.6-17.4 | 0.007 | |||

| Growth pattern | ||||||

| Expanding (ref) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Infiltrating | 1.0 | 0.5-1.8 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.4-1.7 | 0.6 |

| 1CD44v6 staining pattern | ||||||

| “Front-positive” (ref) | 1.0 | |||||

| “Front-negative” | 1.4 | 0.8-2.6 | 0.2 | |||

| Recurrence | ||||||

| No (ref) | 1.0 | |||||

| Yes | 74.3 | 17.0-326.7 | < 0.001 | |||

Loss and gain of adhesive functions play an essential role in the progression of epithelial neoplasms[25]. In the present study, the expression of CD44v6, a cell surface mediator of cell-to-ECM adhesion[4], was systematically studied in a cohort of 214 primary rectal carcinomas treated with or without preoperative RT. The actual extent of CD44v6 expression was not associated with disease progression or outcome, but the analysis of its intratumoral staining pattern showed that patients with “front-negative” staining pattern had a significantly shorter DFS.

In our series, both membranous and cytoplasmic staining of CD44v6 was present in most cases, with a strong mutual correlation as reported earlier[8]. We found that preoperative RT affected cytoplasmic but not membranous CD44v6 expression. Although membranous CD44v6 is known to bind extracellular hyaluronate and growth factors[5], the biological significance of cytoplasmic CD44v6 is rather unknown[8]. In some studies it has been considered to have no functional roles[8], whereas in others, it has been related to neoplastic transformation[12,26] suggesting a role in loss of differentiation[26]. As preoperative RT has been shown to cause remarkable histological alterations[27], the reason for a decrease in cytoplasmic CD44v6 expression after RT could reflect these histological changes. However, further studies are required to elucidate this suggestion.

The prognostic value of CD44v6 expression, regarding the extent of expression, has been studied with inconclusive results in CRC[8,11,14]. In accordance with Morrin et al[14], we found no differences in disease progression indicators and patient outcome according to the extent of CD44v6 expression. This finding is in contrast with some recent studies on rectal tumors, in which high membranous CD44v6 expression was shown to be associated with local recurrence[19] as well as shorter DFS[17-19] and DSS[17,18]. In contrast to these studies, we also included preoperatively treated tumors in our study to assess the possible relation of CD44v6 expression to TRG. This dissimilar study design may explain some of the discrepancy even though we found no differences in membranous CD44v6 expression parameters between the treatment or TRG-groups. In addition, the discrepancy may originate from differences in antibodies, cut-off points as well as disease subtypes in different studies as earlier discussed by Naor et al[28].

In addition to the extent of CD44v6 expression, we also assessed the intratumoral staining pattern of membranous expression. Given that tumor-host interaction at the invasive CRC front is thought to represent a dynamic interface between pro- and antitumor factors[20], it is not surprising that abnormalities in cell adhesion functions are seen in this compartment[29,30]. Although loss of membranous CD44v6 expression towards the CRC invasive front has been reported[8,12], our study is, to our knowledge, the first to assess the relation of membranous CD44v6 staining pattern to rectal cancer outcome. Furthermore, some of the previous studies are based on tissue microarray analyses, questioning the reliability of invasive front detection. Interestingly, “front-negative” tumors were related to more narrow postoperative circumferential margin and infiltrative tumor growth pattern as compared to “front-positive tumors” with apparent CD44v6 expression in the invasive front. Previously, Ishida[31] and Zlobec et al[8] with their co-workers have shown weak/negative CD44v6 expression to be related to infiltrating growth pattern, as assessed by its overall extent irrespective of its localisation. Our results may indicate that more important than the actual quantity of CD44v6 expression is, indeed, its localisation within the tumor. It is possible that “front-negative” tumors are more difficult for surgeon to resect with wide margins as they grow in a more diffuse manner, explaining the more narrow margins seen in these lesions.

Our observations lend support to the view of Zlobec et al[8], and Coppola et al[12], suggesting that the loss of membranous CD44v6 at the advancing edge of the tumor results in defective binding of the tumor cells to ECM, increasing their mobility and metastatic potential[8,12]. Further supporting this view, treatment with hyaluronic acid has recently been shown to delay the growth of residual colon carcinoma cells after chemotherapy[32]. Indeed, CD44v6 is known to have a higher affinity for hyaluronate, as compared to standard CD44[33], and, CD44v6-expressing tumors cells could be more effectively entrapped within the hyaluronic acid at the primary site[12]. In addition to binding with extracellular hyaluronate, membranous CD44v6 expression in the invasive front may also be important due to its intercellular adhesion properties, because loss of CD44v6 expression has been correlated to the loss of E-cadherin expression[8].

Importance of the localization of CD44v6 expression was further supported by the fact that “front-negative” tumors more often developed recurrent disease with shorter DFS as compared to patients with “front-positive” tumors. This was also observed in the subgroup analysis for the control group, and with a similar trend in the short-course RT group. No such appearance was seen in the long-course RT group, possibly due to the smaller number of cases available for this assessment. In some of the long-course RT cases, few tumor glands were left after treatment, and for this reason, no evident invasive front could be detected. However, despite this evident difference in DFS between the patients with “front-positive” and “front-negative” tumors, these two groups had practically identical DSS, which, due to the differences in the year of diagnoses between these two groups, could reflect the improvements in the treatment of recurrent rectal cancer.

The staining pattern of CD44v6 lost its significance in multivariate analysis. As in a number of other studies[34], we also found infiltrating tumor growth pattern to suggest an adverse DFS and a tendency towards a shorter DSS. The close correlation of CD44v6 staining pattern with this prognostic factor may at least partly explain the lack of CD44v6 as an independent prognostic factor in our study. In addition, the other functions of this protein, such as binding of growth factors[35], may subvert the advantage of “front-positive” tumors.

Taken together, we found that tumors with “front-negative” CD44v6 membranous staining pattern were strongly related to invasive behavior. Our results substantiate the hypothesis that the lack, rather than overexpression, of membranous CD44v6 in the invasive tumor front contributes to rectal cancer progression. Although associated with a shorter DFS in univariate analysis, “front-negative” phenotype did not prove to be an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis, possibly confounded by other prognostic factors, including tumor growth pattern. We propose that analyzing the intratumoral staining pattern of membranous CD44v6 could offer a simple tool to predict the patients at increased risk for disease recurrence and thus in need of more aggressive postoperative treatment approaches and close monitoring.

We are grateful to Mrs. Sinikka Kollanus for her skilful help in laboratory work and Mr. Jaakko Liippo for aid with the digital pictures.

Colorectal cancer is a common malignancy. Radiotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy has been used to lower the risk of local recurrence. Still, a significant proportion of patients comes down with disease recurrence that is challenging to treat and causes harmful symptoms. New prognostic markers are constantly being studied to identify better the patients who need more aggressive treatment approaches in addition to surgery. CD44 variant 6 (CD44v6), a cell membrane receptor binding extracellular components, has been demonstrated to associate with rectal cancer progression and prognosis, but with discrepant results.

In many studies, CD44v6 has been suggested to play a role in tumor progression and metastasis. The important area in the work was to study whether there is a difference in rectal cancer prognosis according to the intratumoral staining pattern of CD44v6. In contrast to previous studies, authors also included patients treated with radiotherapy before surgery.

The previous studies on the percentage and intensity of CD44v6 expression in rectal cancer have not been conclusive with regard to prognosis, because the overexpression of this protein has been associated with both favorable and adverse survival. Although alteration of CD44v6 expression in tumor invasive front has been demonstrated, its association with rectal cancer prognosis has not been studied in detail. Interestingly, the authors found that the patients with tumors showing CD44v6 expression in the invasive front presented with a longer disease-free survival time than did the patients whose tumors expressed protein more centrally. Moreover, the latter “front-negative” type was associated with infiltrating tumor growth and narrow tumor-free margin, both known to be adverse prognostic factors. Instead, the authors did not find the percentage and intensity of CD44v6 staining to be related to disease prognosis. The authors concluded that for rectal cancer progression and prognosis, more important than the actual amount of CD44v6 might be its distribution within the tumor.

The study suggests that patients with “front-negative” rectal cancer may need more aggressive treatment and monitoring after surgery.

Prognostic factor is a situation or a condition, or a characteristic of a patient, that can be used to estimate the chance to recover from a disease or the risk for the disease recurring. Invasive front is the interface of tumor and host tissue; the deepest rim of cancerous tissue grown in adjacent non-cancerous tissues.

In this work, the authors investigated the prognostic value of CD44v6 in patients treated with/without preoperative radiotherapy. The results are interesting and suggest that the lack of membranous CD44v6 in the rectal cancer invasive front could be used as a method to identify patients at increased risk for recurrent disease. The article is generally well written.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Cem Onal, Department of Radiation Oncology, Baskent University Faculty of Medicine, Adana Research and Treatment Center, 01120 Adana, Turkey

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11836] [Article Influence: 845.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Improved survival with preoperative radiotherapy in resectable rectal cancer. Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:980-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 1818] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huerta S. Rectal cancer and importance of chemoradiation in the treatment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;685:124-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lesley J, Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with extracellular matrix. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:271-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 771] [Cited by in RCA: 796] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Herrlich P, Morrison H, Sleeman J, Orian-Rousseau V, König H, Weg-Remers S, Ponta H. CD44 acts both as a growth- and invasiveness-promoting molecule and as a tumor-suppressing cofactor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;910:106-118; discussion 118-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ponta H, Sherman L, Herrlich PA. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:33-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Günthert U, Hofmann M, Rudy W, Reber S, Zöller M, Haussmann I, Matzku S, Wenzel A, Ponta H, Herrlich P. A new variant of glycoprotein CD44 confers metastatic potential to rat carcinoma cells. Cell. 1991;65:13-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1193] [Cited by in RCA: 1237] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zlobec I, Günthert U, Tornillo L, Iezzi G, Baumhoer D, Terracciano L, Lugli A. Systematic assessment of the prognostic impact of membranous CD44v6 protein expression in colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2009;55:564-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Heider KH, Hofmann M, Hors E, van den Berg F, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Pals ST. A human homologue of the rat metastasis-associated variant of CD44 is expressed in colorectal carcinomas and adenomatous polyps. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:227-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wielenga VJ, Heider KH, Offerhaus GJ, Adolf GR, van den Berg FM, Ponta H, Herrlich P, Pals ST. Expression of CD44 variant proteins in human colorectal cancer is related to tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4754-4756. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Mulder JW, Kruyt PM, Sewnath M, Oosting J, Seldenrijk CA, Weidema WF, Offerhaus GJ, Pals ST. Colorectal cancer prognosis and expression of exon-v6-containing CD44 proteins. Lancet. 1994;344:1470-1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Coppola D, Hyacinthe M, Fu L, Cantor AB, Karl R, Marcet J, Cooper DL, Nicosia SV, Cooper HS. CD44V6 expression in human colorectal carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:627-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nanashima A, Yamaguchi H, Sawai T, Yasutake T, Tsuji T, Jibiki M, Yamaguchi E, Nakagoe T, Ayabe H. Expression of adhesion molecules in hepatic metastases of colorectal carcinoma: relationship to primary tumours and prognosis after hepatic resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:1004-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Morrin M, Delaney PV. CD44v6 is not relevant in colorectal tumour progression. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bendardaf R, Lamlum H, Ristamäki R, Pyrhönen S. CD44 variant 6 expression predicts response to treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2004;11:41-45. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mulder JW, Kruyt PM, Sewnath M, Seldenrijk CA, Weidema WF, Pals ST, Offerhaus GJ. Difference in expression of CD44 splice variants between proximal and distal adenocarcinoma of the large bowel. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1468-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Peng JJ, Cai SJ, Lu HF, Cai GX, Lian P, Guan ZQ, Wang MH, Xu Y. Predicting prognosis of rectal cancer patients with total mesorectal excision using molecular markers. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3009-3015. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Peng J, Lu JJ, Zhu J, Xu Y, Lu H, Lian P, Cai G, Cai S. Prediction of treatment outcome by CD44v6 after total mesorectal excision in locally advanced rectal cancer. Cancer J. 2008;14:54-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhu J, Xu Y, Gu W, Peng J, Cai G, Cai G, Sun W, Shen W, Cai S, Zhang Z. Adjuvant therapy for T3N0 rectal cancer in the total mesorectal excision era- identification of the high risk patients. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zlobec I, Lugli A. Invasive front of colorectal cancer: dynamic interface of pro-/anti-tumor factors. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5898-5906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Sobin LH, Wittekind C, editors . TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 6th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss 2002; 72-77. |

| 22. | Glimelius B, Påhlman L, Cervantes A. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v82-v86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jass JR, Atkin WS, Cuzick J, Bussey HJ, Morson BC, Northover JM, Todd IP. The grading of rectal cancer: historical perspectives and a multivariate analysis of 447 cases. Histopathology. 1986;10:437-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Korkeila E, Talvinen K, Jaakkola PM, Minn H, Syrjänen K, Sundström J, Pyrhönen S. Expression of carbonic anhydrase IX suggests poor outcome in rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:874-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hart IR, Goode NT, Wilson RE. Molecular aspects of the metastatic cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;989:65-84. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Faleiro-Rodrigues C, Lopes C. E-cadherin, CD44 and CD44v6 in squamous intraepithelial lesions and invasive carcinomas of the uterine cervix: an immunohistochemical study. Pathobiology. 2004;71:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nagtegaal ID, Marijnen CA, Kranenbarg EK, Mulder-Stapel A, Hermans J, van de Velde CJ, van Krieken JH. Short-term preoperative radiotherapy interferes with the determination of pathological parameters in rectal cancer. J Pathol. 2002;197:20-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Naor D, Nedvetzki S, Golan I, Melnik L, Faitelson Y. CD44 in cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2002;39:527-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gosens MJ, van Kempen LC, van de Velde CJ, van Krieken JH, Nagtegaal ID. Loss of membranous Ep-CAM in budding colorectal carcinoma cells. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:221-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Suzuki H, Masuda N, Shimura T, Araki K, Kobayashi T, Tsutsumi S, Asao T, Kuwano H. Nuclear beta-catenin expression at the invasive front and in the vessels predicts liver metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1821-1830. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Ishida T. Immunohistochemical expression of the CD44 variant 6 in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2000;30:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mueller BM, Schraufstatter IU, Goncharova V, Povaliy T, DiScipio R, Khaldoyanidi SK. Hyaluronan inhibits postchemotherapy tumor regrowth in a colon carcinoma xenograft model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3024-3032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sleeman J, Moll J, Sherman L, Dall P, Pals ST, Ponta H, Herrlich P. The role of CD44 splice variants in human metastatic cancer. Ciba Found Symp. 1995;189:142-151; discussion 151-156, 174-176. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Jass JR, Love SB, Northover JM. A new prognostic classification of rectal cancer. Lancet. 1987;1:1303-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ponta H, Wainwright D, Herrlich P. The CD44 protein family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |